Chapter 13. Dot Coms and Cheap Money

“People still place too much confidence in the markets and have too strong a belief that paying attention to the gyrations in their investments will someday make them rich, and so they do not make conservative preparations for possible bad outcomes.”

Robert Shiller in Irrational Exuberance

The dot-com boom was the biggest stock market bubble in history—the culmination of decades of cheap money, moral hazard, irrational exuberance, and the herd-like behavior of the investment industry. The response to it prompted the rise of hedge funds and speculative excesses in credit and housing—preconditions for a broader super-bubble.

On November 13, 1998, a few weeks after the LTCM rescue, a start-up company called theglobe.com floated on the NASDAQ stock market. It ran an online community for young New Yorkers with forums such as Harmless Flirts and Soul Mates and a Hot Tub chat room. Everyone wanted to buy. Its shares were offered that morning at $9, and by mid-morning, they were trading for $97 a piece—a rise of 866 percent in two hours.

This insane rush to buy up an obscure Web site that had yet to make a profit showed that the money the Fed had pumped in to the system to revive the banking and credit sectors after LTCM was instead gushing toward the technology sector, which was already overheated. There was little that could be done to redirect the money. Cutting interest rates stimulates lending across an economy, so it was inevitable that investors would put the money into sectors with growth prospects. Thus low rates to save Wall Street created a bubble in tech stocks.

The NASDAQ boom had other sources of support. The world spent 1999 in the grips of the “Y2K” scare, the fear that computers would stall and shut down when “99” turned to “00” on their internal clocks. The Fed therefore made money available to ensure that such a computer crash did not block bank clients from their money. The bottom lines for the market were cheaper money and more investment in tech stocks. After the millennium turned, without incident, there was one last buying rampage, as NASDAQ stocks moved into a classic investment bubble. Once again, the logic was “safety in numbers.” Buy enough Internet start-ups, the logic went, and you would catch a winner or two. They would make you whole for the losses you made as all the others went bust.

There was only so far this argument could go. Google, which proved to be the greatest Internet winner, did not go public until years after the dot-com bubble burst. There was nothing to guarantee that snapping up every new company would yield a long-term winner. But in that environment, almost any start-up could raise funding. Perhaps best remembered is pets.com, an online seller of food and materials for pets, whose omnipresent television advertising featured a dog glove puppet. It went public at $11 per share in February 2000, spent $103 million on sales and marketing—$179 for every customer who ever bought from the site1—and then announced an “orderly wind down of its operations” nine months later when its share price had fallen to 9 cents.

Web retailers with little idea how to make money now symbolize the era. But even companies with a future were ridiculously overpriced. Cisco Systems, which dominated the market in routers that deliver the Internet to computers, became the biggest company on earth by market value, trading for almost 200 times its most recent earnings. Its share price was $80. Its profits and revenues grew thereafter, yet its share price in early 2010 was $23.

All of this looked as ridiculous at the time as it does now—but nobody had an incentive to blow the whistle on the mania while prices were still going up. When the bubble burst, it did so suddenly and with no obvious cue. On March 10, 2000, a Friday, the NASDAQ reached a peak of 5,132 and suddenly started to fall. After a weekend to think about it, traders sold on the following Monday morning, and from there the fall was swift and almost uninterrupted. When the NASDAQ came to rest more than two years later, it had lost 79 percent of its value.

What happened? Research reports had begun to emphasize companies’ “burn rates,” or how fast they were burning through their cash. Traders who had previously demanded losses from companies—as this showed that they were investing in new opportunities—finally began to think of their underlying economics. Meanwhile, stock exchange rules barred executives who floated their companies from selling all their shares initially. They were required instead to abstain from selling for a while and watch their fortunes grow on paper. Most companies had only floated a small percentage of their equity when they came to market, and the scarcity helped push up the price. Once the founders started trying to sell, there was in a sense a true market in their shares for the first time. This showed that their true price was much lower.

This was one of history’s most absurd investment bubbles and deserves a place beside the seventeenth century Dutch tulip mania. But it was not clear how much impact it would have on the general economy. Many mutual fund investors had only bought in near the top and were left with big losses. And the mania-directed money went into buying advertising for unimaginative Web sites when it could have been invested more productively. But many of the fortunes that were written off had only ever existed on paper. Dot-com millionaires barely had time to spend their wealth before it vanished. The United States went into a recession in 2000, but it was shallow—the briefest since the war. The economies of Western Europe survived without a single quarter of contraction. And the implosion of pets.com and the rest had little impact on other markets—prices of credit, commodities, and foreign exchange were barely affected.

However, Alan Greenspan and the Federal Reserve had their eyes on the economic disasters that had hit after the last two comparable stock market bubbles burst—in the United States in 1929 and in Japan in 1990. Worried that consumers’ losses in the stock market would prompt them to spend less and drag the country into deflation, they cut rates. After the September 11 terrorist attacks of 2001, which killed 3,000 and brought down the twin towers of the World Trade Center, and closed down the U.S. stock market for a week, the need to act seemed all the more urgent. The Fed cut its target lending rates to a historic low of 1 percent and left them there.

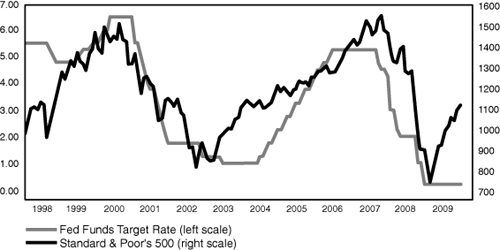

As with LTCM, after the market got into trouble, the Fed was there to bail them out with lower rates. In the options market, a “put” option gives a buyer the right to sell a stock at a fixed price. It ensures that someone else will have to take the pain for you if the price falls to a certain level. Now, traders talked openly of the “Greenspan Put” and the Fed’s credibility—vital in a world no longer anchored to gold—came into question for the first time in two decades. As Figure 13.1 shows, the Fed’s behavior in this period certainly made it look as though they would cut interest rates if ever the stock market fell. Traders took note, and stock markets turned around in 2002, when they still looked expensive by historical standards, and then started to rise. Investors’ confidence, even after an epic stock market bust, was higher than ever.

Figure 13.1. The Greenspan Put? The stock market leads the Fed.

The victors, ironically, were hedge funds. The NASDAQ crash was a perfect marketing aid for them. Some had actively bet against the bubble by selling short. Others had strategies that did not depend on the stock market and had flourished amid the anxiety from 2000 to 2002. In the first three years of the decade, the S&P 500 lost 9.1 percent, 11.9 percent, and 22.1 percent, respectively. Meanwhile, hedge funds (as measured by Hedge Fund Research, a big Chicago-based research group) gained 4.98 and 4.6 percent before succumbing to a small loss of 1.45 percent in 2002.2

Institutions’ urge to “chase performance” remained in place. Hedge funds not only appeared to guard against risk; they also made more money than anyone else. Money poured in. Big pension and endowment funds wanted a piece of the action. In 2002, more than $99 billion came into the industry—at the same time that small investors, shaken by the market falls, were pulling $24.7 billion out of mutual funds. Once a phenomenon of the Connecticut suburbs of New York, hedge funds colonized London’s Mayfair and established bases in Asia.

The number of funds proliferated. When LTCM went down in 1998, there were 3,325 funds; by 2007 there were more than 10,000. Traders working for banks would set up their own hedge fund to do the same thing for more pay and banks happily accommodated them, giving them room on the trading floor and research for some starting ideas. Generally, new funds planned to invest using strategies that others were already using. They followed similar models, generally based on the theories coming out of academic finance, as synthesized for them by the research departments of big banks, and this led them to the same investments.

In 2005, after four years of persistent inflows, the entire hedge fund industry was worth more than a trillion dollars for the first time. Two years later the industry’s assets would peak at more than $1.8 trillion. But this far understated their true power in the market because of their leverage; their true buying power was probably five or six times this much. And they tended to trade furiously, making them far more influential over the day-to-day direction of markets than mutual funds.

The guard had changed again. If the stock market had once been the province of amateurs and then belonged to mutual funds and big institutions, after the NASDAQ crash it was hedge funds that drove prices each day. This was significant because hedge funds, like mutual funds, tend to move in herds. But these herds could move much more widely, as they did not operate under tight remits, and could switch minute by minute between different asset classes and countries. This made them a huge force for interconnectivity between markets. Their use of leverage meant that they might well be forced to sell in haste if their bankers ever got anxious about their ability to repay their loans.

There was another problem. Hedge funds rely on exploiting trends and inefficiencies. With so many funds now leaping into action, inefficiencies disappeared fast. Like mutual funds, they found that size, or at least the number of funds, was the enemy of performance. So they moved quicker, used more leverage, and looked further afield for profits, driving trends as long as they could and throwing money at mispriced securities. Banks were happy to lend to them, generating fees in the process.

None of this helped the entrepreneurs who had briefly been multimillionaires before the NASDAQ bubble burst. By November 2009, shares in theglobe.com, which traded at $97 per share on its debut in 1998, were available for 0.19 cents each. Meanwhile investors needed a new bubble, and they would find it once more in the emerging markets.

In Summary

• The NASDAQ crash of 2000 was a historically extreme event. Rather than allow the U.S. stock market to endure a collapse on the scale seen after earlier bubbles, the Federal Reserve decided to cut rates. This became known as the Greenspan Put.

• Hedge funds made gains during the crash, and this helped them attract new money from investors and rise to dominate the market. Cheaper rates from the Fed helped them boost their returns with leverage.