17. War Games

The age of capital was the conscious creation of policymakers and regulators. Central banks even played war games to test their ability to deal with a financial crisis.

In 2002 the U.S. military staged the Millennium Challenge, the largest war game, costing over $250 million and featuring an attack on an unknown oil-rich Middle East country. The good guys, the Blue Force, defeated the bad guys, the Red Force, vindicating Donald Rumsfeld’s new high-tech warfare.

But the Red Force, under iconoclastic retired Marine General Paul Van Riper, actually won the battle, using unconventional strategies. Riper used small boats and planes to sink the Blue Fleet, which if it had really occurred would have been the worst naval defeat since Pearl Harbor. Riper’s Red Force communicated via motorbikes and the muezzin’s calls to prayer, avoiding the Blue Force’s electronic surveillance and destruction of Van Riper’s command and communication infrastructure. The Red Force changed its position and tactics repeatedly, combating the superior strength of the Blue Force.

When it became clear that the Blue Force would not prevail, the script was rewritten for the right result. For Riper, the games were a “mistruth”: “There’s very little intellectual activity.... What happens is a number of people are put into a room, given some sort of a slogan and told to write to the slogan. That’s not the way to generate new ideas.”1 Like the Millennium Challenge, modern economies were built upon incorrect theories and flawed belief systems in a triumph of expediency over inconvenient truths.

In their war games, central bankers looked at bank failures and even the effects of a flu pandemic, but failed to grasp the flimsy foundations of the entire financial system. As Jeremy Grantham, chairman of investment manager GMO, remarked: “I want to emphasize how little I understand all of the intricate workings of the global financial system. I hope that someone else gets it, because I don’t.”2

Borrowed Times

The brave new economy was built on debt. Individuals borrowed to buy houses, cars, gadgets, or take holidays. They borrowed to get an education, to get healthcare. They even borrowed to save, using debt-financed investments. Companies borrowed to invest and to buy each other. They borrowed to pay dividends or repurchase their own stock.

Governments in Australia and the UK swore off debt. But at the first sign of trouble, they fell off the wagon, borrowing furiously. America borrowed in good times because it could and borrowed in bad times because it needed to. Vice-President Dick Cheney stated: “Reagan proved deficits don’t matter.”3

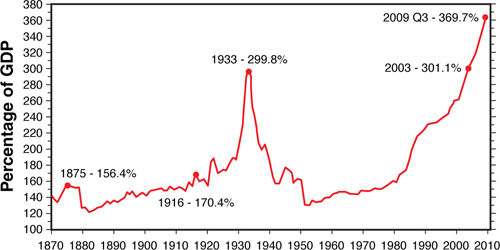

Borrowing levels, especially household, and government, increased rapidly. Figure 17.1 sets out the rapid build-up in debt in the United States. Others—British, Canadians, Australian and New Zealanders—also started to live on borrowed time. Even in the traditionally abstemious eurozone countries, household debt rose from 49 percent of GDP at the end of 1999 to 63 percent by mid-2009. The growth in European debt was driven mainly by the “Club Med” countries (Spain, Portugal, Italy, Greece) as well as Ireland. But other economies also ran up debt, mainly government debt, to finance social spending and entitlements. Savings of thrifty Germans and Asians were recycled to the borrowers and back again as payments for goods they sold.

Figure 17.1. U.S. debt levels as a percentage of GDP

Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Federal Reserve, Census Bureau.

In Hamlet, Polonius counseled: “Neither a borrower nor a lender be; for loan oft loses both itself and friend, and borrowing dulls the edge of husbandry.” It was advice for a different time.

Saving is consumption deferred. Borrowing accelerates consumption, providing instant gratification. All debt borrows from tomorrow to pay for today. To be sustainable, future income must be sufficient to pay the interest and repay the loan. But much of the borrowing in the new economy was now unproductive, financing consumption or larger houses that did not produce income. Earnings from investments were frequently insufficient to meet interest and principal payments.

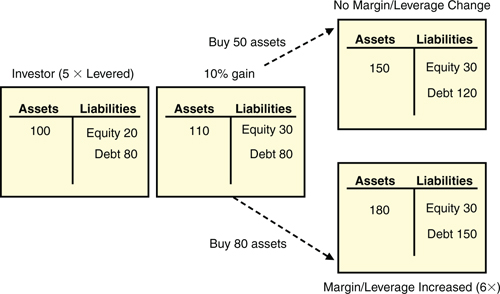

Debt was inextricably linked to the value of assets, especially houses purchased with borrowed money. Figure 17.2 shows the relationship between the supply of debt and the price of assets.

Figure 17.2. Asset purchases using borrowings

Assume an investor uses $20 of its own money—equity—and borrows $80 (80 percent of the value) to purchase an asset for $100. If the asset increases in value by 10 percent to $110, then the investor’s equity increases on paper to $30 ($110 minus the fixed amount of debt of $80). If the investor maintains its leverage at 5 times then it can buy $150 of assets (funded by $30 of equity and $120 of debt). If the investor can now leverage 6 times then it can buy $180 of assets (funded by $30 of equity and $150 of debt). The investor still only has its original $20 investment in cash, unless it sells the asset to realize its paper gains, which can vanish. But now, this $20 supports even more debt, as much as $160 (the $180 of assets that the investor can buy if it leverages 6 times less its original investment). The real leverage is around 9 times, which means an 11 percent fall in the value of the asset purchased can wipe out the investor’s wealth entirely.

Where the supply of assets does not increase as quickly as the supply of debt, the price increases allow the process to continue. Many borrowers could not pay the interest on their debt, needing prices to rise to allow them to borrow more to repay the original loan. The gains are fictitious until converted to cash by selling the asset and paying off the debt. Where prices are rising, no one wants to give up future gains, leaving everyone vulnerable to prices falling.

In America and the UK, increasing paper wealth encouraged reduced savings. The future relied on a spiral of guaranteed rising prices.

Alan Greenspan theorized that “a rising, debt-to-income ratio for households or of total non-financial debt to GDP” did not signify stress but was “a reflection of dispersion of a growing financial imbalance of economic entities that in turn reflects the irreversible up-drift in division of labor and specialization.”4 In 2005, Ben Bernanke, Greenspan’s successor as chairman of the US Federal Reserve, provided an apology for high levels of debt: “Concerns about debt should be allayed by the fact that household assets (particularly housing wealth) have risen even more quickly than household liabilities.”5 In the Great Moderation, debt-driven speculation drove prosperity.

For Bernanke, it was not even a debt problem but a savings problem. He blamed the Germans, Japanese and Chinese for saving too much.6 America was being “neighborly,” helping out. After the global crisis, in a case of severe cognitive dissonance, Bernanke continued to blame the foreign savers for the problems.7

In 1933, the economist Irving Fisher identified the danger: “over-investment and over-speculation are often important; but they would have far less serious results were they not conducted with borrowed money.”8 In 2005, William White, chief economist at the Bank of International Settlement, broke ranks by warning that easy money was creating a boom that would end painfully, reflecting “the size of the real imbalances that, preceded it.” He warned “mistakes...take a long time to work off.”9

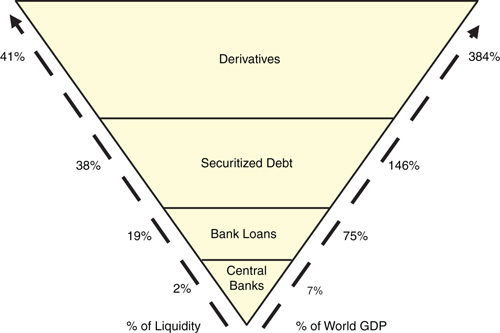

Liquidity Factory

Cotton Candy (candyfloss or fairy floss) is spun sugar, consisting mostly of air. Financial engineering spun real money, expanding it into ever-larger servings—candyfloss money.10 Figure 17.3 sets out the modern money pyramid.

Figure 17.3. The new liquidity factory

Source: David Roche, Independent Strategy (www.instrategy.com). Reproduced with permission.

Until the mid-1980s the money that existed in the world consisted primarily of funds created by central banks (notes, reserves and money held by financial institutions with the central bank) and bank loans. By 2006, this traditional money made up only 21 percent of the total liquidity available. Central banks and bank loans consisted of 2 percent and 19 percent of available money respectively. In dollar terms, central bank money was equivalent to around $4 trillion (7 percent of global GDP of around $56 trillion). Bank loans were around $42 trillion (75 percent of global GDP).

The new liquidity factory or market-based credit11 was based on financial alchemy. Securitization and derivatives now provided most of the money, around 79 percent of total liquidity. Around 38 percent of global money was in the form of securitization, around $82 trillion (146 percent of global GDP). Around 41 percent was in the form of derivative contracts, around $215 trillion (384 percent of global GDP).12 The astonishing growth in global liquidity was driven by financialization.

Banks moved assets off-balance sheet into the opaque, unregulated shadow banking system. The shadow banks depended on short-term debt from professional money markets to fund long-term, illiquid assets. Borrowing against the value of the assets, they were vulnerable to falls in their price. Banks increased the volume of lending and risk, confident in their ability to transfer them to the shadow banks.

Fund manager Pimco’s Paul McCulley identified the trend:

The bottom line is simple; shadow banks use funding instruments that are not just as good as old-fashioned [government]-protected deposits. But it was a great gig so long as the public bought the notion that such funding instruments were “just as good” as bank deposits—more leverage, less regulation and more asset freedom were a path to (much) higher returns on equity in shadow banks than conventional banks.13

The liquidity factory increased debt to levels without historical parallel. The tsunami of debt fuelled price increases in equity, property, infrastructure, and commodities.

Cotton candy eventually collapses into a sticky mess that is a fraction of its original size. In the financial crisis, the entire money pile would collapse in a similar way, entangling the global economy.

Six Degrees of Separation

John Guare’s Six Degrees of Separation popularized the idea that everyone is no more than six steps away from any other person on Earth. Guare’s play borrows from Hungarian Frigyes Karinthy’s story Chains or Chain Link: “using no more than five individuals, one of whom is a personal acquaintance, [you] could contact the selected individual using nothing except the network of personal acquaintances.”14 Financial institutions were now similarly linked through complex networks.

Securitization and derivatives were supposed to deliver a safer financial system. Donald Kohn, vice-chairman of the Federal Reserve, argued that originate and distribute would “enable risk and return to be divided and priced to better meet the needs of borrowers and lenders...permit previously illiquid obligations to be securitized and traded.” Derivatives would convert risk into another commodity to be traded, making “obsolete previous divisions among types of financial intermediaries and across geographical regions in which they operate.” The new business model made “banks and other financial institutions ‘more robust’ and [make] the financial system ‘more resilient and flexible’ and better able to absorb shocks without increasing the effects of such shocks on the real economy.”15

Originate and hide was a more accurate description. Complex chains of transactions allowed risk and debt to move from a place where it was observable to places where it was hidden and unregulated. Trading linked market participants in networks of relationships and interdependence. Bear Stearns was linked to 5,000 parties via 750,000 contracts. Lehman Brothers had more than a 1 million contracts with a notional value of $40 trillion, including more than $5 trillion in credit default swaps alone.

Having insured banks against risk, if AIG was unable to perform under the contracts then the banks lost twice—on the risk hedged and on its hedge for which it had paid. If one bank had financial problems then banks that dealt with it were exposed to losses. If required to post collateral, AIG needed to raise money or sell assets. If AIG sold assets, then as prices fell other holders suffered losses, forcing them to sell their holdings or post additional collateral. It was the epidemiology of sexually transmitted diseases—it wasn’t who you had sex with, but whom those people had slept with, and so on.

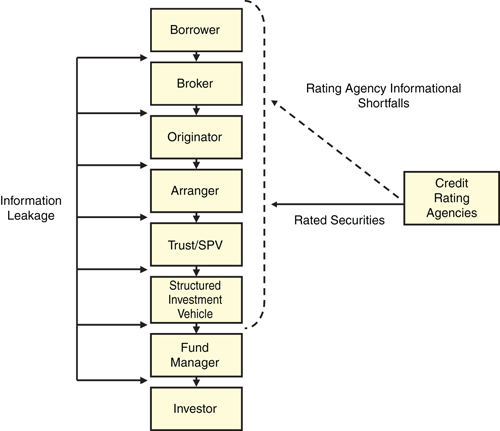

At each stage in the chains of risk, information was lost. Figure 17.4 sets out the information lost in the process of securitizing mortgages. Everybody now relied on someone else to do their risk analysis. William Heyman, former head of market regulation at the US SEC, observed: “In manufacturing, the market price is set by the smartest guy with the best, cheapest production process. In securities markets, the price is set by the dumbest guy with the most money to lose.”16

Figure 17.4. Information asymmetries in securitization

Source: Adapted from BIS Committee on the Global Financial System.

Paper Chains

These risk chains relied on voluminous documents, which only lawyers read but without necessarily understanding what was going on. As became apparent later, the legal basis for some transactions was also flawed. The key to mortgages is the note, the actual IOU where the borrower agrees to pay back the loan. Only the note holder has legal standing to ask a court to foreclose and evict delinquent borrowers from their homes.

When loans are repackaged into securities, the title to the loan must be transferred to one or more SPVs, where the loan is sliced and diced. Once securitized, the loan is entirely virtual as the different MBS tranche holders do not own the loan but have complex claims against payments made by the borrower.

The MERS (Mortgage Electronic Registration System) was created to hold the digitized notes from the actual mortgage loans. Somewhere, the chain of title was broken; the transfer of ownership and the note was not done correctly. The holder of the loan or MBS could not prove ownership. The person who took out the mortgage no longer knew whom to pay. The lender could not foreclose and sell the property to recover the money lent.

As more and more mortgages became delinquent and foreclosures increased, lawyers acting on behalf of home-owners and courts looked into the chain of title, finding the botched paperwork. Foreclosure mills, law firms specializing in foreclosures, allegedly faked and falsified documentation to repair the chain of title on delinquent mortgages. In one firm, a woman deceased in 1995 miraculously continued to sign foreclosure documents until 2008—a phenomenon that came to be known as robo signing. On her website (www.nakedcapitalism.com), blogger Yves Smith even put up a price list from companies specializing in these types of services.

The U.S. government launched investigations and banks were forced to stop foreclosures. Unless remedied, the faulty documentation would mean that delinquent mortgagors would not have to pay back their loans, increasing the losses to lenders and holders of repackaged mortgage loans.

CDO2 transactions re-securitizing MBSs could involve 93,750,000 mortgages and 1,125,000,300 pages of documentation. The Bank of England’s Andrew Haldane recommended that investors deal with the complexity “with a Ph.D. in mathematics under one arm and a Diploma in speed-reading under the other.” He concluded that the task would “have tried the patience of even the most diligent investor.” This meant that “with no time to read the small-print, the instruments were instead devoured whole” and “food poisoning and a lengthy loss of appetite have been the predictable consequences.”17

Toxic Pathologies

Financial systems now comprised a small number of financial hubs with multiple linkages. Between 1985 and 2005 a Bank of England’s analysis of financial networks showed that the linkages had become markedly more dense, complex and concentrated between countries and institutions within countries.18 The system was very vulnerable to disturbances. Problems were transmitted rapidly through the tightly linked system.

The linkages were exacerbated because major players had near-identical business models and risk management practices. Everybody wanted to be Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan or Deutsche Bank, concentrating on the latest fashionable products, equity derivatives, structured credit or prime brokerage. In 1994 Charles Bowsher, comptroller general of the USA, identified the risk: “The sudden failure or abrupt withdrawal from trading of any of these large US dealers could cause liquidity problems in the markets and could also pose risks to others and the financial system as a whole.” Anticipating the events of 2008, he warned that this could require “a financial bailout paid for or guaranteed by taxpayers.”19

In a 2005 paper, economist Hyun Song Shin argued that financial markets are relatively calm and orderly most of the time. In the case of a crisis, all participants rush to decrease their risk, leading to heightened instability and potentially complete breakdown. Markets exhibited synchronous lateral excitation when “individuals react to what’s happening around them, and where individuals’ actions affect the outcomes.”20 It was a sophisticated version of yelling “fire” in a crowded theatre.

In 2006, central banks, responsible for financial stability, assessed the financial system as being healthy. They did not see any emerging threats. In August 2008, central bankers, regulators and bankers were reluctantly forced to admit that:

As late as the summer of 2007, virtually none of us...imagined that, as of July of 2008, financial sector write-offs and loss provisions would approach $500 billion...the underlying complexity and risk characteristics of certain financial instruments were so opaque that even some of the most sophisticated financial institutions in the world and their supervisors were simply caught off guard.21

The entire system was an accident waiting to happen. Charles Calomiris, an economic historian, wrote in 2008 that: “The most severe financial [crises] typically arise when rapid growth in untested financial innovations...[coincides] with...an abundance of the supply of credit.”22

Relying on the Zohar

Financial crises were increasingly the result of the toxic pathologies inherent in the financial system, rather than economic downturns, geopolitical events or natural disasters.23 Economic cycles became less pronounced as a result of government actions, improvements in information, monetary and fiscal policies. At the same time, risk increased, driven by the structure of markets, flawed regulatory regimes and volatile capital flows.

Trading shifted risk within the system in complex ways. While hedge funds and banks provided liquidity and dispersed risk, they placed large bets on the same event using different instruments increasing risk. The relationship between hedge funds and banks that financed and traded with them created risk concentrations. Pricing, risk management and valuation of instruments relied on very similar models that did not capture the behavior of the underlying market, asset price dynamics and limitations in trading liquidity and funding.

Risk managers with a “brain the size of a caraway seed and the imagination of a parsnip”24 slavishly used inadequate techniques. Like the philosoher of science Thomas Kuhn, financial markets persisted with flawed models, arguing that they worked in normal conditions and were superior to alternatives. David Einhorn compared risk systems to: “an airbag which works all the time except when you get into a crash.”25

Financiers were reluctant to use qualitative approaches that were inconsistent with their scientific self-image. As Benoit Mandelbrot, the creator of chaos theory, observed: “Human Nature yearns to see order and hierarchy in the world. It will invent it if it cannot find it.”26

Psychologist B.F. Skinner created “superstitious pigeons.” Unlike in normal experiments, he fed the pigeons with no reference to the bird’s behavior. Even though the food was given out on a fixed schedule, each bird developed its own superstitious behavior, trying to uncover a pattern associated with food. One pigeon turned counter-clockwise about the cage, another repeatedly thrust its head into an upper corner of the cage, while others developed a pendulum motion of the head and body. Financial models were like the behavior of the superstitious pigeons.

Mathematical finance lent credibility and false precision to the dismal reality of risk management. A South Vietnamese officer questioned about U.S. Defense Secretary Robert MacNamara’s application of quantitative methodology to the Vietnam War replied: “Ah ‘Les Statistiques.’ Your secretary of defense loves statistics. We Vietnamese can give him all he wants. If you want them to go up, they will go up. If you want them to go down, they will go down.”27

Mastery of risk had not enabled human beings to overcome the notion that the future was divine whim or chance. Financial economists and risk management just replaced oracles and soothsayers. Banks and regulators relied on the power of the Zohar, a 23-volume, $415 work essential to the study of the Kabbalah: “By simply possessing the books, power, protection, and fulfillment came into their lives.”28

Blind Capital

A wall of liquidity drove the global economy: “[There are] capital flows around the market from what feels like limitless sources—from CDOs, CLOs, hedge funds, private equity and recycled foreign trade surpluses.”29 Steven Rattner, founder of hedge fund Quadrangle, told The Wall Street Journal on June 18, 2007: “No exaggeration is required to pronounce unequivocally that money is available today in quantities, at prices and on terms never before seen in the 100-plus years since U.S. financial markets reached full flower.”30

But the new economy was a toxic mix of increasing debt, risk, speculation, and “unrealistic aspirations and the expectations that they can be fulfilled.”31 British clinical psychologist Oliver James noted that great swathes of the population “believe that they can become rich and famous.”32 Dinner parties reverberated with: “Did you hear how much they got for the house down the road?”33

Reinventing its traditional economy of fishing and geothermal energy, Iceland, a country of 330,000, became a global banking player—“Wall Street on the tundra.”34 Icelandic bank Kaupthing (meaning “marketplace”) aspired to be the Goldman Sachs of the Arctic. Icelandic firms owned Eastern Europe’s telecommunication firms, well-known UK high street retailers such as House of Fraser, Arcadia and Hamleys and much of the Nordic banking system. When Bakkavor, an Icelandic food company, purchased Geest, creating UK’s largest ready-made food company, Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson, the CEO, explained where the money was coming from: “It comes from Barclays Bank.”35

With local interest rates at an asphyxiating 15.5 percent, ordinary Icelanders borrowed Japanese yen, Swiss francs or euros at low rates to buy houses. Fishermen did the same, until financial profits overwhelmed piscatorial earnings. The risk of devaluation of the krona, Iceland’s currency, against the borrowing currencies was ignored. Writing about the Mississippi Company speculation of 1719/20, Matthieu Marais, an advocate in the Parisian Parliament, noted: “It is trade where you do not understand anything, where all precautions are useless, where the most enlightened spirit doesn’t see a flicker and which turns according to the designs of the Movement of the Machines. Yet all the fate of the Kingdom depends on it.”36

Prime Minister David Oddsson, a key architect of Iceland’s transformation, was heavily influenced by Friedman, Hayek, Thatcher and Reagan. He lowered taxes, privatized government-owned assets, reduced trade restrictions and deregulated the banking system. In 2005, Iceland even hosted a meeting of the Mont Pelerin Society, the free-market think tank associated with Hayek and Friedman.

Iceland was quintessentially American in its “can do attitude.” Anticipating Barrack Obama’s “Yes, we can!” call to arms, Sigurdur Einarsson, the CEO of Kaupthing, told employees of his then small brokerage firm: “If you think you can, you can.”37 Tony Shearer, CEO of Singer & Friedlander, an English bank, acquired by Kaupthing, observed: “They were very different. They ran their business in a very strange way. Everyone there was incredibly young. They were all from the same community in Reykjavík. And they had no idea what they were doing.”38

Iceland had absorbed the key lesson of the new economy: buy as many assets as possible with borrowed money because asset prices only rise. Between 2002 and 2007 Icelanders increased their ownership of foreign assets by 50 times. When the financial crisis hit, Americans could point to Iceland and say: “Well, at least we didn’t do that.”39

Rent Collectors

Warren Buffet tells a story about a soapbox orator speaking to a Wall Street audience about the evils of drugs. At the end, he asked if there were any questions. One investment banker asked: “Yeah, who makes the needles?” Now bankers made the needles and the most of the opportunity. In the virtual age, anonymous bankers set about shaping the modern world—or, at least, its economy. Banks grew in size, increasing their lending and growing their balance sheets.

Between 1980 and 2008, the total debt of U.S. financial firms grew from around 20 percent of GDP to slightly greater than 100 percent. In the United Kingdom, the total size of the banks reached more than 4 times the country’s GDP, well above the United States but also larger than other countries reliant on the financial services sector such as Switzerland and the Netherlands. In the 4 years to October 2008, RBS (formerly the Royal Bank of Scotland) tripled the size of its balance sheet to more than £1.9 trillion (over $3 trillion), 15 times the size of the Scottish economy and larger than the UK’s GDP of £1.5 trillion ($2.7 trillion). In Iceland, between 2003 and 2007, the assets of the three largest banks grew from a few billion dollars to more than $140 billion, “the most rapid expansion of a banking system in the history of mankind.”40

America made less but bought more from Germany, Japan, and China, paying with newly printed IOUs. As its financial sector grew, UK manufacturing fell from more than 30 percent in 1970 to 11 percent of the economy in 2009. The people employed in the sector fell to 2.6 million workers or 10 percent of the workforce from 6.9 million or around 28 percent in 1978. According to the World Intellectual Property Organization, UK ranked below North Korea in terms of number of patents granted.

In 2007, the U.S. financial sector’s share of domestic corporate profits reached a peak of 41 percent, up from 21 percent to 30 percent in the 1990s. Between 1973 and 1985 the financial sector’s share was below 16 percent. Between the early 1980s and 2007, the combined value of these firms grew from 6 percent to 23 percent of the stock market. Between 1996 and 2007 alone, the profits of finance companies in the S&P500 increased from $65 billion to $232 billion, or from 19.5 percent to 27 percent of the total. In tiny Australia, bank profits rose from 1 percent of GDP to 6 percent between 1960 and 2010, tripling in the last 10 years.

Compensation levels rose sharply, to 181 percent of the average for U.S. private industry. Between 1948 and 1982 they had been between 99 percent and 108 percent. In 2006 and 2007, Wall Street bonuses totaled $34.3 billion and $33 billion respectively, an increase from $9.8 billion in 2002.

Financiers earned large economic rents—excess earnings above the amount required to ensure adequate supply of the goods or services. Free markets and competition should reduce economic rents. But the structure of financial markets, especially the lack of transparency, ensured high profitability. Specialized products, combined with information and skill asymmetries between banks and customers, created profit opportunities. Investors hired advisers, who hired consultants, who hired fund managers, who hired other fund managers, who bought products from banks, who laid off the risk with other banks or investors. Everybody along the chain earned a share of the action.

There is no “try before you buy” with financial products. Marketed on the basis of past returns, complex and long-term in nature, financial products lend themselves to economic rent seeking. When fund management fees were reduced by migration to low-cost index tracking funds, investment managers tempted investors into new higher margin products, structured investments, private equity and hedge funds, with the promise of high returns. Simple derivatives were repackaged into complicated and opaque exotic structures to increase profit margins.

High rewards encouraged the best and brightest to sign up, helping create newer more complex products. Ragnar Arnason, a professor of fishing economics at the University of Iceland, found that: “Everyone was learning Black-Scholes.... The schools of engineering and math were offering courses on financial engineering.”41

Best in Best Possible World

All financial bubbles start with a convincing and plausible theory of “this time it’s different.” It may be new technology (railways, cars, computers, or the Internet) or new markets (China). People start to extrapolate boldly into regions where common sense has never gone before, leading to over-investment helped by easy money and excess credit. Rising debt drives up asset prices leading to even more debt that cannot be supported by values or income produced.

The system is underpinned by faith in the competence of legislators, regulators and the chattering classes—commentators, gurus and financial journalists. Faux theories, such as Alan Greenspan and Ben Bernanke’s Great Moderation, reassure investors that old problems have been overcome. Moral hazard increases as excessive risk taking and speculation become commonplace. There are increases in beezle42—fraud or embezzlement—as sharp people take advantage of the favorable conditions and abundance of money.

As Dr. Pangloss, professor of “metaphysico-theologo-cosmolo-nigology” in Voltaire’s Candide, knew: “All is for the best in the best of all possible worlds.” Bankers were the best of the best. Nick Sibley, former managing director of Jardine Fleming, predicted the result: “Giving liquidity to bankers is like giving a barrel of beer to a drunk. You know exactly what is going to happen. You just don’t know which wall he is going to choose.”43

Until 2007 prices went up, and everybody made money. In 1856 Walter Bagehot wrote:

At particular times a great deal of stupid people have a great deal of stupid money.... At intervals...the money of these people—the blind capital, as we call it—of the country is particularly large and craving; it seeks for someone to devour it, and there is a “plethora”; it finds someone, and there is “speculation”; it is devoured, and there is “panic.”44

Visiting the London School of Economics in November 2008, Queen Elizabeth asked why nobody saw the global financial crisis coming. The real reason why economists were unprepared was simple. In a wonderfully titled blog, “The unfortunate uselessness of most ‘state of the art’ academic monetary economics,” economist Willem Buiter pointed out that for decades economic research had become “haiku like,”45 preoccupied by its internal logic and aesthetic puzzles. It was largely uninterested in how the economy really worked. It completely ignored how the economy would work in times of stress and financial instability because such conditions were deemed impossible in the new age.46

In June 2009, Professors Tim Besley and Peter Hennessy drafted a letter to Her Majesty summarizing the views of the economic establishment. Many economists had apparently foreseen the crisis, merely failing to specifically identify the timing of its onset, specific dynamics and extent. The economists hoped to “develop a new shared, horizon-scanning capability so that you never need to ask that question again.”47

Nobody really understood how risky the economy had become or how it functioned. The economy grew and people prospered, as their houses and retirement savings increased in value. Company earnings rose every quarter. People talked about quick four-bagger and five-bagger returns (a four-bagger is four times or 400 percent return). As Walter Bagehot knew: “People are most credulous when they are happy...when money has been made.”48

In the film Transformers, a meditation on the dangers of advanced technology, a mobile phone turns into a homicidal robot. Advanced finance posed the same danger to the global economy.

In David Hare’s play The Power of Yes, a central banker identifies the moment the crisis hit the UK. At a celebratory opening night dinner for a conference celebrating the era of stability and confidence, everyone was complacent. At least, they were until one staff member reported to the Governor of the Bank of England that the imminent demise of Northern Rock was being reported in the news.49