Case 23. Continuous Process Reforms to Achieve a Hybrid Supply Chain Strategy: Focusing on the Organization in Ricoh

† Kyoto Sangyo University, Kita-ku, Kyoto, Kyoto, Japan; [email protected]

Introduction

Are reforms of business processes in a supply chain (henceforth, supply chain processes) time limited or continuous? Global companies in advanced nations that are exposed to rapidly changing conditions in both their domestic and international markets should adopt an approach for introducing continuous reforms to the supply chain. These global companies must develop supply chain processes that can simultaneously achieve two strategic targets—operational efficiency and responsiveness—to continue to mine mature domestic markets and to open up overseas markets in advanced and emerging countries. Achieving both these targets usually requires a considerable period of time.

A hybrid strategy synthesizing a lean strategy to target efficiency and an agile strategy to target responsiveness has been called lean/agility or “leagile.” Because the strategy was proposed by Naylor et al. (1999), a body of theoretical and empirical study has been accumulated (Mason-Jones et al., 2000; Naim and Gosling, 2011; Qi et al., 2009; Stavrulaki and Davis, 2010). However, there has hardly been any discussion regarding what kind of organizations are best suited to this hybrid strategy. Continuous reforms in supply chain processes are essential if this challenging hybrid strategy is to be realized. What role, then, should be played by the organizations that conduct these continuous process reforms?

This case study considers Ricoh Company, Ltd. (henceforth, Ricoh), a leading Japanese company with a global presence that created a hybrid supply chain strategy for its office imaging equipment, such as copiers and printers. Ricoh has been conducting process reforms for over 10 years, resulting in a supply chain that is highly efficient and responsive. To advance these process reforms, Ricoh established a cross-functional committee to investigate and conduct reform projects and a supply chain management (SCM) promotion department to support these reform activities. In this case study, we introduce the activities undertaken by the committee and the SCM promotion department to achieve Ricoh’s process reforms. With the help of this case study, the author endeavors to stimulate a debate among readers regarding why continuous process reforms are required and what organizational elements are required to make them successful.

Company Background

Ricoh manufactures and sells office imaging equipment, mainly copiers, printers, multifunctional printers, projectors, and facsimile machines. It also provides services and business solutions for these appliances. It divides its global market into the following five regions: Japan, the United States, Europe, China, and Asia Pacific. Its supervisory headquarters are in Tokyo, New Jersey, London, Shanghai, and Singapore. It provides sales and services to over 200 countries and regions worldwide, with 14 manufacturing plants in Japan and 7 overseas. In fiscal 2011, Ricoh achieved consolidated sales of 1.9 trillion yen (approximately 23.8 billion USD), and at the end of March 2012, it had 109,241 employees on a consolidated basis.

Process Reforms

The foundation of Ricoh’s process reforms is a response to customers’ diversified needs through a reduction in product life cycles in the second half of the 1990s that followed the shift toward digitization and networks for office imaging equipment. Previously, products would have a life cycle of two to three years; however, after Windows and the Internet became established as the de facto standards for information technology, Ricoh reduced its typical product life to slightly more than a year. Because of this change, Ricoh could no longer hold onto its surplus inventory and had a growing need to develop a supply chain that could respond rapidly to diverse customer needs at a low cost.

At the end of the 1990s, Ricoh introduced business process reforms and an integrated information system, which it used to launch reform projects aiming to achieve low-cost operations, while simultaneously increasing the levels of customer satisfaction. In the second half of 1998, Ricoh began a trial of a method that it termed “plant kitting” for its laser printer, one of its main products. Prior to this, Ricoh manufactured the main body of the various types of printers and the optional parts at its plants and these were then stored individually in sales company warehouses. Following an order from a customer, the person in charge of the sale would pull the required parts out of inventory and send them to the customer’s office, where the product would be assembled and installed. Even orders that involved implementing memory boards and/or network boards, or customized tasks such as setting up an IP address, were conducted by the salesperson responsible for the order.

In contrast, plant kitting entailed a series of operations that were all conducted at the plant. First, based on the details of the order acquired from the sales company, the main body of the printer and the optional parts were manufactured separately. Next, based on the confirmed order information, the product was assembled rapidly and customized at the plant. Finally, the completed product, which was assembled according to the customer’s specifications, was delivered directly to the customer. In other words, Ricoh was aiming to achieve a lean/agile hybrid strategy for its printers.

This trial reform was implemented in conjunction with several other process reforms. In 1999, Ricoh began a trial change to weekly production instead of the conventional monthly production at its plants within Japan. At the start of the trial, Ricoh established production plans for two-week periods. In 2003, Ricoh formally adopted this process using a weekly production plan, and Ricoh’s plants in America and Europe also changed to weekly production.

On the product development side, in 1999, Ricoh began moving toward modularization, and in 2003, the company began to use the Modular Build & Replenishment (MB&R) production method. Under this method, modules (the core parts common to all products) are manufactured at Ricoh’s consolidated production bases in Japan and China and subsequently shipped to the appropriate international production bases where the product will ultimately be used. The product is then assembled to completion based on the final specifications.

On the procurement side, in 2000, Ricoh introduced the “RaVender-Net” network infrastructure in which transactions with suppliers are conducted using electronic data interchange (EDI) to digitize quotations, drawings, orders, and other documents. In addition, Ricoh provided support for process reforms at the plants belonging to its suppliers in order to increase the accuracy of deliveries for weekly production units. On the sales side, in 2003, Ricoh’s sales planning department in Japan began producing sales plans on a weekly basis. In 2005, Ricoh created a system for a weekly sales-production plan in which sales and production were linked on a per-week basis. The company subsequently expanded this approach beyond printers to its other core businesses, and in 2005, it launched plant kitting for its medium-sized multifunctional printers. In 2008, Ricoh started production based on orders for its large-sized multifunctional printers.

In conjunction with these process reforms, Ricoh also introduced a number of integrated information systems. In 1999, it introduced the Daily Production-Sales-Inventory Monitor (DPSIM), which displays data about items such as production and sales planning and results, production status, and inventory information in daily units. In 2002, it introduced Global Inventory Viewer (GIV), which displays data regarding inventory conditions, and in 2003, it introduced Production-Sales-Inventory Automation Planning System (PSIAPS), which supports sales planning.

As a result of the implementation of the reform projects described above, Ricoh’s percentage of total sales from overseas grew from approximately 40% in fiscal 1999 to about 50% in fiscal 2012, whereas the percentage of total overseas production increased substantially from approximately 50% to approximately 90%. Amid the significant changes taking place in Ricoh’s production and logistics networks, its inventory turnover period declined from the typical 2.6 months to less than 2 months. At the same time, it reduced the time required to deliver and install a customer’s order to one-quarter of the time taken previously. It is noteworthy that Ricoh’s inventory turnover period on a monthly basis has trended at a level significantly lower than that of its competitors. These results verify that Ricoh has been able to achieve both low-cost operations and increased customer satisfaction through the development of a hybrid supply chain.

Organizational Operations

The SCM group established in April 1999 was responsible for promoting this series of reform projects. The mission of this department was (1) to make business processes visible and to conduct operational reforms, (2) to make progress in companywide structural reforms by determining the framework for companywide SCM activities and promoting these activities, and (3) to optimize companywide supply chain activities through the development of a supply chain based on the customer’s perspective.

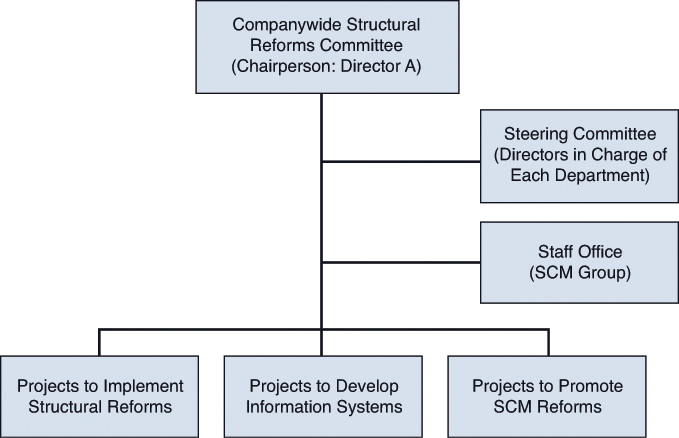

After the fundamental concept for the reforms and a plan for their implementation were created within the SCM group, the Company-Wide Structural Reforms Committee (henceforth, the reforms committee) was established in February 2001. As shown in Exhibit 23-1, three types of projects were established under the reforms committee umbrella: projects to implement structural reforms (henceforth, structural reform projects), projects to develop information systems, and projects to promote SCM reforms.

Director A, who had overall responsibility for the SCM group, was appointed chairperson of the reforms committee, and the SCM group filled the staff office role. Structural reform projects were established for each department: production, product development, domestic sales, overseas sales, and services. The director in charge of each department was given the overall responsibility for the reform, whereas the department head or section head served as the chairperson of the committee for that reform. In addition, a steering committee comprising the directors in charge of each department was established. The purpose of this was to give them the opportunity to deepen their understanding of the reforms being conducted at work sites, acquire an awareness of the issues, make informed decisions, and provide advice in order to develop the members of the steering committee as general managers. Ricoh was able to create this sort of companywide structure for promoting reforms owing to the strong leadership of Director A, who was the chairperson of the reforms committee.

The reform projects progressed in the following manner. In order to coordinate the reform themes, the chairpersons of the reform project committees would meet with the chairperson of the reforms committee and a representative of the staff office at the start of the fiscal year. After the reforms themes were decided upon, the members of each reform project committee would implement the reforms. The reforms committee met every month and received reports and issues presented by two or three of the reform project committees. It would share this information with, and listen to, the opinions of the members of the steering committee and the members of other project committees. In addition, in some cases, it would request the cooperation of other departments, which would subsequently be reflected in the reforms. Director A (chairperson of the reforms committee) and the SCM group (the staff office) held regular meetings twice per month to coordinate the direction to be taken with the reforms and to share information on any issues encountered. Further, Director A and the SCM group met with the president of Ricoh once per month to report on the progress of the reforms. Both of these regular meetings were also attended by the chairpersons of the main reform project committees. When required, these chairpersons would answer questions and coordinate with members of other project committees.

Ricoh also established SCM reforms committees in four regions of operation outside of Japan. Under the guidance of the regional sales headquarters, these committees have incorporated production departments into the reform efforts and they continue to conduct reform activities to this day. An SCM general meeting was held in Japan once per year between 2001 and 2009 so that these overseas committees could coordinate and share information on their progress and the issues that they encountered with the reforms committee. Moreover, Director A and members of the SCM group visited each of the four other regions twice per year to check on the progress that had been made and to provide guidance and support.

In addition to functioning as the staff office for the reforms committee, the SCM group fulfilled the following two roles. First, it advanced cross-departmental reform projects that were difficult to categorize in each department (production and sales process reforms and logistics process reforms). Second, it advanced reforms to monitor and achieve the targets set for the two key performance indicators (KPI) of inventory and logistics cost. Specifically, it would request performance data from the relevant departments, compile all the data, prepare presentation materials, and distribute these materials to the relevant departments and top management. In addition, if performance had deteriorated, the SCM group would request a report from the relevant department outlining the causes and suggesting how to resolve these problems. On some occasions, members of the SCM group were dispatched to the relevant department to provide support. In these ways, the SCM group played an extensive role, thoroughly monitoring the progress of both cross-departmental process reforms and those being conducted by individual departments.

Suspension and Restarting of Committee Activities

The reforms committee met almost every month, for a total of 86 meetings in the 9 years from its establishment up to November 2010. However, upon the retirement of Director A, it was determined that the reform projects had reached completion, and thus the activities of the reforms committee were suspended. Nonetheless, owing to the effects of the Great East Japan Earthquake that occurred approximately half a year later in March 2011, the flooding in Thailand in the fall of the same year, and the financial crisis in Europe, Ricoh’s inventory became imbalanced, with shortages of some of its best-selling products and excess inventory of products that did not sell as well. To address the changes in its operating environment, Ricoh developed an emergency supply process to deal with the problem of product shortages, to minimize inventory imbalances, and to make full use of the supply chain system that it had previously developed, including such elements as postponement, inventory visualization, and direct deliveries to customers. Despite these efforts, Ricoh was unable to stabilize its level of inventory performance, and as a result, it recorded an operating loss in the fiscal year ending in March 2012. This result demonstrated to Ricoh that it had to improve its SCM system further.

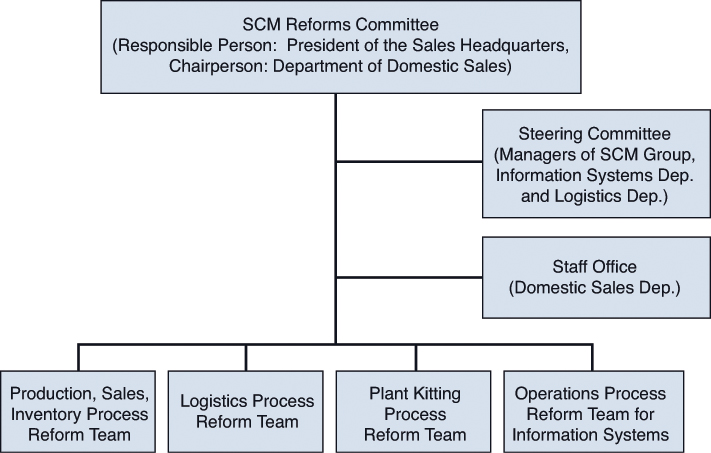

In August 2012, Ricoh established a new SCM reforms committee in Japan, influenced by the SCM group. As shown in Exhibit 23-2, the president of the sales headquarters was given overall responsibility for this committee, while the staff office was established within the sales headquarters. The same organizational structure used by the overseas SCM reforms committees was adopted in Japan. Four reform teams were established under the control of this committee: the production, sales, and inventory process reform team; the logistics process reform team; the plant kitting process reform team; and the operations reform team for information systems.

As the SCM group no longer functioned as the staff office for the SCM reforms committee, its members were incorporated into the various reform teams and became involved in the planning and implementation of the projects. Some of these members also became members of the steering committee and participated in committee decision making. Moreover, in order to continue to implement and progress companywide SCM reform projects, a team was established within the SCM group that was responsible for documenting, as intellectual assets, the expertise that Ricoh had acquired thus far by implementing its process reforms. Consequently, the SCM group became responsible for not only supporting the progress of process reforms and thoroughly monitoring them but also implementing reforms and creating intellectual assets from the expertise that Ricoh had acquired.

Discussion Questions

1. After Ricoh suspended its companywide structural reforms committee, the performance of its inventory worsened due to the effects of the Great East Japan Earthquake, the floods in Thailand, and the financial crisis in Europe. It has subsequently been unable to stabilize the level of its inventory performance. Can you speculate on the connection between its suspension of a cross-functional committee and the instability of its inventory performance?

2. What do you think about the organizational elements necessary to implement continuous supply chain process reforms?

References

Mason-Jones, R., Naylor, B. and Towill, D.R. (2000), “Lean, agile or leagile? Matching your supply chain to the marketplace,” International Journal of Production. Research, Vol.38, No.17, pp.4061–4070.

Naim, M.M. and Gosling, J. (2011), “On leanness, agility and leagile supply chains,” International Journal of Production Economics, Vol.131, pp.342–354.

Naylor, J.B., Naim, M.M. and Berry, D. (1999), “Leagility: Integrating the lean and agile manufacturing paradigms in the total supply chain,” International Journal of Production Economics, Vol.62, pp.107–118.

Qi, Y., Boyer, K.K. and Zhao, X. (2009), “Supply chain strategy, product characteristics, and performance impact: Evidence from Chinese manufacturers,” Decision Sciences, Vol.40, No.4, pp.667–695.

Stavrulaki, E. and Davis, M. (2010), “Aligning products with supply chain processes and strategy,” International Journal of Logistics Management, Vol.21, No.1, pp.127–151.