Chapter 14. BRICs

“Recession-Plagued Nation Demands New Bubble to Invest In”

Headline in www.theonion.com satirical newspaper, July 14, 2008

By rebranding the emerging markets the BRICs (for Brazil, Russia, India, and China), Goldman Sachs ignited a fresh boom. The money pouring into the emerging markets tied them more closely to other stock markets and to commodity markets, as the BRIC stock markets were driven by commodity prices.

“The world needs better economic BRICs,” proclaimed Jim O’Neill in November, 20011. Goldman Sachs’s chief international economist was making an argument about economic summitry and global politics. He thought the four biggest emerging nations—Brazil, Russia, India, and China—should join major economic decision-making bodies. They were already as big as some of the G7 group of industrialized nations—the United States, Japan, Germany, UK, France, Italy and Canada—whose leaders steered the capitalist world. He showed that they were almost certain to grow bigger. With the world still reeling from the 9/11 terrorist attacks, he was arguing for a sensible realignment in the way global economies were coordinated.

He failed. The BRICs did not take their place at the world’s major economic summits until 2009. He succeeded, however, in giving the tired “emerging markets” brand a new lease of life and sparking another gush of money in their direction that also distorted the markets for commodities and foreign exchange.

O’Neill was an economist, not an investment strategist. But the BRICs immediately caught on as an investment strategy. They had a catchy acronym, and eye-catching growth estimates. (“China,” O’Neill said, “could overtake Germany by 2007, Japan by 2015, and the United States by 2039. India’s economy could be larger than all but the United States and China in 30 years.”) The investment industry needed new products after the dot-com bust and the BRICs met that need.

It led to another big idea: “decoupling.” Emerging markets largely relied on exporting to the West for their growth. Now, maybe the BRICs would grow by investing in their own infrastructure and catering to the demands of their own growing middle classes. As they built their highways and fed their people, they could “decouple” and grow even if the West was in recession. That promised the holy grail of uncorrelated returns.

Each of the BRICs had plausible stories to tell to investors. More prosaically, after the 1990s crises, emerging markets were dirt cheap. MSCI subsequently started a BRIC index and calculated how it would have performed going back to 1995. In the autumn of 2001, as O’Neill wrote, it was more than 40 percent below where it had been six years earlier.

The BRICs also had luck on their side. Brazil had a presidential election in 2002. Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, leader in the polls, was a veteran union leader. Money poured out of the country as investors took fright at the prospect of an apparent radical taking over. On the eve of his election, BRICs were down 55 percent from their level of 1995, while Brazilmain stock exchange, the Bovespa, was down 80 percent. Brazilian stocks could be bought for just eight times their earnings—at a time when stocks in the United States traded for 45 times their earnings. When Lula took office, he soon showed himself to be a pragmatist and this spurred an epic emerging market buying opportunity. Anyone who did enough detective work in Brazil could have seen that Lula was not the ogre that many feared and made a killing. But that kind of old-fashioned, on-the-ground detective work was going out of fashion. Instead, “BRIC investing” saw investors herd into index funds as the market took off.

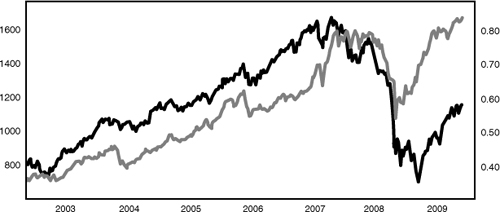

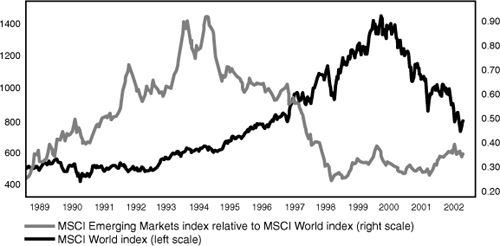

The main driver for these flows of money, whether Western investors realized it or not, was the balance between optimism and pessimism in the West. The logic of decoupling should be straightforward—if emerging markets do well even if times are harsh for the West, then they will be most appealing, relatively, when investors are anxious about the West. But the behavior of MSCI’s indexes for the developed world, emerging markets, and the BRICs showed that the opposite was the case. The better the World Index of developed countries did, the more the emerging markets and BRICs outperformed them. If the World did well, BRICs did even better; if the World did badly, BRICs did even worse. Figure 14.1 shows the ironclad relationship that lasted from the beginning of the BRICs boom through to the darkest days of the 2008 crisis. Far from decoupling, emerging markets had coupled to the rest of the world more than ever before. This was a new development—in the 1980s, their performance had been almost totally unrelated, while the 1990s saw a bull market in the West and crisis in the emerging markets (see Figure 14.2).

Figure 14.1. After the BRICs: emerging markets move on sentiment in the West.

Figure 14.2. Before the BRICs: emerging markets set their own pace.

How did this happen? The BRIC boom was driven by the risk appetites of fund managers and their tendency to move in herds. When investments at home were going well, Western investors had greater tolerance for risk, so funds crowded into the BRICs. When things got worse at home, they got out quick.

Fresh financial innovations helped this. Most emerging markets investing was done through funds that were ultimately linked to an index. And BRICs were ideally suited to the latest new financial products—exchange-traded funds, or ETFs. These are index funds holding a portfolio of shares that aim to match an index but that can be traded on stock exchanges like individual stocks. Their prices change by the minute, and they can be traded swiftly.

The first ETFs were created early in the 1990s, but they only caught on a decade later. In 2000 and 2001, as stocks crashed, ETFs’ assets increased fivefold. From there their growth was rapid, encouraged by stock exchanges that were going public and launching themselves as profit-making concerns, after years of being run as mutual cooperatives.

ETFs are a great idea. They make investing both easier and, for many, cheaper. The problem, as the BRICs boom shows, is the behavior they encourage. Jack Bogle, the inventor of the index fund, contemptuously calls ETFs “a traitor to the cause of classic index investing.” “Surely,” he argued, “using index funds as trading vehicles can only be described as short-term speculation.”2

Producing index funds that can trade minute by minute on an exchange could only encourage active trading and attempts to beat the market, he argued—the antithesis of his notion of passive index investing. Like a Purdey shotgun, he said, an ETF “is a great instrument for big game hunting but it is also great for suicide.”

ETFs had lower costs than conventional index funds, so they started to track smaller sectors of the stock market or individual countries. While once it had been too difficult to trade minute by minute out of Brazil, for example, and into India—the transaction costs alone involved in transferring the money would make this prohibitively expensive—it was now possible to do so by selling an ETF of Brazilian stocks and buying one devoted to India. This was great for international hedge fund managers surfing on the sums that investors were giving them. Flows became so great that they overwhelmed local factors, so the BRICs traded in line with the West.

Thus it was that in the early years of BRIC investing, hedge funds found that they could use ETFs for the financial equivalent of highly successful big game hunting. Anyone who bought the MSCI’s BRIC index at rock bottom, just before Lula was elected, and then held it for five years, would have made a staggering 750 percent. Investing in Brazil alone netted 1600 percent.3

As money rolled in, it displaced everything else. There were ways for the market to balance this—an influx should push up the currency, reduce exports, and hence choke off share prices. But it did not work that way. Instead, currencies and stocks, driven by the same investors making the same bet, kept rising. Even Warren Buffett, in 2006, made a big bet on the Brazilian real (which paid off for him).

In the four years from 2005 (a period including the crisis), funds dedicated to the BRIC nations alone grew to have assets of $112 billion and took in $42.2 billion in new money. BRIC-specialist funds accounted for one-third of all funds flowing into emerging markets.

The flows often caused alarm for their recipients. Brazil went in five years from bust to bubble. Daily trading on the Bovespa averaged 2.5 billion reals in 2006. The next year it averaged 4.5 billion reals. And by the end of the year, when the Bovespa itself floated on the market, volume was about 8 billion reals. When it floated, the Bovespa’s valuation implied that it was worth about 50 percent more than the London Stock Exchange. Its most obvious weapon to deal with such overheating—raising interest rates—did not help because it attracted even more foreign money from investors buying the currency as part of a carry trade

These are symptoms of index-led investing—indiscriminate bets on countries and sectors, rather than the on-the-ground detective work that emerging markets investors had once done. But the belief was so strong that the BRICs were a one-way, decoupled bet that they helped to inflate a new “super-bubble” that crossed many asset classes.

The BRICs did deliver in one way. By 2009, O’Neill’s forecasts were on track. China’s economy overtook Germany’s when he said it would. As for their companies, aggregate profits in the BRICs grew at 60 percent per year from 2006 to 2008, until the crash intervened. This was triple the rate of developed countries and double the rate of other emerging countries.4 International investors helped turn the BRICs into a bubble, but there was real and impressive corporate growth.

The biggest problem with the BRIC idea was that it boiled down to a new way to buy natural resources. If the billions of India and China were at last to receive the living standards of people in the west, they would need to gobble up many commodities to do it. From foodstuffs to industrial metals to oil, the BRIC idea suggested that commodity prices were going up. And that opened up more vistas for financial engineering and synchronized markets

In Summary

• BRICs investing spurred money into emerging markets. It also pushed up emerging market currencies and commodity prices.

• Thanks to the way the money was invested, with instruments like ETFs, the flows were driven by sentiment in the developed world, not the facts of the emerging world.