Case 17. Tmall, The Sky Cat: A Rocky Road Toward Bringing Buyers and Suppliers Together

† Woodbury University, Burbank, California, USA; [email protected]

‡ Alibaba Group, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China; [email protected]

Company Overview

Jack Ma, a former college English teacher, founded Alibaba Group with 17 friends in his apartment in Hangzhou, China, back in 1999. His original vision was to create a 24/7 “matchmaker” B2B platform where foreign buyers could easily communicate with Chinese suppliers. Within several years the B2B platform Alibaba.com grew significantly. When eBay entered China’s C2C market in 2002, Jack Ma felt the pressure immediately. He knew very well that in China’s e-commerce market, the difference between businesses and individual users was quite subtle (Wang, 2010), since most individual users were also small business owners. Knowing that small and medium enterprises were the main engine of China’s economy, Alibaba established the C2C platform Taobao (which means “searching for treasure” in Mandarin) to compete with eBay for the lucrative market in 2003. Despite skeptics and fierce competition, Jack Ma confidently predicted that Taobao would win the battle, “Ebay may be a shark in the ocean, but I am a crocodile in the Yangtze River. If we fight in the ocean, we lose—but if we fight in the river, we win” (Doebele, 2005).

With a clear understanding of the market, Taobao came with features specific to Chinese users, who at that time were still grasping the idea of e-commerce. Unlike other auction websites that charged transaction fees, Taobao’s no-fee and no-threshold policy let anyone possessing a computer with Internet access to operate on its platform. Its popular “Wang Wang” instant messaging services, together with the free Alipay payment escrow system, allowed buyers to communicate with sellers before placing orders online as well as to control the authorization of payment release until they actually received the items. Users’ satisfaction levels greatly improved. Although a relatively latecomer, Taobao got a quick start with its free listings and took fewer than two years to overtake eBay China, the previous leader in China’s C2C market.

While occupying around 75% of the C2C market share in 2008, Alibaba saw the shortcomings of the popular auction market. Because Taobao and Alipay were both free of charge, the main revenue Taobao generated was from brand advertising and “pay for performance” in its search ranking section. Additionally, fierce competition among sellers made many merchants resort to low prices to attract customers. Taobao became a marketplace flooded with substandard products and counterfeits, and intellectual property infringement issues began to hold back the further growth of the platform.

As Chinese online shoppers’ tastes and expectations grew more sophisticated, the e-commerce market in China also shifted gradually from the C2C model, where items are exchanged between individuals, to the B2C model where customers buy directly from brand owners and authorized distributors (see Exhibit 17-1). Several other e-commerce companies including 360buy.com, operated by Jingdong Century Trading Co, and Joyo Amazon, had already started their B2C operations in China. Adapting to the trend, Alibaba Group launched the B2C platform Taobao Mall in April 2008, assessed through http://mall.taobao.com, as a complement to Taobao’s C2C market, Taobao Marketplace. Positioned to be a virtual shopping mall consisting of internationally known brands and major retailers, Taobao Mall aimed to raise the standards of product quality and the online shopping experience for customers. The initial fee schedules for merchants to join Taobao Mall included an annual membership fee of RMB 6,000 (approximately $940), a compulsory deposit of RMB 10,000 (approximately $1,560) that was refundable if no disputes were filed against the seller, and commissions from each transaction.

Enjoying Taobao’s support, Taobao Mall started with the unrivaled advantage of access to 98 million existing Taobao consumers, and its virtual shopping mall concept quickly captured China’s B2C market. Many brand name merchants tested various promotions on the platform. For example, Mercedes Benz sold 200 Smart cars in about three and half hours during its group-buying campaign on September 9, 2010. Taobao Mall’s transaction volume quadrupled in 2010 from the previous year, including record sales of RMB 936 million (US $141.6 million) on its special “Singles Day” (celebrating people who are still living the single life) promotional event on November 11, 2010.

The Crisis

Compared to Taobao Marketplace, Taobao Mall possessed several advantages in attracting buyers. Merchants were required to be verified and to adhere to the standards established by Tmall that covered core aspects of the online retail process on brand building, product management, customer services, and logistics. Taobao Mall guaranteed product authenticity as well as offering a seven-day no-questions-asked return policy. To increase the traffic on Taobao Mall, the top places of Taobao’s search results were reserved for the Taobao Mall sellers. In addition, Taobao Mall promised punctual delivery of goods through strategic alliances with logistics fulfillment companies. Thus, even though Taobao Mall charged fees while Taobao Marketplace remained free, small business owners still preferred to have their virtual storefronts on Taobao Mall. With the relatively low entrance requirements, many unlicensed merchants took the opportunity to register and operate on the B2C platform. The distinction between the two modes of operation soon became unclear. The difficultness of monitoring product and service quality offered by a large number of small business owners led to numerous consumer complaints, mostly about product quality and authenticity. Several foreign brands started filing lawsuits after setting up their stores on the platform. In July 2011, three Swiss watchmakers, Longines, Omega, and Rado, resorted to litigation by suing Taobao in Beijing for failing to stop the sale of knockoff watches in Taobao Marketplace, demanding Taobao to ban listings of their watches priced at under RMB 7,500 ($1,180) (Bergman, 2011).

In early October 2011, in response to the ubiquity of counterfeit and substandard products sold on Taobao Mall and in an effort to persuade small vendors to return to Taobao Marketplace, Taobao Mall issued a substantially modified new fee schedule that included an up to 10-fold increase in membership fees and 15-fold increase in cash deposits, effective in January 2012 (He & Tang, 2011). The sudden fee increases ignited a storm of online protests named “Taobao October Rising” initiated by close to 50,000 small vendors (Hille, 2011), including some who were previously fined by Taobao for selling fake products. The riots escalated when angry sellers uniformly disrupted Taobao Mall’s operations through simultaneously auctioning products from major retailers, leaving negative feedback, and refusing to pay for the transactions. Several major retailers had to shut down their virtual stores temporarily. There were also thousands of sellers protesting in front of the Alibaba’s headquarters building in Hangzhou, China. China’s Ministry of Commerce publicly urged Taobao Mall to “listen to the opinions of all parties and take proactive measures to respond to the reasonable demands of the relevant merchants, especially small and medium-sized” (Fletcher, 2011).

Alibaba soon responded to the disputes with a revised fee schedule including a 50% reduction in cash deposit and a 9-month grace period for sellers who maintained good ratings (Table 1), as well as an investment plan of RMB 1 billion ($157 million) to make up the shortfalls in cash deposit reduction, RMB 500 million ($78 million) as a guarantee fund to help the small vendors get qualified for bank loans, and RMB 300 million ($47 million) in technical support and promotion.

The Rebranding Process

The rebranding process of Taobao Mall started well before the crisis. As Taobao’s user population increased exponentially, Jack Ma pointed out that its growth would hinder the company’s ability to make decisions quickly, and “we had to separate, make sure they moved faster” (Chao, 2012). Alibaba Group invested heavily on the construction of the Taobao Mall brand to better distinguish itself from the C2C portion of Taobao. In June 2011, Alibaba announced that it had decided to split Taobao into three separate units, Taobao Marketplace, Taobao Mall, and etao, an Internet search engine. Starting November 2011, Taobao Mall was renamed Tmall and began operating under an independent domain, http://www.tmall.com. Taobao explained that the move was meant to differentiate the Tmall brand and “give people a very clear idea that this is the first choice to find high-quality products” (Chao, 2010).

Table 17-1. Tmall’s Fee Schedule

The riots sped up the rebranding process. In January 2012, Alibaba formally changed Tmall’s name in Mandarin to Tian Mao (which means “sky cat”). Two months later, Tmall came out with a new logo, a black cat drawn in the shape of the Chinese character for Sky and the English letter T (see Exhibit 17-2). The design was chosen from a contest that generated approximately 12,000 designs submitted by netizens and professional studios. The cat was inspired by the image of one appearing in ancient artwork that represented taste, wealth, and divinity. As pointed out by Tmall’s President, Daniel Zhang, the ultimate goal of Tmall is “to become the ‘Fifth Avenue’ and ‘Champs-Élysées’ of e-commerce by providing the world’s most fashionable, trendy, and high-quality online shopping experience.” The new advertising campaign stated, “Tmall: the size of eight Fifth Avenues combined.” By October 2012, Tmall has hosted online storefronts for more than 70,000 multinational and Chinese brands from over 50,000 merchants including Adidas, Gap, Mercedes, Nestle, Nike, P&G, Ray-Ban, Unilever, and Uniqlo.

The Future

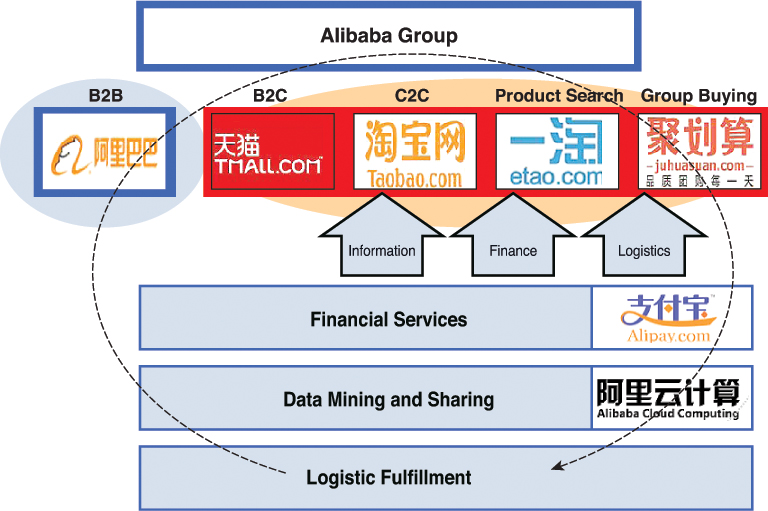

Alibaba Group’s current e-commerce system includes Alibaba.com (B2B), Tmall (B2C), Taobao Marketplace (C2C), etao (product search engine), and Juhuasuan (group buying), supported by its Alipay (online payment platform), Alibaba Cloud Computing (data mining and sharing), and logistic fulfillment services (see Exhibit 17-3).

Although China’s e-commerce market is becoming crowded with many players of various operating models, Tmall continues to be the leader in the B2C segment. It has a profit margin greater than 50%, while most other competitors only have single-digit margins (Chao, 2012). Tmall and Taobao’s Singles Day promotion on November 11 has also become a phenomenon over the last several years. The one-day sales on Tmall alone climbed to RMB 3.36 billion in 2011 ($525 million) and reached to a historical high of RMB 13.2 billion ($2.06 billion) in 2012.

One of the main advantages of Tmall’s operational model is that it minimizes costs and risks by not holding any products itself, while other traditional independent B2C platforms such as Jingdong’s 360buy or Joyo Amazon have full responsibility of the storage and delivery of most goods. However, being just a platform also means that Tmall cannot match the consistency in sales policies and service quality provided by the traditional B2C platforms. Furthermore, Tmall faces toughening competition from traditional brick-and-mortar businesses that recently also introduced their own online shopping sites.

Most importantly, given the digitally savvy but geographically diverse shoppers, China’s infrastructure already feels the pressure of the growing number of parcels flooding in the streets from the e-commerce market. Last year logistics companies complained that Tmall did not share sales information and they were overwhelmed with the sudden increase in parcel delivery requests right after the Singles Day promotion. Although this year Tmall cooperated with nine major logistics partners to prepare for the peak delivery needs, it remains unclear if the estimated 100 million parcels could be delivered on time.

Discussion Questions

1. What are the main strengths and weaknesses of Tmall’s business model?

2. What strategies and actions taken by Alibaba have upset its relationship with small sellers? Were those strategies and actions necessary? Are there any better alternatives Alibaba could consider?

3. Should Tmall continue its Singles Day promotion in the future? What are the main disadvantages of the temporary discounts and their impacts on inventory management?

References

Bergman, Justin (2011). “The eBay of the East: Inside Taobao, China’s online marketplace.” Time, November 2, 2011. Retrieved from www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,2098451,00.html.

Chao, Loretta (2010). “Alibaba gives Taobao Mall retail site more prominence.” Wall Street Journal (Online), November 1, 2012. New York, NY.

Doebele, Justin (2005). “Standing up to a giant.” Forbes, April 25, 2005. Retrieved from http://www.forbes.com/global/2005/0425/030.html/.

Fletcher, Owen (2011). “The new online battleground; For China’s e-commerce sector, the focus shifts to business-to-consumer sites.” Wall Street Journal (Online), October 27, 2011. New York, NY.

Gao, Kane (2012). “Tmall’s new logo, and its amusing heritage.” Illuminant: Public Relations and Strategic Communications. Retrieved from www.illuminantpartners.com/2012/04/09/tmall-logo-amusing-heritage/.

He, Wei and Zhihao Tang (2011). “Taobao Revises Fee Plan.” China Daily, October 18, 2011. Retrieved from http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/bizchina/2011-10/18/content_13921477.htm.

Hille, Kathrin (2011). “Alibaba hit by Internet protest.” Financial Times, Oct 13, 2011. Retrieved from http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/a849c9f8-f59b-11e0-94b1-00144feab49a.html#axzz2L2VcLY2k.

iResearch Consulting Group, China (2012), “Chart 2-1 Revenue of 2008-2015 China Online Shopping Market,” 2011-2012 China Online Shopping Research, May 24, 2012.

Wang, Helen H. (2010). “How eBay failed in China.” Forbes, September 12, 2010. Retrieved from http://www.forbes.com/sites/china/2010/09/12/how-ebay-failed-in-china/.