2. Global Population Growth and Migration

For centuries, scholars have studied the stories of the past to predict what will happen in the future. Our story begins in the very distant past—400 million years ago, to be exact. In a sparsely populated area that would later encompass the United States’ upper Great Plains region and Canada’s southernmost provinces, a massive petroleum deposit formed within and beneath a 15,000-square-mile shale bed.

Advancing to the 1950s, the most significant petroleum deposit ever unearthed in North America was discovered on the property of North Dakota grain farmer Henry Bakken. Back then, Williston, North Dakota, was fairly unknown outside the plains and was not the center of any major industrial activity. In 1953 Stanolind Oil and Gas first drilled into what is now called the Bakken Formation. Modern-day geologists believe its reserves contain over 4 billion barrels of oil and natural gas—enough to meet current worldwide demand for over a decade. Despite half a century’s worth of drilling, though, many ignored the region’s significance because of preconceived notions about domestic petroleum development.

Typically, wealthy nations satisfy their large-scale demands for petroleum by importing it from the resource-rich (albeit underdeveloped) states surrounding the Persian Gulf, Niger Delta, and Caspian Sea rather than establishing or increasing domestic production. Importing is rooted in simple economics. It’s just cheaper to extract petroleum resources from soft, sandy ground in distant regions and pay transportation fees than to extract from the concrete-like rock layers dominating local areas like the Bakken region. For the longest time, scientists, engineers, and oil companies were uncertain that drilling in shale fields would even yield quantities large enough to justify local production. The extensive damage that would occur to pricy drilling equipment was a virtual certainty.

But out of necessity arises innovation, and in the late 2000s, America saw just that from its petroleum industry. At the time, crude oil prices were skyrocketing across the world due to depleted supply and the Middle East’s political tensions. At approximately the same time, new technological advances for hydraulically fracturing, or “fracking,” rock formations were being devised, along with other techniques that enabled diagonal and horizontal drilling. This perfect storm of technology finally provided viable access to hardened shale formations, and though expensive, it rendered equipment costs bearable.

Only then did social, technological, and economic forces converge to make the Bakken region attractive to producers—and ripe for development. Seemingly overnight, the Bakken Formation became a de facto source for U.S. producers, representing a surprisingly lower-risk substitute for the politically unstable OPEC nations’ crude. All of a sudden, petroleum-rich geological sites like Williston were no longer blips on the radar. Between late 2007 and early 2008, producers rushed people, equipment, trucks, and technology to towns in North Dakota, Montana, and even the Canadian province of Saskatchewan to take advantage of the first true oil and gas boom since the west Texas wildcatter days a century before. Local populations exploded, and overnight the quaint little northern towns isolated by hundreds of miles of plains became bustling hubs of activity for drilling personnel and their families.

Humans have a habit of moving around to pursue resources, and local populations can rapidly grow or shrink as they do so. The Roman Empire expanded outward from modern Northern Italy to acquire more food grain, just as 19th century U.S. explorers went west of the Rockies to search for gold. Searching for new employment and better lives, immigrants from Spain and France, and later the Netherlands, Britain, and Mexico, have come to the United States to pursue the American Dream. Though earlier historical migrations were often natural responses to slavery, oppression, or religious persecution, humans in modern times tend to move en masse to acquire new resources. The key difference between the past and present, however, is that large-scale migrations used to take place over many years or decades. This allowed local infrastructure changes to evolve naturally and methodically, according to the exodus or influx of people. For instance, accompanying the Gold Rush’s westward expansion was the transcontinental railroad, which workers in Utah finished only a few years following peak gold extraction.

Mass population movement creates a temporary, but meaningful, imbalance between the local demand for goods and their local supply. With forty-niners arriving in California faster than its settlements were prepared to accommodate, shelter, cattle, equipment, and service shortages were problematic early on. To alleviate the maladies and inconveniences that such imbalances create, systems that balance supply with newly derived demand must be extended to the new location of interest, or invented wholesale. When large-scale migrations occurred in the past, people found a way to develop the infrastructure for providing supplies, whether they did so by bringing the groundwork with them or creating it along the way. As the Romans slowly moved northward into what now are Switzerland and Germany, they assembled complex supply lines along self-built roads to provide food, water, horses, and weapons to their newly conquered territories. When the native Germanic tribes learned their military technology was no match for the advancing Roman forces, they resorted to attacking their enemies’ supply lines to level the playing field. The plan worked. The Romans were starved, and their headway slowed. Such is the importance of supply infrastructure in a new or booming population center.

Though ancient, the Roman example holds truth today by illustrating how important a seamless supply chain is to organizational success. Modern and future populations depend on local supply chain ecosystems that are carefully designed to address forecasted supply and demand ranges for citizens to thrive or survive. The designed systems need to be flexible and agile to support the dynamic demand patterns that are characteristic of migratory locations. If they aren’t, profits and businesses may face the same fate as the early Roman conquerors.

Additionally, though its supply chain implications are substantial, large-scale migration is not the only source of population growth concern that future supply chain practitioners need to prepare for. In technologically modernizing places like China, Brazil, India, and Africa, the consumer population is simply growing organically—and rapidly, at that. Medical care, food and water quality, and lifestyle advances are causing developing nations’ populations to flourish at both ends of the human life cycle. Whereas one in three infants in a nation like Nigeria was historically unlikely to reach his or her tenth birthday, infant mortality in traditionally underdeveloped areas is rapidly ebbing. At the age continuum’s opposite pole, people in both underdeveloped and developed nations alike are living longer. They are surviving cancer, eating healthier, and extending their lives through vitamin intake, education, exercise, and better eldercare. The result of these forces in combination is the large, serious population growth—either organic or via migration—that the world has witnessed over the past several decades.

Although lengthened human lifespans are in many ways encouraging, because they indicate social progress, the leveling of health indices across major world regions comes at a consequential economic cost. Population growth is straining various economic systems. Workers must produce more to support an increasingly large number of nonworkers (the young and old). Relatively equal production volumes must be more efficiently allocated across geographies. Finally, when combined with underdeveloped nations’ recent per-capita wealth increases, population growth is creating new markets that are increasing goods and services that supply chain managers are charged with making available.

This chapter looks at how both organic and migration-induced population growth will affect future supply chains. The basic premise is simple: Demand can shift much more rapidly than supply chain managers can adjust to the changes that are occurring, and the imbalances caused will yield severe cost and service considerations for businesses. Additionally, population changes lead to other social phenomena that will exacerbate these imbalances, such as resource scarcity, deterioration of the physical environment, demand decentralization, and the natural geopolitical strains that are linked to each of these issues. This chapter explores population change, with an eye on these potential opportunities and threats. We provide some initial directions for supply chain managers to consider when taking future action in response.

Impacts of Population Change on Demand and Supply

Much of the Bakken extraction activity since 2007 has taken place within a highly concentrated 300-mile-wide circle with Cartwright, North Dakota, at its center. The hamlet is only a few miles from Montana and a couple hours’ drive from the Canadian border. The 2000 U.S. Census cataloged the entire region’s population at about 50,000 people. Supply and demand were relatively balanced, and the local economy was stable, based primarily on grain agriculture. But we’re confident that no one could have predicted what would happen next.

When populations grow and move, some economists have noted that these changes present socially tenuous challenges for global and local societies. The Bakken Formation’s newfound importance yielded an influx of workers and their families to the area, swelling the population by an estimated 200%, which unleashed migration-related chaos. While the Great Recession of 2008–2011 brought about severe worldwide unemployment challenges, Bakken officials describe an inversely dire situation. Currently there are roughly nine jobs per applicant, and employers are inviting people to move to the area by promising lucrative paychecks and lifestyles. Though the region may have vast stores of natural resources, it doesn’t do the world any good if there isn’t enough manual labor available to develop and commercialize them.

In Richland County, Montana, mounting traffic clogs the few existing roads connecting fire stations, schools, and grocery stores around the clock. Vacant hotel rooms are long gone, leased on annual contracts rather than nightly ones. Tent cities are popping up in farm fields that are no longer harvested because their farmers make a better living driving supply trucks and selling silo space to be filled with fracking sand. The high-paying oil field jobs have also depleted the local labor pool. Finding new schoolteachers—the supply of which elsewhere often exceeds 150% of classroom need—has become nearly impossible. Fast-food restaurants such as Taco Barn offer signing and retention bonuses for hourly workers. Crime in Sidney, a neighboring town, has exploded. Because the government cannot allocate additional resources to its police force, and because there are no people to fill these jobs anyway, the residents carry guns, much like in the Old West. County officials have expressed a need for new cellular towers and electricity substations, but other, more critical issues supersede them. Interviews with transient workers reveal even more pressing issues involving the availability of fresh drinking water, proper washrooms, adequate food supply, and shelter suitable for harsh northern winters.

The problems caused by population shifts are both very real and difficult to predict. Yet most businesses and governments fail to plan for such scenarios, instead burying themselves in periodic issues that reflect their stakeholders’ more immediate needs. Had Richland County been better prepared, would workers be sleeping in tents on the prairie? Perhaps. Or would innovative companies and governments already be profiting from the newfound opportunities that have presented themselves? This question is worth asking: How could contingency planning principles borrowed from other scenarios have impacted the area and business as a whole in a more positive way? For instance, a public-private partnership between local or federal government and industry could be formed that would temporarily facilitate the transportation of goods and equipment to rapidly industrializing areas. This would be much like how the Federal Emergency Management Agency transports food and temporary housing to locations hit by natural disaster. Not all disruptions to the supply chain are negative. One form of supply chain risk is that something positive will occur to an area or institution, but the key stakeholders are unprepared to take advantage of it. Unleashing the power of forecasting, demand planning, and inventory management—all key supply chain functions—on a rapidly growing area may yield greatly positive impacts on both industry and the area as a whole. This is but one key example of how better coordination of goods and material flows might not only bolster the citizens living in an area afflicted by risk, but also would provide great opportunity for the profit-seeking organizations working within it.

When areas grow in population, scarcity of commodities like fossil fuels and drinking water, as well as scarcity of services such as farm labor, may present serious supply chain dilemmas for the foreseeable future. We address this problem later in the book. To better comprehend what causes scarcity, it is important to understand first how and why populations change and why such changes are confusing. The following section presents two competing population growth perspectives that are diffusing through modern political and media systems. The ultimate goal is to define guidelines for future supply chain managers to follow when situations like those facing North Dakota and Montana arise. But first we must explain our logic for why population growth presents both threat and opportunity for the supply chains of the future.

Population Growth Perspectives

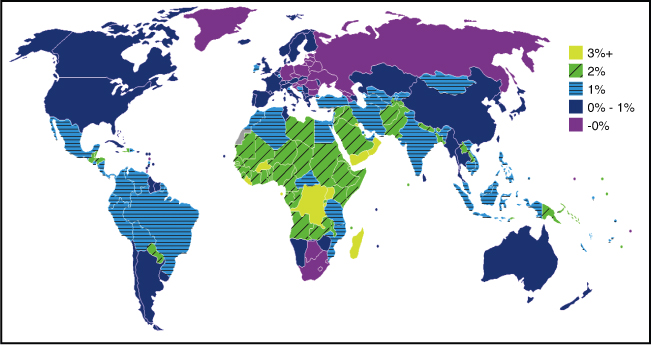

The Earth’s population has been exploding for the better part of the past century. The planet currently is home to just over 7 billion people, a massive number that stands in stark contrast to the 2 billion Earthlings at the end of the Great Depression. This is still far more than the 3.5 billion people who were around when man first landed on the moon. Not only are we all mingling with the largest number of people ever to occupy the planet, but the annual population growth rate is also increasing faster than ever before. Figure 2.1 illustrates how the world population has grown (and may continue to grow), and Figure 2.2 identifies the places where it has been growing the fastest. Based on data compiled by the U.S. Census Bureau and the United Nations, Figure 2.1 charts world population by decade beginning in 1928. It took many millennia for the Earth to reach the baseline of 2 billion people, but if the current population growth trends continue, it will take only another century to more than quadruple that number. By 2050, less than 40 years from now, the world could be home to an astonishing 9.5 billion people if growth rates don’t change.

Figure 2.1. World population growth and projections1

1 Historical and projected world populations (1950–2050) drawn from U.S. Census Bureau estimations. www.census.gov/population/international/data/idb/worldpopgraph.php. Populations from 1930–1940 provided by a 2006 United Nations report. www.un.org/esa/population/publications/sixbillion/sixbilpart1.pdf.

Figure 2.2. Population growth rate by country

Future population growth predictions such as these tend to be where the disputes manifest, and two general schools of thought are prevalent. The first traces its roots to Thomas Malthus, an 18th century English philosopher and religious figure. In 1798, Malthus wrote his famous Essay on the Principle of Population, a work that was among the first to publicize potential negative impacts that a growing populace could have on global resources and citizens. Adherents to the classical Malthusian school believe that the Earth is endowed with a finite and definable supply of natural resources. They also believe that the human population’s plausibly infinite growth will eventually deplete these resources unless we take active measures to either slow birthrates or increase death rates. This view holds that populations should increase over the long term because any emerging human innovations will increase the population, thus satisfying a basic need for survival of the species. This view also holds that innovations won’t advance the standard of living of the few via greater human productivity (satisfying an advanced social need for the few). Classic Malthusians generally agree that in pursuit of familial self-interests, the population will continue to grow until the Earth’s resources are insufficient to sustain life.

The historical situation on Easter Island is a classic illustration of Malthusian theory. Several hundred years ago, Polynesians settled the formerly unpopulated island and immediately set about cutting down trees to make boats and tools. When European explorers found Easter Island some time later, they noted the island’s large population. Roughly 200 years after that discovery, returning explorers were stunned to find that the natives had deforested the island, effectively depriving themselves of their primary food and shelter sources and forcing them to abandon their homeland. They estimated that the population had decreased by nearly 80%. Malthus’s central argument—that populations will eventually outpace and devour their available resources—has been demonstrated across multiple historical scenarios, not just Easter Island. However, adherents are not entirely pessimistic, because they also agree that it is indeed possible to break out of the “Malthusian trap” via radical innovation. They believe the human race will continue to grow until a critical resource, such as oxygen, potable water, or food, is catastrophically exhausted. At that point the human race should be capable of innovating a solution that will ensure their survival by reducing the absent resource’s harmful effects.

Stanford University biology professors Paul and Anne Ehrlich might be classical Malthusianism’s contemporary high priest and priestess. In 1968, the Ehrlichs wrote The Population Bomb, a book intended to spark worldwide dialog related to the problems they believed would result from Earth’s overpopulation. According to the Ehrlichs’ research, the Earth has a “finite carrying capacity” for inhabitants. Based on their contemporary data, they predicted a large, nonlinear increase in human population would overload the planet’s biological and geological ecosystems before the turn of the 21st century. To avoid the forthcoming Malthusian trap, they proposed a basic, albeit controversial, solution: Earth’s population must be quickly stabilized or reduced, preferably by decreasing birthrates through contraceptive education. (The Ehrlichs admitted that increased death rates, based on disease, war, and famine, would lead to an equally effective outcome.) Furthermore, if we failed to alter our birth and/or death rates, the Ehrlichs argued, the alteration would eventually happen involuntarily. This is because massive food and water shortages, severe ozone depletion, and political conflicts over increasingly scarce resources would occur. These factors would combine to form an uninhabitable planet by the late 20th century.

Though the “population bomb” didn’t explode at its expected magnitude, its predictions were not entirely without merit. In a recently published revision, the authors reconciled their initial predictions with modern history. They noted that, as they had predicted, humans did innovate: Birthrates have indeed slowed due to contraception innovation, but only in the world’s more industrialized nations. In agreement with the Ehrlichs’ primary thesis, national populations’ age distributions have widened as medical innovations have prolonged human lives. Oceans are overfished, metal and mineral stores are being diminished, alternative food sources aren’t developing fast enough, and many world regions have dangerously low food and freshwater availability.

In underdeveloped nations, things have proceeded much as the Ehrlichs originally predicted, because these are the last areas to gain access to technological advances usually required to stave off self-destruction. Of the top ten population growth rates, all are occurring in nations below the median world gross domestic product (GDP). The rapid population expansion of the Third World has stemmed from the availability of neonatal medicine, malaria-controlling mosquito nets, HIV and AIDS treatments in sub-Saharan Africa, and greater access to emergency medicine. Yet hunger and starvation plague nearly half the world’s nations. Nearly a third of the global population, which resides almost entirely in poorer nations, has insufficient drinking water, and this number is expected to rise.

Even in wealthier nations like the United States, where food and water are plentiful, people can feel the effects. Demand for products designed for senior citizens, such as eldercare and golf courses, is surging and reflects overall growth at the upper end of the age spectrum. More effective cancer treatments and greater knowledge of the cardio system are extending their lives. But cities are getting more crowded and traffic more congested, creating longer commutes, polluted urban vistas, and more aggregate crime. Bordering U.S. states like California and Arizona, as well as Georgia and Tennessee, have clashed over freshwater rights or are expected to. Another foreboding sign is prophetic commodity speculators such as T. Boone Pickens anticipating future price spikes by buying up water rights in rural and suburban areas. What does this mean for the developed world? In short, there are more of us, we are living longer, and although population growth is tempering, we are all demanding goods and services at an unprecedented rate.

The Ehrlichs do admit in their recent rejoinder that their original theory was incorrect or shortsighted in many ways. Currently we can state with certainty that there remains enough supply of most goods and services to sustain the world population for a while longer, and overcrowding has not had the disastrous effects on the planet that were predicted. The discrepancies from the Ehrlichs’ original projections are twofold. Population growth shows signs of slowing worldwide. And although the current demand-satisfying supplies are distributed very inefficiently around the globe, they do tend to eventually become available when a true resource crisis emerges.2

2 This has ensured that the classical Malthusian philosophy remains a tenet of “politically moderate” environmentalists. In some cases, however, the original Malthusian theory has been twisted to serve political purposes that are disingenuous to the original theory’s postulates. A modern-day offshoot known as NeoMalthusianism purports that negative environmental impact is a result of population size, affluence level, and technological efficiency. According to the Neo-Malthusians, population growth is bad for society simply because they increase negative environmental impacts with a multiplier effect. Similarly, affluence is seen as bad because it proportionally increases consumption, and technological efficiency is bad because it enables mass consumption more than it diminishes birthrates. Because people seek both affluence and technology progress, Neo-Malthusians see each additional person in the populace as a threat to the environment, a disease spreader, a resource exhauster, and a potential war starter. Limited empirical evidence supports their key premises; thus, Neo-Malthusians have actually damaged the Classical Malthusians’ cause. Population impact skeptics can point to them as radical reformers detached from the “realities” of growth. Unfortunately, by taking a similar position a bit too far, the Neo-Malthusians have made it convenient for casual observers and detractors to lump the two together.

Because empirical evidence supporting these weaknesses is available, an alternative school of thought, known as the Cornucopian philosophy, has developed. Cornucopian ecologists believe that the Earth possesses infinite resources for human purposes. In the rare occasions when we truly run out of something, we immediately innovate to find more supply or create a viable substitute. To Cornucopians, innovation will increase exponentially forever, such that population growth’s disadvantages will never overtake innovation’s benefits. The Cornucopian logic adheres to the following sequence:

• As nations progress through developmental life cycles, they initially consume as many resources as needed to survive, disregarding consequences.

• As they consume resources beyond a critical point, their civilizations modernize and become highly productive.

• At a certain point, highly productive societies become innovative and self-actualized, eventually becoming efficient.

• As efficient societies use fewer resources to meet end goals, they encourage others to do the same, thus creating an endless cycle of innovation and resource protection.

Chief Cornucopian economist Julian Simon argued the following in The Ultimate Resource, a more modernized response to The Population Bomb:

Because we can expect future generations to be richer than we are, no matter what we do about resources, asking us to refrain from using resources now so that future generations can have them later is like asking the poor to make gifts to the rich.

Obviously, this implies a view diametrically opposed to that of the Malthusians, suggesting that innovation is expanding exponentially and infinitely. Agreeing with the Cornucopian philosophy means believing that each successive innovation will be better than its predecessor, and that we humans will find infinite numbers of ways to use the Earth’s resources to meet our needs.

We wrote this book about future supply chains. Nobody really knows if humanity will develop (and retain) the innovative capabilities required to solve the multitudinous problems we will create for ourselves. Therefore, we believe it best to adopt a moderate position on the Neo-Malthusian/Cornucopian continuum for the purposes of this book. From a pragmatic standpoint, it makes little sense for us to embrace either end of the spectrum. Doing so would imply that the next 25 years’ innovations are unknowable or that we’ll all be dead by then anyway, rendering our position (and this book) irrelevant. But empirical reasons also support our adopted perspective. The Neo-Malthusian view becomes untenable when hard data indicates that innovation does take place in response to population growth problems, such as the birth control pill and the current experimental successes with seawater desalination. Similarly, the Cornucopian view wilts when we consider that hunger and disease are indeed major world problems and that many critical commodities (oil, zinc, copper) are increasing in price far beyond and much earlier than the expectations of years past. Factual evidence supports the notion that population growth is slowing into a classical Malthusian equilibrium, with some innovations supplanting demand, and others lagging behind. Adopting one extreme view or the other in this ideological debate would distract us from the more pressing issues we are advocating. Thus, the neutral, classical Malthusian position we take in this book ensures that we remove as much bias as possible from our advice to tomorrow’s managers and allows us to play the percentages as well.

Organic Population Growth Issues for Supply Chain Managers

Seven billion people can consume an enormous amount of resources, but modern managers can reengineer their supply chains to balance disparity among us. More people put pressure on global supply chains because supply and demand shifts introduce imbalance into the networks in place. Take China as an example of impending supply chain instability. Whereas China has long been a net exporter, the country’s increasing population growth and developing production economy have shaken the world economy since the late 2000s. This confluence of forces is generating a sizable Chinese consumer class as factory managers, accountants, teachers, and the like have started consuming much like their Western counterparts.

As shown in Figure 2.3, rapid changes in demand location based on population shifts have great potential to disrupt even the most well-thought-out supply chains. In the figure, a Western company has established a supply chain network designed to serve customers in North America and Europe, based on supply bases constructed there and in Brazil. If, as predicted, demand shifts to the locations indicated by the ovals (where organic growth is occurring most rapidly), the company faces difficulty in adjusting in the short term. Even small consumption increases in highly populated nations like China and India can create enormous strains on global supply chain processes. The population growth projections for Western Europe, Canada, and the United States for consumers ages 15 to 60 allow us to calculate that slightly less than 600 million people there will be primed for goods and services consumption in 2010–2015. This same consumer category is estimated at over 2.5 billion people in Southeast and Eastern Asia by 2015.3 Even if we assume that only half the new citizens there would have Westernesque buying power, that would mean that the Asian markets would have more than twice the market potential of Western markets. As an example of the potential impact, you can imagine the impact that this sort of growth would have on goods manufactured in Asia intended for insertion into Western companies’ supply chains. When transportation costs and higher fuel prices are factored into the equation, will it be more economical for manufacturers like Acer and Sony to divert supply to Asian consumers rather than ship overseas to smaller but wealthier markets? Managers can only speculate, but the playing field is changing in ways that Westerners could hardly have imagined 20 years ago. These types of changes will wreak havoc on contemporary demand management functions and make supply chain network design a nightmare for many companies in the coming decades.

3 Voeller, John C. (June 2010). “The Era of Insufficient Plenty,” Mechanical Engineering Magazine.

Figure 2.3. Hypothetical demand-supply misalignment

Additionally, a number of underdeveloped nations sustaining significant growth are also home to untapped deposits of natural resources. The United States Central Intelligence Agency has long known of the vast resource stores—and political strife—that exist in the Central African Republic. As is typical during disputed government transitions, the country has seen a number of conflicts resulting in lawlessness and violence throughout its regions.4 Such political instability makes it difficult for global organizations to take advantage of the Central African Republic’s vast natural resources pool. The U.S. Department of State reports that untapped resources include gold, uranium, and possibly even oil,5 yet diamonds are the only mineral the country is truly exploiting. And the Central African Republic isn’t the only country with yet-to-be-tapped natural resources. Nearby Zimbabwe, which mines both metallic and non-metallic ores, is still recovering from hyperinflation and government instability,6 but it also possesses enormous resource stores. Niger, too, has only recently started exploiting its natural resources, and it may see future industrial significance—if it can manage to develop vast coal and oil deposits.7

4 The World Factbook: Central African Republic. (2011). Central Intelligence Agency.

5 Bureau of African Affairs. “US Relations with Central African Republic,” U.S. Department of State, 24 July 2012.

6 The World Factbook: Zimbabwe. (2011). Central Intelligence Agency.

7 The World Factbook: Niger. (2011). Central Intelligence Agency.

Present-focused companies and their managers will need to develop more robust supply chain networks that can support these emerging, value-generating consumer and supply markets. Several different areas of supply chain thought will be affected. In terms of supply chain strategy, the question of whether to be agile and customer-focused or lean and efficiency-focused will become more difficult to answer. Given perpetually adjusting supply-and-demand centers, you can easily envision a scenario in which a trend toward supply chain agility will begin to trump the current “efficiency” mantra. Any additional costs will be passed along to customers or redacted from supplier accounts and contracts. Managing physical demand uncertainty comes at a cost, and many (but not all) customers will be willing to pay it. An outgrowth of this strategic decision process may be the innovation of supply chain “flexworks.” These are rapidly morphing networks that consist of publicly or privately shared manufacturing facilities, warehouses, and carriers whose purposes change in real time in response to shifts in demand patterns. Flexworks are similar to the information networks used by modern cellular communications companies to distribute data packets. When a call is placed, then and only then does the intelligent network decide how best to route it. Similarly, when a customer order for grapes, tree mulch, or power tools is placed in the future, will each shipment be picked, packed, and routed based on the assets available for use in real time? If so, two consecutive, identical orders placed by the same customer might be filled via two wholly different supply chain systems, each maximizing profit for the entire system on an order-by-order basis. These are but a few of the ideas that future managers should consider when optimizing the supply chain of the near future based on population trends.

Supply Chain Problems Created by Migration-Based Growth

Though organic population growth is problematic for companies and supply chain managers, rote increases in numbers of people tend to be predictable in the short-to-medium term and often can be addressed with careful demand planning, as described at the end of this chapter. On the other hand, we believe that migration issues will present even greater challenges.

For thousands of years, people have trekked across the Earth to meet various objectives. The planet’s earliest inhabitants engaged in nomadic behavior as the most natural way to satisfy their basic needs, searching for food and lands having a habitable climate. As societies evolved and organized, migration became a way to avoid war, persecution, natural disaster, social displacement, or even slavery. Yet modern migration patterns don’t truly reflect the globalization hype we often hear of in news reports related to immigration, internationalization of trade, and cross-border commerce. In his World 3.0 treatise, Pankaj Ghemawat sifted through hard industrial data from many sources. He found that only less than 3% of persons migrate annually, a relatively miniscule amount considering the business media hype surrounding globalization. Still, a fraction of 7 billion people is still a lot of migrators. This means that in 2011–2012, nearly 210 million people packed their bags and moved to another country. By mid-century, experts predict this number will be closer to 500 million.

Why are Earth’s citizens so interested in moving around? Population ecologists agree that in modern times, most people migrate to pursue economic opportunity. Labor is now the primary motivator, because modern society views remittance as more important than permanent residency. As a simple example, busloads of people leave Seattle each week to work a 14-day shift in the Bakken region before returning home to spend their paychecks and then return later. As another example, each year thousands of Mexican nationals cross the border (legally or illegally) to earn U.S. dollars to send back to their homeland.

As supply chain management professionals, we should be concerned with how migration will upset local supply-and-demand balance and increase companies’ costs, especially as global supply chains meet broader, faster migration. Whereas in the past people developed social identities with strong ties to their homeland, many children of today were born—or have become—“global citizens,” ready to move almost anywhere if the opportunity is right. Naturally, this means we take our demand for coffee, toffee, swimwear, and software with us. It isn’t that unusual to hear of a child born in India, raised in England, educated in the U.S., and employed in China before being transferred to Canada, where he or she starts a family. Present and future companies will have to react decisively to massive numbers of people moving from city to city and nation to nation to remain sustainable. This issue will be challenging, given modern supply chain networks’ semipermanent structures built around medium-to-long-term agreements involving multiple companies, and relatively fixed assets such as warehouse buildings, roads, mines, fields, and production plants.

Two particular manifestations of modern migration could create significant mayhem for future supply chains and their managers. First, when populations migrate, their demographic subgroups often do not migrate in relative proportion. What this means for modern businesses is that both product assortments and their volumes change simultaneously in new and former locations, further compounding the complexity of demand forecasting. The Bakken region provides particularly telling evidence supporting this claim. When hundreds of people moved to western North Dakota, most of them were men, a phenomenon characteristic of oil field jobs. One of the region’s grocery suppliers reported a spike in men’s hygiene product orders, whereas female cosmetics did not have similar purchase increases. Issues such as these make supply chain functions like procurement (where contracts are often negotiated based on overall volume discounts) difficult for supply managers to address. In such cases, flexible contracts combined with the aforementioned flexworks might stave off the inevitable stockouts that arise from poor forecasting or demand sensing. Of course, this implies that the risks inherent in traditional supply chain management will be spread or shifted somewhat socialistically. Companies will be challenged to put the performance of the entire system ahead of short-term goals—a difficult recipe, to say the least.

Given that the Bakken migration took place in a country with a well-developed transportation and logistics infrastructure, we can expect that within months, supply chain managers will adjust to the supply/demand imbalance in toiletry goods by diverting inventory from other warehouses and recalibrating transportation. (However, if many companies do this simultaneously, we will see traffic jams like those in Williston.) As people from across the world continue to migrate in search of resources and better opportunities, we see much larger problems arising. For example, a sizable chunk of the Chinese migrant worker population still lives in the nation’s rural inland. As opportunities arise along the coast, though, more and more able-bodied workers head east to pursue more lucrative careers. The result has been telling. In just a few years, the advent of a burgeoning middle class has clogged the nation’s internal infrastructure, sent its property prices skyrocketing, and choked the environment with smog and other pollutants. This is the price of migration, especially when societies’ other businesses, public infrastructure, and natural ecosystems cannot keep up.

This leads us to a second, and perhaps more daunting, trend noted by sociologists and economic geographers: humans’ movement from rural areas into cities, a phenomenon known as urbanization. Numerous researchers have commented on the trend toward migration to large cities, a practice that has accelerated over the past decade. The McKinsey Global Institute conducted a study in 2012 that found that approximately one billion new consumers will emerge by 2025. Of these, roughly 60% will live in one of the 440 cities on Earth that can be classified as “emerging” in terms of their size and consumption. These cities are expected to deliver about half of the total GDP growth (which should be about $20 trillion) at that time.8 Figure 2.4 shows World Bank predictions that by 2030, over 80% of the world’s population will live in urban areas versus the 50% populating them today. The worldwide 50% mark was achieved for the first time in 2011.

8 McKenzie Global Institute. (2012). “Urban World: Cities and the Rise of the Consuming Class,” white paper.

Figure 2.4. Percentage of the world’s population living in urban areas

Why are populations urbanizing? There are many explanations for why people migrate, but sociologists have narrowed the roots of rural-to-urban migration to three primary forces: rural flight, quality-of-life issues, and economic opportunity. To put these more colloquially, people are moving to cities (or creating new ones) because the role of humans in world agricultural efforts is diminishing in the new knowledge economy; because cities provide more interesting and valuable opportunities for needs fulfillment; and because, at a fundamental level, that’s where the jobs of the present and future are and will be. Of course, as a result, our concern is that global supply chains are not currently designed to be conducive to matching demand and supply in the urban environment due to traffic congestion, pollution, and customer service challenges. Most major U.S. cities’ transportation infrastructures are already congested, even without taking into account the increased demands of urbanization. We address this subject in greater depth in later chapters, but it’s worth considering that as of 2010, over 20 major U.S. airports exceeded their cargo capacity—and no major airport construction has been planned to increase capacity.

The key questions are scary for current managers to consider. First, how do we service intensified concentrations of people within a geographic space when, as a result of this intensification, very little (or very expensive) space remains to store products? When designing the networks of the future in urbanized areas, conventional center-of-gravity models with intermediately positioned distribution centers won’t suffice. Companies and industries need to investigate new urban-centric models of storage, scheduling, lot sizing, and customization. Related to this, the costs of real estate inside congested areas will skyrocket, but locating outside the congestion will result in unattainable delivery windows and missed or delayed shipments. Not to mention, the sheer cost of retail space will render current store designs obsolete due to their excessive space for stock. Additionally, in the most congested urban areas, such as London and Paris, many logistics delivery vehicles and inventory storage sites are prohibited by law from entering or passing through, making access much more difficult. How will these challenges be met and managed?

The Future Supply Chain Manager’s Population-Oriented Agenda

Balancing supply and demand is the biggest challenge for world-class supply chain managers. However, in the face of changing populations, the time will come when addressing these issues with long-term planning will become a pipe dream. In the short term, adjustments can and should be made to SKU-level forecasts for key items. Investing in synchronizing supply chain management technology may reduce the costs of poor forecasting. For items with longer customer or supplier lead times, the sheer volume and sporadic nature of population changes is a potential hazard that will create great inefficiency for businesses. We see the following specific effects as the most damaging to the firm’s supply chain management effort (and, therefore, they present the greatest opportunity for savvy managers):

• A shortage of supply in the optimal locations to satisfy extremely large-scale demand

• Different approaches to public investment in infrastructure across similarly crowded areas

• Difficulty in assessing where rapidly changing demand will come from

• Increased assortment due to population diversification within restricted geographic spaces (geographic demand heterogeneity)

• Shortage of advantageously located real estate and transportation assets to serve increasingly crowded areas

• Shortages of energy and water for use in conversion processes unless new sources are located and tapped

• Shortages of adequate retail store and stock space in crowded areas

• Insufficient port and airport capacity, creating expensive bottlenecks

• Problems with the accuracy of demand forecasting models for many products as customers live longer, use products differently, and consume earlier or later in life than ever before

Issues related specifically to increased consumerism and resource scarcity are addressed in greater detail in forthcoming chapters. For now, we will discuss how to prepare for the specific challenges associated with organic and migratory growth. Managers first need to narrow their focus to the potential effects that population growth and migration will have on the eight critical processes from the Global Supply Chain Forum framework. Table 2.1 lists each process and describes the potential adjustments that may be needed to address population growth, migration, and demographic change.

Table 2.1. Population Growth and Migration Implications on SCM

Population growth and migration present several distinct challenges to the process of customer relationship management. You might think that the greatest future challenges will rest with retailers and businesses that sell directly to consumers. We suggest that although these organizations will most certainly find themselves on the front lines of changing population dynamics, the reverberations will be felt throughout the supply chain to the point of raw-material extraction. Each organization’s CRM process will reflect changes in customer tastes, volumes, and locations. These customers will bring not only distinctive tastes, but also their perspectives on how business should be conducted. This will require companies to be adaptive in the CRM process to negotiate terms that stray from convention.

Leading companies will also increasingly employ CRM software and powerful analytics to wade through the complexity of customer data. Although CRM software is primarily used today among retailers as they sort through consumer purchasing data, it will find increasing application in business-to-business settings, helping to illuminate trends, buyer tendencies, and market opportunities with distinct segments and individual customers. Firms operating in globally diverse markets and/or with widely assorted product lines will find it hard to do without.

In addition, companies’ customer service management process will experience some of the greatest challenges with respect to addressing the macrotrend of population shifts. As the company’s “face to the customer,” this process will be forced to adapt to ever-increasing diversity of tastes, preferences, biases, and sensitivities. This translates into limitations on efficiency within company-customer interfaces. For instance, how many different languages must customer service personnel be prepared to accommodate? Beyond recognizing customer issues, how prepared are service representatives to address the problems? Although customer service expectations currently vary around the world, it seems probable that these will greatly homogenize and/or settle at the highest level of customer accommodation, which of course will become the global standard. Once excellent service is rendered in one company interaction in a particular setting, customers quickly become accustomed to heightened standards. It is unlikely that, in the globalized marketplace, many will be willing to settle for less.

Before they address customer service process issues, companies will experience growing pains as they try to better understand diverse customers and their expectations. What does a crisis look like for a given customer? What might be considered routine for one customer could be a major crisis for another. Supply chain executives will have to sort through the expectations, establish variable but appropriate service standards, and spell them out in the product-service agreements established with customers. This could present many challenges due to culture clashes and general lack of understanding from market to market. The leading supply chain companies will have boots on the ground in all key market venues, establishing systems to become prepared before full-scale penetration occurs.

Furthermore, forecasting changing consumer tastes as well as anticipating the quantities and locations of demand will prove challenging to companies that are fortunate to sell goods and services in emergent markets. More intensive sharing of sales data and promotional strategies among companies in the supply chain will feed complex forecasting models based on artificial intelligence/neural network platforms. These expert systems will incorporate the best of quantitative, data-driven techniques and blend the insights of managers and executives who closely watch the business.

Although firms must continue to seek improved forecasting techniques, companies gearing up for the future are also encouraged to devise more collaborative and flexible supply chains that reduce the dependence on forecasts. That is, more response-based systems will be devised in an effort to flex with the market dynamics. Supply chain initiatives like vendor-managed inventory (VMI) and collaborative planning, forecasting, and replenishment (CPFR) that put supply chain partners “on the same page” when it comes to fulfillment planning will gain great popularity. Yet beyond responding to changing demand, companies will employ more persuasive tactics to shape demand. By deploying tactics similar to Dell’s “sell what you have” approach, companies will employ dynamic pricing and promotional strategies. This will direct customers toward products for which supply is great and away from items approaching stockout. Therefore, the options available to a customer at one point in time will likely change based on the supplier’s ability to fill the order. Furthermore, as we have mentioned, the route the product will take from the plant to the end user depends on the supply chain assets most available at the time of order.

The manufacturing flow management and order fulfillment processes will face perhaps the greatest change of all the supply chain processes with the “population” macrotrend. Conventional practice in producing and distributing goods involves significant capital expenditures (CAPEX), with expectation of leveraging facilities for 20 or more years. Shifts in demand population will seriously challenge this convention in two primary ways. First, it will be difficult to acquire and sustain operations in the central business districts of growing cities. Property values, government restrictions, and congestion will combine to discourage companies from making significant “land grabs” in the cities. Rather, the downtowns will be regarded as safe havens for residential, office, and retail activity. Industrial activities like production and distribution will be relegated to the metropolitan periphery. Second, companies will be reluctant to assume mortgages on properties when the market landscape is changing in dramatic fashion. Companies will continue to entertain outsourcing (though not necessarily offshoring) through contract manufacturing and third-party logistics in an effort to alleviate this fixed-cost burden and provide greater flexibility. In fact, it is likely that large logistics providers will continue to expand their footprints in the supply chain, regularly performing value-added production activities close to the market.

Therefore, supply chain network designs will assume a very different character from their current composition, which embodies size and economies of scale as the driving forces. Flexibility and market access should supersede our fixation on cost economies, though flexibility will not be achieved “at any cost.” Companies will become more open to flexworks and collaboration with outside parties—noncompetitors and competitors alike—to achieve a blend of high service and low costs. The opportunities for third parties to facilitate such collaborations on an independent, unbiased basis will be great.

The product development and commercialization process must devise the ever-growing assortment of products and services that a diverse market seeks. Gathering inputs for new products will require expanded channels of market data. Getting accurate “reads” on the market requires disparate sources. The company then must assess the market potential and determine which segments to pursue. This orientation is common today, but the level of difficulty will increase with rapidly changing demographics. Supply chain collaboration will prove essential for gathering product/service ideas and then executing a successful rollout.

The notion of centralized planning and decentralized execution in supply chain operations presents unique challenges in a hypersegmented market, where “one size fits one.” The capacity of the centralized R&D department will be critical. Those stretched too thin will struggle greatly with the rapidly growing assortment of offerings. Companies will be forced to decide whether to pursue common product platforms that can be tailored to the individual needs of the local markets or to pursue a more decentralized strategy that affords local markets the opportunity to devise wholly unique offerings. It is safe to assume that costs will be higher under the latter scenario, yet the market relevance should be greater. These determinations will likely be made on a product-by-product and market-by-market basis.

As noted earlier, some portion of goods that are sold in the market are returned to the retailers, distributors, and manufacturers. These returned goods are sometimes welcomed (in the form of reusable or recyclable content) and other times they are not, as is the case with faulty goods, misused items, or simply buyer’s remorse. Quite simply, returns are a fact of life. Supply chain managers should think about how to best accommodate their flow and generate financial return for the company. Too often, however, returns are regarded as an afterthought and a headache.

Population growth presents more than added volume to returns, but questions are associated with what qualifies as a “valid” return. Just as different cultures bring distinct expectations to the products they buy, it is possible, too, that they bring distinct expectations to the items they return. Can a well-used lawnmower be returned after a full season of use? If so, can the buyer seek a full or partial refund, a swap, or store credit? The answers are likely to vary depending on the market circumstances (the market’s general expectations) and the value of the complaining customer. Companies must come to terms with how liberal they want their returns policies to be and the uniformity with which they want to apply those policies. A more liberal returns policy can boost top-line sales but also can increase costs and challenge bottom-line profits, so finding the right balance is key.

Although this scenario speaks primarily to consumer-to-business returns, the same determinations can be found in business-to-business returns. The company must decide how best to accommodate the acceptance guidelines, credit issuance, and efficient handling of returns for its business customers. For all accepted returns (consumer and business alike), it will become more critical than ever for the company to identify why unwanted returns are occurring. Is the product truly defective, or are customers ill-informed about the product’s usage and performance? In the former case, steps should be taken to isolate the root cause of the defect and remedy the problem. In the latter case, perhaps the means by which the product is promoted and sold must be adjusted to better inform the customer. In the diverse markets of the 2020s and beyond, such opportunities for missteps are expected to increase dramatically, and a proliferation of global competition will be ready and available to pounce when failures arise.

A critical strategy for the future, then, will be to build appropriate and highly impactful relationships with supply chain partners. The implications for supplier relationship management reflect a composite of the many forces applied to the other seven business processes. Given changing demand patterns, the array of suppliers with which the company interacts is likely to increase. Measures should be taken, however, to distinguish the most critical suppliers and to seek their assistance in absorbing the risks your company faces. Risk absorption might come in the form of flexible volume arrangements, commitments to rapid ramp-up, or product take-back agreements. To attain such provisions, it is probable that longer-term commitments will be sought from these “choice” suppliers. Given the amount of effective risk transfer found in these arrangements, it will be considered a good investment.

A “team” orientation with choice suppliers will manifest not only in supporting the quality and volume needs of the focal company, but also in harvesting market intelligence that the supplier can provide and through the innovation of products and processes. Product development and commercialization can be aided by the dedication of suppliers to providing product and market insights that can drive new growth. Furthermore, it should be noted that companies that choose to outsource production and distribution activities expand the responsibility of the SRM process, with transfers occurring from “making” provisions to “buying” them. When outsourcing becomes the preferred strategy, responsibilities shift from doing the work to managing the work. As the prospects for outsourcing (again, not necessarily offshoring) increase with serving a more diverse market, the scope of SRM activity will increase in kind.

Of course, these issues represent only a portion of those that the supply chain manager of the future will face. Other issues that emerged as we discussed our findings with executives were informative because they elicited additional questions but relatively few answers. Perhaps most interesting (and, in some cases, worrisome) were the questions related to the need to sustain an adequate rural presence in the face of burgeoning urbanization. To wit, what will become of the remaining rural areas in terms of supply of necessary products and services? How will supply chain systems be designed to serve a very small number of highly critical people living in outlying areas, especially given the expected rising fuel costs of the coming years? These are among the issues we will discuss and debate as the book moves on.