Chapter 2. Investment Becomes an Industry

Brian: “You’re all different!”

The crowd: “Yes, we ARE all different!”

Man in crowd: “I’m not.”

The crowd: “Ssssh!”

Monty Python’s Life of Brian

Investment has been institutionalized. Shares are now mostly bought and sold by institutions on behalf of someone else, not by individuals. Investors are judged by league tables, with a priority to maximize the amount of funds they manage rather than to make the biggest investment returns. With everyone trying to match the others, rather than stick out from the crowd, this drives them into “herding” behavior—and bubbles form where the herd goes.

What are investment managers paid to do? You might answer that they are paid to take their clients’ money and make the best return they can, or to beat the market. But in fact, they are mostly paid to maximize the assets they have under management (rather than profits). Investment managers generate fees as a percentage of the amount of money they manage, so their greatest fear is that clients will pull money from the fund, not that the fund will perform badly. This has a huge impact on the way our money is invested; when motivated by this fear, managers try to do the same as everyone else instead of standing out from the crowd. Such behavior directly leads to bubbles.

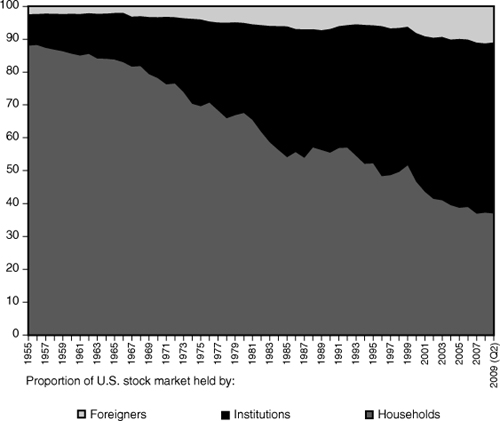

It was not always that way. Not long ago, the U.S. stock market was almost entirely controlled by individuals and their families. According to the Federal Reserve, 90 percent of U.S. stocks were in the hands of households in 1952. As Figure 2.1 shows, by the end of 2008, they held less than 37 percent, while institutions held the rest. Stock market investing was once a game for wealthy individuals investing on their own account, but it is now an industry.

It is easy to see how this happened. As the post-war Baby Boomers grew up, they put ever more money into generous public and corporate pension plans, which invested it in stocks. Companies set up to manage pension money offered their services directly to the public through mutual funds—big pools that take money from investors and invest it, with share prices that rise or fall in line with the value of fund’s portfolio of stocks.

All of this makes sense. Investing in stocks is difficult and small savers need professionals to manage that money for them. But the investing “principals”—the savers trying to fund their retirement—have been separated from their “agents,”—the fund managers who run their money. Decisions by those agents, not the principals, now drive the market. The incentives they face push them to move together in and out of particular investments, and this helps inflate bubbles. If there is any single factor to explain the newfound propensity to form bubbles, it is this.

Like everyone else, investment managers respond to the way they are judged, and since the mid-1960s, they have been subjected to strict comparisons with their peers. Savers can find out easily on the Web how a fund ranks compared to its peers over the last few days or over many years. The trustees who control pension funds rely on a few global consulting firms for advice, and those consultants in turn are driven by league tables.

In theory, this should spur managers to do better than the rest, but in fact, it encourages herd behavior. Like wildebeest on the savannah, fund managers try to do the same as each other, not stand out from the herd. There is safety in numbers.

To illustrate how these twisted incentives work, let us look at the Fidelity Magellan Fund, which was launched in 1964 and is in many ways the model that the modern investment industry still follows. Fidelity aggressively advertised the great returns it made under Peter Lynch, its manager from 1977 to 1990. For example, in the 20 years from 1976 to 1996, Magellan gained 7,445 percent—far in excess of the S&P 500, the main U.S. stock market index, which gained only 1,311 percent.1 After turning Lynch into a household name, Fidelity exported the formula, building in the UK on the back of the great track record of its star manager Anthony Bolton.

By the mid-1990s, Magellan was worth more than $50 billion, and Fidelity as a whole accounted for as much as 15 percent of each day’s trading on the New York Stock Exchange. The problem for Jeffrey Vinik, Magellan’s manager in 1995, was that Magellan was too big to make money the way it had done in the past. Sniffing out bargains in small stocks no longer helped. For example, if Magellan were to buy up all the stock of a company worth $100 million (an expensive operation in itself), and it doubled to $200 million, this would only grow the overall fund by 0.2 percent.

Magellan could not outperform its peers like that; it had to make bigger bets. And so in 1995, with the stock market rising, Vinik took about one-fifth of his portfolio out of stocks and put it into government bonds, in a bet that equities would soon fall. Instead, the stock market continued to boom, and the bonds killed Magellan’s relative performance (although it kept growing thanks to the money it still held in stock). At its worst in 1996, its performance over the previous 12 months ranked it as number 590 out of 628 U.S. mutual funds aiming for growth from equities. Investors responded and for 14 consecutive months, as markets boomed, they pulled their money out.

Relative performance swamped everything else. Morningstar, a powerful U.S. fund-rating group, ranks all funds from one to five stars. In 1996, funds with five and four stars, making up less than one-third of all funds on offer, accounted for about 80 percent of all new money being invested. To lose such a high ranking by making a big bet like Vinik’s and getting it wrong was career suicide.

Within months of making his bet, Vinik left Fidelity (and went on to have a brilliant second career running his own much smaller fund).2 Robert Stansky, his successor (a former researcher for Peter Lynch), sold the bonds and bought big technology stocks instead. Technology was in vogue at the time, so it was hard to beat the market by much by investing in them. But that was not the point; the priority, if you do not want to lose your clients, is to avoid embarrassment. Holding the same stocks as everyone else means that if you lose money, all your competitors will do the same—which is much less damaging than losing out, Vinik-style, when everyone else is prospering. There is safety in numbers.

In 1997, Magellan closed its doors to new investors, admitting that the big flows of money were making it harder to perform. In 1999, it became the first mutual fund to hold more than $100 billion. That recovery, though, was rooted in doing what everyone else did, rather than in being different.

For Vinik, and other investment managers, size was the enemy of performance. And yet for managers, if not their clients, size is more important. Assets under management, not performance, determine how much they are paid. Thus it is hard to stop accepting new money from investors, as it means turning down revenues and profits. But letting funds grow too big encourages herding, which leads to bubbles. When investors poured money into Internet funds in the late 1990s, or into credit investments in 2006 and 2007, managers had to choose between putting more money into those investments, even if they thought them too expensive, or losing clients. Mostly, they chose to keep clients and kept buying—and as they bought, they pushed up prices, or inflated bubbles, even more.

Magellan also shows the dangers of standing out from the crowd. If Vinik’s bet on a stock market fall had worked out, he might have attracted some more money. But often the response of pension funds’ consultants when this happens is to take money out of recently successful funds so that they do not become too big a part of the portfolio. Meanwhile, of course, he ran the big risk of losing funds if he was wrong. The incentives on him were asymmetrical, with limited upside for a correct decision and severe downside for a mistake.

Other managers had the same problem. Jim Melcher, a New York fund manager, saw that Internet stocks were in a bubble in the 1990s, avoided them, and lost about 40 percent of his investors as a result. “We see it time and time again, especially in tough times,” he said. “Major investors act like a flock of sheep with wolves circling them. They band closer and closer together. You want to be somewhere in the middle of that flock.”3

Another problem was that by investing in bonds, rather than sticking to its customary stock-picking, Magellan had done something that investors had not expected. Savers wanted their managers to behave predictably. Moreover, brokers, sales representatives, and consultants, who controlled flows of money, want funds to stay within their assigned roles. By advising clients to spread their assets between different funds and shift them periodically, they can justify their existence.

As time went by, big mutual fund companies gained business by rigorously segmenting their funds, even if it encouraged managers to go against their better judgments and go with the herd. For example, a fund holding large companies was expected to maintain “style discipline” and not buy smaller companies, even if its manager thought smaller stocks would do better—a policy that again forced managers to crowd unwillingly into assets they thought were overpriced.

Magellan also illustrated that funds are judged and ranked based on short-term performance. Vinik’s timing in 1995 was wildly off, as the stock market did not peak until 2000. Judging his move into bonds after 10 or 15 years, after two stock market crashes, it did not look so bad; but there is a human tendency to be swayed by recent performance and to expect it to continue. Clients tend to put their money into funds that have done well recently, often buying at the top and selling at the bottom.

Attempts to time turning points in the markets can be a professional kiss of death. Just look at the roll call of managers who predicted the collapse of Internet stocks, probably the biggest stock market mania of all time. Paul Woolley, who managed the UK operations for the large U.S. fund manager GMO, was rewarded by sweeping redemptions. He is now a professor at the London School of Economics, where he used his money to endow the Centre for Capital Market Dysfunctionality. The late Tony Dye, once head of the London fund manager UBS Phillips & Drew, earned himself the nickname of “Dr. Doom” and lost his job in February 2000, weeks before the bubble burst.4 They were proved right by history, but they would have been better off if they had gone with the herd and stayed in stocks. The same is true of the (very few) fund managers who stayed away from the credit bubble before the implosion of 2007 and 2008.

While funds were restricted to stocks, herding manifested itself in manias for particular kinds of stocks—conglomerates in the 1960s, technology stocks in the 1990s, and banking stocks in the middle of the 2000s. As funds widened to include different assets, including commodities and foreign exchange, and cover most of the world, the herd started to move across the globe, leaving ever larger and more synchronized bubbles behind them.

Indexes guided them on their path.

In Summary

• Institutionalized investment pushes investors to move in herds: Paying fund managers a percentage of the assets they manage and judging them against peers encourages them all to do the same thing.

• Solutions might include paying a flat rate and finding new benchmarks based on skill.