18. Shell Games

In the new economy, central banks and bank regulators were all-powerful. In 2005, David Oddsson, the former prime minister of Iceland, became governor of Iceland’s Central Bank. Economist Brad DeLong mused: “It is either our curse or our blessing that we live in the Republic of the Central Banker.”1

In 1933, President Roosevelt argued for financial regulation:

The money changers have fled from their high seats in the temple of our civilization. We may now restore that temple to the ancient truths.... There must be strict supervision of all banking and credits and investments; there must be an end to speculation with other people’s money.2

Over time, the regulations were relaxed. Enacted to regulate the financial sector, the UK Financial Services Act 2001 specifically required the regulator “not to discourage the launch of new financial products” and avoid “erecting regulatory barriers.”3 Deregulation of financial markets now maintained the flow of money.

Central Bank Republics

Central bankers, led by Alan Greenspan, believed that lightly regulated markets promoted prosperity: “government regulation cannot substitute for individual integrity...the first and most effective line of defense against fraud and insolvency is counterparties’ surveillance.... JP Morgan thoroughly scrutinizes the balance sheet of Merrill Lynch before it lends.”4 In 2008, defending deregulated markets, Greenspan stated: “You can have huge amounts of regulation and I will guarantee nothing will go wrong, but nothing will go right either.”5

In his review of the global banking crisis, Lord Adair Turner noted that:

An underlying assumption of financial regulation in the U.S., the UK and across the world has been that financial innovation is by definition beneficial, since market discipline will winnow out any unnecessary or value destructive innovations. As a result, regulators have not considered it their role to judge the value of different financial products, and they have in general avoided direct products regulation, certainly in wholesale markets with sophisticated investors.6

It was a matter of faith:

Our soundness standards should be no more or no less stringent than those the market place would impose. If banks were unregulated, they would take on any amount of risk they wished, and the market would price their capital and debt accordingly.7

Capital held by banks and brokers against loss decreased, increasing their leverage. The definition of capital was expanded to include hybrid capital, debt ranking below deposits and senior borrowings. Cheaper than normal equity, hybrids avoided dilution of existing shareholders. Increases in debt and leverage reflected “improved financial flexibility...the results of massive improvements in technology and infrastructure.”8 Banks’ liquidity reserves, designed to cover withdrawal of deposits, were reduced, freeing up money for lending. The risk was ignored: “The lack of a spare tire is of no concern if you do not get a flat.”9

In 1999, commenting on the Asian crisis, Greenspan argued that the lack of well-developed financial markets in Asia had contributed to the problems. Economist Robert Wade disagreed:

[Greenspan] and other U.S. officials see it as imperative to make sure that the troubles in Asia are blamed on the Asians and that free capital markets are seen as key to world economic recovery and advance; the idea that international capital markets are themselves the source of speculative disequilibria and retrogression must not be allowed to take root.10

The Greenspan put ensured that at the first sign of trouble central bankers—“pawnbrokers of last resort”11—flooded the system with money, lowering interest rates to protect risk takers. The strategy ensured successive, larger blow-ups in financial markets in 1987, 1991, 1994, 1998, 2001, and 2007. Martin Wolf, the chief economics writer for the Financial Times, argued: “What we have [in banking] is a risk-loving industry guaranteed as a public utility.”12

Greenspan did not see any contradictions in the bailout of LTCM: “some moral hazard, however slight, may have been created by the Federal Reserve’s involvement. Such negatives were outweighed by the risk of serious distortions to market prices had [LTCM] been pushed suddenly into bankruptcy.”13 As English philosopher Herbert Spencer knew: “the ultimate result of shielding men from the effects of folly is to fill the world with fools.”

Games of Old Maid

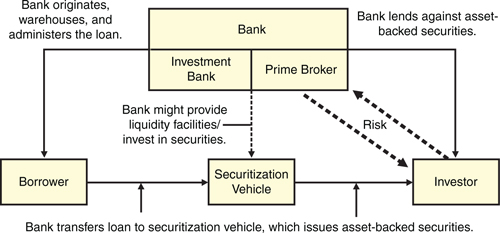

Central bankers’ assumption about securitization and derivatives reducing risk were wrong. Figure 18.1 shows how transferred credit risk finds its way back to the bank.

Figure 18.1. Risk transfer games

Where it sells risky loans, the bank may invest in the securities created, sometimes to reassure other investors. Banks also hold the loans until sold, exposing them to market disruptions. Banks provide liquidity, standby lines of credit, to SPVs to cover funding shortfalls. If the vehicle cannot fund, then the bank may be forced to lend against the assets that have supposedly been sold.

Risk also returns to the bank via the back door. Where a bank finances investors, such as hedge funds that use borrowing to increase returns, it is exposed to the securities lodged as surety. If the value of the securities used as collateral falls and the investor does not have the cash to meet the call for additional margin to cover the amount now owing, then the bank must sell the securities to recover the loan. Where illiquid structured assets created by the bank are used as collateral, they end up back on the bank’s books. As Charles Caleb Cotton observed in 1825: “There are some frauds so well conducted that it would be stupidity not to be deceived by them.”

One commentator accurately pointed to the regulators’ abject lack of understanding:

Alan Greenspan was mistaken in believing that the largely unregulated hedge fund industry can be effectively controlled by regulating creditors... Creditors can be just as prone to greed as the latest wizard of Wall Street, but they are often the last to understand the risks that would ordinarily help fear counterbalance greed.14

Protection Rackets

Markets increasingly relied on bond ratings, opinions of the likelihood of payment of interest and principal based on mathematical models using historical default experience. Ratings determined whether investors could purchase particular securities, the cost of raising money and the parties you could deal with. Eventually, central banks enshrined the role of ratings in banking regulations, using them to determine the amount of capital required to be held against bonds or loans.

Moody’s Investor Services (Moody’s), Standard & Poor’s (S&P), and Fitch controlled 95 percent of the ratings market. Moody’s and S&P’s combined market share was 80 percent. The columnist Tom Friedman pointed out the obvious:

There are two super powers in the world in my opinion. There’s the United States and there’s Moody’s Bond rating service. The United States can destroy you by dropping bombs, and Moody’s can destroy you by downgrading your bonds. And believe me, it’s not clear sometimes who’s more powerful.15

Forbes rated the CEO of one of the rating agencies as the 35th most powerful man, just below Saddam Hussein.

Credit ratings involve conflicts of interest—do agencies work for investors who use their ratings, the companies they rate or banks that pay them to rate issues? Originally investors paid subscription fees for ratings information. Today, 90 percent of revenues are from issuers wanting to be rated.

For rating straightforward corporate bonds, the agencies receive 0.03 or 0.04 percent of the size of the issue, with a minimum fee of $30,000 and a maximum fee of $300,000. For rating complex structured bonds, the agencies get paid more, 0.10 percent capped at $2–3 million. Securitization drove rapid increases in the revenues of rating agencies. In 2007, Moody’s revenues from rating structured securities were $900 million, an increase of over 5 times from $172 million in 1999, far in excess of fees from rating government, municipal and corporate bonds.

The rating business paid well, with Moody’s (17 percent owned by Warren Buffett’s investment company) showing a profit margin of over 50 percent. Glenn Reynolds, head of CreditSights, a research firm, called it: “As close to Shangri-La as you can get, at Microsoft-plus margins.”16 A cumbersome, slow approval process restricted new entrants, creating a lack of competition. Toronto-based Dominion Bond Rating Service took 13 years to obtain approval.

In 2000, when Moody’s became a public company, senior management received stock options and performance incentives. Senior rating agency staff, traditionally graduates who missed out on prestigious Wall Street jobs, now earned seven-digit salaries, up from the high-five or low-six levels. Protecting investors gave way to maximizing revenues. In a Freudian slip, one journalist referred to Fitch as Filch.

Stockholm Syndrome

In 1994 the agencies failed to anticipate the collapse of Orange County from derivative trading losses. Insufficient disclosure was the reason offered. In 1997, they failed to predict the financial collapse of Asian countries, blaming insufficient disclosure and lack of informational transparency. After Enron and WorldCom went bankrupt, they argued insufficient disclosure and fraud.

In 2007, Moody’s upgraded three major Icelandic banks to the highest AAA rating, citing new methodology that took into account the likelihood of government support. Although Moody’s reversed the upgrades, all three banks collapsed in 2008. Unimpeded by insufficient disclosure, lack of information transparency, fraud, and improper accounting, traders anticipated these defaults, marking down bond prices well before rating downgrades.

Rating-structured securities required statistical models, mapping complex securities to historical patterns of default on normal bonds. With mortgage markets changing rapidly, this was like “using weather in Antarctica to forecast conditions in Hawaii.”17 Antarctica from 100 years ago!

The agencies did not look at the underlying mortgages or loans in detail, relying instead on information from others. Moody’s Yuri Yoshizawa stated: “We’re structure experts. We’re not underlying-asset experts.”18 Jamie Dimon, the CEO of JP Morgan, later observed: “There was a large failure of common sense.... Very complex securities shouldn’t have been rated as if they were easy-to-value bonds.”19

As high rating levels were crucial for success and profitability, bankers frequently pressured the agencies. Taking advantage of different models used by individual agencies, bankers shopped around for higher ratings. One S&P employee compared the people rating mortgage-backed securities to hostages who have embraced the ideology of their kidnappers—the Stockholm Syndrome. At the 2005 annual off-site meeting, three members of Moody’s structured finance department, dressed as the Blues Brothers, performed an original song called “The Compliance Blues,” mocking the agency’s quality control team.

Lawyer David Grais identified the changed role of the agencies:

An analogy...is with the restaurant critic. If the restaurant critic dons his disguise and goes to the restaurant and eats dinner and writes a review, he’s clearly a journalist. But if he steps into the kitchen and samples the sauce and makes suggestions to the chef about how to correct the seasoning, and then comes back out and writes a review of the meal that he helped to create, he’s acting as something more than a journalist...journalists do not participate in the events that they cover...in structured finance the rating agencies were back in the kitchen.20

In October 2007, Raymond McDaniel, CEO, admitted that at times: “We drink the Kool-Aid.”21 American politicians described it as a “bone-chilling definition of corruption.”22

Free Speech

Rating anomalies emerged.23 Table 18.1 shows the percentage of CDOs that defaulted in the period till 2003. While no AAA-rated CDO defaulted, the 22 percent default rate for BBB CDO securities (investment grade) was not materially different from the 24 percent for BB CDOs (junk). Many investors can only purchase investment grade securities, but in a CDO the risks appear the same. Defaults on BBB CDOs were around ten times that for equivalent conventional securities.

Table 18.1. Actual CDO Default Rates

In 2010, Donald MacKenzie of the University of Edinburgh compared the actual defaults on mortgage backed securities against predictions based on typical models used by rating agencies. For AAA rated securities, the actual defaults were more than 12 times the model predictions. For securities with ratings AA, A, and BBB, the actual defaults were anywhere from 75 to over 300 times higher than the model estimates.24 Between November 2007 and May 2010, 93 per cent of all AAA securities in synthetic securitisations had their rating downgraded.

Facing criticism, chairman and chief executive Harold “Terry” McGraw, III defended S&P: “A couple of assumptions we made didn’t work out and we just totally missed on the U.S. housing recession.”25 Moody’s Brian Clarkson explained: “We were preparing for a rainstorm and it was a tsunami.”26 When criticized, the agencies claimed their ratings were opinions, protected under the U.S. constitution as free speech.

“Ratergate,” a 2008 SEC investigation, turned up embarrassing internal emails. “It could be structured by cows and we would rate it.” The analyst confessed to being able to measure “half” of a deal’s risk prior to providing a rating. Another wrote: “Let’s hope we are all wealthy and retired by the time this house of cards falters.” One analyst admitted: “We do not have the resources to support what we are doing now.”27 Pimco’s Bill Gross colorfully observed that the CDO ratings were a “tramp stamp” and the agencies were seduced by “hookers in six-inch stilettos.”28

Investors ascribed magical properties to the alphabet soup of letters, remaining willfully ignorant about how ratings are determined or their meaning. In 2010, Robert Rubin stated that “AAA securities had always been considered money good,” that is, no loss was likely.29

Stan Correy, an Australian journalist, was confused: “They have become both critic and chef in the big financial kitchens, but they say they’re really journalists and take no responsibility for their advice. [Credit rating agencies] are probably beyond the law, yet governments have said their advice is mandatory. Weird.”30

No Accounting for Values

Harvard professor Eddie Riedl told his MBA class that “Accounting = Economic truth + Measurement error + Bias.”31 Accounting was now mainly “measurement error” and “bias.”

Developed in the late fifteenth century by Venetian monk Luca Pacioli, double-entry accounting was not designed for modern finance. Robert Merton, the Nobel Prize-winning economist, thought that it was asking “a plough horse to gallop on a race track.”32 Accountants frequently resorted to Pacioli’s De viribus quantitatis, a treatise on mathematics and magic, describing card tricks, juggling, eating fire, and making coins dance. American comedian David Letterman noted: “There’s no business like show business, but there are several businesses like accounting.”

Modern accounting struggles to provide tolerably accurate, reasonably objective, and meaningful information about financial positions. Accounting standard setters admit that users of accounting statements untrained in the nuances find them difficult to follow. Users need experts to help them understand the information. Alan Greenspan noted that:

It has been my experience that competency in mathematics, both in numerical manipulations and in understanding its conceptual foundations, enhances a person’s ability to handle the more ambiguous and qualitative relationships that dominate our day-to-day financial decision making.33

He may be the only one who understands modern financial statements.

Mark to Make Believe

Financial statements relied on mark-to-market (MtM) accounting, using market values for assets and liabilities rather than original cost adjusted for impairment. Academics assumed: “Financial assets, even complex pools of assets, trade continuously in markets.” They advocated the use of models for valuation:

To provide estimates of the fair values of their assets.... Banks can similarly use models to update the prices that would be paid for various assets. Trading desks in financial institutions have models that allow them to predict prices to within 5 percent of what would be offered for even their complex asset pools.34

In practice, as few things had true markets, market value became fair value accounting.

Financial Accounting Standard Board (FASB) Standard 157 (FAS157), provided a three-level hierarchy of valuation (three levels of enlightenment). Level 1 required observable prices for identical assets or liabilities in active markets (true mark-to-market). Level 2 used observable inputs put through a model as actual prices for the instruments were unavailable (mark-to-model). Level 3 required subjective assumptions as observable inputs or prices were unavailable (mark-to-make-believe or mark-to-myself).

Fair value accounting gave financial institutions and auditors considerable latitude in valuing assets. During the boom, this helped create an illusion of high earnings and financial strength. In a letter to The Times dated July 27, 2010, a group of UK academics and accountancy experts wrote that: “the ‘fair weather’ model significantly overstated bank profits, resulting in excessive dividends. It also obscured true gearing and capital destructive business models. In ‘storm’ mode it accelerated and exaggerated losses, resulting in taxpayer-funded recapitalizations.”35

During the financial crisis, only government bonds, large well-known stocks and listed derivatives remained liquid. Valuation for anything else required a higher degree in a quantitative discipline, a super computer and a vivid imagination. David Goldman, a credit strategist, described quotes for credit default swap contracts:

The business looks like the window of a Brezhnev-era Soviet butcher shop. Mouldy scraps hanging in the window. Old women lining up at 4 a.m. to try and buy credit protection on General Motors. What are reported as trades are really ways to establish prices to satisfy the auditors.36

Dubious market prices drove real investment and credit decisions, through asset values, profits and losses, risk calculations, and the value of collateral supporting loans. A current market price of 85 percent for an AAA security does not mean that you will lose 15 percent. It is an estimate of likely losses if you sell today. In volatile markets, values deviate significantly from actual values if the security is held to maturity.

Prices are prone to manipulation. Banks may mark positions at high prices to prevent complex, illiquid securities being sold at a discount, and pushing down values. If the securities actually traded, then the lower market price would be used to value positions, increasing losses and margin calls for more collateral on already cash-strapped investors. Alternatively, a lower price is used to force margin calls and selling, allowing dealers to buy the assets cheaply.

The entity’s own credit risk was now required to be used to establish the value of its liabilities, resulting in gains for credit downgrades and losses for credit upgrades. If a bank has issued $100 bonds and the market price drops to $80 (80 percent), then it records a gain. During the financial crisis, banks recorded substantial profits from revaluing their own liabilities—bizarrely increasing profits as their financial condition deteriorated.

In volatile markets, instead of providing an accurate picture of the financial position, market value accounting increased volatility as behavior became linked by accounting disclosures. Coordinated actions of participants led to sharp movements in asset prices, distorting financial position and value, exacerbating uncertainty and destroying market confidence.

Market value accounting eliminated one market imperfection (poor information) magnifying another imperfection (illiquid markets). In 2008, with the capital markets frozen, a Congressional Oversight Panel noted that:

The risks troubled assets continue to pose...depend on how many troubled assets there are. But no one appears to know for certain.... It is impossible to ever arrive at an exact dollar amount of troubled assets, but even the challenges of making a reliable estimate are formidable.37

The ability to recognize earnings immediately really drove market value accounting. Tony Shearer, CEO of Singer and Friedlander, told the UK House of Commons that virtually all Icelandic bank Kaupthing’s stated profits were from inflated prices of assets: “The actual amount of profits that were coming from...banking was less than 10 percent.”38

Bankers paid themselves substantial bonuses on profits that were expected to show up in cash some time in the future—that is, if they showed up at all. In Lucy Prebble’s play Enron, Jeffrey Skilling explained that profits needed to be recognized when the deal was concluded: “Life is short. If you have a moment of genius [you] will be rewarded now.”39

Out of Sight

Banks and companies used special structures to park assets and associated funding off-balance sheet, reducing the firm’s size. Financial institutions moved assets to QSPEs (qualified special purpose entities), recording a sale and the amount received as revenue. Securitization and derivatives shifted assets off-balance sheet, but liquidity puts and standby funding arrangements meant that the risk remained with the bank.

Following the collapse of Lehman Brothers, a court-appointed examiner found that the investment bank used repos (repurchase agreements) to shift assets off-balance sheet.40 In a repo, the borrower sells an asset, simultaneously agreeing to repurchase it at an agreed price plus interest for funds advanced at a future date. Normally, a repo is treated as a secured loan. But where the securities are worth significantly more than the loan, the repo is treated as a sale.

Lehman did $50 billion of repo 105 (the assets were 105 percent of the loan) at the end of each quarter, reversing it a few days later. The repos reduced assets and debt, lowering Lehman’s leverage and risk. In March 2008, Erin Callan, briefly the CFO of Lehman Brothers, affirmed the firm’s commitment to “trying to give the group a great amount of transparency on the balance sheet.”41 At about the same time, Herbert McDade, a Lehman executive known as the firm’s balance sheet czar, referred to repo 105 as “another drug we’re on.”42 Banks reduced their balance sheets by as much as 40 percent over quarter ends, effectively hiding their leverage and risk from the world.

Off-balance sheet treatment relied on the fiction that the banks did not control the assets and the vehicles. In the financial crisis, the fiction evaporated as assets held by SIVs and securitization vehicles returned to the balance sheet from whence they came.

Creeping Crumble

Sir David Tweedie, head of the International Accounting Standards Board, criticized accountants as having “all the backbone of a chocolate éclair,” when facing pressure to massage client’s financial statements. He complained of “creeping crumble” when:

Auditors [were picked off] by investment bankers, selling a scheme that perhaps was just within the law to a client, persuading two major auditing firms to accept it whereupon it became accepted practice and QCs would tell a third auditor that he could not qualify [the company’s financial report] as the scheme was now part of “true and fair.”43

Market values were acceptable when there were gains, but everybody wanted historical or adjusted model prices when there were losses. The International Institute of Finance (IIF) proposed a return to using historical prices to facilitate stable valuations in order to increase market confidence. Goldman Sachs dismissed it as “Alice in Wonderland accounting.”

Resisting calls for changes in accounting standards, one accountant argued that: “It’s the market that needs to change, not the accounting.” French accountants concluded that “market prices [had been] squeezed by a crisis discount” and proposed adjusting the valuation using an “upgraded fair value” model for serious crises. The accounting regulator would arbitrate when the crisis discount was abnormally high, allowing a switch from market value to fair value based on a mark-to-model approach.44 The proposal highlighted French strengths first identified by Napoleon III: “We do not make reforms in France; we make revolution.”

Radical proposals retreated to the position before market value accounting. Instruments held to maturity would be valued at book value, adjusted for impairments and trading instruments at market. Accountants decided that it was better to manipulate the values and pretend that there were no losses in preference to inconvenient truths.

Standard setters unveiled a more pressing project, plain English accounting. To simplify the language of accounting, they proposed people who owe us money instead of debtors. Current assets would become assets we have at the present time. Liabilities would become where the money came from.

Sir David Tweedie outlined the heroic role of the accountant:

The accountant is an artist, but he has to portray his subject faithfully.... If the reporting accountant lacks integrity; if raw economic facts are unpalatable and smoothing devices are sought; if he fails to support fellow professionals who have carefully documented their view of the principle, researched the literature and sought advice and made an honest judgment; if regulators demand one answer and one alone, not those within a range; or if the profession constantly seeks answers for all questions—the reporting accountant will paint by numbers and deserve the rule-based standards he has requested. This will be the profession of the search engine, not one of reasoned judgment.45

Management by Neglect

Empty words like governance and oversight masked a lack of adult supervision of business and markets. A culture of benign neglect presided over increasing debt, greater leverage, higher risk, lower capital, and accounting fudges.

Financial statements were filled with page after page of disclosure about meetings of audit and risk committees—how often they met, who attended. It was form over substance, a case of ticking boxes. A character in David Hare’s play The Power of Yes describes it like a fast-moving vessel that everyone thinks is running fine, but no one seems to care that it’s like the Titanic heading toward an iceberg.46

Senior management rarely understood the spells and potions cast by the financial alchemists in their employ. Elite senior securitization and exotic derivative wizards were reluctant to let others in on the lucrative magic and voodoo they practiced. Managers needed Roosevelt’s March 12, 1933 fireside chat on banking, which, according to Will Rogers: “made everyone understand it, even the bankers.”47

Few senior bankers understood transactions outside their expertise. Even then, their knowledge was frequently dated. Today, a 55-year-old rarely understands a 25-year-old. In banking, the rapid rate of innovation and change meant that a 35-year-old did not understand a 30-year-old, and the 30-year-old did not understand a 25-year-old. John Gutfreund, former CEO of Salomon Brothers, told Michael Lewis that CEOs could not oversee large financial institutions: “I didn’t understand all the product lines and they don’t either.”48

Vikram Pandit, CEO of CitiGroup (replacing Prince), had multiple degrees from Columbia University and had run his own hedge fund. When MBIA, a bond insurer, was in trouble, Pandit was stunned to discover that CDS contracts insuring Citi’s portfolio of MBSs only paid out if there were actual losses, not unrealized mark-to-market losses.49 Richard Fuld, CEO of Lehman, had traded simple instruments that did not prepare him for the firm’s complex transactions. The Lehman CEO had no knowledge of repo 105 as he did not use a computer and did not have the ability to open attachments on his BlackBerry.50 Jamie Dimon, CEO of JP Morgan, noted that: “It’s very dangerous to fly at 40,000 feet if you don’t have the ability to drill down and have deep knowledge of the company and its various businesses.”51

CitiGroup’s senior managers blamed their disastrous foray into mortgage securitization on advice from external consultants. They created small inner cabals to mask their insecurity and inability to control the underlying business.

It was management by deal—buying and selling businesses, creating fiefdoms run by trusted associates. When Bank of America (BA) suffered large losses, CEO Ken Lewis confessed that: “I’ve had all the fun I can stand in investment banking right now.”52 Lewis said that he would not use BA’s petty cash to buy an investment bank. Shortly afterward BA purchased Merrill Lynch, Lewis deciding: “I like it again.”53 Lewis predicted that the acquisition would be a thing of beauty.

The only strategy was follow the leader. Richard Posner, U.S. federal judge, argued that competition and fear of falling behind meant that managers had no choice.54 Former CitiGroup chairman Sandy Weill candidly admitted that: “If you look at the results of what happened on Wall Street, it became, ‘well, this one’s doing it, so how can I not do it, if I don’t do it, then people are going to leave my place and go some place else.’”55 In The Power of Yes, the character David Freud summarizes it. When people tell you that they can get higher returns and more money, it is difficult to refuse. People begin to think that there is something wrong with you.56

Senior management frequently did not seem to have a good grasp of what was going on in their own firm. John Thain, a former Goldman Sachs executive and head of the New York Stock Exchange, replaced Stan O’Neal at Merrill Lynch. Asked about Merrill’s need for capital, on January 15, 2008, Thain stated that “[recent capital raisings] make certain that Merrill is well-capitalized.” On March 8, 2008 Thain reiterated: “Today I can say that we will not need additional funds.... We will not return to the market.” On March 16, Thain went further: “We have more capital than we need, so we can say to the market that we don’t need more injections.” In April 2008, Merrill Lynch issued $9.55 billion of preferred shares to raise capital. On July 17, 2008 Thain returned to the same theme: “Right now we believe that we are in a very comfortable spot in terms of our capital.” Later, in July 2008, Merrill would sell its stake in Bloomberg for US $4.5 billion and issue $8.5 billion in shares to raise capital.

After hearing testimony from senior CitiGroup executives, Phil Angelides, chairman of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, remarked: “One thing that is striking is the extent to which senior management either didn’t know or didn’t care to know about risks that ultimately helped bring the institution to its knees.”57

Directing Traffic

Compliant nonexecutive boards of directors, hand-picked by CEOs, were even further removed from the action. Taking their independence seriously, they chose to function without any knowledge of the industry, firm, or what was actually going on.

Former U.S. President Gerald Ford, a member of the Lehman Brothers board, asked about the difference between equity and revenue.58 Robert Rubin, vice-chairman of Citi, argued that: “A board cannot know what is in the position books of a financial services firm. You cannot know the granularity of the positions.”59 Upon joining the Salomon Brothers Board, Henry Kaufman found that most nonexecutive directors had little experience or understanding of banking. The board reports were “neither comprehensive...nor detailed enough...about the diversity and complexity of our operations.” Nonexecutive directors relied “heavily on the veracity and competency of senior managers, who in turn ...re beholden to the veracity of middle managers, who are themselves motivated to take risks through a variety of profit compensation formulas.”60

Kaufman later joined the board of Lehman Brothers. Nine out of ten members of the Lehman board were retired, four were 75 years or more in age, only two had banking experience, but in a different era. The octogenarian Kaufman sat on the Lehman Risk Committee with a Broadway producer, a former Navy admiral, a former CEO of a Spanish-language TV station, and the former chairman of IBM. The Committee only had two meetings in 2006 and 2007. AIG’s board included several heavyweight diplomats and admirals; even though Richard Breeden, former head of the SEC told a reporter: “AIG, as far as I know, didn’t own any aircraft carriers and didn’t have a seat in the United Nations.”61

Under-resourced, under-skilled, and under-paid, regulators struggled to enforce legislation. Emasculated by lack of power and will, regulators resembled the unarmed policeman in a Robin Williams’ sketch trying to apprehend a fleeing suspect with the exhalation: “Stop! Or...I’ll shout stop again!”

Shown the exemplary returns of the Madoff fund, Harry Markopolos, an analyst at a small Boston firm, detected a telltale funny smell. Unraveling the secrets of Madoff’s money machine, he found the world’s largest Ponzi scheme. Motivated partly by the possibility of a bounty for whistleblowers, Markopolos tried on no less than five occasions to have the SEC investigate Madoff.

The SEC’s failure to follow up and take any enforcement action, in Markapolos’ view, was driven by ignorance, incompetence, arrogance, and unwillingness to take on a non-executive former chairman of NASDAQ and industry grandee. Markapolos observed that the SEC was “overlawyered... poisoned by lawyers.... If you can’t do math and if you can’t take apart the investment products of the 21st century backward and forward and put them together in your sleep, you’ll never find the frauds on Wall Street.”62

When things were going well, regulators favored self-regulation, which bears the same relationship to regulation that self-importance does to importance. In Holidays in Hell, P.J. O’Rourke provides an example of self-regulation. At a Syrian hillside roadblock, the soldier wants to search the trunk of a car. Told that the hand brake is faulty, the soldier volunteers to sit in the car holding the brake pedal while the driver opens the trunk. “Is there any contraband in there?” he inquires of the driver.63

When problems arose, regulators switched to a different plan. At a different roadblock, P.J. O’Rourke observed a soldier searching a rear-engined VW Beetle for stolen goods. Opening the luggage compartment in front and failing to find anything, he searches the trunk. Finding the engine, the soldier triumphantly exclaims: “You have stolen a motor...you have just done it because it’s still running.”64

A shell game is a confidence trick used to perpetrate fraud. It requires three shells and a small, soft round ball, about the size of a pea. The pea is placed under one of the shells; then the shells are shuffled around quickly while the audience bets on the location of the pea. Through sleight of hand, the operator easily hides the pea, undetected by the victims. Risk transfer, ratings, and accounting standards were the shell games of financial markets. Central bankers, regulators, rating agencies, accountants, managers, and directors played the game, over the years.