Chapter 25. Decoupling

“The Great Wall [of China] is evidence of a historical inability of people in this part of the planet to communicate, to confer and jointly determine how best to deploy enormous reserves of human energy and intellect.”

Ryszard Kapuścinśki, in Travels with Herodotus

The recovery started in emerging markets, breaking the decades-old pattern of following the lead of developed markets. The good news is that the bigger emerging markets had indeed “emerged” with strong institutions; the bad news is that their recovery seems to have been won only with unsustainably cheap money in China.

The week after the synchronized crash, Controladora Comercial Mexicana SAB (Comerci), Mexico’s third-largest supermarket chain, filed for bankruptcy. Its Mexican customers were not much worried by the crisis on Wall Street. But Comerci had taken a $1.1 billion loss on currency derivatives it had bought from banks. These protected it against a rise in the peso but exposed it to great losses if the peso went down. As foreign investors desperately reduced their risk and paid down debts, they sold their Mexican investments. In doing so, they sold pesos and bought dollars, inflicting a sudden collapse on the peso. That brought down Comerci, even though it was largely a domestic concern.

This looked like the beginning of a replay of the emerging markets disasters of the 1990s, with an exit of international money leading to a currency crisis and then a debt crisis. Defaults by governments, a true disaster scenario, seemed a real possibility—but did not happen. Instead, emerging markets led the world in a rebound. It is vital to understand how they did this.

Comerci was not alone. Indeed, the spread of the problem showed how indiscriminately international funds had sought out emerging markets. There were losses like this in Brazil, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Poland, and Taiwan. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), as many as 50,000 emerging markets companies lost money on currency hedges, including 10 percent of Indonesia’s exporters and 571 of Korea’s smaller exporters. Losses in Brazil were $28 billion, according to the IMF, while in Indonesia they were $3 billion. Mexico and Poland suffered losses of $5 billion each. Sri Lanka’s publicly owned Ceylon Petroleum Company lost $600 million, and even the huge Chinese bank Citic Pacific lost $2.4 billion.1

The options sold in Korea were known as KIKO (Knock-In, Knock-Out) and protected against a rise in the local currency up to a certain point; at which point they would knock-out, meaning that there was a lid on the protection they offered against a big rise. In the years when the boom in commodities and BRICs pushed emerging market currencies ever upward, this was a great deal. Effectively, companies buying these options from banks had successfully bet that their currency would keep rising. But if the local currency dropped below the rate at which the contracts knocked-in, then the companies were themselves on the hook to compensate the banks who sold them the derivatives. They had effectively let the banks place a bet with them that their currency would fall.

Regulators watched banks’ forex positions closely to avoid a repeat of the Mexican crisis in 2004, when Mexican banks had used swaps to take on foreign exchange risk, but they did not keep the same watchful eye on nonfinancial companies like supermarkets or television manufacturers.

The result nearly turned a crisis into a disaster. In the weeks after Lehman, money poured out of emerging markets, pushing their currencies down, in response to the panic in the West. As emerging markets had been at bubble prices months earlier, many foreigners were still sitting on profits, making them all the more anxious to sell. As they sold bonds, so their yields rose, making it more expensive for companies, or governments, to borrow. When companies ran into forex losses, they had to buy dollars, pushing their own currencies down further.

This painful logic was the exact opposite of “decoupling.” Far from offering some protection, MSCI indexes showed emerging markets dropping by two-thirds in the 12 months after their peak on Halloween 2007. In doing to, they underperformed the developed world, where the roots of their problem lay, by 26 percent.

Fragile systems and institutions were put under pressure for the first time and were found wanting. Russia had to close its two biggest stock exchanges for several days in September 2008, under the weight of orders. The momentum seemed unstoppable.

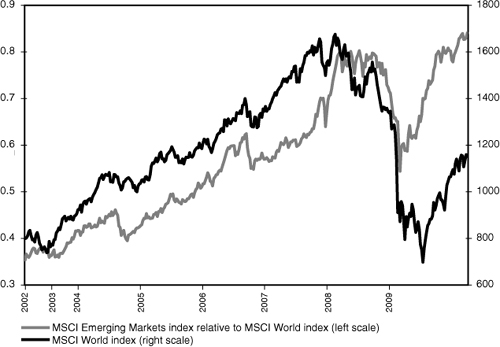

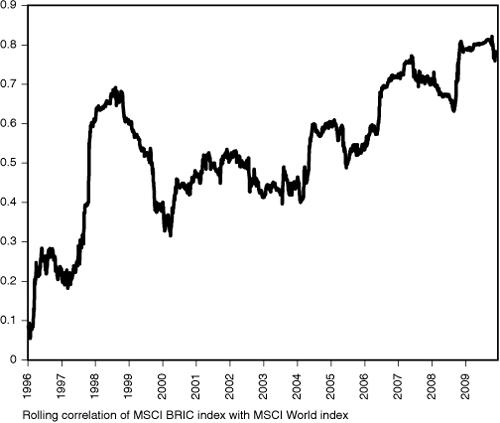

But on October 27, that momentum stopped. Emerging markets stocks stopped, wobbled, and then began a rally, even as fresh panics over the banks saw the developed world markets fall to even worse lows (see Figure 25.1). At least as far as their markets were concerned, the emerging markets had at last “decoupled.” They hit bottom and started to recover before anyone else. The importance of this cannot be overstated; after a generation when emerging markets had merely offered a more extreme version of what was available in the developed world—doing better when times were good and worse when times were bad—they had finally parted company (see Figure 25.2).

Figure 25.1. Decoupling? Emerging markets suddenly and briefly parted company from developed markets in October 2008.

Figure 25.2. The Brics grow more tightly linked to the developed world.

What happened? First, the developed world came up with aid. U.S. policymakers knew that big emerging market defaults would ensure a Depression. So on October 30, the Federal Reserve announced “swap lines” of $30 billion each for Brazil, Mexico, Singapore, and South Korea.2 In English, this meant that they lent dollars to these countries’ central banks, which could in turn lend the dollars to domestic companies who were desperate for cash to pay off dollar-denominated loans. Crucially, they could do this without buying dollars on the open market, which would have pushed the local currencies down further. Trying to avoid moral hazard, the Fed restricted aid to systemically important countries with good financial management. It adroitly headed off the dynamic by which currency devaluations had turned into debt crises in the past.

Second, and more important, in late October news filtered out that China had a stimulus plan for its economy. Chinese economic data is carefully managed, but the figures that are hardest to massage looked alarming. For example, electricity generation was falling, implying that the economy might be contracting. Some basic industries, such as the factories making cheap toys and shoes in the Pearl River Delta near Hong Kong, saw dramatic shutdowns amid complaints from workers that factory owners had absconded with their wages.3

At the very least, there was a real danger that China’s growth would drop below 6 percent per year for the first time since the Tiananmen massacre, 19 years earlier. This would have broken the Communist Party’s longstanding compact with the people that it would maintain fast growth. But China was sitting on a huge war chest in the form of its foreign reserves. The hope was that it would reply with devastating force. It did.

The stimulus package, when announced, came to $586 billion (for a headline number of 4 trillion renminbi) of new government spending in two years, on infrastructure and social welfare projects. It sounded like a New Deal. This was part of an “active” fiscal policy, while monetary policy would be “moderately active”.4 There were concerns over how much money was truly new, but markets’ relief was palpable. The Shanghai Composite rose 7.3 percent the day after the announcement and never looked back. And commodities, once more, lurched on news from China. Copper rose 10 percent in a day.

There is a final reason that emerging markets bounced; unlike the United States and Western Europe, they had learned the lessons from the crises of the 1980s and 1990s. When the KIKO options debacle briefly threatened a new crisis, they showed they were not as vulnerable to the flows of international capital as they used to be. “Markets behaved the way they always do, which is that they misbehaved. They reached the ledge,” said Antoine van Agtmael, who had invented emerging markets as an asset class a quarter of a century earlier. “And then people said: ‘This is ridiculous.’”5

Agtmael used a medical analogy: “Pandemics are dangerous when the immune system is poor. But pandemics are mitigated if the immune system is good. Basically the emerging markets had better immune systems than most people thought.” In other words, they had foreign exchange reserves, their consumers did not have much debt, and their banks were better regulated than before.

Not only China had stockpiled foreign reserves. Russia spent $200 billion in an (unsuccessful) attempt to defend the ruble. South Korea was sitting on $240 billion—far more than the $22 billion with which it had entered its crisis in 1997. And emerging markets were relatively cheap while government cash was available to help buy them. By the end of November 2009, $72.5 billion had flowed into emerging market funds for the year, far exceeding the previous record of $54 billion for the bubble year of 2007. That drove an epic rally. A year after hitting bottom, the emerging markets index had more than doubled, with the BRICs up 145 percent. The strongest stock market in the world over that time, gaining 195 percent, was Peru. This showed a return to self-reinforcing logic. Peru’s fortune was almost entirely a function of China and its appetite for commodities like copper. And at the heart of this logic lay a recovery in China that seemed self-contradictory.6

China’s imports of metals were so prodigious that it was hard to see how they could possibly be used. Its copper imports doubled in the first nine months of the year alone, causing the global copper price to double with it. Much of this appeared to be stockpiling, or speculation,7 but the buying drove revivals for Peru, a big metals exporter, and other commodity-exporting countries.

The speed of the recovery, and the rapacity of China’s appetite, soon generated concern. In November 2008, China had announced a “moderately active” monetary policy. What ensued could more accurately be described as “hyperactive”. Aggregate new lending in the first half of 2009 ran at almost triple its level in the first half of the year before—an almost unfathomably swift expansion, which the Chinese authorities soon tried to rein in. How could such a swift boom in lending not lead to a credit bubble? Unsurprisingly, China’s stock market went into a downturn, echoed elsewhere around the world, as China attempted to rein in its banks in early 2010.

China’s currency adds a dangerous extra element to the mix. During the previous emerging markets bubble, which burst in the summer of 2008, the Chinese currency rose by 20 percent against the dollar in three years—and so Chinese exporters steadily became less competitive. During the rally of 2009, China’s currency stayed pegged to the dollar, so outflows from dollars into countries like Brazil forced up the local currency against both the dollar and the renminbi. The effect was to make both the United States and China more competitive.

That provoked a political reaction, which can only intensify if the renminbi continues to get cheaper. Brazil attempted to curb the inflows in 2008 by imposing a tax on incoming investments in either Brazilian stocks or bonds—a dramatic sign that the foreign cash was now unwelcome. Similarly, Taiwan put limits on holdings of foreigners of Taiwanese bank accounts. So did Indonesia.

Emerging markets themselves passed a critical test in 2008. With only some technical assistance from the Fed, they were strong enough to resist a crisis. This was deeply encouraging. But the investor behavior that followed it was not. If the emerging markets had matured, the investors putting money into them, it became ever more obvious, had not. That is cause for grave concern.

In Summary

• China’s stimulus plan ended the debacle for emerging markets in 2008.

• Emerging market institutions are far stronger than in the 1980s and 1990s.

• The critical question is whether China’s recovery is sustainable.