6. Bad Lenders Drive Out the Good

Residential mortgage lending was previously a very staid business. Lenders meticulously considered the merits of making loans: They obtained careful appraisals, required sizable down payments, and made sure each borrower had a stable job and reliable income. Lenders knew their institutions would take substantial financial hits if borrowers failed to make good on their loans. They also knew regulators were watching, checking to make sure each loan was sound.

Staid was the last thing you could call mortgage lending during the housing boom. Frenzied might be a better term—and as the boom became a bubble, out of control would be even more appropriate. The mortgage business had been completely transformed. Lenders now made their money solely on volume; the more loans they originated, the greater their profits. Whether borrowers would be reliable payers was, at best, a secondary concern; Wall Street was buying the loans and, it was thought, using its financial alchemy to ensure that everyone made out. Regulators still cared, but they took comfort in the fact that the lenders they oversaw weren’t on the hook if things turned out badly. The institutions most exposed were unregulated private mortgage lenders and investment banks, ranging from New Century Financial to Bear Stearns. And although they were growing in size and number, they weren’t the regulators’ responsibility.

Wall Street drove the changes in the mortgage-lending business. Making a loan and maintaining ownership of it was no longer as profitable as making the loan and selling it to an investment bank. The investment banks had connections to yield-hungry investors all over the world who were willing to pay fat premiums for anything lenders could originate.

Lenders obliged en masse. They had been making subprime loans for some time, but these originally required large down payments and careful scrutiny of subprime borrowers’ income and savings. Lenders also demanded compensation for the extra risk of making a subprime loan; under the so-called “risk-based pricing” model, the greater the chance of default, the higher the interest rate and the bigger the fees a borrower would need to pay. However, as the market heated up, down payment requirements shrank and documenting a borrower’s income slid from a requirement to a recommendation. Risks were rising, but in the hypercompetitive environment, interest rates and fees could not.

Lenders let their standards slip because if they didn’t make a loan, their competitors would. No industry had more avidly embraced the Internet than mortgage lending, and the effect had been intoxicating for both consumers and lenders. Borrowers previously had few choices; if they needed a loan to buy a house, they could apply at their neighborhood bank branch. Now a horde of eager prospective lenders was only a mouse click or two away. The Internet was a boon for lenders as well, offering any storefront or basement-based operation access to customers across the country, and dramatically cutting the overhead costs involved in making loans. But the net effect was a competitive frenzy, with lenders furiously undercutting each other to gain customers. Everyone, it seemed, was in the mortgage business. Alongside traditional banks and thrifts were largely unregulated real estate investment trusts, Wall Street investment banks, and even home builders trying to move their unsold units. In this atmosphere, a lender demanding strict, old-fashioned credit standards would soon be out of business.

A few old-time mortgage lenders worried that the tried-and-true rules were being abandoned, but most were swept up in the hubris of the time. The housing boom was built on a solid foundation, or so they reasoned. Loans with no down payment were a problem only if housing prices weren’t rising, and prices were rising rapidly. Certainly, they would eventually slow down and level off, but no one expected prices to actually decline. And the lenders’ math-whiz consultants had devised new, sophisticated models of borrower behavior. Applying their algorithms and formulas to past performance, they were confident they could separate the good borrowers from the deadbeats.

As the housing bubble expanded, mortgage lending moved from merely aggressive to increasingly reckless and, in some cases, disingenuous and predatory. On TV, over the Internet, and through the mail, lenders hawked an array of loans with questionable-sounding names: “stated-income,” “piggy-back,” “interest-only,” “pay-option,” and “negative amortization” loans. All were designed to squeeze borrowers with sketchy incomes and no down payment money into homes they couldn’t afford, except under the very best of circumstances. Much of this seemed obvious in retrospect: For example, the ubiquitous so-called “2-28” subprime ARM loan was financially tenable only if a borrower could count on refinancing before the two-year fixed-rate term of the loan expired and the monthly payments shot up. And even if they could refinance in time, borrowers were nailed with a hefty penalty for paying off the loan early.

Mortgage Monkey Business

Given the financial stakes involved, getting a mortgage was surprisingly easy. During the mid-2000s, all it took was a visit to the local bank branch or mortgage broker, either of which a borrower could find in the nearest strip mall. The process took only a short time—the loan officer did a few calculations, pulled a credit report, and requested some additional financial information. When the deal closed, the borrower needed to sign a handful of documents, and the money and property title were transferred.

All this is a breeze when times are good and credit is easy, but even when things tighten up, such as in the current period, the mortgage-lending business is very efficient. It has to be; profit margins are paper thin and volume is necessary to make any kind of money. With thousands of brokers working on commission, they needed to make a lot of loans to earn a good living.

For a home buyer seeking a loan, the most important contact was often either a mortgage banker or a mortgage broker. These professionals’ jobs involve examining the borrower’s financial situation, working out the math to determine the appropriate size and type of loan, collecting the relevant documents, and securing the funds necessary to make the loan. Similar to independent insurance agents, who provide a broader distribution channel for the large insurance carriers, mortgage bankers and brokers provide a service for the big financial institutions with the cash to originate loans.

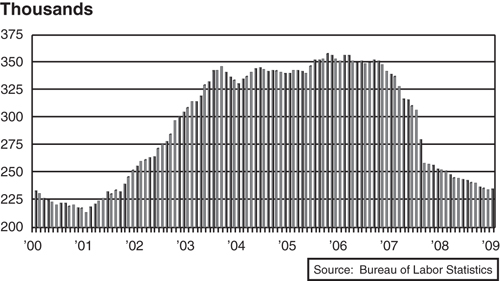

Mortgage banks and brokerages are generally small businesses; at the peak of the housing boom, 75,000 of them were scattered across the country, employing 350,000 workers (see Figure 6.1). They are low-cost operations that often appear and disappear quickly, depending on origination volumes and business conditions in a particular region. Their competitive advantage is choice; they offer borrowers a variety of potential deals, from government-backed loans to those offered by major depository institutions.1

Figure 6.1 Mortgage banking booms: employment in mortgage banking/brokerage.

Mortgage bankers and brokers had historically been lightly regulated; states set the rules that applied to them, which varied substantially across the country.2 This enabled these originators to become major players in subprime lending; during the housing boom, they accounted for more than half of subprime lending. But after a mortgage deal closed, the broker’s role ended. Only if homeowners came back to refinance or buy another home would they ever encounter a broker twice—assuming that the same broker was still in business.

Most borrowers never meet the other professionals involved in making and managing their loans. These include appraisers, inspectors, and title agents—people who are supposed to make sure the house being purchased is worth its agreed-upon price. Mortgage underwriters evaluate the lender’s risk in making a loan. The underwriters’ models compare information about a borrower to details about others in similar circumstances, to determine the chance that a loan will be paid back regularly and on time. Mortgage insurers provide a backup in case the models are wrong and the borrower defaults. Mortgage servicers collect monthly payments and pass along the proceeds to the owners of a mortgage, and they are also responsible for working with borrowers who are struggling to make their payments.

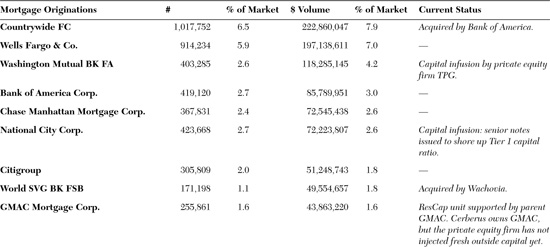

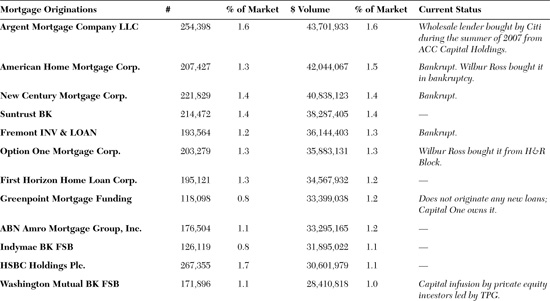

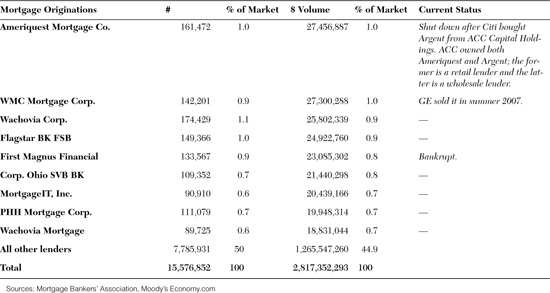

The financial institutions that put up the funds for home buyers—banks or primarily unregulated financial companies—are very large. During the peak of the housing boom in 2005, the nation’s 30 largest institutions accounted for half of all the loans originated (see Table 6.1). Countrywide topped the list, originating more than one million loans worth almost a quarter-trillion dollars that year.3

Table 6.1 Top Mortgage Lenders at the Peak of the Housing Boom in 2005

These institutions aren’t necessarily the ultimate owners of the mortgage loan. Owners include depositories—a commercial bank or savings and loan—or an investor who bought an interest in the loan via a mortgage-backed security. Investors can reside anywhere in the world and might be an individual or an institution—a pension fund, hedge fund, investment bank, or any of the other players in the global capital markets. Depositories own about half of all residential mortgage loans, and investors own the other half. Whoever or whatever they are, mortgage owners are often far removed from the mortgage-making process. They’ve never met the brokers who originated the loans they own, and they will meet the loan servicer only if a loan goes bad and the party at the other end of the chain—the borrower—stops making monthly payments.

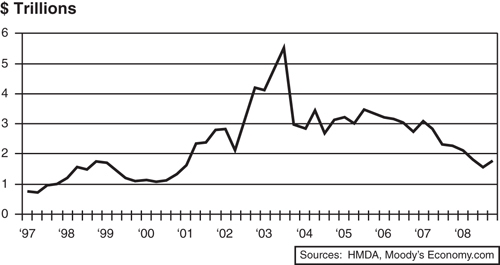

The housing boom was a heady time for the mortgage business. The entire industry—from brokers to servicers—was humming, with many mortgage professionals working long hours, nights, and weekends. The volumes were astounding; between 2004 and 2006, more than $9 trillion in loans was originated, accounting for half of all U.S. first mortgages in effect in 2008 (see Figure 6.2).

Figure 6.2 Mortgage lending soars: mortgage originations.

With soaring volumes came soaring profits, but the mortgage business remained fiercely competitive and margins remained thin. Lenders were driven to keep volumes up and the cash coming in—and they became increasingly creative in finding ways to put households with shaky finances into homes.

Gresham’s Law at Work

Starting a mortgage brokerage firm in the early 2000s was easy; there were few barriers to entry and even fewer to shutting down and leaving the business. Brokerages appeared quickly whenever home buying picked up, and they vanished just as quickly when activity cooled. Costs were low: office rent, a few desks and computers, and some commissioned agents. Relationships with real estate agents and home builders helped but weren’t necessary for success. The key was offering the best interest rate, the lowest origination fees, and—particularly during the housing boom—the easiest loan terms.

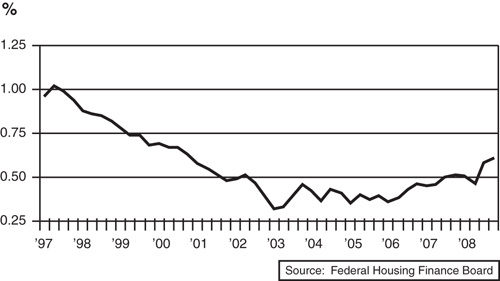

But gaining a competitive edge just by offering low interest rates and origination fees grew difficult early in the decade. Rates were already about as low as they had ever been, and lenders were offering rates not much higher than their own cost of funds—in effect, offering borrowers the wholesale price of money. Fees and points on mortgage loans—what lenders charge for their costs and their time—had also fallen sharply. The average fee on a mortgage loan in the midst of the housing boom was 0.35% of the loan amount—a rock-bottom rate.4 Only a decade earlier, such fees had amounted to more than a percentage point (see Figure 6.3).

Figure 6.3 Mortgage fees plunge: average fees and points on a mortgage loan.

The mortgage industry’s quick adoption of the Internet also pumped up competition during this period. The Web seemed custom-built for a business that had been drowning in documents—simply managing it all had required a substantial back-office bureaucracy to review, organize, and file. With the Internet, obtaining needed information from a credit bureau, appraiser, or title company required only a few clicks.

The Internet also empowered consumers; home buyers could now shop for the best or cheapest mortgages. The local neighborhood bank was no longer the only effective choice. Lenders saw an enormous opportunity to reach borrowers in far-flung places; beginning in the late 1990s, lenders poured resources into developing Web sites and other Internet-based marketing tools. As it happened, Congress had just recently given lenders the legal go-ahead to seek customers nationwide.5 With the growth of online marketing, borrowers could immediately match up offers from lenders across the country and see how tweaking their own financial information—the size of their down payment, the credit score, and so on—affected the interest rates and terms available.

Borrowers were becoming much savvier loan shoppers for other reasons. Tens of millions of homeowners had refinanced their loans at least once to take advantage of the period’s falling interest rates, and they had gained an understanding of the lending process.6 They were much more willing to challenge lenders’ origination fees and to move on to the next lender if they weren’t satisfied.

Barriers to competition were also being ripped down as cheap (low-interest-rate) money became available to lenders of all stripes. Previously, depositors in commercial banks and savings and loans provided the only source of funds to make mortgage loans. However, as Wall Street figured out how to securitize loans, funds began coming in from all corners of the globe, and having deposits was no longer an advantage. Moreover, the investment bankers who sliced, packaged, and sold mortgage loans to investors wanted a full pipeline; the more lenders were out there signing up borrowers, the more there was to securitize. In fact, some investment banks grew frustrated that they couldn’t get enough and began setting up their own mortgage-lending subsidiaries. Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers, Credit Suisse, and others quickly became among the industry’s most aggressive lenders.

Competition was also taking new forms. Mortgage-lending companies were being set up not as traditional depositories or brokers, but as real estate investment trusts (REITs). In the 1990s, REITs became the favored corporate form for developers as a way of avoiding corporate income taxes. Technically, all REIT profits were paid out to shareholders, who then paid personal taxes on them.7 But REITs also avoided the watchful eyes of bank regulators; because they were publicly traded, they fell under the umbrella of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The SEC regulates the stock market, with its main focus on issues such as insider trading and corporate transparency—not the ins and outs of mortgage lending. Mortgage-lending REITs fell through the regulatory cracks, and their sponsors took full advantage of the status. Some of the most egregious, aggressive, and ultimately failed players in the housing bubble were REITs, including American Home Mortgage, New Century Financial, and NovaStar.

As the Federal Reserve slowly raised interest rates between summer 2004 and summer 2006, competition among lenders boiled over. To keep generating new mortgages, even as higher rates made homes less affordable, lenders had to lower their underwriting standards. The REITs and investment banks led the way. A form of Gresham’s law took hold, in which the most aggressive lenders forced the rest—even the more cautious among them—to either lower their standards or lose their market share.8 Lenders could keep going only by making loans on terms they would have considered unimaginable only a few months earlier. The bad lenders were driving out the good ones, as even well-established, conservative lenders gave in to the pressure.

Policymakers Change the Rules

The nation’s financial policymakers encouraged both the burgeoning competition in the mortgage industry and the rapid expansion in lending that resulted. Officials’ motivations ranged from altruistic to crassly political. For both ideological and partisan reasons, the Bush Administration had long disdained government-supported mortgage lenders such as the FHA, Fannie Mae, and Freddie Mac. These institutions had been plagued by management problems and accounting irregularities. In the case of Fannie and Freddie, even the Federal Reserve Board thought they were too large and insufficiently capitalized. The administration believed that the private market could provide all the mortgages Americans needed, more efficiently and at less cost than government-sponsored lenders.

With administration support, regulators began putting fetters on the government-related lenders just as they were easing up on private lenders—at precisely the moment when regulatory oversight was most needed. Even under normal circumstances, regulators have a difficult time encouraging lenders to be prudent. When times are flush and borrowers are paying on their loans, lenders resist any suggestion that they might be overdoing it—extending too much credit and not properly accounting for the risks. But this is precisely when lenders tend to make mistakes and, therefore, when regulators need to be most vigilant. But cracking down wasn’t a politically popular idea during the housing boom; many legislators and the White House were looking for less oversight, not more.

Model Hubris

If mortgage lenders were nervous about their falling loan standards, they could always take confidence in their models. Lenders believed deeply that, whatever their guts told them, their statistically based, computer-driven models could reliably determine whom they should lend to, what kinds of loans they could offer, and how much interest they should charge. The models were brilliant; using the available information on the borrower and the property, they would forecast the odds of the borrower paying regularly and on time. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac had long been champions of these so-called automated underwriting (AU) models, and now other lenders became converts as well.9 Lenders felt sure that their AU models could accurately judge a borrower’s creditworthiness.10

One essential input into every lender’s model is a borrower’s credit score.11 This is a number, typically ranging from 300 to 850, indicating the risk that a borrower will eventually face a credit problem. The lower the score, the more problem-prone the borrower is. A score below 620 generally marks a borrower as subprime. Scores are constructed from credit files—information that lenders report regularly to credit bureaus. Scores reflect not only past payment history, but also how a person uses credit. For example, the more credit cards in your wallet and the closer you are to your credit limits, the greater the risk is of lending you more money and, therefore, the lower your score.

Another essential input into all mortgage-lender models is the value of the house being purchased. Lenders use old-fashioned appraisals, but they also rely on so-called automated valuation models (AVMs) for this. An AVM is automated because it doesn’t require an actual human being to look at the property; instead, it uses statistics and computing power to estimate a home’s value: recent sales of comparable homes, tax assessments, other characteristics of the property, and price trends in the immediate area. AVMs are much less costly than human appraisals and require no waiting for an appraiser to visit a home.

Lenders had little choice but to believe in their models during the housing boom. Loan applications were coming thick and fast; without models that could spit out answers instantaneously, the applications couldn’t be processed quickly enough to meet the competition among lenders. Automated underwriting models, credit scores, and AVM-produced house values are, in most circumstances, effective and promising tools, but lenders were much too comfortable with the results and had come to totally rely on them.

Models are only as good as the information that goes into them, and by 2007, the information going into many models was increasingly suspect. Borrowers had figured out how to manipulate their own credit scores, not by improving their habits, but by making a few simple adjustments in how they managed their debts. For instance, some borrowers paid a fee to be added as an “authorized user” on the credit card accounts of people with higher scores. The positive payment information from the good cardholder improved the additional user’s credit score. Such transplanting of credit DNA wasn’t widespread, but it shows how borrowers were able to game the system and affect lenders’ models.12

Another serious problem with AVMs was that they could fall significantly behind market conditions, particularly at times when those conditions were changing rapidly. For months after housing prices began to bust, AVMs were still showing values that reflected a much stronger market. Lenders were making decisions as if the good times were still rolling, long after they had ended. AVMs also had trouble capturing the real prices being paid for homes at a time when sellers were offering back-door discounts in the form of seller financing or other nonprice concessions. Such off-the-books discounting became common as housing markets weakened; sellers were offering to fix decks or repave driveways to close a sale instead of dropping their official prices. (In fact, a weakness of automated valuations is that they can’t quantify all the small and intangible characteristics that determine a home’s market value. A model might capture the price of a pool or built-out basement, but not the value of the view from the front porch or a troublesome neighbor.)

Lenders’ models depend fundamentally on the premise that history is an accurate guide to the future. Most times this is a reasonable assumption and models will predict the behavior of borrowers reasonably accurately. But at times—such as during the housing boom—conditions don’t match anything experienced historically, and then the models no longer work. In the housing boom, lenders failed to recognize this. Their belief in the predictive prowess of their models emboldened many of them to throw aside philosophical concerns and make what proved to be colossally bad decisions.

The quality of lenders’ underwriting inexorably eroded. At its most crazed point at the apex of the housing bubble, disingenuous, predatory, and even fraudulent lending corrupted significant parts of the mortgage market. The mortgage industry’s dramatic transformation from a staid business to a financial Wild West created the fodder for the subprime financial shock.