11. Credit Crunch

Watching a financial crisis feels much like watching a natural disaster—as long as you’re watching from a safe distance. The raw, uncontrollable power of each is riveting. Although one is made by man and the other isn’t, there is something deeply mysterious about each; it isn’t quite clear how, or why, or why now. Of course, each can create enormous damage and can be heartbreaking for those directly involved. The repercussions last well beyond the immediate shock; nearly everyone is affected at least indirectly, and each leaves scars that never entirely disappear.

The subprime shock was as serious a financial earthquake as any the nation had seen since the 1929 stock market crash.1 There have been some big financial calamities through the years: the collapse of Penn Square Bank in 1982, the savings and loan crisis of the late 1980s, the collapse of hedge fund Long Term Capital Management in 1998, and the Internet stock bust at the turn of the millennium, to name a few. On the financial Richter scale, these other crises might rate a 5 or 6. The subprime shock was off the scale.

This was evident in the size of the losses suffered by global investors. Although the ultimate cost wouldn’t be known for years, most reasonable estimates put the tab close to $2.4 trillion.2 This includes both losses on thousands of defaulting mortgages and the decline in value of the securities backed by other shaky loans. By comparison, the S&L crisis cost the country a mere $250 billion.3 Even Japan’s banking crisis of the 1990s, from which the economy has never fully recovered, doesn’t measure up; its losses come in near $750 billion.

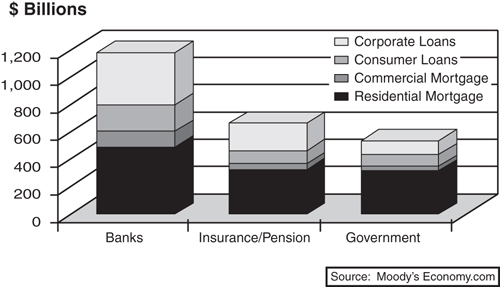

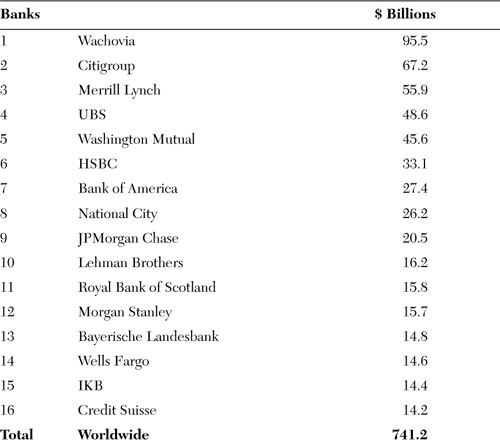

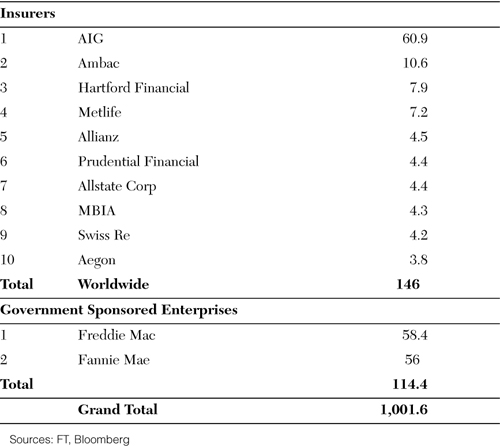

Nearly every sector of the financial system has taken a bath because of the subprime shock. Global banks have lost an estimated $1.2 trillion, insurance companies and pension funds another $650 billion, and hedge funds and all other institutions $550 billion (see Figure 11.1). All kinds of institutions saw their residential mortgage and mortgage security holdings hammered by more than $1.1 trillion—no surprise there—but the extent of their other losses was startling. There were write-downs on commercial mortgage holdings and on business loans and credit of all types; even consumer loans such as credit cards, auto loans, and student loans suffered big losses.

Figure 11.1 Financial sector losses mount: projected losses.

Every corner of the financial system was shaken. Trading in private residential mortgage securities came to a standstill, along with the markets for collateralized debt obligations backed by asset-backed securities and for commercial mortgage securities. Low-rated “junk” corporate bonds and bonds backed by credit card loans were still issued, but investors now held out for a much higher interest rate before parting with their cash. Even the market for municipal bonds, where state and local governments raise money to build schools or sewers, was thrown into turmoil. It wasn’t that municipal or state governments were suddenly likely to renege on their obligations, but in panicked times, every deal seemed suspect.

The subprime shock was also noteworthy for its length. There were tremors beginning in early 2007, when the Chinese stock market swooned, but the shock struck hard in July 2007 and was still reverberating nearly two years later. There were moments when the crisis seemed to ebb, but financial markets remained unsettled throughout. Historically, financial market crises begin and quickly abate in just a few days or weeks. Almost none last more than a few months.

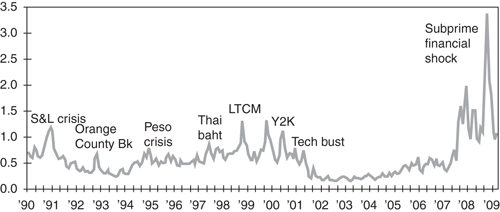

The persistent angst that pervaded financial markets during the subprime shock was clearest in the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) market, where the globe’s biggest banks lend each other money for short lengths of time. LIBOR is particularly important because so many other types of loans are pegged to it. For example, most subprime adjustable-rate mortgages carry interest rates tied to the six-month LIBOR rate. Generally, LIBOR rates are not much higher than rates on U.S. Treasury securities of similar maturity. Treasuries are universally viewed as risk-free, and in normal times, big banks don’t see much risk in lending to each other, either. When LIBOR rates rise significantly above comparable Treasury rates, it’s a signal that bankers are nervous about doing business with each other and want higher rates to compensate for the extra risk. When Long-Term Capital Management collapsed in the late 1990s, for example, the three-month LIBOR jumped to more than a percentage point above the rate on three-month Treasury bills (see Figure 11.2). There it remained for nearly a month. There was a similar increase in the LIBOR–Treasury rate spread in the early 1990s S&L crisis that lasted about three months. In the subprime financial shock, the rate spread sky-rocketed by more than 4 percentage points at its apex in late 2008 and has remained wider than a percentage point for nearly two years.

Figure 11.2 In a league of its own: difference between 3-month LIBOR and Treasury bill yields.

But the most alarming feature of the subprime financial shock remains the fact that it was triggered by U.S. homeowners. Fifty-one million American homeowners have first mortgages, and in a normal year, only about three-quarters of a million of them stop making their mortgage payments and default. In 2006, defaults reached an annual rate of almost 1 million. They rose to nearly 1.5 million in 2007 and more than 3 million by year-end 2008. This was a calamity for those losing their homes and also for the banks and mortgage security investors who owned their mortgages. Conservatively estimated, all those defaults would cost mortgage owners more than $1.1 trillion.4

Even at that size, it is still difficult to see how mortgages could have been the catalyst for such a wrenching financial crisis. In fact, $1 trillion in mortgage losses equals not quite 10% of the $11 trillion in total U.S. mortgage loans outstanding, and that’s not even a meaningful percentage of the $140 trillion in loans and debt securities held by banks, insurance companies, pension funds, hedge and mutual funds, sovereign wealth funds, and other institutions around the world.5 How could the entire global financial system be undermined by subprime mortgage loans?

Reevaluating Risk

It wasn’t the mortgage losses, per se, that ignited the shock, but what they meant more broadly: Global investors had taken on too much risk, not simply in their subprime mortgage security holdings, but arguably in all their investments. The mortgage losses crystallized what had long been troubling to many in the financial markets: Namely, that assets of all kinds were overvalued, from Chinese stocks to Las Vegas condominiums, to the British government bonds known as “gilts” (short for gilt-edged securities). The subprime meltdown was simply a catalyst for a top-to-bottom reevaluation of risk: Were investors being adequately compensated for the risks they were taking? Many quickly concluded that the answer was no.

Global investors suddenly saw the entire U.S. housing and mortgage market in a new light. Although the number of homeowners struggling with mortgage payments was relatively small—only a few million—investors began to question the ability or willingness of all 52 million U.S. mortgage borrowers—subprime, alt-A, and even prime—to meet their obligations. The $11 trillion in U.S. residential mortgage debt outstanding had become a significant global financial influence, accounting for more than 8% of all the bank loans and securities in the world. In short, the world had made a huge bet on U.S. homeowners. In the mid-1990s, few overseas investors had ventured into the U.S. mortgage securities market. Those who did owned mostly debt backed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which was not much different than owning a U.S. Treasury bond. A decade later, foreign investors held some $3 trillion in mortgage securities, almost one-third of all their U.S. financial holdings, including stocks. Some of this was backed by the U.S. government, but most was supported simply by the financial rectitude of the U.S. homeowner. This was seen as safe: Investing in an American household with a home and a mortgage wasn’t supposed to cost investors any sleep—much less their shirts.

Investors also began looking critically at their other holdings, such as corporate bonds. It wasn’t that businesses were defaulting on their obligations; the economy was still strong at the time. The problem was that investors were receiving returns that suggested no firm would ever default again. The rates were razor-thin compared to the potential risks. The difference between rates on risk-free Treasury bonds and rates on low-rated or junk corporate bonds narrowed to an all-time low in spring 2007 (see Figure 11.3). This interest rate difference—the spread—measures how much compensation investors receive for the risks they take with their money. Not only was there not much of a spread in the prices of corporate bonds, but many bonds came with terms considered remarkably loose by historic standards. Traditionally, firms that issue bonds have to meet strict conditions, maintaining a certain level of cash flow or other financial benchmarks, to assure investors that they can meet their interest payments. If the benchmarks aren’t met, creditors have the right to demand their principal back. But in the 2000s, investors were so eager to throw their money around that many bought so-called “covenant-lite” bonds, which had fewer conditions and benchmarks for issuers. Terms became so easy that some businesses were allowed to make interest payments on their bonds by issuing additional bonds instead of paying in cash.6

Figure 11.3 Junk spreads hit lows prior to shock: interest rate difference spread between junk corporate bonds and treasuries.

With corporate bond rates so low and terms so lax, it was incredibly cheap for private equity firms to finance their purchases of public companies. Firms such as the Carlyle Group, Blackstone, Cerberus, and Apollo Management were borrowing this cheap debt to buy out stockholders and take companies private. The plan was typically to reorganize a business, hopefully making it more profitable in the process, and later take it public again at a much higher price. Buyouts often worked purely because it cost so little to borrow in the bond market. To be more precise, private equity firms financed their purchases with bank loans that were then paid off after the bought-out business issued their junk bonds.7 The bank loans were intended to be short-term bridge loans. These deals were all the rage in the lead-up to the subprime financial shock, and they helped drive global stock markets to record highs as private equity firms bid up stock prices.

The subprime meltdown brought it all to a swift end. Investors no longer wanted to buy corporate bonds with interest rates that effectively assumed there would never be another default. They had good reason: Such an assumption couldn’t be right. Publicly traded automakers, retailers, and media companies were being taken private using a lot of debt. These were cyclical businesses—sales rise and fall, as do profits and the cash flow needed for interest payments. Some of these companies wouldn’t make it and would default. Investors lost interest in some deals entirely; for others, they wanted more compensation in the form of higher interest rates. The private-equity buyout mania fizzled, junk bond issuance fell off, and the spread between junk bonds and Treasury rates soared. By late 2008, the yield spread was more than 20 percentage points. Investors were now expecting corporate bond default rates to approach those last seen in the Great Depression.

Investors were also nervous about their holdings of commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS). As with a residential mortgage security, a CMBS is backed by interest and principal payments on mortgages—but these are mortgages on office, retail, and industrial buildings, as well as hotels and apartments. Similar to the residential mortgage securities market, the CMBS market had expanded rapidly prior to the subprime shock as investors willingly purchased securities at increasingly narrow rate spreads. The CMBS market became a huge source of cheap cash for commercial property owners, who aggressively bought up office towers and strip malls. Property prices surged, encouraging even more borrowing in the CMBS market—backed, of course, by the higher-priced properties.

It sounded all too familiar to investors. If the residential securities market was unraveling, CMBS couldn’t be too far behind. CMBS issuance came to a standstill, and the yield spread between CMBS and Treasury bonds widened sharply. Even though commercial property markets weren’t choking on empty space and rent growth was still holding up in most areas, investors weren’t willing to make fine distinctions between the commercial real estate market and the housing market. Commercial property prices were too high, vacancy rates were just beginning to rise, rent growth was sure to weaken significantly, and investors wanted compensation for the risk.

The new attitude toward risk rolled through other global financial markets, affecting everything from emerging debt–bonds issued by developing nations such as Argentina and Turkey; to asset-backed securities, based on credit cards, auto loans, and student loans; to municipal bonds. Although the impact on these markets wasn’t quite as harsh as in the junk bond or CMBS markets, fewer new bonds of any type were issued, and interest rate spreads widened across the entire credit market.

When Insurers Need Insurance

Not all investors had been reckless. Some had limited their purchases of mortgage securities to the top-rated Aaa tranches, and to be even more conservative, they had also purchased insurance. The insurance came from financial guarantors, also known as monoline insurers. These firms had traditionally insured municipal bonds against default; now they were also insuring the highly rated tranches of mortgage securities. The guarantors themselves were rated by the credit-rating agencies—guarantors had promised to make investors whole if anything went wrong with their bonds, so it was important that they be rock-solid Aaa firms. Yet after the subprime shock, the guarantors began to appear markedly less solid than their ratings had indicated. Monolines weren’t failing to make payments on defaulting bonds, but with the pace of defaults soaring, it looked increasingly likely that some might not be able to meet their commitments in the future. As the mortgage securities they had insured were downgraded, odds increased that the guarantors would eventually have to make big payouts—bigger than their executives, investors, or clients had ever imagined would be necessary.

The rating agencies warned the guarantors to raise more capital or risk losing their Aaa rating. It was a potent threat: Without that super-safe rating, the guarantors would be out of business and their insurance meaningless. No investor would trust them to be able to make payouts if needed. Most guarantors took the warning to heart and raised more capital. This wasn’t easy or cheap because potential investors knew there was a reasonable chance the insurance firms might not survive. Nevertheless, the two biggest monolines, MBIA and Ambac, held on tenuously to their Aaa ratings.

The guarantors’ problems exacerbated the nervousness in financial markets. A chain of events that had once seemed unimaginable suddenly began to loom as a possibility. It would work like this: Many large institutional investors, such as pension funds and insurance companies, are barred by law or their own rules from buying any securities rated less than Aaa. Without bond insurance, many securities would lose their Aaa ratings; thus, pension funds and insurance companies would be forced to sell them. If a guarantor went out of business—or even lost its own Aaa rating—the securities it had insured could suddenly face such a downgrade. As the monolines’ problems grew, so did the odds they would lose their Aaa ratings. The prospect of institutional investors suddenly flooding the markets with massive amounts of bonds began to haunt financial players.

Such worries reinforced the free-fall in mortgage securities and also pushed the formerly staid municipal bond market into turmoil. Perfectly solvent state and local governments and authorities found themselves having to pay interest rates reserved for high-risk borrowers. This was most clearly demonstrated by the disruption of the auction-rate securities market. In this out-of-the-way market, certain long-term municipal bonds were treated as if they were short-term investments, with interest rates set once a week in an auction run by large Wall Street investment banks. The rates were typically lower than for comparable fixed-rate bonds, making them attractive to municipalities issuing debt. The weekly auctions effectively turned long-term municipal bonds into more liquid short-term bonds, which appealed to investors such as money market funds. Both features, however, depended on the success of the weekly auctions. So important were these auctions that, to ensure their smooth functioning, the investment banks would step in and buy the debt themselves if they failed to attract enough outside bidders.

In early 2008, spooked by the potential failure of the monolines and other worries, investors stopped participating in the auctions, causing scores of them to fail. Even the investment bank sponsors, worried about their own financial exposure, refused to play their usual backstop role. As a result, the interest rates on auction-rate securities surged. Municipalities were suddenly forced to pay rates far higher than even junk corporate borrowers. Trust had broken down so thoroughly that municipalities couldn’t even count on their own investment bankers. The subprime financial shock had engulfed even state and local governments.

Leverage and Liquidity

If the subprime shock involved no more than a massive reevaluation of risk, it still would have been a garden-variety financial event and not a global crisis. Investors took a hit, but this was seen early on as a healthy antidote to the housing bubble. Risk-taking had gotten out of control; financial decisions made less and less economic sense. For instance, the private-equity firm Cerberus’s leveraged buyout of the Chrysler Corporation, which involved piling a lot of debt onto the balance sheet of a very cyclical vehicle manufacturer struggling to sell big cars in the face of steadily rising gasoline prices, might be a case in point. Officials at the Federal Reserve and other central bankers weren’t unhappy to see such excesses being wrung out of the financial system.

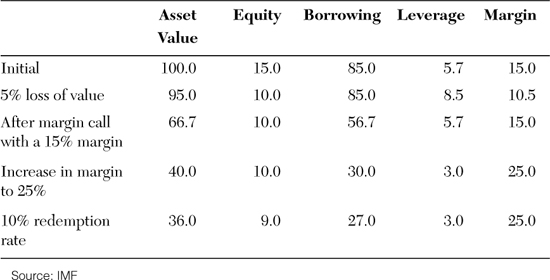

Views quickly changed as the shock’s nasty side came into clearer relief. As the shock wore on and losses mounted, investors who borrowed money to pump up their returns in the good times came under increasing pressure to reduce their leverage. As this process of deleveraging gained momentum, the subprime financial shock turned from a therapeutic to a destructive process. To see the corrosive, self-reinforcing nature of financial leverage, consider the hypothetical example of an investment fund that bought mortgage securities by borrowing 85% of the purchase price, using its own equity for only 15% (see Table 11.1). The fund’s leverage can be expressed as 85/15, meaning that the power of its own investment has been magnified 5.7 times by leverage. Now suppose that the securities the fund owns fall in value by 5%. This isn’t a very large decline, but it reduces the fund’s equity to 10%, and its leverage jumps to 85/10 or 10.5 times. Because the fund agreed when it borrowed money from a broker-dealer to maintain at least 15% equity, it receives a notice known as a margin call, requiring it to either put up more cash or sell as much of the portfolio as necessary to get back to the agreed margin. Most funds are reluctant to put up more cash, particularly in a declining market, so they take the second option and sell. Brokers, meanwhile, can demand higher margins; if they believe the value of the underlying collateral is eroding, they might decide that the original 15% is too low. If in this example the broker increases the margin to 25%, the funds have even more selling to do. Things get measurably worse if the fund’s own investors start pulling out their money. These redemptions force more portfolio sales. In our example, the fund’s value is ultimately slashed by more than 60% and its leverage plunges to three times. When leverage is involved, even a modest decline in asset values can provoke a rout.

Table 11.1 Corrosive Power of Leverage

Now consider what happens when there are many such funds, and all receive margin calls and redemptions at the same time. The wave of forced selling drives prices for assets such as mortgage securities sharply lower, further exacerbating investors’ collective problems. This is exactly what happened as 2007 ended. Some funds, backed by larger financial institutions that were worried about their reputations, put up their own cash to meet margin calls. Others stopped accepting redemptions, to try to stem the bleeding. None of it worked. They were overwhelmed by the tidal wave of deleveraging.

No financial institution avoided the fallout from the imploding securities markets. The list of casualties ranged from small boutique investment funds to the giant Swiss banks UBS and Credit Suisse, to Wall Street titans Citigroup and Merrill Lynch. Each day seemed to bring another high-profile blow-up. Financial disaster seemed to lurk in practically every deal. Even making an overnight loan could be a mistake; a borrower could run aground between today and tomorrow.

An often-cited strength of the global financial markets had been their capability to diffuse risk widely; now this strength had become part of the problem. Risk was so widely scattered across the financial system that it was hard to tell who was bearing how much and what the danger of failure really was. Without clarity about which institutions had the bad investments and how much more financial damage was likely, there would be much less borrowing, lending, buying, and selling. As more institutions stumbled, the risk fog grew thicker until liquidity began to evaporate.

Liquidity—the ability to move money in and out of investments or among markets quickly and smoothly—is vital to all financial institutions. Some need it simply to survive. Banks, with their relatively stable deposit bases, weather liquidity storms best. Depositors tend not to move their money quickly (U.K. mortgage lender Northern Rock being a notable exception),8 and even in times of crisis, they tend to stick with banks, particularly those covered by government deposit insurance. This gives such banks a reliable source of liquidity: money the bank can use to make loans or use for other purposes whenever needed.

Other financial institutions also need ready sources of liquidity. Asset-backed conduits and special investment vehicles (SIVs)—institutions that warehoused and invested in mortgage and other securities—obtained theirs by issuing short-term commercial paper. When money market funds and other investors became too worried to buy these IOUs, the conduits and SIVs lost their liquidity and were quickly forced out of business. Broker-dealers such as Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers also relied on being able to raise money quickly. Because they were big, rich, seemingly healthy Wall Street firms, they typically had no trouble getting investors to buy their IOUs. It seemed unimaginable that this confidence would ever be shaken, yet in early 2008, Bear Stearns lost the faith of its creditors. By the middle of March, its funding sources had gone completely dry and the Federal Reserve stepped in to arrange an emergency sale of Bear Stearns to JPMorgan Chase.

Bad Marks

The entire banking system was now under pressure to reduce leverage. When conditions are good and borrowers are making their loan payments faithfully, banks are eager to increase leverage by building up their assets of both loans and securities relative to their capital. Higher leverage leads to big profits, at least in good times. When conditions grow difficult and borrowers fall behind on their debts, banks seek to cut back on leverage to limit losses and protect their capital. This ebb and flow in banking lending defines the credit cycle and gives rise to the old saw that a banker will give you an umbrella when there is plenty of sunshine, but wants it back as soon as it begins to rain.

Amplifying the credit cycle during the subprime financial shock was the use of an accounting standard called “mark-to-market.”9 It’s based on a simple principle: When the market value of an asset changes, the bank or business that owns it must reflect that change on its books. Thus, if a bank makes a loan or buys a security, and after a time that loan or security is worth only 50¢ on the dollar, the bank has to declare that on its balance sheet. Financial regulators adopted mark-to-market rules in response to the S&L crisis and expanded and solidified them after the corporate accounting scandals of the early 2000s when it came to light that Enron and other firms had been manipulating their books to disguise huge losses.

On the face of it, mark-to-market seems like a way to keep the financial system healthy as well as honest. If asset prices decline, those asset owners should have to acknowledge the losses and move on. Had more businesses done that in the 1980s, America might have avoided the S&L debacle and Japan might not have lost a decade of growth during the 1990s, when its banks were paralyzed by all the bad loans they refused to recognize and the economy starved for credit.

But as appealing as the theory behind mark-to-market is, it can present serious problems in practice. Sometimes, such as during the subprime financial shock, marking to market is almost impossible because there are no market prices that make much objective sense. In the midst of the shock, prices for mortgage and other securities bounced around wildly or simply flat-lined as trading in these assets froze. Even the Aaa-rated tranches of mortgage-backed securities, which remained highly unlikely to suffer losses in the long run, were being traded at steep discounts or were not traded at all. Yet under mark-to-market accounting rules, the banks that held these securities had to write down their securities drastically. The distressed prices could have reflected investor fear or a temporary gap in trading and would thus eventually right themselves, but the banks nonetheless had to record the lower prices.

Some institutions tried a different tack: Instead of using mark-to-market, they used “mark-to-model.” In the absence of a functioning market for some highly complex securities, they turned to their own in-house mathematical models to calculate what the securities’ values should be under normal conditions. Of course, these models typically concluded that prices should be higher; nonetheless, this tactic didn’t play well with regulators, and the modelers eventually had to slash the value of their holdings as well. The losses were huge, at least on paper. By early 2009, the globe’s biggest banks had collectively written down their assets by more than $1 trillion (see Table 11.2). The losses were a direct hit to the banks’ capital.

Table 11.2 Total Write-Downs and Credit Losses on U.S. Financial Assets (Write-Downs Since January 2007)

The banks’ problems were aggravated further by the fact that even as losses eroded their capital, their assets were growing rapidly. This wasn’t a conscious choice by the banks, and it made them appear even weaker and more risk prone by increasing their leverage just when they needed to reduce it. Many had agreed earlier to prop up the asset-backed conduits, structured investment vehicles, and broker-dealers in case they needed funds. Now these troubled institutions needed funds desperately, and some drew down long-standing credit lines with the banks. In other cases, bridge loans the banks had made to finance private equity deals just prior to the subprime shock were effectively converted into long-term loans; the troubled junk bond market had made it impossible to refinance or sell off the loans as originally planned. Banks were dragged into becoming the lenders-of-last-resort for much of the financial system. They didn’t view it as an honor.

By mid-2008, the net result was that banks were hemorrhaging capital and were awash in assets they didn’t want. Their leverage was rising at a time when they desperately wanted to reduce it. They had two choices: either raise more capital or shed any assets they could. They did both. With each quarterly round of earnings announcements, bank after bank reported billions in losses and followed this by announcing they had found an investor willing to take an equity stake in the bank. Many of these white-knight investors were sovereign wealth funds, large investment pools set up by foreign governments such as Abu Dhabi, Singapore, China, Korea, and Qatar, filled with the dollars these governments had earned from soaring energy prices and trade with the United States. They were the only investors with the ready cash needed to fill at least some of banks’ capital hole.

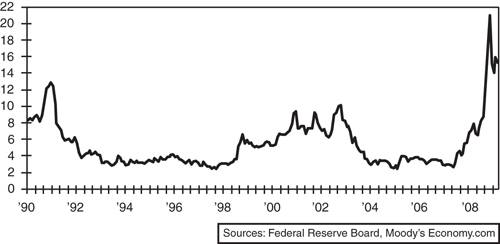

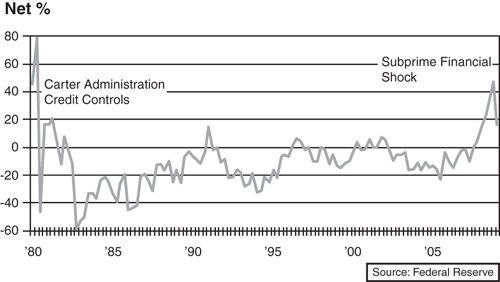

Even the sovereign wealth funds didn’t have enough capital to rescue the banks. By year-end 2008, some of the global financial system’s most venerable institutions, such as Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch, Wachovia, and Washington Mutual, had not survived. And those that remained going concerns were effectively nationalized such as Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and AIG, or were getting capital infusions from U.S. taxpayers. Even this wasn’t enough to lift the intense financial pressure to reduce their leverage and pull back on their lending. They aggressively ratcheted up their standards for all new potential borrowers. New, rigid lending criteria applied not just to subprime or alt-A mortgage loans—those were simply unavailable under any circumstances—but also to prime mortgage borrowers, credit card and student loan borrowers, and businesses of all sizes and stripes. Borrowers who in more normal times would have no problem getting a loan now couldn’t get any bank’s attention. According to a quarterly Federal Reserve survey of senior loan officers at the nation’s major banks, lending standards were tighter than at any time since Jimmy Carter temporarily imposed credit controls on lending in 1980 (see Figure 11.4).10 Marking to market, a much-praised feature of the modern banking system, had instead become part of the problem, reinforcing a vicious and self-reinforcing credit crunch.

Figure 11.4 Credit crunch: net % of banks tightening consumer loan standards.