4. Money for Sale

Nature abhors a vacuum. Taking advantage of the financialization of business and everyday life, banks moved to fill the gap.

In the film Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, an economics teacher, played by Ben Stein, launches into an improvised soliloquy, asking his apathetic students whether anyone has seen the “Laffer Curve.” He asks if anyone knows what Vice-President Bush Senior called this in 1980. No one knows. “Something-d-o-o economics. ‘Voodoo’ economics.”

The 1930s Hollywood film White Zombie incorrectly associated voodoo, African beliefs syncretized with Christianity, with exotic superstitions and occult practices. Unscrupulous practitioners made a fortune out of fake potions, powders, fetishes, and talismans to ward off evil. In the 1980s, U.S. President Ronald Reagan embraced voodoo economics. At about the same time, banks created voodoo banking.

It’s a Wonderful Bank!

Every Christmas, Frank Capra’s film It’s A Wonderful Life is repeated. For some, it probably isn’t Christmas until they have seen it again. James Stewart plays every banker George Bailey, who owns and runs the town’s bank. It’s a Wonderful Life portrays a world where the bank acts as an intermediary between savers and borrowers, and bankers are respected members of the community.

Until recently, banks were simple. Regulators set the rates that the bank could pay its depositors, the rates it could charge borrowers, and the amount it could lend. There was little trading. Exotics remained exotic. The world worked to the 3-6-3 rule—borrow at 3 percent, lend at 6 percent, hit the golf course at 3.00 p.m.

Following the 1929 stock market crash and the collapse of the banking system, the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 (named after Democratic Senator Carter Glass of Lynchburg, Virginia, and Democratic Congressman Henry B. Steagall of Alabama) separated commercial banking (taking deposits and lending money) and investment banking (advising, arranging, underwriting, and trading securities). Regulation sought to prevent conflicts of interest where the same institution was lending (granting credit) and investing (using credit). It recognized that institutions accepting deposits wielded financial power through control of other people’s money. Proponents of regulation argued that this power should be limited, to ensure soundness and competition for loans or investments.

In the United States, government insurance of deposits meant that the taxpayer could be required to pay out if an insured bank suffered trading losses. Trading in securities exposed firms to losses that could threaten depositors. Some argued that banks conditioned to limit risk were not equipped to undertake more speculative activities.

In the 1980s, the controls over banks and banking were gradually loosened. President Reagan and UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher favored less government involvement in the economy. In parts of the world like France, deregulation of the financial system was accompanied by privatization of government-owned banks.

Proponents of deregulation argued that distinctions between loans, deposits, and securities were increasingly difficult in practice. In 1977, Merrill Lynch, a securities firm with a large brokerage network known as the thundering herd, launched the cash management account (CMA)—a mutual fund investing in short-term securities offering investors daily access to money, checking facilities, and the convenience of having their pay deposited directly. It was, in reality, a checking or operating account that paid attractive rates of interest. At the time, banks were not allowed to pay interest on checking accounts, placing them at a competitive disadvantage.

Banks argued that perceived conflicts of interest could be managed by enforcing separation of activities—firewalls or Chinese walls. The ability to expand into broader financial services would reduce risk through diversification of activity. Proponents pointed to Europe, where universal banks undertook both banking and securities businesses.

In 1999, the coup de grâce was administered by Phil Gramm (Republican of Texas) and Jim Leach (Republican of Iowa), who introduced legislation repealing the Glass-Steagall Act. The repeal paved the way for financial supermarkets—one-stop money shops taking deposits, making loans, providing advice, underwriting and trading securities, managing investments, and providing insurance. Byron Dorgan, one of only eight senators who voted against the abolition, presciently observed that “this bill will in my judgement raise the likelihood of future massive taxpayer bailouts.”1

Giant financial supermarkets destroyed old banking traditions. Walter Bagehot, the nineteenth-century British economist, saw banking as the preserve of titled families: “The banker’s calling is hereditary; the credit of the bank descends from father to son; this inherited wealth brings inherited refinement.”2 The chairman of Hambros Bank, a leading London merchant bank, was more specific: “Our job is to breed wisely.”3 Inherited refinement gave way to a more industrial form of banking. In David Gaffney’s novel Never Never, a bank manager describes the new regime:

“You’re not selling enough,” [the regional manager] says. “You should be moving more product. Loans, insurance, second mortgages, personal pensions. I say ... that’s not what banking is about in this area. It’s about helping people. They haven’t got the money to be buying things.”4

Banking became a commercial activity driven by shareholder returns. With increasing competition, banks resorted to voodoo to meet investor expectations.

Pass the Parcel

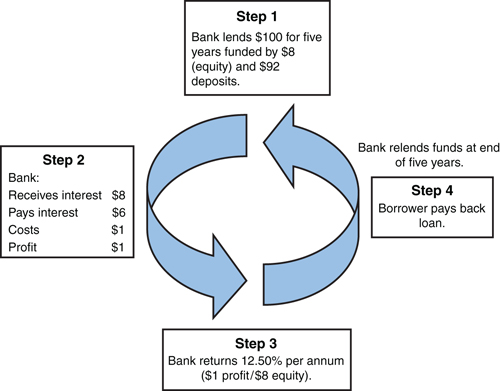

Banks took short-term deposits, using the money to make longer-term loans. The major risk was that the borrower did not pay you back. It was a simple, unexciting business. The bank’s capability to grow depended on its own shareholders’ capital and its capability to garner deposits. The shareholders received predictable, modest returns. Figure 4.1 sets out the traditional banking model.

Figure 4.1. Traditional banking model

1. The bank raises $92 in deposits from clients, combining it with $8 of its own shareholders’ capital.

2. This money ($100) is lent to a client, say for 5 years.

3. The bank receives $8 in interest. It pays $6 in interest to its depositors. The bank has operating costs of $1. The profits before tax of $1 ($8 minus $6 minus $1) translate into a return for bank shareholders of 12.50 percent per annum ($1 in profits, divided by $8 of shareholders’ capital).

4. When the loan is paid back, the whole process repeats.

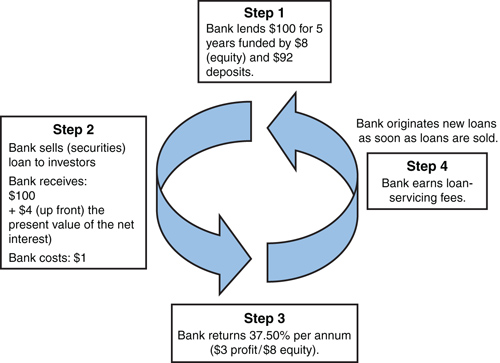

In the new originate-to-distribute model, banks underwrote the loan, warehousing it on the balance sheet for a short time using its own money, before parceling the loans into securities to be sold to investors, in a process known as securitization. Figure 4.2 sets out the originate-to-distribute banking model.

Figure 4.2. Originate-to-distribute model

1. The bank still raises $92 in deposits from clients, combining it with $8 of its own shareholders’ funds to lend $100 to a client for 5 years.

2. Instead of holding the loan for its entire life (5 years), the bank holds the loans until it has a sufficient number and amount to package them up and sell them to investors, such as pension funds, insurance companies, and investment managers.

3. When the loan is sold, the bank receives the amount loaned ($100) plus the current or present value of the net interest (the difference between what the borrower pays and what the investor purchasing the repackaged loans receives). This amount is $4. After operating costs of $1, the bank has profits before tax of $3 ($4 minus $1), translating into shareholder returns of 37.50 percent per annum ($3 in profits divided by $8 of shareholders’ capital).

4. The bank continues to administer the loan during its life, receiving loan servicing fees. After the loans have been sold, the bank’s capital and funding are freed up, and it can repeat the process again.

In the originate-to-distribute model, banks tied up capital for a short time (until the loans were sold off). The same capital could be reused as the process is repeated. Interest earnings over the life of the loan are discounted back and recognized immediately. Banks increase the velocity of capital, effectively sweating the same capital harder to increase returns. If a bank turned over its entire loan book twice a year, its returns would be 75 percent per annum!

Other financial products, primarily derivative contracts, essentially forms of price insurance, were used in the same way. The CEO of one bank noted that they had become “a moving company and not a storage company.”

Loan Frenzy

By increasing throughput, making more loans and selling them off to eager investors, banks created a money machine. Banks traditionally earn the net interest rate margin (the difference between what the borrower pays and what it must pay to depositors) over the life of the loan—annuity income. When loan assets are sold off, the earnings from the loan are recognized up-front. Over the remaining life of the loan, the bank earns modest fees for administering it. Each year, banks now needed to make more and more loans to meet the expectation machine’s demand for higher earnings.

Access to cheap deposits to fund loans traditionally gave commercial banks an advantage over investment banks and nonbank lenders. The originate-to-distribute model allowed investment banks, mortgage brokers, and independent credit card providers to make loans and sell them off. They could now obtain cheap funding from investors. The competition led to lower profit margins, forcing everyone to increase loan volumes to meet investor demand for higher returns. Everybody had to run harder just to stay where they were.

The race was to find borrowers. Banks outsourced the origination of the loans to brokers, incentivized by large upfront fees. Everybody first lent to the soundest borrowers. Then, less creditworthy borrowers (previously denied access to credit) entered the market. Then came even more risky loans—subprime mortgages for NINJA borrowers and loans to private equity funds and hedge funds.

Traditional lending practices relied on character. After his bank avoided losses on property loans in the early 1970s, Lord Poole of Lazards set out his successful lending criteria: “I only lent money to people who had been at Eton [an elite English school with a distinguished alumni].”5 Who qualified for loans, on what terms and at what rate, now relied on credit scores—a numerical expression of the risk based on statistical analysis of financial information. The models relied on purely historical factors that sometimes did not reflect changes in the world. Information fed into the models was not checked.

Loans relied on the value of collateral securing the debt. Borrowers put up a portion of the price of the asset, agreeing to cover any fall in value with additional cash. Little attention was paid to the accuracy and stability of the value of the collateral. The ability to repay the loan diminished in importance. As the value of the collateral was expected to increase, it was assumed that you would refinance your loan to pay back the previous borrowing.

Bankers argued that loans to low-quality borrowers were not risky, as the banks did not plan to hold on to them. Banks were only at risk in the period before the loans were sold. All this underpinned an unprecedented growth in lending.

Plastic Fantastic Money

The average American has around five credit cards. In 2005, there were 6.1 billion credit card offers to Americans.

In 1992, Emily Grant received a letter from American Express: “We don’t invite most people to apply for the American Express Card. We are inviting you.” Emily Grant happened to be the daughter of James Grant, founder of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer. In a caustic piece,6 Grant pointed out that his daughter was 11 years old, received an allowance of $2.50 each week and could probably pay the $55 annual fee but that would leave little remaining funds in her savings account. Shortly afterward, Grant’s 10-year-old son Philip received his own offer to apply for the even more prestigious gold Amex card: “Charges are approved based on your ability to pay, as demonstrated by your spending and payment patterns, and by your personal resources.” Grant wrote that Philip’s resources were an allowance of $1.50 each week, and his savings were negligible, following heavy investments in raffle tickets for a school fair.

The modern credit card grew out of merchant credit schemes to purchase fuel or items from department stores. Ralph Schneider and Frank McNamara created Diners Club, which pioneered the concept of customers paying different merchants using the same card, eliminating the need for multiple cards. In 1958, American Express commenced operations, ultimately creating a worldwide credit card network. Visa evolved out of the BankAmericard created in 1958 by Bank of America. Other banks created MasterCard, which eventually incorporated Citibank’s proprietary Everything Card. Copying the concept, Barclays Bank launched Barclaycard in the UK in 1966.

In the mid-1980s, John Reed, then head of consumer banking at Citibank, expanded the acceptance and use of credit cards with an audacious campaign. Citi mailed credit cards with a small limit to householders based on their postal codes, filtering out undesirable neighborhoods. The scheme helped the rapid adoption of credit cards, but Citibank at first experienced high bad debts because many card holders could not or did not pay the bank back for things they bought. Over time, the business became very profitable for the bank.

The idea of the credit card—a simple revolving loan for individuals—has remained constant. Financial institutions issue credit cards to approved customers, allowing them to use it to make purchases up to a specified limit at businesses that accept the card. When a purchase is completed, the card issuer pays the business. Each month, the cardholder may repay the entire amount owed by a specified date. Alternatively, the cardholder must make a minimum payment, usually a defined minimum proportion of the bill. If the cardholder does not pay the bill in full (known as revolvers), the card issuer charges a high rate of interest on the unpaid balance.

Card issuers make money from the cardholder—annual fees and interest on balances owed. Card issuers also make money from businesses that accept the card—a merchant discount of 1–5 percent of each purchase and a flat per-transaction charge.

In the 1990s, credit cards based on the value of the card holder’s home emerged. Rising home prices and repayments of their mortgages meant that many homeowners were rich on paper—the value of the house was greater than the amount owed on their mortgage. A credit card secured against this value allowed individuals to unlock their home equity.

Credit card marketing is slick—“Life Flows Better with Visa”; “Live richly, Citibank”; “Priceless! For everything else there’s MasterCard.” Cards are linked to the good life and the consumption that goes with it. Each dollar spent may generate bonus points toward a prize or air miles. Cards related to an entity like a university, return a percentage of the spending on the card to the affinity group. In developing countries, a credit card is frequently a sought after symbol of Western modernity, signifying sophistication and progress. Consumers agreed with Marshall McLuhan, the Canadian media theorist: “Money is a poor man’s credit card.” Nobody wanted to be poor.

Credit cards are now even objets d’art. Specialists in numismatics (the study of money) and exonumia (the study of money-like objects) collect old paper merchant cards, metal tokens once used as merchant credit cards and early credit cards made of celluloid plastic, fiber, and paper.

In October 2008, MasterCard launched its diamond credit card, inlaid with a 0.02-carat gem and laced with gold. The card featured an image of a peacock for female cardholders and a winged horse for men. It targeted new super-rich billionaires created by the oil and minerals boom of recent years in commodity-rich Kazakhstan. Kazkommertsbank, the second largest bank in Kazakhstan, planned to issue 1,000 cards, at a rate of about 30 a month, to VIP customers. Each card had an annual fee of $1,000 and a credit limit of $50,000, more than twice the limit on MasterCard platinum cards.

The instant gratification provided by readily accessible money replaced restraint and deferred consumption. In the new economy, there were three kinds of people: the haves, the have-nots, and the have-not-paid-for-what-they-haves.7

Casino Banking

Banks also began to trade financial instruments, taking the advice of Fear of Flying author Erica Jong: “If you don’t risk anything then you risk even more.”

Initially, banks traded currencies and government bonds. Volatility of currencies increased following the collapse of the Bretton Woods agreement and the demise of the gold standard. Volatility of interest rates increased, following removal of controls on interest rates and a rise in inflation as a result of the oil shocks of 1974 and 1979. Derivatives—different forms of price insurance on currencies, interest rates, and equities—began trading in the 1970s.

As volatility forced businesses and investors to hedge their financial risks, banks moved into the protection racket. Initially, they acted primarily as an intermediary, matching transactions between clients. Over time, banks began to take positions without having a matching counterparty. Competition meant margins kept getting lower. Competitors shamelessly copied new products, reducing profits. Banks maintained earnings through higher volumes, innovation, and increased risk taking.

Increasing volumes meant finding new customers to trade with. Hedge funds, that traded frequently and aggressively, became important clients. Banks created prime brokerage units to settle and clear trades, lend to, and raise capital for hedge funds. With growing wealth and sophistication, investors moved out of bank deposits into equity, bonds, or mutual funds. Banks created or purchased wealth management businesses (fund managers and private banks) to meet the demand for investment products. Wealth management clients became major purchasers of securities or financial products created by the banks. Major banks expanded geographically, especially into emerging markets, where similar products could be created and sold to new clients.

In trading, banks rely on their counterparts to perform contractual obligations, sometimes over many years. Needing to overcome the risk of dealing with less creditworthy clients, banks created a system known as collateral—clients lodged an initial deposit (an agreed percentage of the contract value), agreeing to top up this amount as necessary to minimize risk. Banks now could trade with anybody and did.

Complexity grew rapidly, with banks creating exotic products, usually derivatives, to trade with clients. Increased computing power and quants, highly trained staff with mathematical or quantitative skills, accelerated this process. Banks managed the risks and calculated their earnings using complex models.

If one bank offered an option with a somersault, then a second offered the same with a somersault and pike, while a third marketed one with a triple somersault and pike ending in a double tuck. In a surreal sequence, banks created instruments using models that few understood, which they traded with clients who did not understand what the product was and had no way of pricing or valuing it. The level of knowledge of clients was often inversely proportional to the complexity of the product.

Banks increasingly speculated on price changes to supplement shrinking margins from client transactions. Traders used information gained from trading with clients to make money. Banks all wanted to become flow monsters—institutions that traded with everybody, capturing a large share of total trading volume.

Banks now invested their own money in transactions, becoming principals in deals. Where they lent money to an investor to purchase a business, the banks co-invested alongside the client. Clients liked banks investing in transactions they financed or advised upon to ensure better alignment of their interests. Advisory work in mergers and acquisition and corporate finance became conditional on extension of credit at skimpy margins. Banks seeded or invested in hedge funds to gain preferential access to business. Investing their own funds allowed banks to make ends meet. But traders were now betting the house’s money.

Classically trained bankers quoted Herodotus: “Great deeds are usually wrought at great risk.” Traders stayed with Lillian Carter, mother of President Jimmy Carter: “I don’t think about risk much. I just do what I want to do. If you gotta go, you gotta go.” It was a long way from George Bailey’s wonderful world. Banks should all have heeded Mark Twain’s acid wit: “There are two times in a man’s life when he should not speculate: when he can’t afford it, and when he can.”

Confidence Tricks

Originally created to help facilitate German war reparations after the First World War, the Bank of International Settlement (BIS) established the basic framework under which banks operated, from its HQ in Basel, Switzerland. The first set of global bank regulations, known as Basel 1, emerged in the early 1980s.

Banking involves risks. Borrowers may not pay back loans—credit risk or default risk. Banks may lose money trading if prices move against them—market risk. Depositors may want their money back—liquidity risk. Liquidity risk arises because banks take deposits typically for short periods (less than 12 months) to make loans for longer terms (up to 30 years)—known as maturity transformation. Basel 1 required banks to maintain capital, a buffer or reserves (shareholders’ money), against loss. They were required to hold cash or securities that could be readily sold to raise funds to meet the needs of depositors wanting to take out their money.

The eighteenth-century English playwright Susannah Centlivre observed that: “Tis my opinion every man cheats in his own way, and he is only honest who is not discovered.” Regulatory arbitrage—the process of exploiting gaps in bank regulations—evolved into a business model.

Banks reduced the amount of expensive capital, transferring loans, investments, and trading into a network of unregulated off-balance-sheet vehicles, which did not need to hold as much capital as the bank itself. Frequently, the real risk remained with the banks. Banks reduced real capital—common shares—by substituting creative hybrid capital instruments that were cheaper. High income was used to attract fund managers and “mom and pop” (ordinary) investors, while disguising the (less obvious) risks. Banks used these new forms of capital to finance repurchase of their shares to boost returns. CitiGroup repurchased $12.8 billion of its shares in 2005 and an additional $7 billion in 2006, just before its share price plunged as the bank suffered huge losses.

Banks decreased their equity and cash reserves, assuming they could always buy these resources from the market at a price in case of need—this came to be known as purchased capital and purchased liquidity. Banks had reduced the amount of capital and spare cash at the same time as they were increasing loan volumes, taking on more risk and increasing leverage. The bank’s return on capital, the measure investors looked at, increased as the denominator (capital) fell and simultaneously the numerator (return) rose. Like David Hockney, the English artist, bankers knew that: “The moment you cheat for the sake of beauty you are an artist.”

The financial system became more fragile and dangerous as banks became larger. As Baltasar Gracian, the Spanish philosopher and writer, noted in the seventeenth century: “One deceit needs many others, and so the whole house is built in the air and must soon come to the ground.”

The Citi of Money

On April 6, 1998 Citicorp and Travelers merged to create CitiGroup in a $83 billion deal that was another “deal of the century.” Sandy Weill, chief executive of Travelers, and John Reed, chief executive of Citicorp, announced the merger at New York’s Waldorf Astoria Hotel. The men wore matching ties dotted with red umbrellas—the original logo of Traveler.

The merger combined Travelers’ insurance, brokerage, and securities businesses and Citicorp’s international banking operations. It was to be the ultimate universal bank or financial supermarket, with hundreds of millions of customers in more than a hundred countries.

The Travelers/Citicorp juggernaut would use its huge balance sheet to make large loans to companies and leverage this to sell the clients a variety of other advisory services or financial products. The institution’s unparalleled reach would offer a one-stop-shop for individuals—payments, credit cards, mortgages, savings, and investment products. But as the baseball player Yogi Berra noted: “In theory there is no difference between theory and practice but in practice there is.”

Synergies and cross-selling benefits failed to emerge. Competition limited CitiGroup’s gains. Other commercial banks built or bought investment banks to compete. i-Banks, the new buzzword for investment banks, shamelessly derivative of Apple’s ‘i’ products—particularly Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, and Merrill Lynch (collectively dubbed MGM)—changed their business models to match the universal banks.

At an internal conference in the early 1990s, John Thornton, a Goldman Sachs managing director, outlined a business model. Eschewing the traditional PowerPoint presentation, Thornton used a felt pen to draw dots on a white board. “These are the important people in the world.” Thornton then drew overlapping circles around the dots. “Inside these circles are the people they know, the deals they do, the ideas they are thinking about. Pretty much everything that happens in the world, happens in these circles.” Pointing to where most of the circles overlapped, Thornton summed up investment banking: “This is where I want to be. That is our strategy.”8

Thornton’s vision was old school—advise clients and underwrite debt and equity issues. Instead, investment banks now transformed themselves into commercial banks. They began lending to clients, in part to protect their advisory franchises from the likes of Citi that were keen to use their lending power to muscle in. Investment banks raised capital to compete with their commercial and universal banking peers. Even mighty “Gold Man Sex,” as foreign clients called the firm, abandoned its hallowed partnership structure to raise the capital needed to support a burgeoning balance sheet and support trading operations.

Citi was born with a golden foot in its mouth. In the 1980s, ill-fated forays into lending to Latin America led to multibillion dollar losses. Citi Chairman Wriston had earlier inaccurately believed: “Countries don’t go bust.” In the early 1990s, Citi nearly collapsed because of poor real estate lending. In the aftermath of the bust of the Internet bubble, Citi’s star telecommunications analyst Jack Grubman was accused of spruiking WorldCom stock in return for investment banking business. Grubman described his role in the following terms: “What used to be a conflict is now a synergy.”9

In 2004, Citi was criticized and then fined for disrupting European markets in the Dr. Evil trade, rapidly selling €11-billion-worth of bonds via an electronic platform, driving down the price, and then buying it back at cheaper prices. In 2007, Citi was fined by the National Association of Security Dealers for violations relating to mutual fund sales practices. In June 2009, Japanese authorities prosecuted Citi for breaches of regulations, following on earlier problems in 2004. The most global thing about Citi was its unending list of problems with regulators in different jurisdictions.

In the end, Citi too came to rely on voodoo banking to boost its lackluster performance. It rapidly increased its lending and risk taking heeding humorist Will Rogers’ advice: “You’ve got to go out on a limb sometimes because that’s where the fruit is.” In the global financial crisis, CitiGroup would suffer near-fatal losses, necessitating majority government ownership.

Sign of the Times

As John Manyard Keynes observed: “A sound banker, alas, is not one who foresees danger and avoids it, but one who, when he is ruined, is ruined in a conventional way along with his fellows, so that no one can really blame him.”10 Celebrated commercial and investment banks from the United States, UK, Germany, Switzerland, and France followed similar strategies.

Profits were driven by rapid and large growth in lending, trading revenues, and increased risk taking. High returns were underwritten by an extremely favorable economic environment, not, as bankers argued, innovation. As John Kenneth Galbraith, in A Short History of Financial Euphoria, identified:

Financial operations do not lend themselves to innovation. What is recurrently so described and celebrated is, without exception, a small variation on an established design.... The world of finance hails the invention of the wheel over and over again, often in a slightly more unstable version.11

The Economist summarized the era:

Over the past 35 years it has seemed as if everyone in finance has wanted to be someone else. Hedge funds and private equity wanted to be as cool as a dot.com. Goldman Sachs wanted to be as smart as a hedge fund. The other investment banks wanted to be as profitable as Goldman Sachs. America’s retail banks wanted to be as cutting-edge as investment banks. And European banks wanted to be as aggressive as American banks.12

They would all end up wishing they could be back precisely where they started.

Elite athletes sometimes use drugs to boost performance. Voodoo banking enabled banks to enhance short-term performance while risking longer-term damage. The problem was they put everybody, not just themselves, in harm’s way. In 2008, discovering the casino banking practices of financial institutions, regulators reacted like Captain Renault (played by Claude Rains) in Casablanca. They confessed that they were truly shocked to find that gambling was going on in regulated banks.