Chapter 15. Commodities

“We’re in a secular bull market in commodities, which started early in 1999.... I went back and looked, and the shortest bull market in commodities I could find lasted 15 years and the longest lasted 23 years. So, if history is any guide, this bull market will last sometime until 2014 and 2022.”

Jim Rogers, Commodities Investor

Index investing in commodities opened a new market to mainstream investors and changed the nature of the commodity markets, prompting them to move in line with stocks. It also helped spur huge rises in oil, metals, and food prices and pushed the dollar down.

In 2004, Gary Gorton, a professor at Yale University’s School of Management, and Geert Rouwenhoorst from Stanford,1 published a working paper. Despite its dense mathematics, it became a cult classic for investment managers and sparked institutions to move huge sums into commodities, in the belief that they were not correlated to stocks. In the process, commodities started moving in alignment with stocks.

Their key finding was that commodity futures could be treated as an asset class, like stocks. Over time, commodities were not correlated with equities or bonds, but averaged almost exactly the same return. Different commodities, like heating oil and coffee, had low correlations with each other. Gorton and Rouwenhoorst found that between 1959 to 2004, buying and holding a basket of commodity futures delivered average annual returns of 11.5 percent: identical to stocks, only with somewhat lower volatility. This sounds dull, but it meant that a pension fund could reduce its risk by adding commodities to stocks. The expected return was the same, but as commodities were uncorrelated, they would often do well while stocks were doing poorly and vice versa.

One study by Ibbotson Associates for PIMCO went further and found that for any given level of risk, adding commodity futures to a portfolio of stocks, bonds, and cash would increase expected returns. For asset managers required to follow the dictates of modern portfolio theory, which required them to look for uncorrelated assets, these were golden words.2

Commodities had long been deep and liquid markets, but they were peopled by producers and their customers. Mainstream investors in stocks and bonds generally steered clear because they lacked detailed knowledge of capacity in each market. Commodity traders knew about piles of copper sitting in warehouses, or the cost of refining oil, or the forecast for the next soybean harvest—factors that did not overlap with stocks and bonds.

The new investors were different. They invested in commodities as an asset class, just as they invested in stocks—passively, through indexes. And so the “financialization” of commodities began: Goldman Sachs and AIG offered indices of futures in different commodities; institutions bought funds linked to them; futures contracts were introduced that were backed by those indices; prices rose; and money piled in.

As with the BRICs, the new interest coincided with a buying opportunity. The oil price bottomed in 1999 at about $12 per barrel. Over the next eight years it rose six-fold, even after inflation was taken into account—equaling the rise from its low in 1973 to the crisis highs in 1980, which inflicted stagflation on the world. From 2007, it doubled again amid the 2008 crisis.

This happened without any of the drastic interruptions to oil supply that hit in the 1970s. And other commodities did even better: Copper rose more than 40 percent in 2005, then rose another 40 percent in 2006. Even soybeans rose more than 80 percent in 2007 alone, sparking food riots across the emerging world. Returns like this attracted a crowd of investors, as commodities became less a superior diversification tool and more about chasing hot performance. Providers of ETFs found a way to let such performance chasers play commodity prices directly. Using futures, banks could underwrite notes that rose or fell in line with commodity prices. These notes would then underpin exchange-traded securities, which proved raucously popular with investors.

Many veteran commodity investors worried both about the influx of new money and about the way it behaved once it hit the market. Commodity futures expire at finite dates. For example, when oil producers want to guarantee a price for April next year, they can sell futures that guarantee the buyer a fixed price the next April. If that buyer is an airline, they now have a handle on their future costs. Speculators’ normal role is to act as go-betweens between producers and suppliers and make money on short-term rises and falls while doing so. The notion of index investors passively buying and holding commodities was a new one for the market. As each futures contract neared its expiration, index funds would sell it and buy into the future for the next month, often making a profit in the process. Behaving this way arguably put upward pressure on prices.

This generated controversy, and in 2008 the U.S. Senate held hearings on the issue. Senator Joseph Lieberman called for limits on index investing. “We may need to limit the opportunity people have to maximize their profits because a lot of the rest of us are paying through the nose, including some who can’t afford it,” he said.3

These arguments rest on the circumstantial evidence that commodity prices rose as money poured into index funds. Detailed academic studies have so far failed to find a causal link between the two. But the influx of new money may well have affected commodities’ low correlation with other assets. Gary Gorton, whose paper on commodities’ low correlations helped fire institutions’ interest, stands by those findings for the long term. “You can argue whatever you want about the last three years, two years, one year, six months. That’s not how we do research,” he told the Financial Times in 2010. But he concedes the possibility that the influx of money had an effect. “There were people who traded in equities and people who traded in commodities and they were different groups. To the extent that they became the same group, there’s a tendency for those correlations to become positive,” he said.4 He pointed to the experience of Mexican companies when they take out a dual listing in the United States to attract U.S. investors—and generally start to correlate more with U.S. markets.

There is another problem, which echoes the objections to the research that attracted Michael Milken to high-yield bonds. Commodities were indeed uncorrelated assets when they were not treated as their own asset class, but there was an issue of capacity. While low-grade bonds or commodities remained areas for specialists who did not touch other markets, they might well outperform other markets and stay uncorrelated with them. Once more money entered and investors with different motivations and behaviors started relying on the old relationships to hold, there was reason to fear that they would not stay uncorrelated.

As the oil price rose, traders found other ways to rationalize the spike. They clung to the theory of “Peak Oil”—the idea that the world’s production of oil has peaked and started a gradual decline. At some point, of course, this theory will come true. Supply rose somewhat in the early years of the oil rally, so Peak Oil does not explain the entire rally. But in 2007, supply slipped, fueling Peak Oil theorists These arguments needed geologists to resolve them, rather than economists, but as oil rose, so the classic bubble psychology took over and many believed falling supply caused the price rises.

Another rationalization came from a much older theory. Nikolai Kondratieff, a Marxist revolutionary executed by Stalin in the 1930s, left behind a theory that commodity prices follow “super-cycles,” each lasting a decade or two. Periods of stagnant commodity prices would be followed by decade-long periods when they rose. This had implications for stocks. Stocks had stagnated when Kondratieff “waves” were pushing commodity prices upward, as in the 1970s and the 1930s. When commodities were stable, as in the 1980s and 1990s, stocks gained.5 So investors latched on to the notion of a “super-cycle” and protected themselves against problems for equities by stockpiling oil and metals.

But commodities’ relationship with stocks did not work the way it was supposed to. History had shown a long-term negative correlation between oil and share prices. In other words, as the oil price goes up, companies’ costs increase and their profits fall, so their share prices should go down. But now, high commodity prices turned into an argument for buying stocks. In particular, the oil and metals markets had a mutually reinforcing relationship with China. In 2006, the extra or marginal Chinese demand for oil accounted for 72 percent of the total growth in oil consumption across the world.6 Such extreme pressure from demand justified rising prices.

With resources companies making up 69 percent of the market value of the BRIC countries (compared to 39 percent globally),7 BRICs and commodities reinforced each other. If Chinese stocks were rising, this was a sign of increasing demand for commodities, so investors should buy them. If commodities were rising, then China was hungry for growth, so buy China. Shanghai’s stock market doubled in 2006 and entered a bubble in 2007. That was taken as a reason to buy oil and metals—even though higher oil prices should be a problem for a big importer like China.

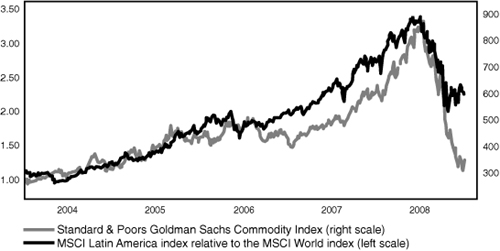

The argument was different for other emerging markets. Russia’s economy is almost wholly dependent on oil. Latin America is rich in metals. But as Figure 15.1 shows, the price of MSCI’s Latin American index, which is dominated by Brazil, came to correlate perfectly with moves in the prices of industrial metals. In effect, Brazil was being priced as though it were one large copper mine—but in fact, it is a more diversified economy than that (and a surprisingly closed one). With exports making up only 14 percent of its GDP, this correlation was plainly taken too far.

Figure 15.1. Commodity prices drive Latin American stocks.

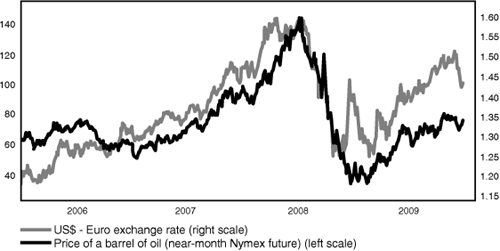

Rising commodity prices also had an impact on currencies. If copper prices rise in dollars, then Brazilian copper miners receive more dollars for every ounce of copper they sell. This flow of money pushes up the Brazilian currency. More significantly, almost all commodity transactions are denominated in dollars. If a dollar is worth less, then commodity prices must rise to reflect this. So worries that the dollar would fall translated into rising commodity prices, rising commodity prices translated into a lower dollar, and traders knowing about this relationship could hedge against a weaker dollar by buying commodities. The correlation between the dollar and the oil price grew absurdly tight (see Figure 15.2).

Figure 15.2. The dollar and oil: in lock-step

Carry traders, of course, took even greater advantage by borrowing cheaply in yen. Currencies backed by resource-rich countries, such as Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa, rose dramatically. The carry trade money could then be recycled into BRIC stocks or into commodities.

The sum effect of all this activity was to push up commodity prices ever further, taking emerging currencies with them. The forces driving currencies, commodities, and emerging markets became indistinguishable and all were ultimately driven by the appetite for risk of traders in the western stock markets. None of this is normal. Commodities, like exchange rates, are supposed to be balancing mechanisms. If demand exceeds supply, prices rise until demand drops again—continued rising prices choke off the economy, as they did in the 1970s. But financializing commodities turned this logic on its head and drove a self-reinforcing synchronized bubble. All it needed to inflate it to a scale that could endanger the entire global economy was an injection of artificially cheap credit—and financial engineers could provide it.

In Summary

• Index investing in commodities as an asset class contributed to a big bull market that also pushed up emerging markets’ stocks and currencies.

• Historical relationships between commodities and stocks were reversed and commodities moved more closely in line with equities.