6. Implications for Supply Chain Planning: Demand and Supply Uncertainty

As we stated at the beginning of this book, our overarching purpose is to connect multiple environmental forces that impact (or will impact) human society to the future practice of supply chain management. Therefore, we hope to help business organizations deliver the customer value that defines their missions. More specifically, our goal is to help you understand how the confluence of human population growth and migration, global economic leveling, physical environmental change, and world geopolitical dynamics will affect the efficiency and effectiveness of supply chains designed to create time, place, and form utility for customers. In modern business organizations, these types of utilities are delivered when their supply chains can reliably provide goods and services that impart customer value.

It often surprises business leaders to find that customer satisfaction is not solely, or even primarily, about offering quality goods and services at a fair price, or by creating and marketing offerings that have differentiated features versus those of the competition. Value creation is also highly dependent on the focal organization’s ability to unite the goals of buyers and sellers within the interfunctional relationships that typify world-class supply chain operations. The efficacy of these relationships hinges on the supply chain’s key players, among which are the functional areas of supply chain planning, procurement, goods/service production, and logistics. Each of these functions is necessary in isolation, and they also must work well together for value delivery to occur. The four functions appear in the original version of the popular Supply Chain Operations Reference (SCOR) model of supply chain functionality.1 Managers and academics often call this the “plan, source, make, deliver” sequence.

1 The SCOR model was originally developed by PRTM Consulting and is endorsed by the Supply-Chain Council as a supply chain benchmarking and diagnostics tool.

Consistent delivery of value is the foundation of effective, trusting relationships between functions in the supply chain. In essence, the company’s ability to achieve integration among these four essential operational areas is integral in generating confidence in the company’s ability to fulfill its role in the supply chain, to be a competent partner, and to attract favorable attention from customers and other stakeholders. This is especially true as product offerings themselves become more complex and/or difficult to differentiate within highly competitive industry settings.

The macrotrends we identified in Part I, “Global Macrotrends Impacting the Supply Chain Environment,” are exciting to consider, because they yield a wealth of opportunity for businesses of the future to consider, primarily in the form of new potential markets. Yet, as described in Chapters 2 through 5, these same forces also may inhibit organizations’ ability to maintain high-performing supply chains. They could potentially disrupt how the eight GSCF processes link the four critical functional areas and thereby lead to service problems, supply interruptions, and, ultimately, customer dissatisfaction and lost business. The concern we have for future organizations is that macrotrend-driven process disruptions can meaningfully disable the plan, source, make, deliver operational sequence in the medium to long term and thereby erode hard-earned customer advantages. Customers who fail to extract value from one supplier’s offerings tend to search for substitute value from another source in the short term and replace the failing partner in the medium to long term. Beyond losing business on individual accounts, companies risk disappointing clusters of customers or, worse, gaining a reputation as a high-risk/low-reward supply chain partner.

Part II, “Macrotrend Implications for Supply Chain Functionality,” Chapters 6 through 9, examines the specific impacts of the macrotrends on the four-stage sequence of the supply chain operations functions. This chapter looks at the impacts that demand and supply uncertainty stemming from the macrotrends have on the supply chain planning function. Chapter 7 addresses the issue of resource scarcity and its impacts on the organization’s sourcing/procurement function. Chapter 8 considers how the goods and services production function is and will continue to be hampered by the macrotrend-related impacts. It focuses on how critical flows within the manufacturing environment will be further disrupted in the future. Chapter 9 describes how congestion and decay occurring within the physical infrastructure of many nations will challenge the transportation and logistics managers of the future.

In summary, we suggest that the macrotrends will challenge supply chain process execution across the four key operational areas of the supply chain over the next 20 years or so. The problems should not be insurmountable if future organizations engage in proactive planning. In fact, we estimate that the macrotrends, considered as a whole, will even present strategic opportunities for future market differentiation. This can occur if companies thoughtfully manage the problems and address these problems before competitors do. This chapter begins by looking at the anticipated supply chain planning issues that macrotrend forces will cause. Then it describes some steps that companies can take to mitigate their negative impacts while taking advantage of the opportunities that will arise.

How Supply Chain Plans Improve Performance

With great fanfare, the Chevy Volt was launched onto U.S. automobile dealership floors in late 2010. The Volt boasted a unique, electricity-supported-by-gasoline engine technology.2 Chevrolet anticipated it would sell close to 10,000 Volts in the U.S. during the 2011 fiscal year. However, the maker’s original estimates fell drastically short of expectations when only 7,761 customers who visited dealers in 2011 left with a Volt. This didn’t bode well for the company’s initial 2012 projection of 45,000 units. Indeed, through the first two months of 2012, Chevy had sold only 1,700 more units—far behind planned sales.3

2 Chevrolet Volt. (2012). “Model Overview.” Chevrolet.com. Retrieved 7 August 2012 from www.chevrolet.com/volt-electric-car.html.

3 Hill, Brandon. (5 March 2012). “GM to Suspend Chevy Volt Production for Five Weeks, Cites Soft Demand.” DailyTech.

As a result, early in 2012, many of the company’s workers were furloughed as Chevrolet waited for demand to catch up with supply. Beginning in March 2012, Chevrolet executives decided to halt Volt production for five weeks, citing high inventory levels.4 The problem started at the demand end of the supply chain, where American consumers demonstrated an unexpected reluctance to purchase electric-based automobiles in general. The problem was exacerbated at Chevy when a Volt that had been involved in a collision caught fire three weeks after the accident. A media firestorm ensued, with anti-electric-vehicle activists vociferously proclaiming Volts to be unsafe.5 The public, suddenly wary of the Volt’s new and unusual technology, hesitated before renewing its interest in GM’s flagship new product. The Volt was later deemed to be safe by the U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, and in fact earned its difficult-to-achieve Five-Star Safety Rating. However, the negative publicity spread in early 2012 dramatically affected Volt sales at the showroom for nearly two months. Interestingly, following a change to a California law that allowed electric-motor cars to drive in the high-occupancy highway lane, and as news of the safety rating slowly spread, sales of the Volt rebounded significantly during the summer of 2012. By the end of July, the company had sold nearly 11,000 units—a 40% increase over the entire previous year—and dealers became more worried about keeping units in stock than in holding excess, unsellable inventory.

4 Ibid.

5 Lutz, Bob. (12 January 2012). “Chevy Volt and the Wrong-headed Right.” Forbes.

The Chevy Volt example illustrates the first of our four forward-looking hazards to effective supply chain management in the face of world macrotrends: the inability to optimize supply chain operations due to high demand and supply uncertainty. Best-practice supply chain companies have been investing heavily in different forms of supply chain planning for over a decade. They have kept two simultaneously pursued but (traditionally) countervailing goals in mind: reducing overall supply chain system costs while maximizing customer service. In an ideal scenario, a business would begin each day with no inventory; receive exactly what is needed to fulfill that day’s demand; manufacture and sell exactly what the customers require; deliver in perfect time, place, and condition; and conclude the day with no inventory. Of course, lead times are long and uncertain, and customers and suppliers invariably fail to behave in the highly predictable ways that such a fanciful system would require. So in many cases companies hold inventory in one or more forms as a measure of insurance against customer service failures and stockouts.

In the consumer-goods world, for example, it is nearly impossible for a company to make a perfectly accurate demand forecast. In the case of the Volt, forecasted demand was significantly less than expected in the product’s early stage of the life cycle, leading to drastic measures. Abundant models, techniques, and equations are available for managers to use in predicting demand. However, just as many or more uncontrollable variables can wreak havoc on forecasts, and these can greatly disrupt the supply chains that are designed to follow through on predicted demand. Indeed, in some scenarios, manufacturers and retailers alike have found it best to dispense with forecasting. Instead, they simply produce their wares after, and only after, actual demand is recognized. Regardless of the system employed, inaccuracies in the volume, assortment, and/or location of demand and supply usually cause the supply chain to suffer and costs to rise. Current and future companies must walk a tightrope given the demand and supply fluctuations we predict for the future. Too much product can lead to excess costly inventory, whereas too little can lead to equally (or more) costly stockouts. We expect, as a result of the macrotrends we have identified, that these problems will only accelerate in the coming two decades as demand and supply diversify, migrate, level, disappear, and are otherwise disrupted.

The Supply Chain Planning Function

The supply chain planning function includes planning for both demand and supply so that a business can meet future requirements. This function works to achieve the smallest plausible inventory holdings possible to meet demand, because storing any leftover materials or finished goods saps valuable financial and human resources. However, in many organizations, the concern overriding inventory costs is the modern philosophy that no customer should ever place an order that isn’t fulfilled perfectly. In many cases, customer service becomes the supply chain manager’s primary, or sole, objective. However, this implies that perfectly balancing supply with demand is in reality an unrealistic goal. Even the best supply chain planners don’t carry out this balancing act perfectly. They equalize demand and supply with the smallest possible amount of error, which is measured financially as an aggregation of estimated stockout costs and inventory carrying costs. To think of it another way, the best supply chain planners are those who can best address the demand and supply uncertainties that exist within the system and minimize their financial impact on the company.

Based on this logic, depending on a product’s strategic role for the company and its associated supply and demand market characteristics, one of three types of supply chain systems is planned and implemented. The first of these, an anticipatory system, is used when product demand and supply are relatively predictable and stable, so the competitive focus is placed on cost minimization in the system. In an anticipatory system, the supply chain’s activity is triggered by an initial forecast, which leads to the procurement of materials and manufacture of a product in advance of actual demand. Large-volume procurement and long manufacturing runs reduce direct costs of goods sold, and lean production and logistics can be implemented, all of which facilitate savings that can be passed along to customers. The dark side of an anticipatory system is accumulating finished-goods inventory. If customer tastes change or forecasts are wrong, the company can be stuck with unwanted product and may have to take drastic steps to liquefy the assets.

Alternatively, a responsive system is typically used when variability in the demand for a product is high. Here, the focus is typically more on customer service and satisfaction than on cost savings. In the responsive system, the supply chain process is initiated by an actual customer order, and the source, make, and deliver functions are executed after the fact. The idea is to hold as little inventory as possible and to react quickly when an order is placed. There is an implicit risk of customer stockouts if the needed materials cannot be acquired in time, but the trade-off is that few inventory carrying costs accrue. Planning-based systems generally are inadvisable in such situations. Instead, “agile” systems are created that allow high responsiveness in a very short time. However, agile systems are inherently expensive, and customers tend to absorb a portion of their costs. In the modern, highly customer-focused era, a purely responsive system is sometimes too risky to be palatable for some product scenarios. Due to the costliness of uncertainty in the supply chain and the severe repercussions associated with disappointing customers, a hybrid system has emerged. It mitigates the risks of highly responsive systems by delaying the product’s commitment to a final form or location. This system, known as postponement, allows both manufacturers and customers to hold a smaller amount of partially finished or transported inventory in advance of demand (as in the anticipatory system). The final value is added to the product only following the actualization of that demand (as in the responsive system).

The role of modern supply chain planners is to correct for the errors that inevitably occur in these systems due to demand and supply variability. If both demand and supply could be predicted perfectly, both systems would operate at 100% effectiveness and efficiency. However, this rarely happens, so demand managers have a number of tools with which to “shape” demand to meet available supply. In the short term, these typically include several marketing-based solutions to shift demand for one product to another. These can include pricing or promotional techniques, or geographic postponement, which locates finished product near but not at several final consumption points. It allows final locational diversion to meet exact demand quantities when they occur. In the longer term, more process-oriented solutions such as sales and operations planning (S&OP) and visibility programs are effective in anticipatory systems. Pull systems such as Kanban and form postponement are used in responsive systems.

However different they may be, the anticipatory, responsive, and postponement strategies also have a number of aspects in common. They are all designed to minimize cost while maximizing service, and they are all linked inextricably to demand and supply quantities. Most importantly, their effectiveness is highly susceptible to major shifts in demand and supply quantity and assortment variations. More important, though, is the concept that supply and demand can almost always be brought into closer alignment if managers constantly emphasize doing so, even in the face of short-term hardships. Earlier in the book we introduced the Demand-Supply Integration (DSI) model, which illustrates how important it is to align these perspectives, because the long-term benefits far outweigh the startup costs of doing so. Companies that successfully implement DSI often develop exemplary supply chain processes and customer service proficiency that exceed those of competitors.

For example, careful study would reveal Dell Computer to be a DSI pioneer. When Dell was founded in the 1980s, it applied a “sell what you have” strategy to its operations that quickly put it at the forefront of personal computer sales. One story related to demand/supply misalignment illustrates this fact particularly well. In late 2003, Dell’s operations were disrupted by a U.S. West Coast dockworkers’ strike that shut down an integral part of its supply chain. It was through this channel that Dell received its cathode ray tube (CRT) desktop monitors. Since Dell was using a minimal safety stock strategy, it was unable to fulfill customer orders, and supply fell out of alignment with demand. But Dell’s supply chain planners were prepared for the crisis. Instead of telling its consumers that their computers would be on backorder for the holiday season, Dell offered to upgrade its orders to flat-screen monitors, thereby shaping its demand. This effectively changed the PC market overnight, because Dell’s competitors were unprepared to sell flat-screen monitors at the same margins. By having a DSI contingency plan in place, Dell circumvented its potentially disastrous bottleneck and transformed the entire monitor market in the process.6

6 Stank, Theodore P. and John T. Mentzer. (17 December 2007). “Demand and Supply Integration: A key to improved firm performance.” Industry week.

We see the future business climate as being impacted greatly by the world macrotrends we describe. Therefore, there is much cause to believe that the DSI that enables supply chain-based competitiveness will be greatly affected over the next two decades by the confluence of factors this book addresses. The population and economic shifts, geopolitical issues, and environmental concerns we describe will all affect the demand and supply of critical materials and finished goods companies will manufacture and sell over our time horizon of study. The following section examines the complexities associated with supply and demand uncertainty in the transforming world, as well as what demand managers should consider doing about it.

Macrotrend Demand/Supply Impacts: Supply Chain Planning Considerations

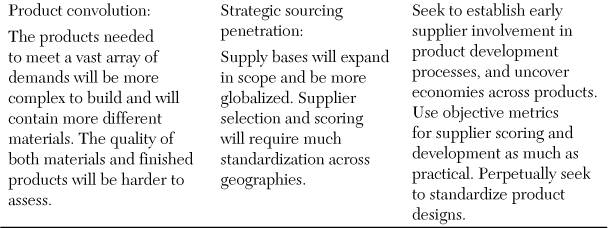

As the supply chains of the future increase in complexity due to the macrotrends we describe, future supply chain planners will need to make a number of adjustments. We propose that five different threats to supply chain performance will result from the macrotrends’ influence, and each will cause a different array of problems for planners. These issues will threaten both demand and supply but will do so to different degrees and in different ways. However, we also suggest that wherever there is a threat to an organic system, there is also usually an opportunity to gain competitive position by solving it. Table 6.1 aligns the expected disruptions with both opportunities and threats emanating from the macrotrend impacts. If organizations pay thoughtful attention to these issues’ impact on relevant demand and supply markets, we hope planners can leverage these issues competitively as they devise future supply chain strategies. We conclude this chapter by summarizing the visions presented in Table 6.1, with an eye on generating supply chain planning considerations for supply chain planners and managers moving forward.

Table 6.1. Macrotrend Impacts, Supply Chain Implications, and Planning Considerations

First, based on our earlier discussions of anticipated world changes, we predict that demand for goods and services will become increasingly volatile, while at the same time leveling somewhat across world regions. We see demand becoming increasingly unstable for all but the staples. Shopping tastes, channels, and frequency will increase, particularly in the resource-rich regions as those nations develop consumer classes. The proliferation of the Internet as both a promotional avenue and a marketing channel will force companies to wait longer to commit goods to final form. It also will severely curtail the utility of forecasting for products serving all but the most basic needs.

In light of these predictions, we suggest that future supply chain planners will be greatly concerned with the proliferation of products that the growing and moving world consumer class will demand. We believe that the leading-edge supply chain companies will deploy responsive and postponement-based systems much more widely across the product mix, with manufacturing and stockpiling of partially finished goods a key strategy for minimizing pipeline inventory. The blended use of form and geographic postponement will become more standard. Outbound distribution centers will increasingly need semi-skilled manufacturing labor (painters, pressers, packagers) to complete the product before it is shipped to retail or directly to the customer. In cases where forecasting is necessary, we also find opportunity for the utilization of regional social scientists who understand where people are moving, how their wealth levels are changing, and where and how the next demand changes can be expected to appear.

Second, our studies of the economic leveling macrotrend lead us to believe that the “power of the customer” is quickly becoming a worldwide mantra. It will greatly affect how manufacturers and retailers of shopping and specialty goods operate their supply chains over the next two decades. We are already seeing evidence that consumer expectations for product availability, quality, and customization are accelerating in developing nations. For example, it is expected that by the end of 2015, emerging markets such as China, Brazil, and India should account for more than 50% of luxury-goods sales. In fact, China already accounts for approximately 10% of the luxury-goods market worldwide.7

7 “Is FDI reform the answer to the India problem?” (26 January 2012). The Business of Fashion.

However, even though quality and service standards are indeed growing worldwide, the supply chain processes that support these have often been secondary concerns in many world regions. For example, India still greatly lags behind China in luxury-goods sales despite its booming economy. In 2011, India only made up approximately 1% to 2% of the global luxury-goods market, primarily due to supply-side issues. Some of the supply chain problems in India include foreign investment regulations and high import duties.8 However, a bigger problem may be the lack of retail space and locations to actually sell luxury items. Many luxury brands try to currently collocate with upscale hotels. Few have their own actual storefront locations in India. In addition, culture has been another impediment in India, where luxury brands have struggled to tailor their offerings to local tastes and tradition. Trying to do so has been no guarantee of success. In the future, it will become important for global manufacturers and retailers to develop competencies in quality management that are both clear and consistent with the local market cultures. The best way we know of to do this is to collaborate with locally headquartered or operational partners via joint ventures (as an entry strategy) or strategic alliances (for the purposes of leveraging an established partner’s knowledge of the local/regional supply market). Where partners are unavailable, objective measures may provide the greatest benefit in terms of partner identification. Creating extensive and rigorous supplier certification and development programs, paired with highly specified metrics for quality, probably is the best substitute. Additionally, as customer tastes advance in formerly more embryonic markets, establishing “localized” customer service functions will become vital to minimize returns costs (which will be substantial) and maximize customer value streams. Firms that are seeking to enter and compete in evolving markets can get a leg up by providing great service along with solid offerings. They may capture durable market share before their industry matures there.

8 Ibid.

Third, due to the forces we’ve described, we expect that more demand centers will emerge that will stretch the current supply chain network(s) of many companies out of relative equilibrium. The combination of growing population and resource imbalances will spawn new locations for both primary and secondary demand. The result will be that supply chains of the future will be much more complex. This will be true primarily because of the necessary addition of nodes and links to ever-lengthening chains, as well as the increased prevalence of both global and local outsourcing. Products demanded within these locations will be of greater assortment, and the current networks won’t reach close enough to serve demand adequately. To close the gaps, companies will need to work on both the demand and supply angles of the problem. Supply bases for mission-critical commodities will globalize, and new nodes in the network (plants and distribution hubs) will need to be established. Firms with the best insight into nation-specific real estate and legal/contracting services will have key advantages, as will those that can secure third- or fourth-party logistical services dedicated to the regions of critical interest. Yet, this type of expansion could also be the source of supplier and SKU proliferation, which are expensive problems even today. Firms should seek flexible but comprehensive and legally tenable contracts with regional suppliers to fill the key gaps. If possible, they also should develop strategic relationships in geographically advantageous areas several years before they are forecasted as necessary.

An alternative to this collection of plans, if feasible, may be the development of the previously mentioned concept of “flexworks.” These are flexible networks that adapt to an order’s product, customer, environmental, and transportation availability aspects in real time. The primary problem we foresee with the networks of the future is that they will increase dramatically in scope while infrastructure links and nodes will lag in development, and/or the need for change will come quickly and often. Our vision for flexworks includes multi-industry sharing of transportation that would allow load-sharing opportunities to reveal themselves in real time based on the technological location of transportation assets, distribution dock space, and labor. Suppose participants could be induced financially via cost savings to engage with inventory and transportation visibility tools. Networks could be calibrated and recalibrated in real time to handle loads taking many different routes to the same destination. This could be done by acquiring and paying for available capacity as it is located using a global, multi-industry software application. If enough “members” could be solicited to share, buy, and sell excess capacity on live markets, extended reach and the capability to handle problems and mitigate disruptions could be minimized. Security would, of course, be a major issue. But we are confident that a set of uniform standards could be devised that would provide acceptable ranges of risk for most common goods firms and industries.

Fourth, we expect that the supply chain processes that connect the four supply chain operational areas within the business enterprise will increase in both time and distance. They will have greater lead times, and constant reengineering will be required to keep the supply chain functioning near its optimum levels. The new demand centers we expect to emerge will probably often do so in areas of the world where little advanced infrastructure exists and/or that are far from our fixed supply chain assets. Establishing cooperative transportation agreements with noncompeting (or competing!) partners may be critical if a region explodes in demand. Likewise, intergovernmental partnerships between the host and home nation for infrastructure development may ease the costs of resource extraction if cost- and gain-sharing agreements can be forged. If and until infrastructure linkages and supply chain pipelines can be developed, geographic postponement conducted in a nearby region may be the ticket to entry. This is true particularly if a strategically located facility can be used as a consolidation point for distribution throughout the region. To this end, building bridge locations with partners located near, but not in, potentially exploding demand markets may be the ticket.

Finally, we expect that differences in customer preferences, in combination with numerous raw-materials shortages, will greatly increase products’ complexity and quality variation. However, raw-materials shortages, consumer preference diversity, and the perpetual need to innovate will spawn more, new, and increasingly complex offerings that will require equally new and different supply chain support to flourish. For example, in an attempt to increase the diversity of its menu, McDonald’s Corp. considered adding a new shrimp salad offering. However, when the impact of the new product on the supply chain was analyzed, it quickly became evident that the demand generated by the large number of McDonald’s locations would be so great that it might actually deplete the nation’s supply of shrimp.9 Global supply bases will have to expand greatly, and measuring and evaluating both current and potential suppliers will become an arduous and overwhelming task. We advise supply chain planners of the present and future to work closely with supply managers. Gain early supplier involvement in the development of new offerings that contain new, different, or rare raw materials. Also seek to uncover sources (and designs) that allow for maximum planning synergy across products. This may be anathema to some product design engineers, because it might cause slightly suboptimal performance in certain products in exchange for enhancing the profitability of the entire product portfolio. As a corollary, we suggest that great opportunity for best practice comes in integrating demand management with product development and commercialization. Companies of the future would seek to standardize designs across different lines and categories, keeping commodity leveraging in mind.

9 Bissonette, Zac. (30 January 2007). “The New McDonald’s.” www.bloggingstocks.com.

As supply chains transform to meet the threats posed by these issues, we expect that supply chain planners of the future will take a more proactive role in driving organizational successes. Of course, the ultimate outcomes will be tied closely to whether their plans can ultimately be executed. These are the issues we address next.