12. Timid Policymakers Turn Bold

Policymakers’ early response to the subprime financial shock was sometimes halting and, other times, confused. They misjudged the extent of the shock’s economic and financial damage and were hamstrung by its complexity. They also feared bailing out undeserving homeowners, mortgage lenders, and investors; this would be unfair to people working hard to stay current on their mortgages and would embolden more reckless risk-taking in the future. But instead of dousing the turmoil, the tentative policy response fanned it. Investors didn’t expect to be bailed out, but they were distressed by the government’s reluctance to provide help.

As financial and economic fallout spread, policymakers were forced to take stronger and more dramatic steps to combat the crisis. The Federal Reserve and U.S. Treasury gracefully resolved the Bear Stearns collapse in spring 2008, but their takeover of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and the decision to let Lehman Brothers declare bankruptcy in September 2008 set off a chain of events that brought the system to the edge. The economic downturn intensified, becoming the key issue in the 2008 presidential campaign. The new president and Congress had to do much more, and soon did.

By early 2009, the Federal Reserve had slashed interest rates effectively to zero. The Fed had also devised a range of novel mechanisms to help not only the commercial banks it regulated, but also the investment banks and insurance companies it technically did not oversee. Finally, the central bank began effectively printing money. With trillions of newly created dollars, the Fed began to buy everything from corporate commercial paper to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac mortgages, to Treasury bonds. Adopting a strategy most economists had known only from theoretical papers and economic history books, the central bank essentially “monetized” the nation’s debt.

At the same time, the newly installed Obama Administration was pushing a massive fiscal stimulus through Congress. The legislation included hundreds of billions in aid to hard-pressed state and local governments, more help for those losing their jobs, tax cuts for households and businesses, and increased spending on infrastructure—roads and bridges, the electric grid, even the Internet backbone. The new stimulus was nearly five times as large as the one the Bush Administration and Congress had cobbled together a year earlier.

To stem surging foreclosures and their pernicious effect on house prices, the Obama Administration also launched the most aggressive effort to stem foreclosures since the financial shock first hit. The new plan proposed to subsidize mortgage payments for strapped homeowners, aiming to make house payments affordable and thus keep thousands of households from defaulting on their loans.

But the biggest and most difficult problem facing the Obama Administration remained cleaning up the banking system. The nation’s biggest banks were choking on trillions in toxic assets, leaving them dangerously short of capital. The only way to restore normal lending, and thus begin to heal the economy, was to provide banks the capital they needed and rid them of their problem loans and securities. The administration planned to use a combination of taxpayer funds and private investor dollars to get the job done.

Financial markets gave these actions an initial thumbs-up, yet by spring 2009, markets remained anything but normal. Policymakers would need to do still more—another round of fiscal stimulus, a foreclosure plan that reduced the principal amounts homeowners owed, direct purchases of banks’ bad assets—but a comprehensive policy response to the subprime financial shock was finally in place. It would take a few months more to determine how well it was working.

Taking so many major policy steps in such a short period incurred substantial costs. The federal budget deficit was ballooning and soon would dwarf anything experienced since World War II. Although deflation was a real near-term concern, creating trillions of new dollars raised the specter of inflation down the road. It also would not be easy for the government to unwind its sizable ownership stake in the financial system. And unintended consequences would surely flow from some of the policies enacted or even merely considered, such as letting bankruptcy judges reduce mortgages, taxing financial institution bonuses, or bailing out the auto industry. But although these concerns couldn’t be ignored, they also could not lessen the overwhelming necessity for government to tame the crisis. Unless government stepped into the breach left by panicked investors, businesses, and consumers, the economic suffering would be much more severe and, ultimately, much costlier to taxpayers.

Fiddling While Markets Burned

The 2007 subprime financial shock seemed to surprise policymakers. The crisis had begun in earnest in mid-July, but the Federal Reserve didn’t respond until more than a month later. Policymakers cut the federal funds rate target in September and then again in October and December, but the total reduction by year-end amounted to only 1 percentage point. More important for investors, the Fed hinted that each rate cut might be the last, saying inflation was too high to risk accelerating it by lowering rates aggressively. Even with the mid-December 2007 rate cut and financial markets clearly on edge, Fed officials were still hand-wringing about the inflation threat:1

Readings on core inflation have improved modestly this year, but elevated energy and commodity prices, among other factors, may put upward pressure on inflation. In this context, the Committee judges that some inflation risks remain, and it will continue to monitor inflation developments carefully.

The crisis also surprised the Bush Administration. The President maintained consistently that the economy was “fundamentally sound” for months after the shock hit. Treasury Secretary Paulson confidently forecast that the housing market had hit bottom just weeks before markets began to unravel. “I don’t see [subprime mortgage market troubles] imposing a serious problem,” Paulson argued. “I think it’s going to be largely contained.”2

The administration didn’t respond concretely to the crisis until the end of August. Recognizing that foreclosures were mounting, the President proposed legislation to make it easier for troubled homeowners to sell out before they faced foreclosure. This was usually a preferable option, saving both homeowners and their lenders a costly trip through the legal system—but the tax code discouraged it by treating any mortgage debt forgiven by a lender as taxable income. A lender might be willing to let a distressed homeowner sell at a loss, writing off the difference instead of foreclosing, but the homeowner would need to pay taxes on that difference. Distressed homeowners with no cash to pay their tax bill had the Hobson’s choice of going through foreclosure or stiffing the IRS. The Bush bill proposed to fix this by eliminating the tax liability on mortgage debt forgiven in a so-called short sale.

The President also unveiled a new program called Federal Housing Administration (FHA) Secure, designed to help homeowners who were delinquent on their mortgage loans as a result of a payment reset.3 To qualify for the program, homeowners had to have been current on their payments prior to the reset, made at least a 3% down payment, and have sufficient income and a stable job. In announcing the plan, the president declared that “it’s not the government’s job to bail out speculators or those who made the decision to buy a home they knew they could never afford.” Despite being well-intentioned, it quickly became clear that FHA Secure would be of little real help; the hardest-pressed homeowners didn’t have the down payment or the necessary income to qualify. Even under the best of circumstances, the administration expected the program to help only a quarter-million households avoid foreclosure—a trivial number as foreclosure forecasts surged into the millions.

The administration followed up in October with a second program, called Hope Now. This was a consortium of mortgage lenders, services, and investors brought together to find an efficient way to modify mortgage loans. Millions of subprime borrowers were facing large mortgage payment increases at the time; the average reset was expected to be $350 per month, an overwhelming amount for most ordinary working families. The Hope Now agreement established rules to let lenders keep mortgage rates frozen temporarily, enabling these homeowners to keep paying under their original loan terms. The Treasury Department played a vital role, bringing together the diverse range of players who set loan terms, each with its own financial interests and understanding of the process. No one had ever contemplated the need to revise (or “modify”) many millions of mortgage loans at once, and the system didn’t seem up to the task on its own.

Hope Now helped open communications between stretched homeowners and mortgage servicers, but not as much as expected. Instead of substantially modifying many loans, mortgage services put most delinquent homeowners on repayment plans. This provided no relief; the plans simply let delinquent homeowners resume paying their mortgages with no change in terms; they also had to make up any missed payments and pay the associated penalties. Monthly payments actually rose in most of these repayment plans. Hope Now also failed as the nature of the problem changed. As the Fed aggressively lowered interest rates, the pending mortgage resets (which were tied to prevailing short-term interest rates) began to look less dire. Instead, homeowners now were struggling with plunging housing prices and negative mortgage equity. Hope Now’s program did not involve lowering the principal on distressed mortgages; it only tinkered with their interest-rate terms. Now, with millions of homeowners underwater (their home’s market value was less than the loan amounts), defaults rising, and policymakers searching for new ideas to keep people in their homes, financial markets began to writhe.

Policy Paralysis

Policymakers had significantly misjudged both the severity of the shock and its broader economic implications. At most, they assumed this would be a normal, even therapeutic, correction of financial markets that had simply become overvalued. They reasoned that although the housing market had been struggling for more than a year, housing prices had only begun to decline, and stock and bond prices had been rising almost continually since just after the tech-stock bust.

Markets were overextended, but policymakers had no idea how much. Prices had risen sharply in nearly all markets—not just housing, and not just in the United States. Prices for everything from Chinese stocks to European corporate bonds, to U.S. commercial real estate were juiced up. Leverage had helped drive asset prices sky high; investors were borrowing aggressively to finance their trades. And this wasn’t a matter of investors asking their friendly local banker for a loan; instead, investors were issuing short-term IOUs to faceless financial institutions across the globe. The web of financial relationships had grown so complex that it was hard to tell who was taking how much risk and what would happen if bets went bad. When they did go bad, a simple, healthy market correction rapidly turned into a rout, and policymakers were caught unaware.

Policymakers’ confusion was exacerbated by their inability to gather timely and accurate information. Unlike past financial crises, when most of the players involved were regulated and had to report regularly on their risks and financial health, rapidly evolving institutions that had little or no regulatory supervision were driving this crisis. Policymakers knew little to nothing about them. Global regulators had discussed whether and how these new institutions should report on their activities, but they had gotten nowhere. U.S. Treasury officials were particularly uninterested in restricting the financial system; they believed the marketplace could discipline itself. The Bush Administration’s philosophy was to keep government out; financial markets should work out problems on their own. Yet without a regulatory structure in place, policymakers at the U.S. Treasury, the Federal Reserve, and elsewhere had no way to judge the severity of the shock, and they lacked the expertise to respond to it.

Adding to the policy paralysis were the Federal Reserve’s worries about inflation. The Fed’s legal mandate is to keep both inflation and unemployment low, but policymakers appropriately believe that focusing mainly on inflation is the most efficient way to ensure both objectives in the long run. Stable prices let the economy function efficiently, ultimately creating more jobs and holding down unemployment. Yet the broader forces shaping inflation had turned less positive as the benefits of the Internet boom began to fade and productivity growth slowed. Soaring oil and other commodity prices were adding to the inflationary pressures. As the subprime shock loomed in 2007, interest rates were still low by historical standards, and with oil prices hovering over $100 per barrel, Fed officials reasoned that aggressively lowering rates in response to a financial crisis would only fan inflation more broadly. That was the last thing they wanted to do.

Policymakers also worried about something called moral hazard. This is a principle with roots in the insurance industry: It says that people are more likely to take risks if they are insured against the consequences. If your car is 100% covered against theft, you’re less likely to lock your doors. Similar principles govern financial markets: If investors believe the Federal Reserve will cover or lessen their losses, for example, they will take greater investment risks. It is reasonable to argue that when the Fed cut rates aggressively in response to the 1987 stock market crash, the collapse of hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management in 1998, or even the tech stock bust in 2001, it planted the seeds of moral hazard, which led to the latest financial crisis. Therefore, Fed officials feared that lowering rates quickly in response to the subprime shock would only set the stage for bigger financial problems in the future, with complacent investors taking even bigger risks.

Other federal policymakers were less concerned about the moral hazard issue. The Democratic leadership in Congress wanted to do more to respond to the subprime shock, but acting quickly was all but impossible. Congress could pressure banking regulators to toughen their oversight of unscrupulous mortgage lenders, but passing legislation was a different matter. Some in Congress worried that they would overreach, citing Sarbanes–Oxley, the act that changed accounting and corporate governance rules in the wake of the Enron and Arthur Andersen scandals. Mortgage and financial service industry lobbyists also worked hard to slow any legislative action.

Policymakers were also receiving conflicting messages from their constituents. Homeowners who were facing foreclosure pleaded for government help, but others who were struggling but managing to stay current on their mortgages questioned the justice of such government assistance. Why provide relief to people who had gotten in over their heads with a big house purchase, while prudent families in smaller homes got nothing?

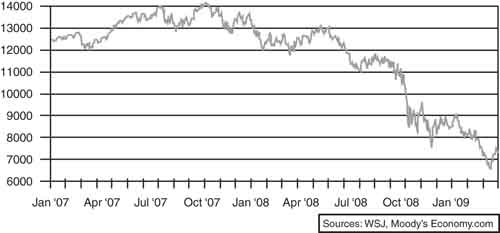

But while the government dithered, the financial turmoil worsened. The longer policymakers delayed acting, the more investor panic spread. The subprime shock had begun in the residential mortgage securities market, but now it was infecting the corporate bond market, the market for commercial mortgage securities, and even the normally low-risk municipal bond market. The stock market, which had held up well in the weeks following the shock—the Dow Jones Industrial Average hit a peak in early October 2007—now stumbled badly. By early 2008, stock prices had fallen almost 20% (see Figure 12.1).

Figure 12.1 Stock investors lose faith: Dow Jones Industrial Average.

Even major global banks became reluctant to lend money to each other, demanding hefty interest rates for loans of any length. It was astonishing, but the world’s largest financial institutions had suddenly become nervous that they wouldn’t get their money back. Banks also worried that they might need the cash if their own investments went bad and their own long-standing lenders cut them off. The cash squeeze became particularly acute as the end of the year approached, normally a season when the demand for cash is greatest. LIBOR, the interest rates banks charge each other for short-term funds, spiked.4

Outside the Monetary Box

At the Federal Reserve, theoretical concerns over inflation and moral hazard were quickly being overwhelmed by practical concerns that a credit crunch was developing. Not only were people with clear credit problems no longer able to get loans, but even borrowers with solid credit histories faced usurious rates and onerous terms. This raised a new set of alarms among policymakers: Tighter credit for weak borrowers would slow the economy, but a crunch that affected creditworthy borrowers as well would likely bring on a recession.

The Fed began trying to ease pressures in money markets by encouraging banks to use its discount window. This part of the Federal Reserve provides a way for some, but not all, financial institutions to borrow cheap money in times of need.5 Although the subprime shock was clearly a time of need, institutions were reluctant to use the discount window. Historically, borrowing from the Fed that way had been a signal that a bank was in precarious financial health, and bankers feared it would scare away customers and other financial institutions, worsening their problems. The Fed tried lowering the rate on discount-window borrowing, permitted borrowing for a longer term, and even cajoled a few too-big-to-fail money center banks to use the discount window, just to show others it was okay. Nothing worked. Banks were hungry for cash, but they didn’t approach the discount window, for fear of being seen as losers whom the market would let starve.

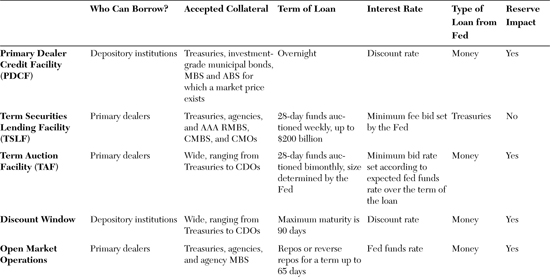

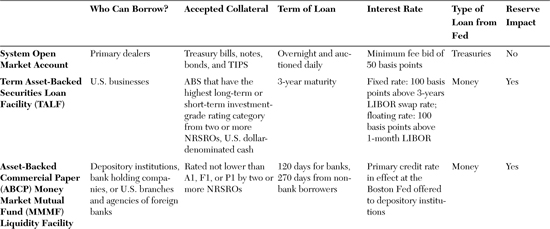

With the banking system increasingly cash-strapped and discount-window borrowing at a standstill, the Fed became creative. In mid-December, the central bank unveiled an alternative to the discount window, which it called the Term Auction Facility (TAF). It enabled institutions to bid for short-term funds by putting up a wide range of securities, including mortgage-related instruments, as collateral (see Table 12.1).6 In a TAF auction, the bids begin at a rate above the federal funds rate but well below the discount rate, thus providing institutions with at least the cover of a reason to borrow funds from the Fed other than potential financial stress. It worked: Because no apparent stigma was attached to borrowing from the TAF, response was strong, beginning with the first auction. Although money markets were still not functioning normally by mid-2008, worries that the banking system might grind to a halt for lack of cash had faded.

Table 12.1 What’s in the Federal Reserve’s Monetary Toolbox?

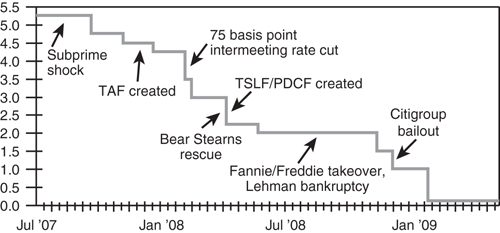

In late January 2008, Fed officials took even more convincing action. In an unscheduled emergency meeting, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) slashed the Fed funds rate target by three-quarters of a percentage point, the biggest such reduction in decades (see Figure 12.2). At their regularly scheduled January meeting a few days later, the committee cut rates again, by an additional half percentage point. For the FOMC, changing interest rates in between its normally scheduled meetings was a clear signal that the financial system was in crisis. And added together, the two rate cuts in January were unprecedented.7

Figure 12.2 The Fed goes on high alert: federal funds rate target.

The Bernanke-led Fed was sharply departing from the Fed’s pattern under former Chairman Greenspan, in which rate changes were typically incremental moves of one-quarter of a percentage point. Greenspan had cut rates by as much as half a point in times of stress, but never more. He had worried that if a larger cut didn’t prove effective, his policy would be questioned, undermining confidence in the Fed. Chairman Bernanke jettisoned this concern; he signaled that he was willing to adjust monetary policy whenever the Fed’s forecasts for inflation and growth changed.

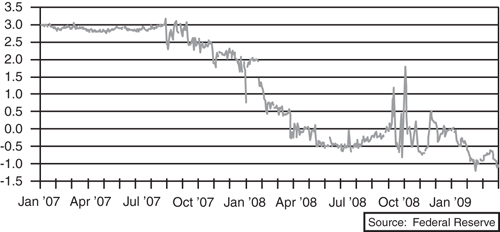

Those forecasts were changing fast in early 2008. In just a few weeks, policymakers went from expecting the economy to slow modestly, to believing it would come close to stalling, to thinking a recession was likely.8 Historically, when the economy has been in recession, the real federal funds rate goes negative—the benchmark interest rate falls below the rate of underlying inflation.9 The real funds rate went negative in spring 2008 as the Fed lowered the nominal rate to 2%, about the same rate as inflation (see Figure 12.3).

Figure 12.3 The Federal Reserve girds for recession: real federal funds rate target.

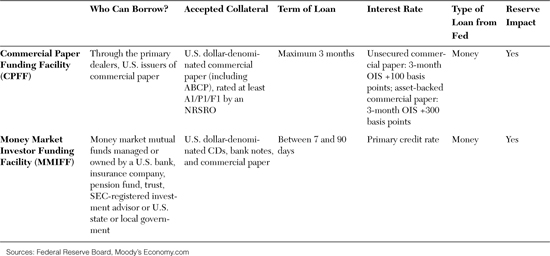

The Federal Reserve was now fully engaged in staunching the bleeding from the subprime shock, but its actions couldn’t keep the crisis from spreading to other parts of the financial system over which the central bank had less influence. Most worrisome were the rumors swirling about potential liquidity problems among Wall Street’s so-called broker dealers. These companies are investment firms that buy and sell securities, both for customers and for themselves (see Table 12.2). They often are highly leveraged, borrowing to make big bets on securities ranging from U.S. Treasury bonds to exotic and risky securities backed by mortgages. When they bet right, their profits can be huge—but when they bet wrong, they can end up as Bear Stearns did in mid-March 2008.

Table 12.2 Who Are the Broker-Dealers?

BNP Paribas Securities Corp. |

Banc of America Securities LLC |

Barclays Capital Inc. |

Cantor Fitzgerald & Co. |

Citigroup Global Markets Inc. |

Countrywide Securities Corporation |

Credit Suisse Securities (USA) LLC |

Daiwa Securities America Inc. |

Deutsche Bank Securities Inc. |

Goldman, Sachs & Co. |

Greenwich Capital Markets, Inc. |

HSBC Securities (USA) Inc. |

JPMorgan Securities Inc. |

Lehman Brothers Inc. |

Merrill Lynch Government Securities Inc. |

Mizuho Securities USA Inc. |

Morgan Stanley & Co. Incorporated |

UBS Securities LLC |

Bear Stearns bet big on the residential mortgage market. It not only issued mortgage securities, but it also had acquired mortgage-lending firms that originated the loans that went into those securities. Bear “made a market” in mortgage securities, meaning it would either buy or sell—whichever a customer wanted. It prospered during the housing bubble, but as the housing and mortgage markets collapsed, each of Bear’s various business segments soured in turn, and confidence in the firm’s viability weakened. Unlike commercial banks that collect funds from depositors, a broker-dealer relies on other financial institutions to lend it the money it invests. If those other institutions lose faith and begin withdrawing their money, the broker-dealer’s only options are filing bankruptcy or, as in Bear Stearns’ case, selling out.

During a tumultuous weekend in March 2008, the Federal Reserve engineered the sale of Bear Stearns to JPMorgan Chase. The Fed acted out of fear of what a bankruptcy could have meant for the financial system, given Bear’s extensive relationships with banks, hedge funds, and other institutions around the world. Policymakers were legitimately worried that the system would freeze up. When it was finished, the Fed had agreed to absorb any losses on $29 billion in risky Bear Stearns securities that JPMorgan acquired in its takeover of the failed firm.

To quell fears that other broker dealers might follow Bear Stearns, policymakers established two new sources of credit for them: the Term Securities Lending Facility (TSLF) and the Primary Dealers Credit Facility (PDCF). The TSLF enabled broker-dealers to borrow Treasury securities from the Fed in exchange for various other securities, including Aaa residential mortgage-backed securities, for up to a month. The PDCF provided overnight loans to broker-dealers at the discount rate and accepted an even wider range of securities as collateral. The TSLF and PDCF provided much-needed liquidity to the broker-dealers and stabilized financial markets, at least temporarily.

Economic Stimulus I

As the struggling economy soared to the top of voters’ lists of concerns in early 2008, it quickly dominated the policy debate in Washington, DC. The sense of political urgency was highlighted in early February, when in just a few days, the Bush Administration and Congress came to terms on a sizable and reasonably well-designed fiscal stimulus package.10 It was an astonishing show of bipartisanship; not only was there broad agreement that this was necessary, but very little debate occurred about what should be in the plan. Policymakers felt it critical to get something done quickly.

The package was worth $168 billion, equal to a little more than 1% of the gross domestic product (GDP). It included tax rebates for lower- and middle-income households, with checks to be mailed between May and July 2008, and tax incentives to spur business investment and put people to work. Economists debated just how large a boost the stimulus would provide—the administration said it would add about half a million jobs—but few believed the medicine would provide more than temporary relief if the housing market and financial system didn’t begin to recover as well.11

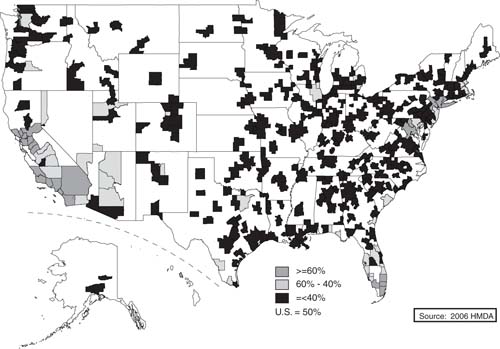

The stimulus package did include some modest housing help; it significantly raised the caps on mortgage lending by the FHA, Fannie Mae, and Freddie Mac.12 The previous caps made it all but impossible for these agencies to provide mortgage credit in areas of the country where high housing prices required large home loans.13 These included places such as California, southern Florida, New York City, and Washington, DC (see Figure 12.4). Because private lenders weren’t making loans, perhaps these federal lenders could fill at least part of the void. This was a striking policy reversal for the Bush Administration; only a few weeks earlier, the White House had emphatically said no to such a move. Until the crisis, administration officials had been intent on reining in these agencies, demanding that Congress pass reforms before expanding their lending powers. That the administration could forget its long-running feud with Fannie and Freddie—both institutions traditionally had much stronger Democratic support—and let them take on such a prominent role in solving the subprime financial shock was proof of how events had unnerved politicians of nearly all stripes.

Figure 12.4 Government lending helps most here: nonconforming share of ’06 mortgage originations.

The administration even went along with relaxing Fannie and Freddie’s capital requirements. This had been a contentious political issue earlier in the decade. A serious accounting scandal occurred at the two lending agencies; their books were so tangled that for years no one knew how much they were earning or losing. OFHEO, the agency that oversaw Fannie and Freddie, had issued penalties in the form of higher capital requirements—in effect, giving them less money to play with.14 But now both institutions were suffering their own credit problems, and losses were making it harder for them to grow. The administration realized that unless it reversed OFHEO’s rule and relaxed the capital requirements, Fannie and Freddie wouldn’t be able to ramp up their lending and help ease the mortgage crisis.

The administration didn’t stop there; it also granted Fannie and Freddie permission to increase their purchases of mortgage loans and securities. OFHEO had put limits on the growth in their holdings—also punishment for their past bad behavior—but with no one else buying, the mortgage securities market was choking. The Federal Home Loan Banks were also permitted by their regulator, the Federal Housing Finance Board, to substantially increase their security holdings.15

The Bush Administration quickly retreated from its long-held positions in an effort to stem the financial crisis and developing recession. Markets weren’t figuring it out by themselves—they needed government help. And the parts of government most valuable in addressing the crisis were the very ones the administration had previously wanted to restrict or dismantle. The administration viewed the FHA, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the Federal Home Loan Banks as, at best, anachronistic and, at worst, risks to the financial system. These institutions were now the centerpiece of the policy response to the subprime finance shock.

Government Misintervention

This strategy turned shaky almost immediately during summer 2008, as the financial health of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac grew more tenuous. The mammoth mortgage lenders had ventured off their traditional low-risk turf, where they specialized in lending to borrowers with good credit scores and ample down payments; now they began investing in riskier alt-A securities. The loss rates on Fannie’s and Freddie’s loans were still low by industry standards, but they were rising and starting to threaten the institutions’ very thin capital cushions. The average commercial bank held $10 worth of assets for every $1 of capital; Fannie and Freddie’s ratio was as high as 70 to 1. The two firms had never been thought to need as much capital as ordinary banks, since they were lending to such good borrowers; now that they were lending to less creditworthy borrowers, their capital appeared inadequate.

The investors who owned Fannie and Freddie stock and debt began to openly worry they might fail. The two firms’ share prices plunged and their borrowing costs rose. All this made it difficult to extend mortgage credit, which policymakers were counting on to help stabilize the sinking housing market; rates on their mortgage loans also began to rise, just the opposite of what policymakers were hoping. Treasury Secretary Paulson aimed to shore up investor confidence when, in July 2008, he reaffirmed and expanded Fannie’s and Freddie’s lines of credit with the Treasury. Investors were only briefly appeased and grew even more convinced that Fannie and Freddie were headed toward insolvency. In early September 2008, the Treasury placed Fannie and Freddie in conservatorship, effectively nationalizing them. Debt-holders were safe, but shareholders were wiped out.16

The financial crisis that had begun a year earlier unraveled into a panic. The seizure of Fannie and Freddie signaled to investors that their stakes in even the largest financial institutions were at risk. The weakest link in the financial system, broker-dealer Lehman Brothers, came under immediate pressure as shareholders sold their stock, and short-sellers took advantage of the downdraft. Lehman had access to cash, thanks to the TSLF and PDCF, but one by one, Lehman’s business partners dropped away, seeing the firm as too risky to do business with. The company was spiraling toward bankruptcy.

The Treasury and the Fed worked feverishly to find a buyer for Lehman but came up short. Treasury officials decided not to intervene, arguing that they couldn’t bail out every financial institution and that Lehman’s counterparties had plenty of time to prepare after the Bear Stearns collapse months earlier. The Fed went along, arguing that it could not, by law, loan Lehman any more without collateral.

The Treasury and the Fed made a grievous mistake; they misjudged the fallout from the Lehman bankruptcy. One of the nation’s oldest money market funds, the Reserve Primary Fund, was choking on its investments in Lehman paper. The Reserve Fund “broke the buck” (the value of its assets fell below what it owed its investors), which, in turn, broke the psyche of small investors, who thought of a money fund as one step removed from a mattress. Redemptions from money funds surged. Money funds are the largest buyers of commercial paper, the short-term IOUs issued by the largest companies, and when the funds stopped buying and started selling commercial paper to pay off scared depositors, the market seized up. Stock investors were terrified; if companies couldn’t issue commercial paper, many couldn’t meet payrolls, finance inventories, or pay vendors. A huge amount of commerce would simply cease.

Other major financial institutions were teetering. Fearing Lehman’s fate, venerable broker-dealer Merrill Lynch hastily sold itself to Bank of America. Shakier banks suffered silent runs as scared depositors with more than the FDIC insured limit of $100,000 moved their funds. Wachovia, a top-five commercial bank, was forced to sell itself to rival Wells Fargo, and WAMU, the nation’s largest Savings & Loan, was folded into JPMorgan Chase. In the midst of this turmoil, insurance colossus AIG told policymakers it, too, was in serious financial trouble. The company had been aggressively writing insurance on mortgage-backed securities via the credit default swap market. As the value of those securities declined and the cost of the insurance it was providing rose, the credit-rating agencies downgraded AIG debt. Other financial institutions that had bought the credit insurance demanded more collateral, which AIG didn’t have. Fearing another Lehman-like event, the Fed extended AIG a multibillion-dollar loan in exchange for a majority ownership stake. The financial system seemed about to shut down.

In late September, a visibly shaken Treasury Secretary Paulson and Fed Chairman Bernanke appeared before Congress with a plan to calm the mounting turmoil. They called it the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP). Paulson and Bernanke wanted Congress to devote $700 billion to rescuing the financial system. For such a huge sum, the plan was shockingly short on details. Why $700 billion? This was roughly equal to the system’s likely losses. What would the money be used for? No restrictions would govern how the money could be deployed, but Paulson’s plan was to buy “toxic” assets from distressed banks. Who would oversee how the money was spent? That would be worked out at some point in the future. Would any restrictions be placed on institutions that benefited from the TARP money? That, too, would be determined at a later date, but policymakers argued that restricting executive compensation at firms receiving help would be a mistake because it could dissuade them from participating.

TARP brought about a groundswell of protest among taxpayers, who simply couldn’t understand why they should pay for Wall Street’s mistakes. Banks had made the bad loans; they should fix them. Asking taxpayers for $700 billion to clean up the mess was beyond the pale. Congress was flooded with calls opposing the plan.

Despite the uproar, the Democratic leadership in the House thought it had just enough votes to squeak TARP through and called a vote. Although many in Congress didn’t fully understand the gravity of Secretary Paulson and Chairman Bernanke’s warnings, the election six weeks away made taxpayers sound loud and clear. Congress voted down the TARP. The consequences were evident immediately: The stock market cratered. The House reversed its vote a week later, but in the furor, Paulson’s plan for using the TARP money changed. Instead of buying toxic assets, the Treasury decided to buy equity directly in the nation’s largest banks. To sell this idea, however, policymakers had to convince the public that these banks were too large to fail. Meanwhile, to further shore up confidence, the FDIC insurance limit was increased to $250,000, insurance was provided to money funds, and the government guaranteed bank-issued debt.

A tenuous calm prevailed in financial markets through the presidential election. Money fund redemptions slowed, bank runs ended, and no other major failures occurred. Even the stock market held its own after its September downdraft. That lasted until mid-November, when Secretary Paulson said he no longer planned to use TARP money to buy toxic assets. Market prices for residential and commercial mortgage securities tanked on the news. Banks that owned these assets—notably including once-mighty Citigroup—came under immediate intense pressure. The Treasury and Fed once again were forced to step in to stop a bank failure, this time by guaranteeing hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of Citigroup holdings.

The Bush Administration had taken office early in the decade holding the belief that financial markets would effectively police themselves; if they got into trouble, it was on them to get themselves out. Government intervention would only create moral hazard, encourage imprudent risk-taking, and lead to worse problems in the future. By the time Bush left office, however, his administration had jettisoned its scruples about moral hazard and was intervening aggressively. Washington had mis-stepped badly, letting a severe yet manageable financial crisis become an uncontrollable panic. The financial system was a shambles and the economy was in its worst downturn since the Great Depression.

Printing Money

The Fed was already thinking well outside its monetary policy box, working overtime to invent new tools for combating the crisis. policymakers had dropped their main benchmark interest rate, the so-called federal funds rate, effectively to zero and said publicly it would stay there indefinitely. Even more dramatic, the Fed was ramping up a policy called “quantitative easing,” essentially creating money by fiat to buy financial assets. The central bank had already been buying commercial paper and securities issued or guaranteed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Policymakers also signaled that they could soon be buying long-term Treasury bonds and thus monetizing the nation’s debt.

In addition to stepping up security purchases, the Fed expanded its lending via a parade of new lending facilities, essentially offers to provide cash under specific terms to different groups of financial institutions. The first, called the Term Auction Facility (TAF), began in late 2007 to get short-term cash to banks. The newest, as of spring 2009, was called the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF) short. This aimed to give private investors the wherewithal to buy newly issued Aaa securities backed by residential and commercial mortgages; credit card debt; and student, auto and small business loans. The Fed was also willing to guarantee troubled assets to backstop struggling financial institutions, a tactic used successfully with Bear Stearns, AIG, and Citigroup.

The Fed took unprecedented steps to deal with an unprecedented financial and economic crisis. Yet despite more than a year of aggressive government policy, credit markets remained frozen and the banking system was still in disarray. Except for Treasury yields, which had never been lower, interest rates that consumers and businesses face remained disconcertingly high. Given the collapse in bond issuance and the tightened lending standards, many borrowers couldn’t obtain credit at any price.

The recession was intensifying, due to the credit crunch, crumbling confidence, and the loss of wealth. The Real GDP was falling sharply, with no sign of stabilization in housing, consumer spending, or business investment. Deflation was a mounting threat as businesses were forced to cut prices to make sales. Core consumer price inflation came to a standstill in early 2009 and looked set to go negative. Businesses had little choice but to cut jobs and investment, which only exacerbated the decline in sales and threatened to push the economy into a pernicious, self-reinforcing deflationary cycle.

Quantitative easing would ultimately succeed in short-circuiting the deflationary cycle and reviving the economy. This was already evident in the commercial paper market. After the Fed began buying commercial paper directly from issuers, rates fell and issuance picked up. The Fed’s program was so successful that it grew measurably smaller over the first quarter of 2009.

The decline in long-term Treasury yields and fixed mortgage rates also showed how much power the Fed still had. After the Fed said it would buy long-term government bonds, 10-year Treasury yields plunged to near 3%. Fixed mortgage rates fell to just above 5%, pulled down by both lower Treasury yields and narrowing mortgage spreads after the Fed bought debt and mortgage securities from Fannie and Freddie. If spreads kept falling toward their long-run averages, fixed-rate mortgages seemed likely to approach 4.5%. That seemed enough to ignite a new refinancing boom—most existing mortgage loans carried rates around 5.5%—and to support stronger home sales when the downdraft in the job market abated.

Just how far the Fed would need to take quantitative easing and its lending facilities would depend on how quickly the financial system responded. It was not hard to imagine the Fed ultimately extending its reach to all asset markets, from mortgage-backed securities to municipal bonds and corporate debt.

All this added to concerns that the Fed wouldn’t be able to gracefully unwind its massive intrusion into the financial system. Many worried that the Fed’s strategy would ignite runaway inflation after the crisis abated. After all, inflation is a monetary phenomenon, and the Fed was printing dollars by the trillions.

Although inflation could well grow uncomfortably high at some point, it was not likely to validate such fears and was certainly not a reason for the Fed to hold back in its response to the crisis. Money ignites inflation only if it first leads to more and less costly credit, fueling tight labor markets and sending utilization rates up against capacity constraints. Policymakers would have time to respond before this transpired; in the wake of the crisis, it might be years before credit flowed freely again and the economy found its way back to full employment.

Also important was that most of the Fed’s liquidity was in the form of very short-term loans—less than 90 days. When the financial system and economy found their footing, policymakers could without much difficulty allow these programs to simply fade away.

The Fed was expected to begin normalizing interest rates by summer 2010. By that time, the financial crisis will have subsided, and house prices and the broader economy will be stabilizing. policymakers will be reluctant to keep rates too long too low, a mistake that the Fed seemingly made coming out the tech-stock bust early in the decade. This contributed to the housing bubble at the root of the epic financial crisis.

Economic Stimulus II

The new Obama Administration also swung immediately into crisis management. Just a few weeks after Obama took office, the administration and Congress came to terms on a massive fiscal stimulus plan. It included tax cuts and increased government spending totaling nearly $800 billion, to be mostly distributed through the end of the decade. This equaled 3% of the GDP in 2009 and 2010, the largest stimulus since the New Deal of the 1930s.

Of the $800 billion, some $300 billion was in tax cuts to individuals and businesses, $250 billion in aid to fiscally strapped state and local governments, $150 billion in various kinds of infrastructure spending, and $100 billion in additional income support to workers who were losing their jobs.

Income support and aid to state and local governments was intended to provide quick help to the economy. Without this relief, workers who were losing their jobs had little choice but to immediately slash spending, costing the economy even more jobs. In most cases, state and local governments struggling with falling tax revenues must balance their budgets by cutting payrolls and programs and also raising taxes, adding to the economy’s burdens. Federal help for the unemployed and for state and local governments was thus intended to prevent even worse job losses.

Tax cuts stimulate job creation as individuals spend and businesses invest some of their new cash. But the near-term economic benefits of individual tax cuts are diluted because some is saved and some is used to repay debt. These aren’t bad things in themselves, but they don’t help the economy as much as spending the money quickly. The stimulus plan also helped the troubled housing and auto industries with tax breaks, including a nonrefundable tax credit worth up to $8,000 for first-time home buyers who made a quick home purchase, and a write-off of state sales taxes and interest on loans to buy new vehicles.

The economic benefits of infrastructure spending are generally not quick—it takes time to get these projects underway—but they are significant, particularly for the depressed construction and manufacturing industries. The economy was expected to struggle well into the next decade, so this spending was expected to be particularly welcome in 2010 as the impact of the other stimulus efforts faded. The stimulus plan drew criticism for its mixed bag of infrastructure targets, from roads and bridges to the electric grid and the Internet backbone. But given the uncertain returns on such projects, diversification is probably a plus. Moreover, the Japanese experience during their “lost decade” of the 1990s showed there are diminishing returns to infrastructure spending. Investing only in bridges, for example, ultimately produces bridges to nowhere.

Concerns arose that the stimulus plan’s price tag was too large. It would be paid for with borrowed money, adding significantly to the government’s already swelling debt load. But without a stimulus, the economy would sink further as consumers and businesses retrenched, undermining tax revenues and fueling more government spending, producing even larger deficits and debt burdens. Fortunately, the United States is still the global economy’s triple-A credit; even though the subprime financial shock began in the United States, global investors still preferred the safety of U.S. Treasury bonds. The United States was thus still able to borrow at record-low interest rates.

Indeed, a more significant criticism of the stimulus plan was that it was too small. The struggling economy was set to produce nearly $1 trillion less than it was capable of during 2009 and will almost surely fall short again by as much in 2010. The $800 billion in spending and tax cuts to be distributed during this period will not fill this expected hole in the economy. Nonetheless, the hope was that, when combined with the other aggressive policy steps being taken, the stimulus plan would go a long way toward curtailing the downdraft in the economy.

Foreclosure Mitigation

With the economic stimulus plan in place, the Obama Administration turned its focus on foreclosure mitigation. Foreclosures undermine house prices because foreclosed property is dumped on the housing market at deep discounts. They also choke the banking system, as losses on defaulted mortgages mount. There had been a string of policy efforts to stem foreclosures by facilitating mortgage refinancings and loan modification, dating back to late 2007 with FHA Secure and Hope Now, but these efforts had been overwhelmed. So within just a few weeks of taking office, the administration put forth a comprehensive plan to shore up the housing market and stem the foreclosure crisis.

Broadly, the administration’s housing policy aimed to support single-family housing demand by lowering the cost and increasing the availability of mortgage credit. At the same time, the initiative worked to control housing supply by offering refinancing and mortgage loan modifications as alternatives to foreclosure.

More specifically, the plan made mortgage credit cheaper and more widely available by empowering Fannie and Freddie. Because these institutions were now part of the federal government, they had no shareholders to appease and making profits was no longer a priority—making more and cheaper mortgage credit was. One way Fannie and Freddie were asked to do this was to refinance loans that they owned or insured but had been precluded from refinancing because the homeowner didn’t have the requisite 20% down payment because of falling house prices.

A major mortgage refinancing boom looked imminent in spring 2009. With the Federal Reserve aggressively buying Fannie and Freddie debt and mortgage securities, conforming mortgage rates were drifting below 5%. About $3 trillion in Fannie and Freddie loans (more than one-fourth of all mortgage loans outstanding) carry mortgage rates higher than 5% and would be good candidates for refinancing if rates fell much lower. This would do less to prevent foreclosures—subprime, alt-A, and jumbo borrowers are having the most trouble making payments—but it would reduce mortgage payments and save borrowers tens of billions of dollars, adding more stimulus to the economy.

The administration’s housing policy also included a large mortgage-modification plan targeted primarily at owner-occupied homes with troubled subprime and alt-A loans. The plan involved using tens of billions in taxpayer dollars to provide lucrative incentives to homeowners, mortgage servicers, and mortgage owners to engage in substantial loan modifications. There were lower mortgage payments and subsidies for homeowners who stay current on modified loans, payments to servicers who successfully modify loans, and, in some circumstances, payments to mortgage owners who agree to the modifications.

Ultimately, the number of loans modified will be up to mortgage owners. Owners of subprime and alt-A mortgage loans are mainly global financial institutions that invested in mortgage securities backed by the loans. These owners benefit only if a modification significantly reduces the chance of default. Thus, their calculation is sensitive to the borrowers’ probability of default before and after the modification. The probability of default, in turn, depends on the equity position of the homeowner. A deeply underwater homeowner will still be liable to default, even with a lower monthly payment. Add one financial setback—say, a leaky roof—and default may be a rational choice. Indeed, loan modifications to lower monthly payments have not worked out particularly well thus far. The OCC said more than half the loans modified in this way in early 2008 had defaulted again six months later. The bottom line is that, given the complexity of the calculation for mortgage owners, ultimately there may be fewer modifications than the administration hopes for, and it could take longer for modifications to get going in earnest. Still, the plan will substantially increase loan modifications and reduce foreclosures.

The administration’s housing initiative also included legislation to change bankruptcy law, allowing homeowners in a Chapter 13 filing to have the principal on their first mortgage reduced—crammed down—to the home’s current market value. Under current law, bankruptcy judges may reduce most consumer debts, but not a first mortgage. The logic is that by not allowing first-mortgage cram-downs in bankruptcy, mortgage rates remain lower and credit stays more available.

Policymakers likely hoped the proposed change would not increase bankruptcy filings, but rather encourage mortgage owners to modify more loans. Bankruptcy judges have significant latitude to rearrange households’ finances and could impose greater losses on mortgage owners than they would face by participating in the modification plan. The bankruptcy law would be the stick persuading mortgage owners to take the financial carrots in the modification plan.

Even so, a change in the law could lead to substantially more Chapter 13 filings. Some homeowners would find this alternative more attractive than a loan modification, particularly those significantly underwater or with high total debt loads. Indeed, bankruptcy could put some homeowners on firmer financial ground and thus lower the chance of future default more than modification would.

Some concerns about such bankruptcy legislation are misplaced. The change would not significantly raise the cost of mortgage credit because the change would apply only to loans already originated. The likelihood that abuses by distressed homeowners would increase is also low, given that a workout in Chapter 13 is financially painful. Indeed, the number of bankruptcy filings has remained surprisingly low since the late-2005 bankruptcy reform, reflecting the much higher costs to households filing for Chapter 13.

Yet it is reasonable to worry that rising bankruptcies would hit other consumer lenders hard. Unsecured credit card lenders, in particular, could lose substantially as judges significantly reduce or eliminate credit card debts. If a million more households filed for bankruptcy because of cram-down legislation and the average household had $50,000 in credit card debt, the potential loss to credit card lenders would be $50 billion. Complicating matters further, most credit card debt has been securitized; these securitizations could fall apart if the losses are great enough.

Changing bankruptcy law to allow for first-mortgage cram-downs would forestall more foreclosures and thus help alleviate the housing crisis. But there will be costs, some known and some still unknown.

The administration’s housing policy came under fire from various critics, with the most vitriolic arguing that it rewarded bad behavior by homeowners and mortgage owners, that bankruptcy reform abrogates contracts, and that the plan will hurt the financial system. Others argued that the plan’s cost to taxpayers, estimated at $275 billion, was too high.

These criticisms have some merit, but without such a plan, everyone’s cost will be higher—in soaring foreclosures, lower house prices and household wealth, a measurably weaker financial system and economy, and even greater costs to taxpayers. In certain respects, the administration’s housing policy was not aggressive enough, and an even larger policy response might ultimately be needed.

Financial Stability

Solving the nation’s banking crisis was the Obama Administration’s most intractable problem. There hadn’t been a major financial failure since late 2008, but many banks didn’t have enough capital and were reluctant to make loans to consumers and businesses. Until the banks’ capital hole was filled, the credit crunch would strangle the economy.

New Treasury Secretary Geithner had presented the rough outlines of what he called a financial stability plan in February, but this did more harm than good because the outline was so rough that it suggested to financial markets that there was no real plan. The stock market hit a new low in early March, some 50% below its peak in late 2007. Household nest eggs had literally been cut in half.

The stakes were thus extraordinarily high when the Treasury unveiled substantially more details on the plan in mid-March. It would combine as much as $100 billion from the Troubled Asset Relief Program with private investment and debt financing guaranteed by the FDIC, and have the capacity to buy up to approximately $1 trillion in toxic assets. The plan also involved expanding the Fed’s Troubled Asset-Backed Securities Lending Facility program to purchase legacy (previously issued) securities on banks’ balance sheets. TALF had originally been designed only for newly issued securities.

Toxic assets are loans, or securities backed by loans, on which the borrowers are behind or in default. The assets are thus worth a lot less than when the loans were originally made. The resulting loss cuts into the banks’ capital, the financial cushions they need to remain in business. Making the problem worse is that banks don’t know how toxic these assets will ultimately prove to be: Will a delinquent borrower eventually default? Given that uncertainty, banks are unsure how much capital they will need (particularly because raising new capital from investors is nearly impossible at this time) and, therefore, are nervous about making new loans. The key idea in the Treasury’s plan was to have the federal government finance the purchase of these toxic assets and create certainty for the banks so they could resume lending normally.

One attractive feature of the plan was that it relied on only a handful of private investors; their job would be to bid for toxic assets that willing banks put up for auction, to determine a fair price. The government would then finance purchases of these assets on a large scale at these prices. Private investors should be attracted to the auctions, given the potentially high return on their money, the limited downside (because the federal government is also participating), and efforts to ensure that they would not face compensation and other management restrictions, unlike institutions receiving TARP money. The logic was that there was a difference between receiving taxpayer dollars directly, via the TARP, and partnering with taxpayers, as was being proposed.

This was important, given the furor over retention bonuses paid to AIG traders, the very same people who had driven the insurer into the ground and cost taxpayers a couple hundred billion dollars. Contracts between AIG and some of its traders had been signed before the government had stepped in. And although the government now owned nearly 80% of the company because it had not gone into bankruptcy, those contracts were still enforceable. It was absurd, but the Treasury felt that it had no legal recourse but to allow the bonuses to be paid. Congress was infuriated and considered legislation to tax the bonuses away. The Treasury’s financial stability plan would work only if private investors participated, and they wouldn’t participate if they thought Congress might at some point impose retroactive taxes or other penalties. Policymakers had to assuage those concerns.

Another attractive feature of the Treasury’s plan was that the FDIC played a key role, conducting the auctions and guaranteeing the debt financing for the purchases of toxic assets. The FDIC sells assets all the time as part of its resolution of failed banks. Using the FDIC for debt financing also did not require the Treasury to go back to Congress for approval, which could have been problematic in the current political environment. Private investors will manage the assets after buying them in the auctions.

Purchasing $1 trillion in toxic assets wouldn’t be enough to solve the banking system’s problems; the program probably needed to be at least twice as large. The volume of toxic assets on U.S. bank balance sheets that had not already been written down was between $2 trillion and $2.5 trillion. To cover losses on these assets, the government would ultimately need an additional $300 billion to $400 billion (on top of the $700 billion already spent on TARP). The up to $100 billion they planned to commit on this plan was a good start, but officials would eventually have to ask Congress for more. If things worked well enough, however, Congress would likely provide more money to solve the banking problem once and for all.

There were reasons to worry that the plan would not work as well as hoped. Banks could be reluctant to offer assets for sale in the auctions, believing they still wouldn’t obtain a good price. Private investors could stay away, rather than risk incurring the wrath of Congress if they made too much money down the road. Weak banks could be pushed under if they were forced to mark the value of their own assets to the prices determined in the auctions, thus putting pressure on taxpayers to come up with more assistance. Given these uncertainties, it would be quicker and more efficient for the federal government to buy the toxic assets directly. But given the various political constraints on this approach—most significantly, the worry that the government would overpay for the toxic assets if it bought them directly—the Treasury’s financial stability plan was a good second-best option.

Indeed, Wall Street liked the plan. Finally some optimism seemed to emerge regarding the prospects for the financial system and the economy. As banks unload their toxic assets and taxpayers provide more capital, the system should slowly begin to pump more credit through the economy. Combined with Washington’s fiscal stimulus (which would take effect in spring 2009), a potentially massive refinancing boom during the summer (as mortgage rates fall firmly below 5%), and fewer foreclosures (as the administration’s mortgage-modification plan kicks in during late 2009), chances were rising that the economy would stabilize by early 2010.

Adding Up the Costs

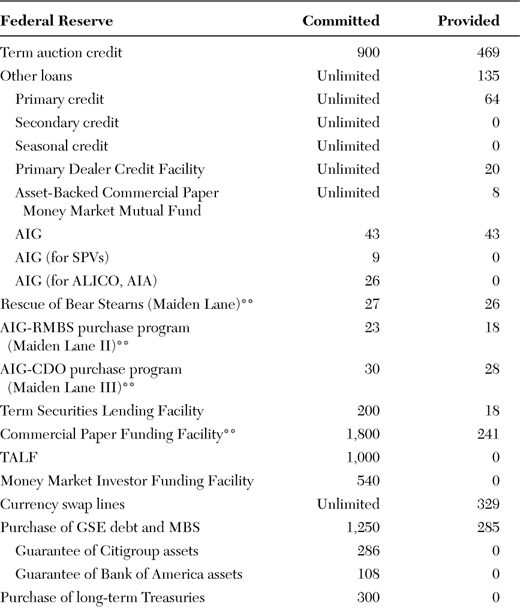

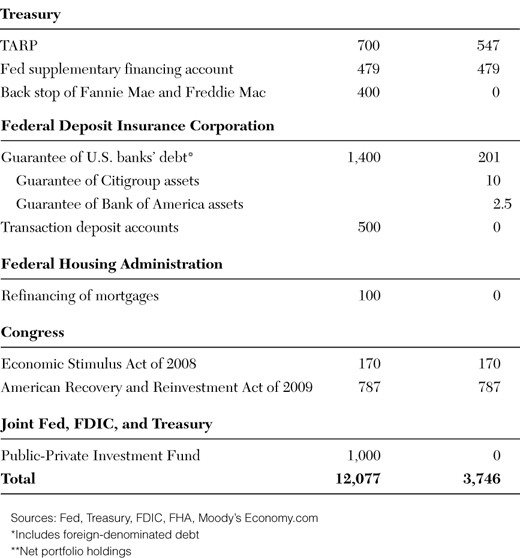

The government’s unprecedented intervention throughout the financial system and economy was necessary to quell the financial panic and stabilize the economy, but the costs to taxpayers were enormous. By March 2009, the commitments policymakers had made to combat the crisis totaled an astounding $12 trillion, of which nearly $4 trillion had already been used (see Table 12.3).

Table 12.3 Government Response to Financial Crisis: $ Billions, through March 2009

This isn’t the final bill for taxpayers—it will be less. Taxpayers will ultimately recoup some of the trillions they lay out as the government sells the assets it accumulates and presumably privatizes its large ownership stake in the financial system. The final price tag isn’t small, however: It could easily approach $3 trillion, equal to more than 20% of the current GDP. For context, the United States savings and loan crisis during the early 1990s cost taxpayers some 7% of GDP, and the Japanese banking crisis that weighed on that economy throughout the 1990s cost Japanese taxpayers at least 10% of the GDP.

Two-thirds of the $3 trillion in expected taxpayer costs is the direct cost of the government response to the financial crisis. This includes nearly $1 trillion in total economic stimulus and another $1 trillion in net costs of what the government has committed to support various financial institutions and markets via such things as $700 billion for TARP, $400 billion for recapitalizing Fannie and Freddie, and more than $2 trillion in Federal Reserve loans and loan guarantees. The remaining one-third of the costs reflects the economic downturn and resulting loss of tax revenues and increased government spending.

The federal government’s fiscal situation, which was already weakening before the crisis, will be extraordinarily worrisome in the wake of it. The nation’s federal-debt-to-GDP ratio, a good measure of the nation’s fiscal health, will increase from close to 45% of GDP (about the average over the period since World War II) to more than 65%. And unless big changes in tax and spending policy come soon, this ratio will move steadily higher even after the financial crisis abates. In just a few years, the outsized baby boom generation will retire en masse and require more healthcare. The costs of Social Security, Medicaid, and Medicare will balloon. This will be untenable. Policymakers must credibly address these long-term budget concerns soon or risk losing the confidence of global investors—the same investors who are buying the trillions in Treasury bonds currently being issued to finance the government’s response to the crisis.

Many other costs from the government’s interventions are difficult to determine. A taste of this is evident from the difficulties created by the government’s big ownership stakes in the nation’s largest financial institutions. Determining appropriate compensation packages for senior management might look easy in comparison to some of the decisions policymakers might yet have to make regarding the operations of these firms. Selling off these stakes somewhere down the road won’t be easy, either. Consider that privatizing Fannie and Freddie could mean somewhat higher mortgage rates and less ample mortgage credit; will future policymakers have the political will necessary to take this step? The list of potential repercussions goes on and on.

The government response to the subprime financial shock had gone from timid to bold. In summer 2007, the Federal Reserve had been uncomfortable lowering interest rates and the Bush Administration had thought giving the FHA the authority to refinance a few hundred thousand troubled mortgage loans would be enough to quell the crisis. By spring 2009, policymakers were engaged in the largest government intervention in the financial system and the economy since the New Deal. The failure to act decisively early in the crisis and a series of policy errors in the middle of it ultimately led to the need for unprecedented government action. The costs of all this are daunting, but the costs of governmental inaction would be measurably greater.