Chapter 19. Trust

“No, sir, the first thing is character. Before money or anything else. Money cannot buy it. Because a man I do not trust could not get money from me on all the bonds in Christendom.”

J.P. Morgan, when asked in 1913 if money or property was the basis of commercial credit

Financial markets rely on trust. Uncertainty over the location of subprime losses caused a crisis of confidence in the summer of 2007. Central bank intervention averted disaster, as markets still trusted governments and central banks. But this intensified the problem of moral hazard.

“The Fed is asleep!” yelled Jim Cramer, CNBC’s pundit-in-chief. “We have Armageddon. In the fixed-income markets, we have Armageddon.” On August 3, 2007, he descended into a five-minute tirade against the Fed, where the former Princeton University economist Ben Bernanke had replaced Alan Greenspan a year earlier. “Bernanke is being an academic! It is no time to be an academic. He has no idea how bad it is out there. He has no idea! He has no idea!” he screamed on live television. “My people have been in this game for 25 years. And they are losing their jobs and these firms are going to go out of business, and he’s nuts! They’re nuts! They know nothing!”1

As trading room television sets tend to be switched to CNBC, in large part to see Cramer, the rant had an impact. Even though money markets had usurped the roles once played by banks, they were left unheeded most of the time, and it was news to most investors that they were in trouble. Cramer now revealed that the problem for mortgages had infected the price of money itself.

He also waded into the debate over moral hazard. The “Greenspan Put,” with lower interest rates whenever the market got into trouble, had helped markets rise to this point. Some at the Fed wanted to take a stand and force markets to realize that there was no “put” if the market went down. “The punishment has been meted out to those who have done misdeeds and made bad judgments,” said Bill Poole, governor of the St. Louis Fed. “We are getting good evidence that the companies and hedge funds that are being hit are the ones who deserve it.”

Cramer argued that distaste for moral hazard was for “academics” like Poole, whom he called “shameful”. The theories looked good on paper, but in the real world they did not make sense. Too many people could be hurt by a central bank attempt to show them that there were real risks out there. The problem boiled down to a loss of trust that worked its way out in a few dozen dealing rooms across the world and was virtually invisible to anyone on the outside.

The problem boiled down to a loss of trust that worked its way out in a few dozen dealing rooms across the world and was virtually invisible to anyone on the outside. An analogy from Harry Potter illustrates the problem.2 The evil Lord Voldemort, the schoolboy wizard’s great enemy, splits his soul into small pieces and hides them in objects around the world. Until all of them can be found and destroyed, he cannot be killed. In the same way, the process of securitization had left “toxic” subprime assets, many of them worthless, on the books of banks across the world. Nobody knew where they were, and until they were identified, all banks were suspect. Fragments of the soul of Lord Voldemortgage might lurk on any balance sheet. And with that, trust broke down. The collateral offered in return for a loan might prove worthless, so banks simply stopped lending to each other.

This drama played out in the “repo” market, where many banks increasingly chose to finance themselves. In repo transactions, banks borrow just for one night, in return for putting up bonds that they promise to repurchase (or “repo”) the next day. Investment banks relied on such funding, meaning they could run out of money altogether if denied repo funds for only a few days. That seemed a real possibility. Banks would ask for funds, put up securities as collateral, and find no takers unless they agreed to pay ever higher interest rates. The result was that banks were starved of funds.3

Once this basic trust dried up, so did the market for commercial paper—investors were not willing to lend to big companies either, even over short terms. This was particularly true of asset-backed commercial paper with debt as collateral, as all debt securities were now suspect. As large companies often rely on commercial paper to fund their payroll every two weeks, even a brief market interruption could cause disaster.

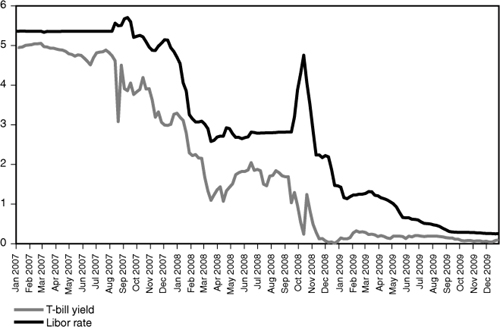

These dull markets are like the plumbing of the financial system. Nobody cares about them until something breaks and causes a flood. Then, suddenly, nothing is more important. Two indicators, or symptoms, revealed the problem to the outside world. One was the yield paid on Treasury bills. These are bonds issued by the U.S. Treasury that will be repaid within three months—the lowest risk investments that exist. When investors lose their faith in other low-risk investments like commercial paper, they tend to move to T-bills. The extra buying pushes down their yields, so a fall in T-bill yields shows that trust is breaking down.

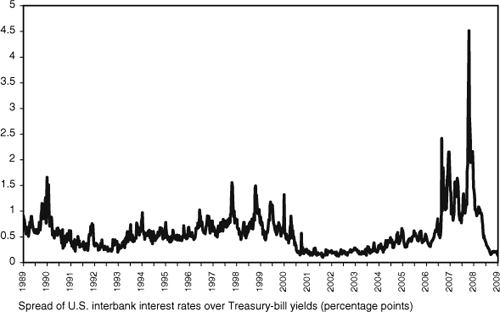

Secondly, there is the gap between the rate at which banks lend to each other (known as LIBOR, short for the London Inter-Bank Offer Rate) and the T-bill rate—a measure known as the TED spread. LIBOR is usually slightly higher, reflecting the slight extra risk that goes with lending to a big bank rather than to the government. The gap between the two tends to be very stable over time, and if it widens, this shows that banks’ trust in each other is breaking down. As Figure 19.1 shows, trust was unnaturally strong during the years of the Great Moderation and broke down completely in the months following August 2007 (see Figure 19.2). Cramer was merely voicing the fears already apparent in money market prices—and throwing down the gauntlet to the Fed.

Figure 19.1. The “TED Spread”—the gauge of trust

Figure 19.2. Breakdown in trust: T-bill yields collapse while bank lending rates soar

The plumbing crisis came to a head in the sleepy last week of August when Countrywide Financial, which originated some 17 percent of all U.S. mortgages, found it hard to sell commercial paper. The market guessed that it was sitting on terrible losses and refused to buy (or in other words, refused to give it a short-term loan). A Countrywide collapse would have caused unthinkable damage to the economy, so throughout the summer, as its crisis deepened, its shares moved in almost perfect alignment with Treasury bills. Any sign that things looked worse for Countrywide sparked a race for T-bills. On the morning of August 16, it failed to raise funds by means of commercial paper. Its shares fell 40 percent in hours, while the yield on the three-month T-bill fell by half a percentage point—an enormous move in this market—as investors fled anything that might have mortgages for collateral.4 This was the worst market seizure since LTCM.

Cooler heads, however, were playing a game of chicken. Named after the scene in James Dean’s Rebel Without a Cause where two young rebels accelerate their cars toward the edge of the cliff, the loser of a chicken game is the one who swerves first. The problem is that the winner might kill himself in the process of winning. Did the Fed have the nerve to let Countrywide go down? By buying stocks, traders bet that the banking system was in such jeopardy that the central bank would have to swerve. The S&P 500 bounced in the last hours of the afternoon and closed higher for the day.

The next morning, the Fed announced that it was cutting the discount rate at which it lends to banks from 6.25 to 5.75 percent (prompting Countrywide stock to rise 60 percent in four hours), and it followed through with another rate cut at its next meeting. Traders rejoiced that the “Greenspan Put” had been replaced by the “Bernanke Put.” In the two months following the nadir of the Countrywide crisis, the S&P 500 rose 14 percent.

How did this happen? Investors were following the script from the LTCM crisis nine years earlier and assuming that the problems were restricted to Countrywide, just as they had been restricted to LTCM a decade earlier. Once more, lower rates from the Fed prompted money to gush to the parts of the economy that were healthiest and least in need of help—which in 1999 had been tech stocks.

The equivalent of tech stocks in 2007 was emerging markets. MSCI’s emerging markets index hit a bottom on August 16 and then went on a ten-week rally. By October 31, Halloween, it had risen 40 percent, while the BRICs rocketed up by 57 percent. Western appetite for risk, more than anything else, drove them upward. In the words of the Prince song, investors were trying to “party like it’s 1999.” The Fed had been challenged and had blinked. In this way, a funding crisis for a Californian mortgage-lender turned into a boon for companies in Brazil, Russia, India, and China. And if anyone thought this was sustainable, they were wrong. World markets were now critically vulnerable to a run on the banks—and the banks were poised for just such a run.

In Summary

• Banking, even when carried out by money markets, relies on trust. Without it, the whole financing system is endangered.

• Cheap rates can bail out money markets, but at the cost of inflating speculative bubbles in sectors that do not need help.