5. Geopolitical and Social Systems Disruptions

Mrs. Crosby’s is a popular local cantina located in Ciudad Acuña, a Mexican village just across the U.S. border from Del Rio, Texas, and only a three-hour drive west of San Antonio. Walking into Mrs. Crosby’s is like stepping back in time. The wooden floors and furniture, antique brass and ceramic tile, and adobe walls with arched doorways (which are sometimes adorned with sombreros) create the aura of an Old West movie set. “Ma Crosby,” as the place has been known by regulars, for over 80 years attended to an enigmatic mix of local Mexican blue-collar workers, American oilmen, tourists, ranchers, and a sometimes-boisterous detachment of U.S. military officers from a nearby airbase. In fact, the café used to see so much American business, from gringos crossing the border in search of a good time, that local native and country music legend George Strait featured it in his comic cowboy ballad “Blame it on Mexico.” Strait’s lyrics described one night’s festivities there as including too much guitar music, tequila, salt, and lime, which led to the unfortunate early departure of the singer’s potential love interest. Apparently, a short trip to Mexico was to blame for the protagonist’s mischief, hangover, and subsequent aloneness.

Unfortunately, mounting numbers of Mrs. Crosby’s customers have been blaming Mexico for other, much more serious transgressions in recent years. Whereas crossing the Rio Grande in search of fiesta had been a longstanding tradition for many neighboring Texans, many now stay home in fear of the increased violence in the area stemming from drug cartel activity. Shootings, theft, and other violent crimes in recent years have discouraged potential patrons from spending their downtime south of the border. Some local Americans see the problem as a product of the Mexican government’s blatant disregard for their safety. Some patrons suggest that police “look the other way” when night falls, seemingly uninterested in quelling street violence in and around the Ciudad. More than a few regular customers from the Mexican side of the river lament that Mrs. Crosby’s now often looks more like an empty warehouse than a once-bustling and festive saloon.

It would be a gross understatement to say that the clashes between the drug cartels, law enforcement officers, and innocent bystanders along the U.S.–Mexican border have adversely impacted the local economy in recent decades. U.S. citizens working and living near the border have long sought refuge from life’s predicaments at Mrs. Crosby’s, but many no longer cross into Mexico because they fear for their lives. In the period between 2006 and 2010, drug cartel violence killed an estimated 28,000 people near the southern U.S. border.1 The problem has become extremely difficult for the Mexican and American governments to collectively manage and has in fact recently become a point of friction between the two nations during trade discussions. However, these neighboring partners are not alone in their preoccupation with drug-related trade disruption. The demand for illegal narcotics generates billions of illicit and untaxable dollars for dealer networks worldwide. According to recent United Nations estimates, drugs classified as opiates, including heroin, yield more than $65 billion of illegitimate revenue annually based on current retail prices. The cocaine market alone could be worth nearly $85 billion. Though the illegal drug supply chain extending to Texas from Latin America has operated for decades, historically it has been considered more of an inconvenience for the U.S. and Mexican governments than an international threat to commerce. But since the 1980s, crime, violence, and intimidation have slowly yielded way to economic forms of hostility.2 In spite of the apparent efficacy of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the national governments of the bordering nations seem unwilling or unable to do much to control the violence.

1 Burnett, John. (16 August 2010). “Mexico’s Drug War Hits Historic Border Cantina.” npr.org.

2 Sterling, Eric E. (1 March 2012). “The War on Drugs Hurts Businesses and Investors.” Forbes. Retrieved 27 July 2012 from www.forbes.com/sites/realspin/2012/03/01/the-war-on-drugs-hurts-businesses-and-investors/.

Pragmatically speaking, drug-related conflict certainly depresses trade along the southern U.S. border. But it also symbolizes a larger and more systemic problem affecting cross-border trade worldwide: the lack of geopolitical efficacy between many economically codependent states and nations. In the case of Ciudad Acuña, the drug wars themselves are undoubtedly important to resolve from the social and security standpoints of the locals. But they also are a microcosm of situations where businesses reliant on cross-border trade for survival are adversely affected by their national government’s inability—or unwillingness—to address larger-scale social and diplomatic tribulations. In many cases, national governments’ inactivity in solving localized societal issues inhibits the flow of goods and services between willing buyers and sellers across borders. The businesses that serve those nations as producers and consumers suffer accordingly.

To be clear, the chaos along the Rio Grande emanating from the drug trade is but one example of where a geopolitical problem—defined here as a conflict in the interests between two or more geographically distinct government entities—disturbs, interrupts, or inhibits a global supply chain from optimal performance. Generally speaking, domestic governments are not well designed to address localized commercial problems affecting businesses, especially during foreign dealings. In a way, the lack of government capability to foster micro-level economic exchange should be unsurprising. Most legislative bodies are arranged in the pursuit of multiple and sometimes countervailing objectives, only some of which are explicitly economic in nature. In the U.S., for example, the nation’s founders provided seminal guidance for administering the federal government in the form of a mandate to “promote the general welfare” of the nation’s citizens. But this mandate can be interpreted as including multiple economic and noneconomic (social or security-related) directives, and often a government’s multiple missions conflict with one another. As a result, governing bodies sometimes act to directly address one type of concern at the expense of another (which draws the ire of the latter’s strongest proponents). In modern times, this occurs most noticeably when the governing body in question seeks the advancement or preservation of social objectives, at the plausible expense of economic gains.

For example, the U.S. state of Arizona recently instituted strict—and controversial—immigration laws intended to curtail the influx of Mexican citizens moving into the state illegally. The new laws implicitly allow for the racial profiling of “Mexican-appearing” citizens and noncitizens alike during ordinary traffic stops. The result, intended or not, is that persons of Hispanic appearance can be legally intimidated, regardless of their legal citizenship status. In response, Mexico’s central government has fought stalwartly against Arizona’s new laws.3 The laws appear to be reaching their desired outcome. Surveys indicate that over 100,000 persons of Mexican descent intend to leave the state (or have done so already), with fear of persecution or mistaken deportation cited anecdotally as a leading reason. Many of those leaving the state are believed to be legal U.S. citizens.4 Some Arizona businesses are suffering economically due to the pursuit of the social objectives by the Arizona legislature, because of either a shorter supply of affordable labor or a reduced customer base.

3 Davila, Vianna. (28 June 2011). “Fear of violence hurts Acuna business.” mySanAntonio.com; “Mexico Joins Suit Against Arizona’s Immigration Law, Citing ‘Grave Concerns.’” (23 June 2010). FOX News; Reilly, Mark. (2 July 2012). “Late-night violence hurting downtown business.” Minneapolis-St. Paul Business Journal.

4 Myers, Amanda Lee. (22 June 2010). “Evidence suggests many immigrants leaving Arizona over new law.” Austin American-Statesman. Associated Press; Tyler, Jeff. (18 May 2010). “Hispanics leave AZ over immigrant law.” Marketplace (American Public Media); Stevenson, Mark. (11 November 2010). “Study: 100,000 Hispanics leave Arizona after immigration law debated.” Associated Press. MSNBC.

Sociopolitical issues such as immigration have great potential impact on firms’ ability to balance supply and demand and therefore turn a profit. For instance, on the supply side, businesses and farms across the southern U.S. have long survived—or even thrived—based on their ability to reliably attract workforces from the legal and illegal Hispanic labor pools. These workers are often willing to accept laborious positions that other demographic groups shun. However, this labor source is effectively being decimated in Arizona and a few other states that have enacted parallel legislation.5 In one notorious incident, the state of Georgia in 2011–2012 enacted laws aimed at aggressively reducing its illegal immigrant Hispanic worker population, ostensibly to “free up jobs” for American-born manual laborers. This action created a shortage of people to pick Georgia blueberries, melons, and other leading cash crops, and very few workers of any ethnicity (legal or otherwise) applied for the suddenly vacant positions. As a result, many thousands of bushels of produce died on the vine, devastating the annual supply market. Similarly, on the demand side of the equation, businesses such as restaurants, doctors’ offices, auto repair shops, and shopping malls in southern Arizona are suffering the same fate as Mrs. Crosby’s, only on the other side of the border. Though the problems associated with illegal immigration in Arizona and other border states are economically significant in terms of their influence on local demand and supply, they represent governments’ inability to address macro-political problems on a micro-level scale. Returning to the illegal drug scenario, Forbes magazine writer Eric Sterling observed recently “...drug organizations depend on corrupting border guards, customs inspectors, police, prosecutors, judges, legislators, cabinet ministers, military officers, intelligence agents, financial regulators, and presidents and prime ministers. Businesses cannot count on the integrity of government officials in such environments.”6 The lesson is that these are not simply disagreements between different groups of citizens, at or near a national borderland. They are societal systems dilemmas—related to immigration, corruption, and social neglect—between multiple national governments. There are many noteworthy instances where such problems contribute to the decline in a local or national economy.

5 Ozimek, Adam. (21 June 2011). “Georgia’s Harsh Immigration Law Costs Millions in Unharvested Crops.” The Atlantic.

6 Sterling, Eric E. (1 March 2012). “The War on Drugs Hurts Businesses and Investors.” Forbes.

The drug feuds overwhelming Mexico and the American southwest are emblematic of how toxic blends of government conflict, foreign policy, and illegal activity can harm a company or industry’s chances of survival. Mrs. Crosby’s isn’t the only business that has seen its operations interrupted because of external factors that are symbolic of greater political fissures. Problems such as terrorism, organized crime, diplomatic hostility, institutionalized corruption, and potential nationalism of foreign assets all are potential barriers to effective supply chain management when governments allow them to go unchecked or are simply unable to mitigate their risks.

The geopolitical and social systems risks we are concerned with encompass a wide and deep spectrum of activity, ranging from national government to individual levels, across high/low ranges of potential conflict and outcomes. At one end of the spectrum, we consider that large-scale conflicts between nations, such as wars and embargoes, are rare but can devastate a global supply chain when they do occur. At the opposite end, we see evidence that more constrained international issues such as cargo theft and open-seas piracy often present one-off, individualized threats that are highly disruptive to a particular shipment or situation. These threats are more easily mitigated by the involved companies via individual or government interaction. Most cargo theft involves valuable goods that can be resold on the black market.7 Following a single incident, subsequent shipments can be rerouted or additional security provided.

7 Burges, Dan. (2012). Cargo Theft, Loss Prevention, and Supply Chain Security. Waltham, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Our goal in this chapter is to unpack the most salient geopolitical and social systems issues from across the spectrum and to devote space to uncovering potential solutions to the most pressing problems facing the future supply chain manager. However, nations and governments conflict with each other daily, and in hundreds of different ways. Given our current objectives, which are centered on identifying and addressing the opportunities and threats posed to the supply chains of the future, we focus on three particular aspects of the geopolitical panorama that present the most salient conceivable supply chain impacts. First, given that we are greatly concerned with supply and supply management, we address the potential (and already realized) impacts of commodity hoarding by governments on integrated supply chain management. There is already evidence that microeconomic trade via the supply chain is being inhibited by macroeconomic policy related to scarce materials, in situations where national governments are electing to hoard or stockpile key raw materials. This topic is explored in the next section. Related to this trend, we are also concerned with the impacts that moderate-level intergovernment conflicts could have on future supply chains, in the form of export restrictions. As tensions between governments escalate, the embargo or complication of goods transfers to and from nations becomes important for companies to consider in their supply chain design. Second, given these issues, and considering them in light of the aforementioned global connectivity, we also address the potential impacts of widespread electronic network failure, particularly due to deliberate action (such as cyber attacks) on the part of governments or terrorists. The reliance of modern firms on electronic information systems presents a potentially critical weakness that must be addressed if they are to ensure supply continuity. Third, given that some critical commodities are becoming extremely scarce either locally or worldwide, we briefly consider the possibility that major military conflicts between nations and/or individual terrorism groups will inhibit both future supply and demand, and we evaluate a selection of the most probable of these scenarios. Contemplating these types of geopolitical risks provides a basis for both opportunistic advantage seeking and threat mitigation for companies in the coming years.

Commodity Hoarding and Export Restriction: The China Syndrome

The Earth is endowed with many natural resources that for all practical purposes are nonrenewable, but that are also basically “required” to sustain the human race. In addition, though some renewable resources such as grain or freshwater are relatively abundant worldwide, they sometimes exist in limited quantities in different locales. In spite of these supply restrictions, natural resources are often widely and voluminously demanded. As a result, throughout history political units have tended to organize themselves in ways that best facilitate their acquisition. Consider as a simple example that most cities in Scandinavia and Australia historically developed along coastal regions. This occurred at least in part because much of the interior land of these nations is untenable for growing crops due to weather and terrain. The indigenous peoples in each case located themselves near a reliable food supply (such as fish) and where they could most easily receive water shipment of resources brought back from abroad. However, for scarce but highly demanded resources, especially those that are nonrenewable, the “creation of availability” has often led to significant conflict between political units. Students of history can recall many instances where resource shortages have created disputes or even wars over finite but very important resource stocks. The Roman Empire conquered foreign lands to capture both servants and food supply, for example. In recent years numerous countries have warred over increasingly limited stocks of petroleum. (But often the underlying reason has been cloaked in a social cause, given that the taking of life for the sake of resource acquisition is often considered unpalatable within “civilized” society.)

When political entities such as states or nations control a preponderance of a key commodity’s supply, political tensions with others often arise. The production of oil by dictatorships, and the correlated behaviors of the OPEC countries that produce and control its supply, provide the most obvious modern example. Similarly, even as we were writing this book, one of China’s state newspapers released a report affirming that the country had begun stockpiling its reserves of several rare-earth metals needed by other nations to produce industrial machinery.8 Countries stockpile resources as a strategy to create geopolitical leverage, and this behavior both strengthens the holding nation and weakens others. For example, China accounts for an overwhelming 90% of daily world rare-earth metals production, and it holds 23% of the world’s rare-earth reserves.9 The stranglehold that the Chinese have on the rare-earth metals market insures the Chinese people against external economic threats. It also serves as a direct threat to others seeking to do business with Chinese companies or their supply chain partners. And rare-earth metals aren’t the only commodities China is stockpiling. According to an Asian coal analyst, the country had coal reserves of up to 9.5 million tons in the summer of 2012.10 Oil and coal are two of China’s main sources of energy, and for a country with such enormous domestic demand, any stockpiling is bound to affect worldwide consumption.

8 Currie, Adam. (12 July 2012). “Market Focused on Chinese REE Strategic Reserves.” RARE EARTH Investing News.

9 “China warns its rare earth reserves are declining.” (20 June 2012). BBC News: Business.

10 Bradsher, Keith. (22 June 2012). “Chinese Data Mask Depth of Slowdown, Executives Say.” New York Times.

Some economic indicators suggest that the current growth of China’s economy is slowing. If that’s the case, China may be stockpiling commodities to have near unchecked price control down the road. Therefore, scarce resources would act as a hedge against recession. If the Chinese government controls highly sought commodities, it can also regulate how much it exports at a time, thereby manipulating demand in its favor and allowing it to drive up prices in the process. Although we certainly don’t predict that these circumstances will lead to warfare in the next quarter century, they definitely put the world in a tenuous geopolitical situation. Revisiting Malthus, unless we see some sort of groundbreaking innovation that eliminates the need for these commodities, businesses and countries will be forced to buy key raw materials from the Chinese. But they won’t want—or be able—to pay monopolistic prices. The European Union, the United States, and Japan have all implicated China on such charges in recent years, but it has defended itself by claiming that the measures are necessary to adjust to falling market prices.11 Already we can see quarrels developing among countries that rely on these commodities. And, lest we appear prejudiced, it should be noted that the amassing of critical resources for geopolitical benefit is hardly confined to China. Much as China hoards palladium, tungsten, and zinc, other nations also hoard key resources and use them to barter for various national strategic considerations. Table 5.1 lists the 23 nonrenewable natural resources that are expected to become highly or extremely scarce in the next 20 years. Each of these plays a key role in producing highly demanded goods and services. The table also estimates their remaining global share by country, based on the 2012 U.S. Geological Survey.

12 U.S. Department of the Interior, Mineral Commodity Summaries, 2012.

13 Coal Statistics. (2011). The World Coal Association.

14 “Coal Matters: Global Availability of Coal.” The World Coal Association.

15 BP Statistical Review of World Energy, 2011.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

Table 5.1. Scarce Nonrenewable Resources and Known World Locations12-17

As shown in the table, numerous countries are participating in the resource arbitrage game to ensure the future safety and life quality of their people. China figures in prominently, holding the majority of the remaining quantities of cadmium, gold, and mercury. All these resources are becoming extremely rare and play a significant role in manufacturing and technological innovation processes. In addition, China holds major stockpiles of titanium, zinc, indium, and magnesium, which are needed for paints, LCDs, and thousands of metallic machine parts. Additionally, China controls over 90% of the annual production of rare-earth metals used in high-tech items such as computer monitors, communication devices, and military night-vision goggles. China has placed export controls on what the Chinese consider to be “their” mineral resources. Clearly, China will wield awesome power in terms of the future of manufacturing unless alternative deposits of many of these materials are discovered. Some scientists suspect that the ocean floors may be tapped in the pursuit of alternative sources.

Other materials, such as tellurium and tungsten, are also in drastically short supply and are also unevenly and heterogeneously deposited around the globe. Each plays a huge role in modern manufacturing processes. Many of these and other critically short resources are located inside the borders of highly unstable nations such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan. Or they are in countries that typically deal poorly with Westernized partners due to severe cultural differences or historical conflicts (Russia, Iraq, Iran, Saudi Arabia). Clearly, the advantages to a nation holding scarce and badly needed resources are many. Yet many nations holding scarce resources are also among the poorest on Earth. The U.S. Central Intelligence Agency tracks the resource positions of all the world’s nations. Several nations that are relatively low in terms of annual GDP output actually score highly on latent resource holdings. Often, this occurs because the country in question lags in the economic development cycle to such a degree that resource extraction or refinement is impossible. In some cases, the nation’s political environment is volatile enough that external partnerships for the purposes of extraction are untenable. We see such situations as presenting great opportunity for developed nations over the coming quarter century if the political barriers can be overcome.

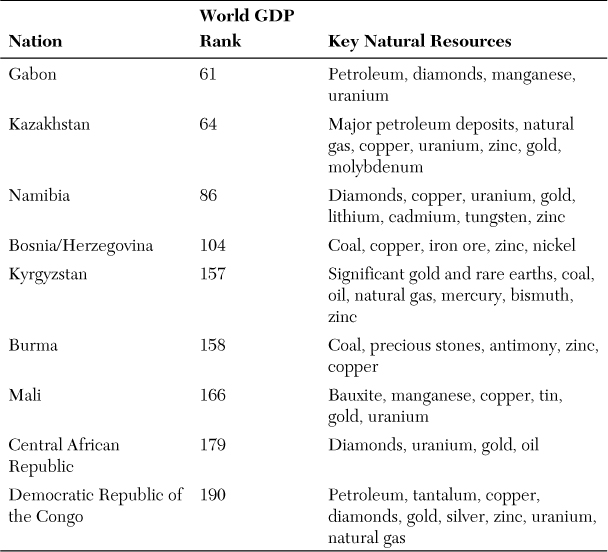

Table 5.2 highlights several such situations where the “right partnership” with an underdeveloped nation could yield surprising benefits to first-world nations or multinational enterprises. Nations such as Gabon and Kazakhstan are rapidly developing infrastructures that will allow for future partnerships to be built for such commodities as oil and natural gas. Others are less developed and currently remain hostile to outside partnerships. The CIA estimates that the Central African Republic, Mali, and Democratic Republic of the Congo possess some of the richest undeveloped resource stores on Earth, but historically they have been plagued by civil unrest and internal violence. As the world becomes more resource-strapped and economically leveled, these nations will rise in relative power if they can leverage their untapped resource bases. Firms competing in industries that rely on these resources for survival will face a serious dilemma. They can create a disruptive innovation that allows the resource in question to be eliminated from product designs. Or they can strategically partner with foreign allies (or governments themselves) that can provide sufficient access to the focal commodity.

Table 5.2. Resource-Rich But Underdeveloped Nations

Source: CIA World Factbook 2012

If the actor seeking a supply of a scarce resource is a national government, a third but more unsavory option exists: taking the needed commodity by force. However, unlike ancient times, the first resort in the modern age for acquiring scarce resources is rarely to exercise military force. Typically, today nations enter into economic agreements that are agreeable to both parties. The purchase of resources by foreign countries is a growing theme. Over $1 billion in resources currently is purchased each day via market exchanges or private transactions. However, this has made some companies in resource-rich countries fearful of foreign purchase of their raw-material resources, and this could significantly disrupt the local company’s supply chain. For example, Australia blocked the purchase of one of its ore mining companies by a Chinese firm. Australia is also currently in the middle of a controversy over the purchase of a major coal mining company by a U.S. purchaser.18

18 Wall Street Journal, August 2011; Voeller, 2010.

Alternatively, fears that national control will be surrendered are counterbalanced in many situations by export restrictions. Restrictions on exports of key raw materials can be problematic for domestic supply chains, whether or not the resources in question are renewable. Consider Argentina, one of the world’s leading corn exporters.19 Countries and companies around the world use several forms of corn to make food products, antibiotics, livestock feed, oil-based products, artificial sweeteners, and even adhesives.20 The U.S.-based Corn Refiners Association estimates that about 4,000 products in a typical American grocery store have some sort of corn ingredient. With so much depending on a single input, when a country like Argentina sets ceilings on its corn exports, the global market is bound to suffer. The Argentine government insists that it does so to “guarantee affordable local food supplies and help tame high inflation.”21 But when drought or other unforeseen disasters strike elsewhere, as they did in the United States in the summer of 2012, foreign farmers struggle to maintain production, and manufacturers must seek supply elsewhere. When “elsewhere” is a country like Argentina, which has a corn export quota of 7.5 million tons,22 the increased demand and limited supply send prices soaring. Some Argentinean farmers are pressing the government to end the export quotas so that they can increase their output.23 By way of analogy, others are circumventing the wheat ceiling by choosing to produce barley instead.24 Finding a viable substitute for corn would be useful in the same way.

19 Capehart, Thomas. (28 May 2012). “Corn Trade.” United States Department of Agriculture: Economic Research Service.

20 “Corn.” Iowa State University: Center for Crops Utilization Research.

21 Burke, Hilary and Alejandro Lifschitz. (16 July 2012). “Argentina to approve more corn exports; ‘Plant corn, boys,’ president says Monday.” Grainews: Practical production tips for the prairie farmer.

22 Walsh, Heather. (18 April 2012). “Argentina Meets About Extra Corn Export Quota, Group Says.” Bloomberg.

23 Gonzalez, Pablo. (23 July 2012). “Argentine Corn Growers Urge Export Cap to Boost Crop 60%.” Bloomberg.

24 “Argentine farmers changing from wheat to barley to avoid export taxes.” (21 July 2012). MercoPress: South Atlantic News Agency.

In summary, supply chain managers of the future will often find themselves battling the competition for not only customers, but also scarce resources. As with many supply chain tasks, the development of key relationships will be critical, especially when it appears necessary to avoid export quotas or to navigate internal conflict within a supplying nation. We expect resource hoarding to expand significantly in the next 25 to 30 years as well, as more and more resources become scarce due to increased consumption based on population growth and economic leveling. We present advice for future supply chain managers at the chapter’s conclusion.

Government Risks and Considerations

In addition to the strategic constraint of resources by governments, supply chain managers of the future will face increasing additional diplomatic and sociopolitical threats that will inhibit the effectiveness and/or efficiency of their systems. Entire books could be written about these subjects, but our research leads us to believe that three types of such future threats possess likelihood/magnitude profile characteristics that warrant consideration here. First, in many nations, the pervasive and entrenched corruption of local and national government officials has long given potential foreign market entrants pause. In many cases, government officials abuse their power in highly coordinated ways to gain personal benefit, and this endangers the long-term viability of the supply chain network in multiple ways. All nations are corrupt, just not equally so.

To judge the risks of corruption on a global supply chain venture, supply chain managers should assess both the pervasiveness and arbitrariness of the illicit activity. Arbitrariness can be thought of as the ambiguity or complexity associated with navigating the nation’s illicit social systems. For example, in India and Russia, a variety of ever-changing bribes, kickbacks, and other unethical practices are regarded by many as accepted methods for a foreign business entity to succeed. In places like Mexico and Chile, the “rules of the game” are just as pervasive but are more explicit.25 Supply chain managers should consider pervasiveness and arbitrariness together when assessing their supply chain partnering strategy in a foreign nation. As arbitrariness increases, firms may want to establish joint ventures with partners rather than locating wholly owned distribution or production facilities there or, better yet, avoid engaging supply chain partners there. As pervasiveness increases, in situations where the partner is of critical interest, the best move seems to be creating and maintaining an arm’s-length relationship, with several backup suppliers in development if possible.

25 See Rodriguez, Peter, Klaus Uhlenbruck, and Lorraine Eden, “Government Corruption and the Entry Strategies of Multinationals,” Academy of Management Review, April 2005, for a highly rigorous treatment of this subject.

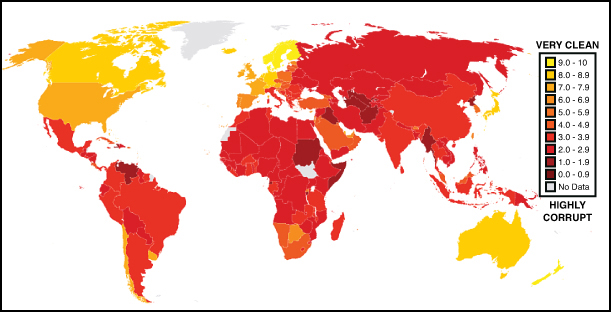

Corruption is at least to some extent an inverse function of income (in that officials in poorer nations have greater incentives to divert resources for personal gain). Therefore, managers should be aware that corrupt practices are most likely to take place when they are partnering with a resource-poor nation. The Corruption Perception Index (CPI), published annually by Transparency International, captures this phenomenon. Figure 5.1 shows a world map of its most recent CPI. The lighter shaded countries received the highest scores in the CPI, reflecting freedom from corruption. The darker shaded areas are likely to be most problematic for managers seeking to take supply or serve customers there. Notably, the least-corrupt areas according to the index include North America, Western Europe, and Australia. Areas in which to exercise extreme caution include Venezuela, Iraq, the Baltic-area former Russian states, Burma, and the areas around the eastern horn of Africa (such as Sudan and Somalia). We expect less relative corruption to occur worldwide as populations diversify and economies level; however, a number of problem spots such as these will remain threats in the future.

Figure 5.1. Corruption Perception Index, Transparency International (2011)

A second and related concern pertains to the possibility that foreign governments can either explicitly or effectively nationalize the assets of a foreign business within their borders. In many cases, domestic governments have nationalized businesses’ property without compensation to the former owners. For instance, in 1971, Libya famously nationalized the local supply chain assets of British Petroleum in response to Britain’s failure to protect it from Iranian aggression. Such situations would obviously disrupt the supply chain significantly and would cost the entrant significantly in terms of lost physical assets. In recent years, the nationalization of scarce resources such as petroleum has increased in frequency. We expect this behavior to accelerate as governments increasingly squabble over badly needed resources that are coming into short supply. Nationalizations are most likely to occur when resource prices are high (or suddenly become high), when corruption is high, when the local government is run under an extremely socialist system, and/or when that system provides for relatively weak checks and balances versus the chief government executive (president, prime minister, monarch).26 Supply chain managers should assess these issues before undertaking large and expensive market-entry maneuvers in the coming years, while adjusting carefully for the relative global scarcity of the commodity or finished good in question.

26 Guriev, Sergei, Anton Kolotilin, and Konstantin Solin. (Spring 2011). “Determinants of Nationalization in the Oil Sector.” Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization.

Third, and perhaps most important for supply chain managers to consider in the short to medium term, is the pervasiveness of uncontrolled illicit trade of counterfeit and knockoff goods in the supply-and-demand markets. The manufacture and sale of counterfeit finished goods has exploded over the past two decades. It is expected to continue in the future due to lack of customs enforcement in combination with lax intellectual property laws in many low-cost-labor nations where manufacturing occurs. In 2009, the U.S. value alone of fraudulent finished goods was over $260 million, across a wide variety of sectors, from footwear to electronics to jewelry.27 The following year the Office of U.S. Trade published a list of the primary sources of counterfeit goods in the U.S. market:

27 “Growth in Counterfeit Goods Shows No Signs of Abating.” (24 April 2010). Supply Chain Digest.

• Algeria

• Argentina

• Canada

• Chile

• China

• India

• Indonesia

• Pakistan

• Russia

• Thailand

• Venezuela

However, the report also noted that intellectual property laws were strengthening across Eastern Europe and several other world regions, indicating a glimmer of hope.

However, not all of the worries surrounding counterfeiting are centered on the U.S. finished-goods sector. Fraudulent materials are introduced at all levels of the supply chain, all around the world, every day. Counterfeit parts often are manufactured and shipped to free-trade zones worldwide for assembly into finished goods. Copyrighted intellectual products are a popular vehicle, because they represent low up-front investments for criminal enterprises. Many pirated or fake goods are currently sold online. We expect this trend to explode as criminals become more sophisticated at web design and electronic commerce and as worldwide economies flatten. High-tech and medical-device markets are another significant venue for criminal activity due to the products’ design similarity and high price points. Even the U.S. military is feeling the effects of counterfeiting. A 2012 investigation by the U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee found that over 1,800 cases of counterfeit electronic parts had been purchased and incorporated into weapons systems. We expect the trend toward counterfeiting to flourish as customers from around the world increase their participation in global commerce.

Tangible and Virtual Intentional Disruptions

It would be impractical to try to provide full coverage of the incidence of manifest physical and virtual conflict in a supply chain primer. But we believe that a few notes related to political conflict pertain significantly to our assessment of future supply chains. Some futurists and political scientists are predicting potential wars over primary resources such as water, oil, and food in the future. In the pursuit of scarce resources, conflict has occurred many times between nations and cultural units throughout history. In some cases, such conflicts take the form of traditional wars, whereby political entities literally battle over key commodities in the name of survival. As an example, the Sudan, which is divided into northern and southern regions, has long endured conflict and civil war based on its former colonization as well as its racial and religious divisions.28 Although ruling positions, elite statuses, and demographic differences are all significant in the Sudan’s complicated history, so too are the resources that the two sides have clashed over. The land is rich in natural resources—oil and water in particular. Both regions seek to establish economic and political stability, and both need control of the resource-rich areas to do so. Tribes wage civil war against one another. Neither the Sudan nor South Sudan intends to give up the fight for the borderlands that both economies need to survive—nor do they intend to compromise. The battles started in the mid-1940s, and they continue today.29

28 Raftopolous, Brian and Karin Alexander. (2006). “Peace in the Balance: The Crisis in Sudan.” Institute for Justice and Reconciliation.

29 www.upi.com/Business_News/Energy-Resources/2012/05/03/Sudans-on-brink-of-all-out-war-over-oil/UPI-16581336078729/.

We can easily envision two types of wars that have great potential for future supply chain disruption. The CIA has already noted that shortages of basic human needs—particularly food and water—are on the horizon. Given their salience to human existence, they provide significant motivation for full-scale conflicts in the future. We can particularly envision scenarios in which industrialized nations using mass quantities of water for manufacturing purposes become the targets of poorer nations needing water for human survival. Relatedly, due to the lowering of aquifers stemming from global climate change, food is becoming relatively harder to produce in mass quantities. Therefore, nations may begin to war over supplies of both food and the water needed for its irrigation in the next 20 years. Alternatively, more humans on Earth consuming more goods also equals increasingly massive amounts of waste by-products, the most significant of which is garbage. Chapter 4, “The Changing Physical Environment,” introduced the “Great Pacific Garbage Patch,” which we believe has the potential to annihilate an entire aquatic ecosystem if allowed to perpetuate. However, it is likely that many nations will come together and form agreements to police ocean dumping in the name of saving the food fish supply in the Pacific. If this occurs, and garbage volumes increase in proportion to the growing population, the potential for “garbage wars” also exists. Some futurists believe that full-scale battles will be fought over which nation is forced to serve as a region’s garbage dump. Such conflicts are already appearing in locales such as Chicago, where they are currently being fought on the battlefield of politics, rather than with guns. But there is no guarantee that less civilized and more distressed nations (with less or nothing to lose) will react similarly.30

30 Pellow, David N. (2004). Garbage Wars: The Struggle for Environmental Justice in Chicago. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

However, it is not always the case that an international conflict will take place between governments. Sometimes, small groups of actors become disconcerted with imbalances in wealth, perceive inequities in standards of living, or for other reasons seek to act violently to bring about social or economic change. In other words, though a terror act typically is executed against individuals within a society, it is often done to achieve broader political goals. Most of us are well aware of the incidences of terrorism that have received publicity since the 9/11 crisis in New York, Washington, D.C., and Pennsylvania over a decade ago. Yet we only rarely or unceremoniously consider terrorism when conducting supply chain planning. Figure 5.2 shows the terrorism incidents that have occurred since the year 2000. Not coincidentally, some of the areas we’ve been speaking of all along in the Middle East and Africa have seen the greatest occurrence rates. Logically speaking, incidences of terrorism should decrease as the planet levels into broader economic equality. However, the concern we share with future supply chain managers is that the proliferation of terrorist-enabling weapons worldwide will provide more opportunities for such criminals to act. Though the likelihood of such attacks is small, and of their success smaller, we encourage supply chain planners to consider world terror hotspots when designing future networks. We also emphasize that these may not be the same places that we all grew up dreading. When citizens of any nation become financially repressed, they eventually lash out at those who have more. As a result, it will be important in the future to consider the safety and security provided by some traditionally stable nations such as Greece and Spain, once their financial paths following the 2009–2011 recession are better determined.

Figure 5.2. Incidents of terrorism, 2000 to present

Generally speaking, if any subsequent reaction to the 9/11 attacks was productive for global supply chain managers, it was the resultant heightening of security awareness worldwide. The systems that were enacted following the tragedy to protect people have also proven to be largely effective at protecting goods and materials inventories. However, in the same time span, as we’ve mentioned, the Internet has proliferated greatly. Savvy would-be terrorists have to some degree concluded that they can do as much or more damage through cyber attacks on social, political, and financial institutions. The widespread impact of viruses, worms, and other bugs, as well as direct attacks on highly targeted institutions (through hacking) appear to be the terrorists’ next frontier. Critical systems such as power grids, intranets, dams, and credit scoring systems are all vulnerable targets and will be for the foreseeable future. Given that the supply chain trades as much or more in information and financial flows as it does physical transactions, supply chain managers should be highly cognizant of this growing threat in the coming years.

Geopolitical Challenges for Future Supply Chain Managers

Changes to the geopolitical environment will threaten the efficacy of many of the world’s increasingly globalized supply chains in the future. As supply-and-demand networks lengthen and markets diversify in location, it is possible that many different types of conflicts will present themselves as hazards to efficient and effective supply chain processes. Though a great number of geopolitical issues constantly affect world commercial activity. We see the following as key issues related to the geopolitical environment that may be particularly problematic for businesses seeking to optimize supply chains over the coming two to three decades:

• Shortages of petroleum-based fuel needed to transport goods will become common. Shipping costs and risks will therefore rise unless alternative sources are embraced, possibly leading to faux-regionalization or localization of some markets.

• Import/export restrictions on critical commodities may periodically force expensive supply chain redesigns.

• Commodity hoarding by nations seeking political advantage may shorten product life cycles and diversify supply requirements, leading to stock-keeping unit (SKU) proliferation.

• Full-blown international conflicts are possible in the next 20 years if innovation to replace some critical commodities (fuel and minerals) within high-demand product or process designs fails. Later, in 20 to 30 years, conflicts are also possible over the acquisition of basic necessities (food and water) or disposal of by-products (such as garbage and nuclear waste).

• Intentional disruption, violence, and terrorism risks will skyrocket as commodities become increasingly scarce. The effects will be proportional to the extent that local/national governments are incapable of addressing them or are willing to turn a blind eye.

• Cyber terrorists represent an equally threatening risk. They may succeed in corrupting supply chain systems that promote visibility of product and/or facilitate shopping/payment.

• Counterfeiting and black/gray markets will destroy supply chain value propositions if they are left unchecked or remain undetected.

• Regulatory risks have always existed in supply and demand market locations, but regulations of the future may be applied more aggressively and/or arbitrarily based on local perceptions of foreign businesses’ home nation. Similarly, corruption in foreign governments will always present risks to foreign supply chain assets.

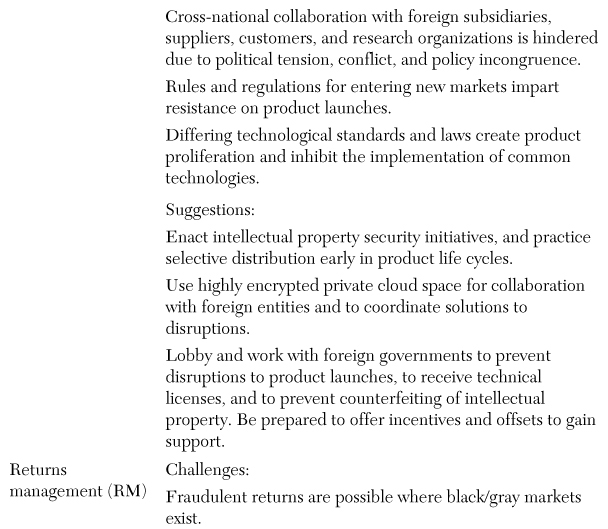

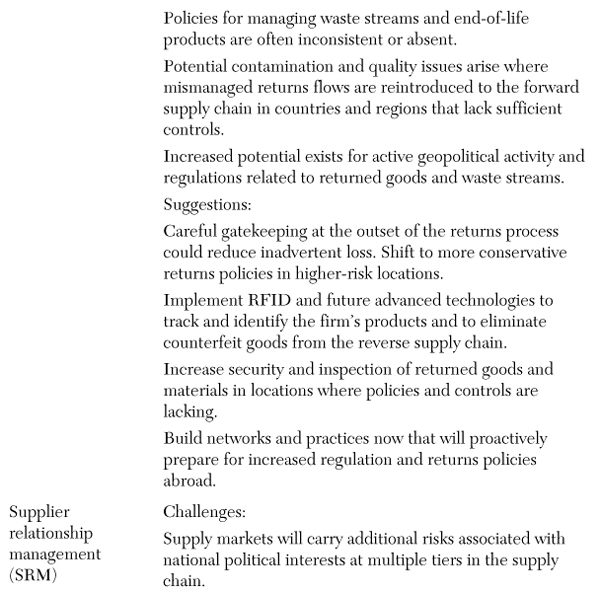

As nations develop economically, they present relatively less political risk to supply chain partners due to economic investment and inertia. We expect the economic leveling of many nations to reduce such risks substantially. However, the challenges associated with geopolitical conflict stemming from resource-based conflicts of interest are numerous and can greatly affect each of the eight GSCF supply chain processes in the future. Future supply chain managers are advised to increasingly consider geopolitical risks as potentially significant to their global supply chains and to develop contingency and/or crisis plans that address critical demand and supply points. Additionally, geopolitical risk should increasingly figure into supply chain network design, especially at more distant echelons, as new products are being developed and old ones reconfigured. Table 5.4 lists each process and describes some projected potential geopolitical change implications. As shown in the table, the implications of geopolitical risk affect each area of the GSCF and therefore influence how supply chain managers of the future should conduct business. In the area of customer relationship management, managers cannot ignore how the potential activities, policies, and restrictions created by governments will influence their business relationships with customers and supply chain partners. For example, firms must consider the geopolitical risk in the market locations they select. What seems to be an advantageous location on the surface, based on initial cost-and-profit analysis, may not be lucrative once changing geopolitical risks are included in the decision. For instance, even as recently as 2007, U.S. oil companies in the Caribbean saw their assets seized during nationalization activities of Venezuelan leader Hugo Chavez.31 Similarly, as population growth and resource scarcity increase, we expect that governments will increasingly restrict, interfere with, or even seize foreign business entities in their country. Therefore, firms should select supply chain partners who are adept at tracking and even influencing geopolitical policy and regulations in the target country where end customers are located. One way to avoid additional risk in a volatile region is to use capacity sharing agreements for transportation and production with partners who already have infrastructure in the country. Doing so avoids further investment and risk. In the future, managers must also expect geopolitical conflicts and build contingency plans for limiting the impact of potential wars, seizures, or restrictions placed on their operations. The ability to virtually extract information and pre-plan for the evacuation of resources and personnel in the event of political upheaval or war should be considered part of the cost of doing business in a transforming world.

31 Crooks, Nathan and Corina Pons. (April 2012). “Exxon gets disappointing $750 million after Venezuela seizure.” Bloomberg News.

Table 5.4. Geopolitical Change Implications for SCM

In the area of customer service management, supply chain managers need to preempt customer service failures and potential disruptions created by predictable geopolitical instability or conflict. The costs of complying with regulations or legal requirements in a host country may make it difficult to repair or replace key products or meet customer service expectations for delivery time and location. Therefore, managers should factor in the acquisition of systems and technology to establish better communication links with customers, to give them information on delays and hopefully prevent lost sales. In addition, they must work with partners to negotiate settlements, comply with customs laws, and settle legal disputes that delay effective logistics operations related to serving their customers. Establishing a customer service center in a neutral location or country to address service failures in affected nations may also help mitigate customer service problems during international political conflicts and crises. Orascom Telecommunications in Egypt did so well before the 2012 revolution. Additionally, in the future, geopolitical limits on exports and imports, as well as hording of resources by foreign entities, may lead a firm to diversify its supply sources and service locations to hedge against the effects of hoarding or political restrictions in a particular location.

For demand management, managers need to understand how geopolitical action will impact demand variability. They will have to work with supply chain partners to proactively predict and take actions to mitigate demand-related risks. As political restrictions increase in the marketplace, achieving the supply chain flexibility needed to meet demand will become more difficult. In addition, it will be important to collect information about limited transportation capabilities and network bottlenecks created by government action in the market. Firms will need to work with governments to try to reduce policies and restrictions that influence demand for their products. They also will need to work with local supply chain partners to find creative solutions to meeting demand within the regulatory environment. Strategic audits that identify avoidable risks associated with demand variability will need to be conducted. Such an analysis will help a company pinpoint areas where conducting business is too risky due to uncertainty. It also will help the company concentrate on areas where the impact of geopolitical activity can be minimized or at least managed. In the future, supply chain management may take on a much more political role. Some markets or at least market access may be entirely controlled by governments that intend to protect their own national interests and economy. Supply chain managers must be able to negotiate with governments, offer incentives, and make concessions to gain access to government-controlled markets and the lucrative demand for their products.

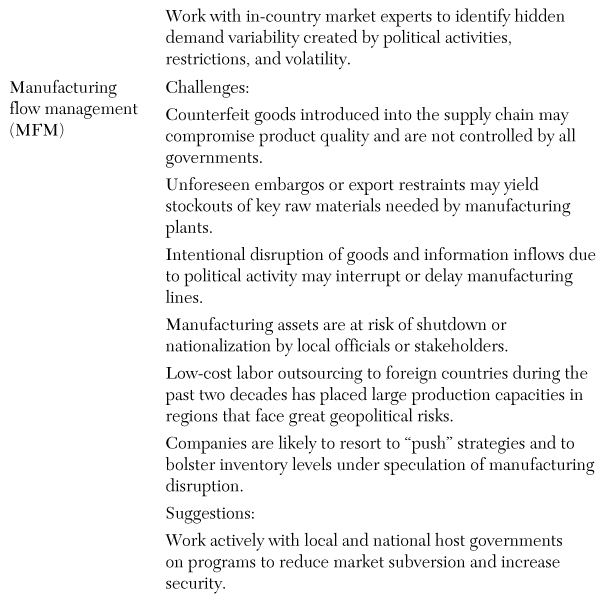

In the area of manufacturing flow management, supply chain managers need to consider and plan for possible disruptions to manufacturing capacity due to action or inaction by geopolitical actors. In particular, the last several decades have seen a major outsourcing of capacity abroad in search of lower labor costs. However, this has left a vast amount of manufacturing capacity for major global firms in areas of the world that have the potential for future geopolitical instability or disruption. Therefore, managers should consider working with host governments to reduce capacity subversion and increase security at plants. In addition, firms should consider reducing these risks by repositioning or relocating some of this capacity to more stable regions or countries. Firms should also aim to design their future networks to avoid possible geopolitical shutdowns or seizures. Finally, firms should analyze their supply base to see what risks their suppliers’ manufacturing facility locations pose to the flow of supplies to their own plants.

In future decades, managers may need to consider more radical hedging strategies that include shadow plants in nearby nations where manufacturing capacity can quickly be relocated. Or they may need to divide capacity across borders and suffer short-term cost increases to hedge against potential geopolitical disruption in lower-cost locations. Additionally, firms must embrace technology and seek to reduce manufacturing infrastructure size and cost. Doing so will minimize the risk of loss of such investments if the assets are lost due to political activity and seizure. The ability to quickly mobilize and relocate manufacturing capacity may be a measure of future supply chain flexibility. In addition, firms of the future may seek to trade more in manufacturing knowledge and information. They may limit their actual investment in manufacturing capacity and assets in the geopolitically volatile areas of a transforming world.

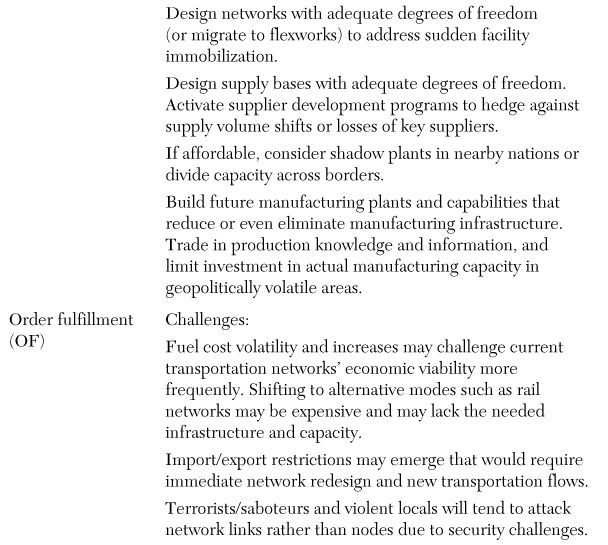

Order fulfillment in the future is expected to take place in an environment marked by increased geopolitical activity and turmoil. This will increase variability in transportation lead times, make delivery times uncertain, and increase the cost of order fulfillment. Heightened fuel price volatility is expected as nations vie for limited fossil fuel resources; increased transportation costs will be the result. Additionally, nations may employ increased import and export restrictions that limit the current ability to transport goods. Politically motivated activists and terrorists may destroy transportation lines and disrupt vulnerable in-route shipments that possess limited security. Therefore, the supply chain managers of the future must consider logistics network redesigns and product flows that limit risks and costs and reduce transportation flows in politically volatile areas. Reducing order fulfillment distances, increasing in-route security, and downshifting to slower and less costly transportation modes may be trends in the coming decades. These changes will require increased investments from public and private sources to build new infrastructures and security systems to protect product flows in a more dangerous transportation pipeline. In the future decades, firms may also need to consider more in-house security to protect product flows related to their core competencies and the execution of vital operations. Such security is already starting to be necessary for ocean vessels that traverse areas such as the Malacca Straits and Red Sea, where modern-day pirates target the flow of goods through key logistics chokepoints.32

32 Gardner, Frank. (13 March 2012). “Dangerous Waters: Running the Gauntlet of Somali Pirates.” BBC News Online.

Geopolitical actions and inactions also will make product development and commercialization more difficult in a transforming world. For example, lack of enforcement of global agreements and political tensions will make it difficult to keep new products from being counterfeited and from intellectual property from being stolen in an unstable environment. Additionally, gaining technical licenses and import approvals for new products will be more difficult in countries where political activity is aimed at protecting local markets from foreign companies and where political tension has positioned the company as being connected to a disfavored foreign regime. Such restrictions will also make it more difficult to conduct cross-border research with supply chain partners for new products and disrupt the ability to work in development teams for new-product launches. In the future, firms may be forced to practice more selective distribution of new products early in their life cycle to prevent loss of intellectual property in regions where geopolitical tension or lawlessness exists.

In addition, firms may have to be prepared to increase communications security related to new product and technology efforts. They may need to use highly encrypted private cloud space for collaboration with foreign supply chain partners and scientists to continue development efforts and to coordinate solutions within geopolitical barriers. Finally, firms may need to increase political lobbying activity with foreign governments in a future filled with geopolitical tension. Such activity will help prevent disruptions in new-product launches and prevent loss of intellectual property. However, firms may need to be prepared to offer incentives and offsets to foreign entities to gain market access and ease geopolitical tensions. For example, firms in the aircraft industry have dealt with the geopolitical difficulties of selling military aircraft to foreign countries for the last several decades. It is not uncommon for manufacturers such as Lockheed Martin, Boeing, and Northrop Grumman to offer elaborate offsets or side deals to bolster the foreign country and make a major aircraft sale. This can include ensuring that jobs and technologies are transferred to the foreign nation.33 Similarly, consumer-goods manufacturers may be exposed to increased scrutiny in selling their goods abroad in future decades and may have to engage more directly in political activity and offer similar offsets to ensure open markets for their goods.

33 Wayne, Leslie. (16 February 2003). “A Well-Kept Military Secret.” New York Times Online.

Returns management and reverse logistics also are not immune from the influence of geopolitical action or inaction. Many countries do not currently possess the infrastructure or policies to manage waste streams emanating from their economies. As such, some countries have become a dumping ground for end-of-life products such as electronic waste from computers and other high-tech electronic devices, which have extremely short life cycles. However, loss of control and limited policies for managing these returns can and has resulted in contamination and quality issues in the supply chain. For example, counterfeit goods may be returned for credit when they cannot be properly identified as fraudulent products. Additionally, in the case of computer waste sent to China, large quantities were melted down. The lead that Chinese companies recaptured was reintroduced into jewelry that was unknowingly (and sometimes fraudulently) sold in the U.S. These contaminated products resulted in an outcry from U.S. consumers in 2006 following the death of a child in Minnesota who swallowed a piece of contaminated jewelry.34 Such risks have also resulted in increased tracking and inspection costs for companies as they attempt to manage the risk of dangerous returns in an inconsistent and often unregulated environment.

34 Fairclough, Gordon. (12 July 2007). “Lead Toxins Take a Global Round Trip: E-waste from Computers Discarded in West Turns up in China’s Exported Trinkets.” Wall Street Journal.

In the future, it is expected that countries will increase their labor safety practices and environmental pollution standards, making it much more difficult to manage the returns management and reverse supply chains abroad. Additionally, geopolitical tensions and increased regulation may result in harsh penalties for companies that pollute or do not properly manage waste streams and returns abroad. Therefore, companies would be smart to build returns management and waste management systems in advance of future political policy and to meet the reasonably high standards expected by society. Future policy by foreign governments concerning the management of hazardous wastes and the disposal of products may result in higher penalties and costs from making adjustments to the supply chain. It would be a better idea to proactively build a more sustainable system before such regulation is passed.

Finally, supplier relationship management will be greatly affected by growing geopolitical tension and activities in the future. In particular, firms should expect that supply markets will carry additional risks associated with national political interests and policies being implemented across multiple tiers of their supply chains. Increasing resource scarcity and congestion, created by increased population growth and congestion, will cause foreign governments to be more actively involved in regulating and protecting their home markets. Such activity will make it difficult to maintain supplier relationships and operations without violating such policy. Additionally, analyzing, segmenting, and selecting suppliers will become more difficult in the future due to ambiguous risk factors such as political tensions, raw-material constraints, and most-favored-nation status.

Overall, supply complexity is expected to increase as more suppliers enter the global market and bring with them a greater variety of host-nation policies and regulations to understand. This will lead to additional bottlenecks and increased costs in assessing supplier risks in future contracts. Therefore, firms will have to adjust their global sourcing decisions to account for geopolitical and regulatory risks at multiple tiers in their supply chains. In addition, wise firms will begin building excellent relationships with intermediaries in third-party nations to mitigate or even circumvent commodity export restrictions. They also will continue to work with suppliers and foreign governments to gain access to strategically stockpiled supplies and natural resources that are being restricted from trade. Modern organizations should also explore the idea of allowing foreign strategic suppliers to maintain ownership and manage inventories abroad, as long as possible, to limit the risk of geopolitical activity against their assets in the transforming world.