1. Demand/Supply Integration

One of the companies that participated in the DSI/Forecasting Audit research was in the apparel industry. This company, a manufacturer and marketer of branded casual clothing, had very large retail customers that contributed a large percentage of overall revenue. Understandably, keeping these large retail customers in stock was very important to the success of this company. If these retailers’ orders could not be filled, then out-of-stock conditions would result, with not only lost sales as the consequence, but also potential financial penalties for failure to satisfy these retailers’ stringent fill-rate expectations.

As is the case for many companies in this industry, considerable manufacturing capacity had been offshored to sewing operations in Asia. This strategy helped to keep unit costs down, but it also had a negative impact on the company’s responsiveness and flexibility. At the time of our audit, the research team heard about a communication disconnect between the supply chain and the sales organizations at this company. A variety of problems had left the company with significant capacity shortages. Although these problems were solvable in the long run, in the short term, the company was having significant fill-rate problems with some of its largest, most important retail customers. Some of the most popular sizes and styles of clothing were in short supply, and customers were not happy. Supply chain personnel were working hard to address these problems, but in the short term, there was little to be done. Although these supply chain problems were impacting the company’s largest, most important customers, personnel from the field sales organization were being incentivized to open new channels of distribution and locate new customers to carry their brands. As one supply chain executive told this story, she said in exasperation, “We’re out of stock at Wal-Mart, and they’re signing up new customers! What the hell is going on here?”

This example is a classic illustration of what can happen when Demand/Supply Integration, or DSI, is not a part of the fabric of an organization. This chapter explores the essence of DSI, distinguishes it from Sales and Operations Planning (S&OP), articulates from a strategic perspective what DSI is designed to accomplish, describes some typical aberrations from the “ideal state” of practice, and describes some characteristics of successful DSI implementations.

The Idea Behind DSI

Demand/Supply Integration (DSI), when implemented effectively, is a single process to engage all functions in creating aligned, forward-looking plans and make decisions that will optimize resources and achieve a balanced set organizational goals. Several phrases in the preceding sentence deserve further elaboration. First, DSI is a single process. The idea is that DSI is a “super-process” containing a number of “subprocesses” that are highly coordinated to achieve an overall aligned business plan. These subprocesses include demand planning, inventory planning, supply planning, and financial planning. Second, it is a process that engages all functions. The primary functions that must be engaged for DSI to work effectively are sales, marketing, supply chain, finance, and senior leadership. Without active, committed engagement from each of the functional areas, the strategic goals behind DSI cannot be achieved. Third, it is designed to be a process that creates aligned, forward-looking plans and makes decisions. Unfortunately, when DSI is not implemented well, it often consists of “post-mortems,” or discussions of “why we didn’t make our numbers last month.” The ultimate goal of DSI is business planning—in other words, what steps will an organization take in the future to achieve its goals?

Our research has shown that three important elements must be in place for DSI to operate effectively: culture, process, and tools. An organization’s culture must be focused on transparency, collaboration, and commitment to organization-wide goals. Processes must be clearly articulated, documented, and followed to ensure that all planning steps are completed. Effective tools, normally thought of as information technology tools, are also needed to provide the right information at the right time to the right people.

How DSI Is Different from S&OP

Many authors have, over the last 20+ years, written about Sales and Operations Planning (S&OP), and to some, the earlier description of DSI might sound like little more than a rebranding of S&OP. Unfortunately, S&OP has a bit of a “bad name,” thanks to ineffective process implementation. In our observation of dozens of S&OP implementations, we’ve seen several common implementation problems that have contributed to a sense of frustration with the effectiveness of these processes.

First, S&OP processes are often tactical in nature. They often focus on balancing demand with supply in the short run, and turn into exercises in flexing the supply chain, either up or down, to respond to sudden and unexpected changes in demand. The planning horizon often fails to extend beyond the current fiscal quarter. With such a tactical focus, the firm can miss out on the chance to make strategic decisions about both supply capability and demand generation that extend further into the future, which can position the firm to be pro-active about pursuing market opportunities.

Second, S&OP process implementation is often initiated, and managed, by a firm’s supply chain organization. In our experience, these business-planning processes are put into place because supply chain executives are “blamed” for failure to meet customer demand in a cost-effective way. Inventory piles up, expediting costs grow out of control, and fill rates decline, causing attention to be focused on the supply chain organization, which immediately points at the “poor forecasts” that come out of sales and marketing. The CEO gets excited, S&OP is hailed as the way to get demand and supply in balance, and the senior supply chain executive is tasked with putting this process in place. Where the disconnect often takes place, however, is with lack of engagement from the sales and marketing functions in the organization—the owners of customers and the drivers of demand. Nothing can make S&OP processes fail any faster than having sales and marketing be non-participants. In more than one company we’ve worked with, people describe S&OP as “&OP”—meaning that “Sales” is not involved.

Third, the very name “Sales and Operations Planning” carries with it a tactical aura. As argued in an upcoming section, many more functions besides Sales and Operations must be involved in order for effective business planning to take place. Without engagement from marketing, logistics, procurement, and particularly finance and senior leadership, these attempts at integrated business planning are doomed to being highly tactical and ultimately disappointing.

Thus, although the goals of S&OP are not incompatible with the goals of DSI, the execution of S&OP often falls short. Perhaps a new branding campaign is indeed needed, because in many companies, S&OP carries with it the baggage of failed implementations. Demand/Supply Integration is an alternative label and a new opportunity to achieve integrated, strategic business planning.

Signals that Demand and Supply Are Not Effectively Integrated

As our research team has worked with dozens of companies over the past 15 years, we have witnessed many instances where demand and supply are not effectively integrated. Commonly, our team is called in to diagnose problems with the forecasting and business planning processes at companies because some important performance metric—often inventory turns, carrying costs, expedited freight costs, or fill rates—have fallen below targeted levels. After we arrive onsite, we frequently hear about problems like those in the following list. Ask yourself whether any of these situations apply to your company:

• Does manufacturing complain that sales overstates demand forecasts, doesn’t sell the product, and then the supply chain gets blamed for too much inventory?

• Does the sales team complain that manufacturing can’t deliver on its production commitments and it’s hurting sales?

• Does manufacturing complain that the sales team doesn’t let them know when new product introductions should be scheduled, and then they complain about missed customer commitments?

• Does the sales team initiate promotional events to achieve end-of-quarter goals, but fail to coordinate those promotional activities with the supply chain?

• Does the business not take advantage of global supply capabilities to profitably satisfy regionally?

• Are raw material purchases out of alignment with either production needs or demand requirements?

• Does the business team adequately identify potential risks and opportunities well ahead of time? Are alternatives discussed and trade-offs analyzed? Are forward actions taken to reduce risk and meet goals, or are surprises the order of the day?

If these are common occurrences at your company, then the case might be that your Demand/Supply Integration processes might not be living up to their potential. The case might also be that one or more of the critical subprocesses that underlie the DSI “superprocess” might be suffering from inadequate design or poor execution.

The Ideal Picture of Demand Supply Integration

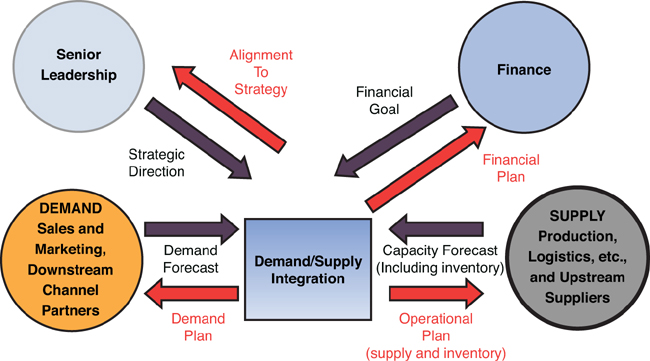

Figure 1-1 represents an “ideal state” of DSI. The circles represent functional areas of the firm, the rectangle represents the super-process of DSI, the dark gray (dark purple in the e-book) arrows leading into the DSI process represent inputs to the process, and the lighter gray (red in e-book) arrows leading out of DSI represent outputs of the process.

Figure 1-1. Demand/Supply Integration: the ideal state

It all begins with the two dark gray (dark purple) arrows labeled “Demand Forecast” and “Capacity Forecast.” As future chapters clearly articulate, the demand forecast is the firm’s best “guess” about what customer demand will consist of in future time periods. It should be emphasized that this is indeed a guess. Short of having a magic crystal ball, uncertainty exists around this estimate of future demand. Of course, the further into the future one estimates demand, the greater the uncertainty that exists. Similarly, the “Capacity Forecast” represents the best “guess” about what future supply capability will be. Just as is the case with the demand forecast, uncertainty surrounds any estimate of supply capability. Raw material or component part availability, labor availability, machine efficiency, and other supply chain variables introduce uncertainty into estimates of future capacity levels.

Let’s begin with a simple example as a way of explaining how the DSI process needs to work. Assume that the “Demand” side of the business—typically sales and marketing, with possible input from channel partners—goes through an exercise in demand forecasting, and concludes that three months from the present date, demand will consist of 10,000 units of a particular product. Let’s further assume that this demand forecast is reasonably accurate. (I know; that may be an unrealistic assumption, but let’s assume it regardless!) Now, concurrently, the “Supply” side of the business—operations, logistics, procurement, along with input from suppliers—conducts a capacity forecast and concludes that three months from the present date, supply capability will consist of 7,500 units. Note that this outcome is far from atypical. The fact is that demand and supply are usually NOT in balance. So, more demand exists than supply. The question is, “What should the firm do?”

Several options exist:

• Dampen demand. This option could be achieved in a number of ways. For example, the forecasted level of demand assumes a certain price point, a certain level of advertising and promotional support, a certain number of salespeople who are selling the product with certain incentives to do so, a certain level of distribution, and so forth. Any of these demand drivers could be adjusted in an effort to bring demand into balance with supply. Thus, some combination of a price increase or a reduction in promotional activity could dampen demand to bring it in line with supply.

• Increase capacity. Just as the demand forecast carries with it certain assumptions, so, too, does the capacity forecast. Capacity could be increased through adding additional shifts, outsourcing production, acquiring additional sources of raw materials or components, speeding up throughput, and so forth.

• Build inventory. Often, the case is that in some months, capacity exceeds demand, whereas in other months, demand exceeds capacity. Rather than tweaking either demand or supply on a month-by-month basis, the firm could decide to allow some inventory to accumulate during excess capacity months, which would then be drawn down during excess demand months.

These are all worthy options for solving the “demand is greater than capacity” problem. The question, of course, is “Which one is the best for solving the short-term problem, while at the same time achieving a variety of other goals?”

The answer is, “It depends.” It depends on the costs of each alternative and the strategic desirability of each alternative. Because each situation is unique, with different possible alternatives that carry with them different cost and strategic profiles, the need exists to put these available alternatives in front of knowledgeable decision-makers who can determine which is the best course of action. This is the purpose of Demand/Supply Integration, represented as the rectangle in Figure 1-1. The “Financial Goal” arrow represents the financial implications of each alternative, and the “Strategic Direction” arrow represents the strategic implications of each alternative. All these pieces of information from all these different sources—the Demand Forecast, the Capacity Forecast, the Financial Goal, and Strategic Direction—must be considered to make the best possible decisions about what to do when demand and supply are not in balance.

This simple example could be turned in the other direction. Suppose that the demand forecast for 3 months hence is 10,000 units, and that the capacity forecast for that same time period is 15,000 units. Now, the firm is faced with the mirror image of the first situation. Instead of dampening demand with price increases or reduced promotional support, the firm can increase demand with price reductions or additional promotional support. Instead of increasing production with additional shifts or outsourced manufacturing, the firm can reduce production with fewer shifts or taking capacity down for preventive maintenance. Instead of drawing down inventory, the firm can build inventory. Once again, the answer to the question of “What should we do?” is “It depends.” Again, the correct answer is a complex consideration of costs and strategic implications of each alternative. The right people need to gather with the right information available to them to make the best possible decision—once again, DSI.

To further illustrate this “ideal state” of DSI, consider another example. This time, assume that the demand forecast for 3 months hence, and the capacity forecast for 3 months hence, are both 10,000 units (an unlikely scenario, but assume it anyway). Further, assume that if the firm sells those 10,000 units 3 months hence, the firm will come up short of its financial goals, and the investment community will hammer the stock. Now what? Now, both demand side and supply side levers must be pulled. Demand must be increased by changing the assumptions that underlie the demand forecast. Prices could be lowered, promotional activity could be accelerated, new distribution could be opened, and new salespeople could be hired. Which choice is optimal? Well, it depends. Simultaneously, supply must be increased to meet this increased demand. Extra shifts could be added, production could be outsourced, or throughput could be increased. Which choice is optimal? Well, it depends. The right people with the right information need to gather to consider the alternatives—again, DSI.

So far we have covered the inputs to the DSI process. An unconstrained forecast of actual demand is matched up against the forecasted capacity to deliver products or services. Within the Demand/Supply Integration process, meetings occur where decisions are made about how to bring demand and supply into balance, both in a tactical, short-term context and in a strategic, long-term context. Financial implications of the alternatives are provided from finance, and strategic direction is provided by senior leadership. However, Figure 1-1 also contains arrows that designate outputs from the DSI process. You should look at these outputs as business plans. Three categories of business plans result from the DSI process, as follow:

• Demand plans represent the decisions that emerge from the DSI process that will affect sales and marketing. If prices need to be adjusted to bring demand into balance with supply, then sales and marketing need to execute those price changes. If additional promotional activity needs to be undertaken to increase demand, then sales and marketing need to execute those promotions. If new product introductions need to be accelerated (or delayed), then those marching orders need to be delivered to the responsible parties in sales and marketing. The vignette from the beginning of the chapter represented a disconnect associated with communicating and executing these demand plans.

• Operational plans represent the decisions from the DSI process that will affect the supply chain. Examples of these operational plans are production schedules, inventory planning guidelines, signals to procurement that drive orders for raw materials and component parts, signals to transportation planning that drive orders for both inbound and outbound logistics requirements, and the dozens of other tactical and strategic activities that must be executed in order to deliver goods and services to customers.

• Financial plans represent signals back into the financial planning processes of the firm, based on anticipated revenue and cost figures that are agreed to in the DSI process. Whether the activity is financial reporting to the investment community or acquisition of working capital to finance ongoing operations, the financial arm of the enterprise has executable activities that are dependent upon the decisions made in the DSI process about how demand and supply will be balanced. Lastly, those signals come back to the senior leadership of the firm that the decisions that have been reached align with the strategic direction of the firm. These signals are typically delivered during the executive DSI meetings, which are corporate leadership sessions where senior leaders are briefed on both short- and long-term business projections.

Thus, in its ideal state, DSI is a business planning process that takes in information about demand in the marketplace, supply capabilities, financial goals, and the strategic direction of the firm, and makes clear decisions about what to do in the future.

DSI Across the Supply Chain

Up until now, we have talked about the need to integrate demand and supply within a single enterprise. In other words, how can insights about demand levels that might be housed in sales or marketing be shared with those who need to plan the supply chain? DSI processes are the answer. However, the ideal state of DSI doesn’t need to be limited to information sharing within a single enterprise. Figure 1-2 represents a vision of how DSI can be expanded to encompass an entire supply chain.

Figure 1-2. Demand/Supply Integration across the supply chain

Figure 1-2’s representation of DSI is a simpler version of Figure 1-1 depicted in a simplified supply chain. The straight, vertical arrows show the possibilities for collaboration. First consider the arrow that leads from the customer’s “Demand Plan” to the manufacturer’s “Demand Forecast.” Imagine, for example, that the “customer” in Figure 1-2 is a computer company, and the “manufacturer” is a company that produces microprocessors for the computer industry. The computer company’s demand plan will include various promotional activities that it plans to execute in future time periods to take advantage of market opportunities. The manufacturer, the microprocessor company, would benefit from knowing about these promotional activities, because it could then be able to anticipate increases in demand from this customer. Such knowledge would be incorporated into the demand forecast for the microprocessor company.

Next consider the arrow that points from the manufacturer’s “Operational Plan” to the customer’s “Capacity Forecast.” When the microprocessor company completes its DSI process, one output is an operational plan that articulates the quantity of a particular microprocessor that it intends to manufacture in future time periods. The customer, the computer company, would benefit from knowing this anticipated manufacturing quantity, particularly if it means that the microprocessor company will not be able to provide as much product as the computer company would like to have. Such a shortage would need to be a part of the computer company’s capacity forecast, because this shortage will influence the results of the DSI process at the computer company. Thus, the outputs of the DSI processes at one level of the supply chain can, and should, become part of the inputs to the DSI process at other levels of the supply chain.

This same logic would apply if the “customer” were a retailer and the “manufacturer” were a company that sold its products through retail. The retailer’s promotional activity, as articulated in the retailer’s demand plan, is critical input to the manufacturer’s demand forecast. Also, the manufacturer’s projected build schedule, as articulated in the manufacturer’s operational plan, is critical input to the retailer’s capacity forecast. Companies use a variety of mechanisms to support this level of collaboration across the supply chain. These mechanisms can be as simple as a formal forecast being transmitted from the “customer” to the “manufacturer” on a regular basis. The mechanism can also be much more formalized, and conform to the Collaborative Planning, Forecasting, and Replenishment (CPFR) protocol as articulated by Voluntary Interindustry Commerce Solutions (VICS). Regardless of how this collaboration is executed, the potential exists for significant enhancements to overall supply chain effectiveness when DSI processes are implemented across multiple levels of the supply chain.

Typical DSI Aberrations

The “ideal state” of DSI as depicted in both Figures 1-1 and 1-2 are just that—ideal states. Unfortunately, a variety of forces often result in actual practice being far removed from ideal practice. I have observed a variety of “aberrations” to the ideal states articulated earlier, and three are so common that they are worth noting.

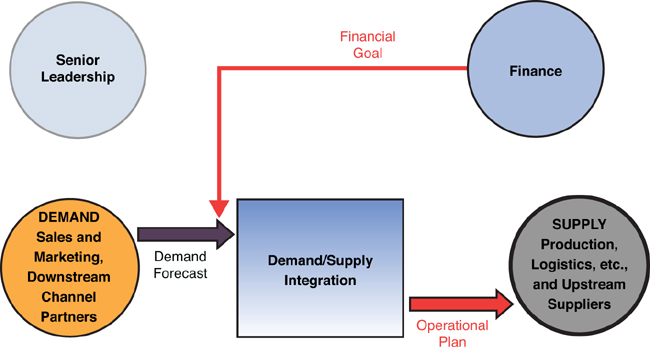

The first, and perhaps most insidious, of these DSI aberrations is depicted in Figure 1-3. The figure is simplified to highlight the aberration, which is known as plan-driven forecasting. Previously in this chapter, I discussed the not-uncommon scenario where forecasted demand fails to reach the financial goals of the firm. In the ideal state of DSI, that financial goal is one of the inputs to the DSI process, where decisions are made about how demand (and if necessary, supply) should be enhanced to achieve the financial goals of the firm. In a plan-driven forecasting environment, however, the financial goal does not lead to the DSI process. Rather, it leads to the demand forecast. In other words, rather than engaging in a productive discussion about how to enhance demand, the message is sent to the demand planners that the “right answer” is to simply raise the forecast so that it corresponds to the financial goal. This message can be simple and direct—“raise the forecast by 10%”—or it can be subtle—“the demand planners know that their forecast had better show that we make our goals”—but either way, the plan-driven forecasting aberration is insidious because it results in a forecasting process that loses its integrity. If downstream users of the forecast—those who are making marketplace, supply chain, financial, and strategic decisions—know that the forecast is simply a restatement of the financial goals of the firm, and not an effort to predict real demand from customers, then those users will stop using the forecast to drive their decisions. I have observed two outcomes from plan-driven forecasting:

• Supply chain planners go ahead and manufacture products that correspond to the artificially inflated forecast; the result is excess, and potentially obsolete, inventory.

• The supply chain planners say to themselves, “I know darn well that this forecast is a made-up number and doesn’t represent reality. And since I own the inventory that will be generated by overproducing, I’m just going to ignore the forecast and do what I think makes sense.” Here, the result is misalignment with the demand side of the company.

Figure 1-3. Typical DSI aberration: plan-driven forecasting

In both cases, plan-driven forecasting results in a culture where the process loses integrity, and forecast users stop believing what forecasters say.

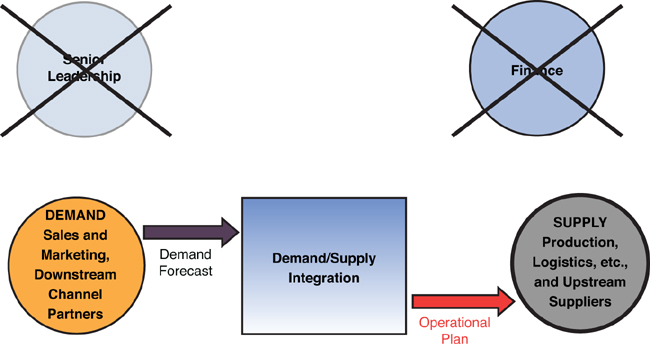

Figure 1-4 shows the second DSI aberration, what I call DSI as a tactical process. In this scenario, the responsibility of the demand side of the enterprise is to come up with a demand forecast, which is then “tossed over the transom” to the supply side of the enterprise, which then either makes its plans based on the forecast, or not. Often, no DSI process really is in place—no scheduled meetings where demand-side representatives and supply-side representatives interact to discuss issues or constraints. When this aberration is in place, significant risk exists for major disconnects between sales and marketing and supply chain. Without the information-sharing forum that a robust DSI process provides, both sides of the enterprise usually develop a sense of distrust, neither understanding nor appreciating the constraints faced by the other. In addition to the siloed culture that results from this aberration, the lack of engagement from either senior leadership or finance makes this approach to DSI extremely tactical. Oftentimes, the forecasting and planning horizons are very short, and opportunities that might be available to grow the business might be sacrificed, because demand and supply are not examined from a strategic perspective. In this scenario, it is nearly impossible for DSI to be a process that “runs the business.” Instead, it is limited to a process that “runs the supply chain,” and engagement from sales and marketing leadership becomes very challenging.

Figure 1-4. Typical DSI aberration: DSI as a tactical process

Figure 1-5 shows the final common aberration to the ideal state of DSI: lack of alignment with sales and marketing. In this situation, little, if any, communication gets back to the demand side of the enterprise concerning the decisions made in the DSI process. This aberration is most problematic when capacity constraints are in force, resulting in product shortages or allocations. Recall the scenario described at the beginning of this chapter, where the sales organization at the apparel company was incentivized to sign up new accounts, while production problems were affecting deliveries to the firm’s largest, most important current customer. As previously illustrated, the discussions that occur in the DSI process often revolve around what actions should be taken when demand is greater than supply. However, if no effective feedback loop exists that communicates these decisions back to the sales and marketing teams, then execution is not aligned with strategy, and bad outcomes often occur.

Figure 1-5. Typical DSI aberration: lack of alignment with sales and marketing

The aberrations described here are examples of typical problems faced by companies when their DSI processes are not executed properly. Aberrations like these often exist, even when the formal process design is one where these aberrations would be avoided. However, siloed cultures, misaligned reward systems, lack of training, and inadequate information systems can all conspire to undermine these process designs. The reader is encouraged to look carefully at Figure 1-1, which represents the ideal state of DSI, and carefully think through each of the input and output arrows shown in the figure. Wherever an arrow is missing, or pointed at the wrong place, an aberration occurs. Identifying gaps in the process is the first step to process improvement.

DSI Principles

Now that the ideal structure of DSI has been described, along with typical aberrations to that ideal, discussing some of the guiding principles that should drive the implementation of DSI at any company is appropriate. Three guiding principles are that

• DSI should be demand driven. Many years of supply chain research conclude that the most successful and effective supply chains are demand driven. In other words, supply chains are most effective when they begin with the voice of the customer. DSI processes should reflect this demand-driven orientation. The “Demand Forecast” arrow in Figure 1-1 represents this principle. The demand forecast is the voice of the customer in the DSI process. However, in too many instances, this customer voice is not as well represented as it should be, because sales and marketing are not as committed to or engaged in the process as they need to be. Because of culture, driven by measurement and reward systems, the weak link in many DSI implementations is the engagement from sales and marketing. Chapters 4, “Qualitative Forecasting Techniques” and 5, “Incorporating Market Intelligence into the Forecast,” explore this phenomenon in greater detail.

• DSI should be collaborative. Figure 1-1 indicates that inputs to the process come from a variety of sources, both internal and external: sales, marketing, operations, logistics, purchasing, finance, and senior leadership represent the typical internal sources of information, and important customers and key suppliers represent the typical external sources of information. For this information to be made available to the process, a culture of collaboration must be in place. This culture of collaboration is one where each individual who participates in the process is committed to providing useful, accurate information, rather than pursuing individual agendas by withholding or misconstruing information. Establishing such a culture of collaboration is often the most challenging aspect of implementing an effective DSI process. Senior leadership must play an active role in developing and nurturing such a culture.

• DSI should be disciplined. When I teach undergraduate students, who often have little experience working in complex organizations, I often make the point that “what goes on in companies is meetings. You spend all your time either preparing for meetings, attending meetings, or doing the work that results from meetings.” DSI is no different. The core of effective DSI processes are a series of meetings, and for DSI to be effective, the meetings that constitute the core of DSI must also be effective. This means discipline. Discipline comes in several forms. The right people must be in attendance at the meetings, so decisions about balancing demand and supply can be made by people who have the authority to make those decisions. Agendas must be set ahead of time and adhered to during the meetings. Discussion must focus on looking forward in time, rather than dwelling on “why we didn’t make our numbers last month.” To develop and maintain such discipline, an organizational structure must be in place where someone with adequate organizational “clout” owns the process and where senior leadership works with this process owner to drive process discipline. Once again, this points to organizational culture being critically important to DSI process effectiveness.

When these principles are embraced, then the “magic” of DSI can be realized, as shown in Figure 1-6.

Figure 1-6. DSI “magic” comes from hitting the sweet spot.

The “sweet spot” shown in Figure 1-6 is the intersection of three conflicting organizational imperatives: maximizing customer service (having goods and services available to customers at the time and place those customers require), minimizing operating costs (efficient manufacturing processes, minimizing transportation costs, minimizing purchasing costs, and so on), and minimizing inventory. This “sweet spot” can be achieved, but it requires DSI implementation that is demand driven, collaborative, and disciplined.

Critical Components of DSI

This book is not intended to be a primer on the detailed implementation of DSI. Many other books do an outstanding job of providing that level of detail. However, in my experience of working with dozens of companies, I have observed that five critical components must be in place for DSI to work well. These components are

1. Portfolio and product review

2. Demand review

3. Supply review

5. Executive review

The following sections discuss each of these in terms of high-level objectives rather than tactical, implementation level details.

Portfolio and Product Review

The portfolio and product review is often absent from DSI processes, but including this step represents best practice. Its purpose is to serve as input to the demand review for any changes to the product portfolio. These changes typically come about from two sources: new product introductions and product (SKU) rationalization. New product forecasting is a worthy subject for an entire book,1 and as such, I will not dwell on it here other than to say that predicting demand for new products, whether they are new-to-the-world products or simple upgrades to existing products, represents a complex set of forecasting challenges. Too often, new product development (NPD) efforts are inadequately connected to the DSI process, and the result is lack of alignment across the enterprise on the effect that new product introductions will have on the current product portfolio.

1 An excellent book-length primer on new product forecasting is New Product Forecasting: An Applied Approach, by Kenneth B. Kahn, M.E. Sharpe, 2006.

Another key element of the portfolio and product review stage of the DSI process is product, or SKU, rationalization. It is the rare company that has a formal, disciplined process in place for ongoing analysis of the product portfolio, and the result of this lack of discipline is the situation described by a senior supply chain executive at one company: “We’re great at introducing new products, but terrible at killing old ones.” This unwillingness to dispassionately analyze the overall product portfolio on an ongoing basis leads to SKU proliferation, and this leads to often unnecessary, and costly, supply chain complexity. By including product, or SKU rationalization as an ongoing element of the DSI process, companies have a strong foundation that permits the next step—the demand review—to accurately and effectively assess anticipated future demand across the entire product portfolio.

Demand Review

The demand review is, in essence, the raison d’etre for this book. The ultimate objective of the demand review is an unconstrained, consensus forecast of future demand. This meeting should be chaired by the business executive with P&L responsibility for the line of business, which constitutes the focus of the DSI process. This could be the company as a whole, or it could be an individual division or strategic business unit (SBU) of the company. Key, decision-capable representatives from the demand side of the enterprise should attend the demand review meeting, including product or brand marketing, sales, customer service, and key account management. One company that I’ve worked with has a protocol for its monthly demand review meeting. Sales and marketing personnel are invited and expected to attend and actively participate. Supply chain personnel are invited, but attendance is optional, and if they attend, they are not allowed to participate in the discussion! The intent is that the supply chain representatives are not allowed to chime in with statements like, “Well, we can’t supply that level of demand.” This protocol is one way that this company keeps the focus on unconstrained demand.

Because Chapter 8, “Bringing It Back to Demand/Supply Integration: Managing the Demand Review,” covers the details of preparing for and conducting the demand review, I do not dwell on the specific agenda items or outcomes of the demand review here. For now, suffice it to say that the critical output of this stage in DSI is a consensus forecast of expected future demand.

Supply Review

The supply chain executive with relevant responsibility for the focal line of business being planned by the DSI process should chair the supply review meeting. The purpose of the supply review is to arrive at a capacity forecast, defined as the firm’s best guess of its ability to supply products or services in some future time period, given a set of assumptions that are both internal and external. In addition, the supply review is that step in the DSI process where the demand forecast is matched up with the capacity forecast, and any gaps are identified, resolved, or deferred to future meetings.

The capacity forecast is determined by examining a number of pieces of information that are focused on the firm’s supply chain. The components include supplier capabilities, actual manufacturing capabilities, and logistics capabilities. Supplier capabilities are typically provided by the purchasing, or procurement, side of the supply chain organization, and reflect any known future constraints that could result from raw material or component part availability. Manufacturing capabilities are determined through a number of pieces of information. These include:

• Historical manufacturing capacity

• Equipment plans, including new equipment that could increase throughput or scheduled maintenance that could temporarily reduce capacity

• Anticipated labor constraints, in terms of available specialty skills, vacation time, training time, and so on

• Improvement plans beyond equipment plans, such as process improvements that could increase throughput

Logistics capabilities can include any anticipated constraints on either inbound or outbound logistics, including possible transportation or warehousing disruptions. Altogether, these three categories of capabilities (supplier, manufacturing, and logistics) determine the overall capacity forecast for the firm.

After this capacity forecast is determined, it can be matched up against the demand forecast produced during the demand review stage of DSI. This is the critical point—where the firm identifies the kind of gaps described earlier in this chapter. This is also where DSI becomes the mechanism to plan the business. These gaps must be closed: when there is more demand than there is supply, or when there is more supply than there is demand. In some cases, these gaps are fairly straightforward, and solutions are fairly apparent. For example, if excess demand exists for Product A, and simultaneously excess capacity exists for Product B, simply shifting manufacturing capacity from B to A might be possible. The answer might be obvious. However, in other cases, as was described earlier in the chapter, the optimal solution to the demand-supply gap might not be so apparent. In those cases, one must take other perspectives into consideration, which is the reason behind the next step in the DSI process: the reconciliation review.

Reconciliation Review

If a firm were to stop the process with the supply review, described in the preceding section, it would have a perfectly serviceable, albeit tactical, S&OP process. The reconciliation review, along with the executive DSI review, transforms S&OP into DSI, for this is where the process is transformed from one that is designed to plan the supply chain into one that is designed to plan the business. The objective of the reconciliation review is to begin to engage the firm’s senior leadership in applying both financial and strategic criteria to the question of how to balance demand with supply. The reconciliation review focuses on the financial implications of demand-supply balancing, and the meeting is thus typically chaired by the chief financial officer responsible for the line of business being planned. Attendees at this meeting include the demand-side executives (sales, marketing, and line-of-business leaders), and supply-side executives (the supply chain executive team), along with the CFO. Its aim is to have senior financial leadership lead the discussion that resolves any issues that emerged from the demand or supply reviews, and to ensure that all agreed-upon business plans are in alignment with overall firm objectives. At this point the discussions that have taken place in previous steps, which have typically focused on demand and supply of physical units, become “cashed-up.” In other words, the financial implications of the various scenarios that have been discussed in the demand and supply reviews are now considered. Most unresolved issues can be settled at the reconciliation review, although some highly strategic issues might be deferred to the executive DSI review, discussed next.

Executive DSI Review

The executive DSI review is the final critical component of the DSI process, and it constitutes the regularly scheduled (usually monthly) gathering of the leadership team of the organization. The chair of this meeting is typically the CEO of the entity being planned, whether that is the entire firm or an identified division or SBU. The overall objective of the executive DSI meeting is to

• Review business performance

• Resolve any outstanding issues that could not be resolved at the reconciliation meeting

• Ensure alignment of all key business functions

This leadership meeting is where all key functions of the enterprise, from sales to marketing to supply chain to human resources to finance to senior leadership, come together to affirm the output of all the other pieces of the process, and where all functions can agree on the plans that need to be executed for the firm to achieve both its short- and long-term goals. In other words, this is where all functions gather to make sure that everyone is singing out of the same hymnal.

Clearly, for this process to be effective, the right preparation work must be completed before each of the scheduled meetings so that decision-makers have relevant information available to them to guide their decisions. Also, the right people must be present at each of these meetings. Both of these requirements lead directly to our next topic.

Characteristics of Successful DSI Implementations

An old quote, attributed to a variety of people from Sophie Tucker to Mae West to Gertrude Stein, says, “I’ve been rich and I’ve been poor, and rich is better.” In a similar vein, I’ve seen good DSI implementations, and I’ve seen bad ones, and good is better! Based on the good, and bad, that I’ve seen, here are some characteristics of successful DSI implementations:

• Implementation is led by the business unit executive. In other words, DSI cannot be a supply chain–led initiative if it is to be successful. The most common reason for the failure of DSI is lack of engagement from the sales and marketing sides of an enterprise. Often, the impetus for DSI implementation comes from supply chain organizations, because they are often the “victims” of poor integration. Many of the 40+ forecasting and DSI audits that have been conducted by our research team have been initiated by supply chain executives, usually because their inventory levels have risen to unsatisfactory levels. The preliminary culprit is often poor forecasting, which is usually just the tip of the iceberg. Poor Demand/Supply Integration is usually to blame, and it is often due to lack of engagement from the sales and marketing sides of an organization. So DSI implementations absolutely need commitment of time, energy, and resources from sales and marketing, but the front-line personnel who need to do the work are often unconvinced that it should be part of their responsibility. This problem can be most directly overcome by having the DSI implementation be the responsibility of the overall business unit executive, who has responsibility for P&L, and to whom sales and marketing report.

• Leadership, both top and middle management, is fully educated on DSI, and they believe in the benefits and commit to the process. DSI is not just a process consisting of numerous steps and meetings. Rather, it is an organizational culture that values transparency, consensus, and a cross-functional orientation. This organizational culture is shaped and reinforced through the firm’s leadership, and for DSI to be successful, all who are engaged in the process must believe that both middle and top management believe in this integrated approach. Such engagement from leadership is best achieved through education on the benefits of a DSI orientation.

• Accountability for each of the process steps rests with top management. Coordinators are identified and accountable for each step. Obviously, business unit and senior management have other things to do than manage DSI process implementation, so coordinators must be identified who have operational control and accountability for each step. DSI champions must be in place in each business unit, and this should not be a part-time responsibility. Our research has clearly shown that continuous process improvement, as well as operational excellence, requires the presence of a DSI leader who has sufficient organizational “clout” to acquire the human, technical, and cultural resources needed to make DSI work.

• DSI is acknowledged as the process used to run the business, not just run the supply chain. The best strategy for driving this thought process is to win over the finance organization, as well as the CEO, to the benefits of DSI. Without CEO and CFO engagement, DSI can easily be perceived throughout the organization as “supply chain planning.” A huge benefit from establishing DSI as the way the business is run is that it engages sales and marketing. I have observed corporate cultures where DSI is marginalized by sales and marketing as “just supply chain planning, and I don’t need to get involved in supply chain planning. That’s supply chain’s job.” However, if DSI is positioned as “the way we run the business,” then sales and marketing are much more likely to get fully engaged.

• Recognition exists that organizational culture change must be addressed for a DSI implementation to be successful. Several “levers” of culture change must be pulled for DSI to work:

• Values. Everyone involved in the process must embrace the values of transparency, consensus, and cross-functional integration.

• Information and systems. Although IT tools are never the “silver bullet” that can fix cross-functional integration problems, having clean data and common IT platforms can serve as facilitators of culture change.

• Business processes. Having a standardized set of steps that underlie the DSI process is a key to culture change. Without clearly defined business processes, important elements of DSI can be neglected, leading to confusion and lack of integration.

• Organizational structure. Having the right people working in the right organizational structure, with appropriate reporting relationships and accountabilities, is a key facilitator to culture change.

• Metrics. People do that for which they are rewarded. What gets measured gets rewarded, and what gets rewarded gets done. These are clearly principles of human behavior that are relevant to driving organizational culture.

• Competencies. Having the right people in place to do the work, and providing the training needed for them to work effectively, are critical elements to successful DSI implementations.

DSI Summary

The remainder of this book focuses on how best to forecast demand. However, to bring the discussion full circle, the reader is referred to Figure 1-1—Demand/Supply Integration, The Ideal State. This book focuses on the arrow labeled “Demand Forecast.” I strongly believe that without an effective Demand/Supply Integration process, an accurate demand forecast is not worth the paper it’s written on (or the disk space it takes up on a computer system). I also strongly believe that this one arrow represents the critical beginning of the process. World-class DSI processes require world-class demand forecasting, and it is that to which the discussion turns.