CHAPTER

ONE

OVERVIEW OF THE TYPES AND FEATURES OF FIXED INCOME SECURITIES

FRANK J. FABOZZI, PH.D., CFA, CPA

Professor of Finance

EDHEC Business School

MICHAEL G. FERRI, PH.D.

Professor of Finance

George Mason University

STEVEN V. MANN, PH.D.

Professor of Finance

The Moore School of Business

University of South Carolina

This chapter will explore some of the most important features of bonds, preferred stock, and structured products and provide the reader with a taxonomy of terms and concepts that will be useful in the reading of the specialized chapters to follow.

BONDS

Type of Issuer

One important characteristic of a bond is the nature of its issuer. Although non-U.S. governments and firms raise capital in U.S. financial markets, the three largest issuers of debt are domestic corporations, municipal governments, and the federal government and its agencies. Each class of issuer, however, features additional and significant differences.

Domestic corporations, for example, include regulated utilities as well as less regulated manufacturers. Furthermore, each firm may sell different kinds of bonds: Some debt may be publicly placed, whereas other bonds may be sold directly to one or only a few buyers (referred to as a private placement); some debt is collateralized by specific assets of the company, whereas other debt may be unsecured. Municipal debt is also varied: “General obligation” bonds (GOs) are backed by the full faith, credit, and taxing power of the governmental unit issuing them; “revenue bonds,” on the other hand, have a safety, or creditworthiness, that depends on the vitality and success of the particular entity (such as toll roads, hospitals, or water systems) within the municipal government issuing the bond.

The U.S. Treasury has the most voracious appetite for debt, but the bond market often receives calls from its agencies. Federal government agencies include federally related institutions and government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs).

It is important for the investor to realize that, by law or practice or both, these different borrowers have developed different ways of raising debt capital over the years. As a result, the distinctions among the various types of issuers correspond closely to differences among bonds in yield, denomination, safety of principal, maturity, tax status, and such important provisions as the call privilege, put features, and sinking fund. As we discuss the key features of fixed income securities, we will point out how the characteristics of the bonds vary with the obligor or issuing authority. A more extensive discussion is provided in later chapters in this book that explain the various instruments.

Maturity

A key feature of any bond is its term-to-maturity, the number of years during which the borrower has promised to meet the conditions of the debt (which are contained in the bond’s indenture). A bond’s term-to-maturity is the date on which the debt will cease and the borrower will redeem the issue by paying the face value, or principal. One indication of the importance of the maturity is that the code word or name for every bond contains its maturity (and coupon). Thus the title of the Anheuser Busch Company bond due, or maturing, in 2016 is given as “Anheuser Busch 85/8s of 2016.” In practice, the words maturity, term, and term-to-maturity are used interchangeably to refer to the number of years remaining in the life of a bond. Technically, however, maturity denotes the date the bond will be redeemed, and either term or term-to-maturity denotes the remaining number of years until that date.

A bond’s maturity is crucial for several reasons. First, maturity indicates the expected life of the instrument, or the number of periods during which the holder of the bond can expect to receive the coupon interest and the number of years before the principal will be paid. Second, the yield on a bond depends substantially on its maturity. More specifically, at any given point in time, the yield offered on a long-term bond may be greater than, less than, or equal to the yield offered on a short-term bond. As will be explained in Chapter 8, the effect of maturity on the yield depends on the shape of the yield-curve. Third, the volatility of a bond’s price is closely associated with maturity: Changes in the market level of rates will wrest much larger changes in price from bonds of long maturity than from otherwise similar debt of shorter life.1 Finally, as explained in Chapter 2, there are other risks associated with the maturity of a bond.

When considering a bond’s maturity, the investor should be aware of any provisions that modify, or permit the issuer to modify, the maturity of a bond. Although corporate bonds (referred to as “corporates”) are typically term bonds (issues that have a single maturity), they often contain arrangements by which the issuing firm either can or must retire the debt early, in full or in part. Some corporates, for example, give the issuer a call privilege, which permits the issuing firm to redeem the bond before the scheduled maturity under certain conditions (these conditions are discussed below). Municipal bonds may have the same provision. The U.S. government no longer issues bonds that have a call privilege. The last callable bond was called in November 2009. Many industrials and some utilities have sinking-fund provisions, which mandate that the firm retire a substantial portion of the debt, according to a prearranged schedule, during its life and before the stated maturity. Municipal bonds may be serial bonds or, in essence, bundles of bonds with differing maturities. (Some corporates are of this type, too.)

Usually, the maturity of a corporate bond is between 1 and 30 years. This is not to say that there are not outliers. In fact, financially sound firms have begun to issue longer-term debt in order to lock in long-term attractive financing. For example, in the late 1990s, there were approximately 90 corporate bonds issued with maturities of 100 years.

Although classifying bonds as “short term,” “intermediate term,” and “long term” is not universally accepted, the following classification is typically used. Bonds with a maturity of 1 to 5 years are generally considered short term; bonds with a maturity between 5 and 12 years are viewed as intermediate term (and are often called notes). Long-term bonds are those with a maturity greater than 12 years.

Coupon and Principal

A bond’s coupon is the periodic interest payment made to owners during the life of the bond. The coupon is always cited, along with maturity, in any quotation of a bond’s price. Thus one might hear about the “IBM 6.5 due in 2028” or the “Campbell’s Soup 8.875 due in 2021” in discussions of current bond trading. In these examples, the coupon cited is in fact the coupon rate, that is, the rate of interest that, when multiplied by the principal, par value, or face value of the bond, provides the dollar value of the coupon payment. Typically, but not universally, for bonds issued in the United States, the coupon payment is made in semiannual installments. An important exception is mortgage-backed and asset-backed securities that usually deliver monthly cash-flows. In contrast, for bonds issued in some European bond markets and all bonds issued in the Eurobond market, the coupon payment is made annually. Bonds may be bearer bonds or registered bonds. With bearer bonds, investors clip coupons and send them to the obligor for payment. In the case of registered issues, bond owners receive the payment automatically at the appropriate time. All new bond issues must be registered.

Zero-coupon bonds have been issued by corporations and municipalities since the early 1980s. For example, Barclay’s Bank PLC has a zero-coupon bond outstanding due in August 2036 that was issued on August 15, 2006. Although the U.S. Treasury does not issue zero-coupon debt with a maturity greater than one year, such securities are created by government securities dealers. Merrill Lynch was the first to do this with its creation of Treasury Investment Growth Receipts (TIGRs) in August 1982. The most popular zero-coupon Treasury securities today are those created by government dealer firms under the Treasury’s Separate Trading of Registered Interest and Principal Securities (STRIPS) Program. Just how these securities—commonly referred to as Treasury strips—are created will be explained in Chapter 9. The investor in a zero-coupon security typically receives interest by buying the security at a price below its principal, or maturity value, and holding it to the maturity date. The reason for the issuance of zero-coupon securities is explained in Chapter 9. However, some zeros are issued at par and accrue interest during the bond’s life, with the accrued interest and principal payable at maturity.

Sovereign governments and corporations issue securities with a coupon rate tied to the rate of inflation. These debt instruments, referred to as inflation-linked bonds, or simply “linkers,” have been issued since 1945. The earlier issuers of linkers were the governments of Argentina, Brazil, and Israel. The modern linker is attributed to the U.K. government’s index-linked gilt issued in 1981 followed by Australia, Canada, and Sweden. The United States introduced an inflation-linked security in January 1997, calling those securities Treasury Inflation Protected Securities, or TIPS. These securities, which carry the full faith and credit of the U.S. government, comprised approximately 10% of the outstanding U.S. Treasury market as of mid-2009. Shortly after the introduction of TIPS in 1997, U.S. government-related entities such as the Federal Farm Credit, Federal Home Loan Bank, Fannie Mae, and the Tennessee Valley Authority began issuing linkers.

Different designs can be employed for linkers. The reference rate that is a proxy for the inflation rate is changes in the consumer price index (CPI). In the United Kingdom, for example, the index used is the Retail Prices Index (All Items), or RPI. In France, there are two linkers with two different indexes: the French CPI (excluding tobacco) and the Eurozone’s Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) (excluding tobacco). In the United States, the Consumer Price Index–Urban, Non-Seasonally Adjusted (denoted by CPI-U), is calculated by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.2

There are securities that have a coupon rate that increases over time. These securities are called step-up notes because the coupon rate “steps up” over time. For example, a six-year step-up note might have a coupon rate that is 5% for the first two years, 5.8% for the next two years, and 6% for the last two years. Consider a stairway note issued by Barclays Bank PLC in July 2009. The initial coupon was 2.8% until January 2010 and thereafter the coupon rate reset every six months to the maximum of the previous coupon rate or six-month LIBOR.

In contrast to a coupon rate that is fixed for the bond’s entire life, the term floating-rate security or floater encompasses several different types of securities with one common feature: The coupon rate will vary over the instrument’s life. The coupon rate is reset at designated dates based on the value of some reference rate adjusted for a spread. For example, consider a floating-rate note issued in September 2007 by Bank of America that matured in September 2011. This floater delivered cash flows quarterly and had a coupon formula equal to three-month LIBOR plus 50 points.

Typically, floaters have coupon rates that reset more than once a year (e.g., semiannually, quarterly, or monthly). Conversely, the term adjustable-rate or variable-rate security refers to those issues whose coupon rates reset not more frequently than annually.

There are several features about floaters that deserve mention. First, a floater may have a restriction on the maximum (minimum) coupon rate that will be paid at any reset date called a cap (floor). Second, while the reference rate for most floaters is a benchmark interest rate or an interest rate index, a wide variety of reference rates appear in the coupon formulas. A floater’s coupon could be indexed to movements in foreign exchange-rates, the price of a commodity (e.g., crude oil), movements in an equity index (e.g., the S&P 500), or movements in a bond index (e.g., the Merrill Lynch Corporate Bond Index). Third, while a floater’s coupon rate normally moves in the same direction as the reference rate, there are floaters whose coupon rate moves in the opposite direction from the reference rate. These securities are called inverse floaters or reverse floaters. Consider a hypothetical inverse floater that makes coupon payments according to the following formula:

18% − 2.5 × (three-month LIBOR)

This inverse floater had a floor of 3% and a cap of 15.5%. Finally, range notes are floaters whose coupon rate is equal to the reference rate (adjusted for a spread) as long as the reference rate is within a certain range on the reset date. If the reference rate is outside the range, the coupon rate is zero for that period. For instance, Barclay’s Bank issued a range note in November 2006 (due in November 2016). This issue makes coupon payments quarterly. The investor earns three-month LIBOR + 113 basis points for every day during this quarter that three-month LIBOR is between 0% and 7.5%. Interest accrues at 0% for each day that three-month LIBOR is outside this range. As a result, this range note has a floor of 0%.

Structures in the high-yield (junk bond) sector of the corporate bond market have introduced variations in the way coupon payments are made. For example, in a leveraged buyout or recapitalization financed with high-yield bonds, the heavy interest payment burden the corporation must bear places severe cash-flow constraints on the firm. To reduce this burden, firms involved in leveraged buyouts (LBOs) and recapitalizations have issued deferred-coupon structures that permit the issuer to defer making cash interest payments for a period of three to seven years. There are three types of deferred-coupon structures: (1) deferred-interest bonds, (2) step-up bonds, and (3) payment-in-kind bonds. These structures are described in Chapter 12.

Another high-yield bond structure allows the issuer to reset the coupon rate so that the bond will trade at a predetermined price. The coupon rate may reset annually or reset only once over the life of the bond. Generally, the coupon rate will be the average of rates suggested by two investment banking firms. The new rate will then reflect the level of interest rates at the reset date and the credit-spread the market wants on the issue at the reset date. This structure is called an extendible reset bond. Notice the difference between this bond structure and the floating-rate issue described earlier. With a floating-rate issue, the coupon rate resets based on a fixed spread to some benchmark, where the spread is specified in the indenture and the amount of the spread reflects market conditions at the time the issue is first offered. In contrast, the coupon rate on an extendible reset bond is reset based on market conditions suggested by several investment banking firms at the time of the reset date. Moreover, the new coupon rate reflects the new level of interest rates and the new spread that investors seek.

One reason that debt financing is popular with corporations is that the interest payments are tax-deductible expenses. As a result, the true after-tax cost of debt to a profitable firm is usually much less than the stated coupon interest rate. The level of the coupon on any bond is typically close to the level of yields for issues of its class at the time the bond is first sold to the public. Some bonds are issued initially at a price substantially below par value (called original-issue discount bonds, or OIDs), and their coupon rate is deliberately set below the current market rate. However, firms usually try to set the coupon at a level that will make the market price close to par value. This goal can be accomplished by placing the coupon rate near the prevailing market rate.

To many investors, the coupon is simply the amount of interest they will receive each year. However, the coupon has another major impact on an investor’s experience with a bond. The coupon’s size influences the volatility of the bond’s price: The larger the coupon, the less the price will change in response to a change in market interest rates. Thus the coupon and the maturity have opposite effects on the price volatility of a bond. This will be illustrated in Chapter 7.

The principal, par value, or face value of a bond is the amount to be repaid to the investor either at maturity or at those times when the bond is called or retired according to a repayment schedule or sinking-fund provisions. But the principal plays another role, too: It is the basis on which the coupon or periodic interest rests. The coupon is the product of the principal and the coupon rate.

Participants in the bond market use several measures to describe the potential return from investing in a bond: current yield, yield-to-maturity, yield-to-call for a callable bond, and yield-to-put for a putable bond. A yield-to-worst is often quoted for bonds. This is the lowest yield of the following: yield-to-maturity, yields to all possible call dates, and yields to all put dates. The calculation and limitations of these yield measures are explained and illustrated in Chapter 6.

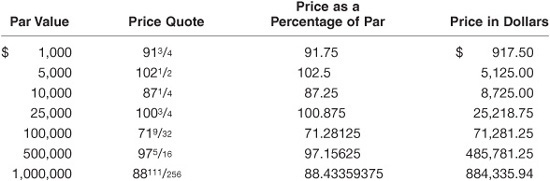

The prices of most bonds are quoted as percentages of par or face value. To convert the price quote into a dollar figure, one simply divides the price by 100 (converting it to decimal) and then multiplies by the par value. The following table illustrates this.

There is a unique way of quoting pricing in the secondary market for Treasury bonds and notes. This convention is explained in Chapter 9.

Call and Refunding Provisions

If a bond’s indenture contains a call feature or call provision, the issuer retains the right to retire the debt, fully or partially, before the scheduled maturity date. The chief benefit of such a feature is that it permits the borrower, should market rates fall, to replace the bond issue with a lower-interest-cost issue. The call feature has added value for corporations and municipalities. It may in the future help them to escape the restrictions that frequently characterize their bonds (about the disposition of assets or collateral). The call feature provides an additional benefit to corporations, which might want to use unexpectedly high levels of cash to retire outstanding bonds or might wish to restructure their balance sheets.

The call provision is detrimental to investors, who run the risk of losing a high-coupon bond when rates begin to decline. When the borrower calls the issue, the investor must find other outlets, which presumably would have lower yields than the bond just withdrawn through the call privilege. Another problem for the investor is that the prospect of a call limits the appreciation in a bond’s price that could be expected when interest rates decline.

Because the call feature benefits the issuer and places the investor at a disadvantage, callable bonds carry higher yields than bonds that cannot be retired before maturity. This difference in yields is likely to grow when investors believe that market rates are about to fall and that the borrower may be tempted to replace a high-coupon debt with a new low-coupon bond. (Such a transaction is called refunding.) However, the higher yield alone is often not sufficient compensation to the investor for granting the call privilege to the issuer. Thus the price at which the bond may be called, termed the call price, is normally higher than the principal or face value of the issue. The difference between call price and principal is the call premium, whose value may be as much as one year’s interest in the first few years of a bond’s life and may decline systematically thereafter.

An important limitation on the borrower’s right to call is the period of call protection, or deferment period, which is a specified number of years in the early life of the bond during which the issuer may not call the debt. Such protection is another concession to the investor, and it comes in two forms. Some bonds are noncallable (often abbreviated NC) for any reason during the deferment period; other bonds are nonrefundable (NF) for that time. The distinction lies in the fact that nonrefundable debt may be called if the funds used to retire the bond issue are obtained from internally generated funds, such as the cash-flow from operations or the sale of property or equipment, or from nondebt funding such as the sale of common stock. Thus, although the terminology is unfortunately confusing, a nonrefundable issue may be refunded under the circumstances just described and, as a result, offers less call protection than a noncallable bond, which cannot be called for any reason except to satisfy sinking-fund requirements, explained later. Beginning in early 1986, a number of corporations issued long-term debt with extended call protection, not refunding protection. A number are noncallable for the issue’s life, such as Dow Chemical Company’s 85/8s due in 2006. The issuer is expressly prohibited from redeeming the issue prior to maturity. These noncallable-for-life issues are referred to as bullet bonds. If a bond does not have any protection against an early call, then it is said to be currently callable.

Since the mid-1990s, an increasing number of public debt issues include a so-called make-whole call provision. Make-whole call provisions have appeared routinely in privately placed issues since the late 1980s. In contrast to the standard call feature that contains a call price fixed by a schedule, a make-whole call price varies inversely with the level of interest rates. A make-whole call price (i.e., redemption amount) is typically the sum of the present values of the remaining coupon payments and principal discounted at a yield on a Treasury security that matches the bond’s remaining maturity plus a spread. For example, on January 22, 2008, an industrial firm issued $300 million in bonds with a make-whole call provision that mature on January 15, 2038. These bonds are redeemable at any time in whole or in part at the issuer’s option. The redemption price is the greater of (1) 100% of the principal amount plus accrued interest or (2) the make-whole redemption amount plus accrued interest. In this case, the make-whole redemption amount is equal to the sum of the present values of the remaining coupon and principal payments discounted at the Adjusted Treasury Rate plus 15 basis points.3 The Adjusted Treasury Rate is the bond-equivalent yield on a U.S. Treasury security having a maturity comparable to the remaining maturity of the bonds to be redeemed. Each holder of the bonds will be notified at least 30 days but not more than 60 days prior to the redemption date. This issue is callable at any time, as are most issues with make-whole call provisions. Note that the make-whole call price increases as interest rates decrease, so if the issuer exercises the make-whole call provision when interest rates have decreased, the bondholder receives a higher call price. Make-whole call provisions thus provide investors with some protection against reinvestment rate risk.

A key question is, When will the firm find it profitable to refund an issue? It is important for investors to understand the process by which a firm decides whether to retire an old bond and issue a new one. A simple and brief example will illustrate that process and introduce the reader to the kinds of calculations a bondholder will make when trying to predict whether a bond will be refunded.

Suppose that a firm’s outstanding debt consists of $300 million par value of a bond with a coupon of 10%, a maturity of 15 years, and a lapsed deferment period. The firm can now issue a bond with a similar maturity for an interest rate of 7.8%. Assume that the issuing expenses and legal fees amount to $2 million. The call price on the existing bond issue is $105 per $100 par value. The firm must pay, adjusted for taxes, the sum of call premium and expenses. To simplify the calculations, assume a 30% tax rate. This sum is then $11,190,000.4 Such a transaction would save the firm a yearly sum of $4,620,000 in interest (which equals the interest of $30 million on the existing bond less the $23.4 million on the new, adjusted for taxes) for the next 15 years.5 The rate of return on a payment of $11,900,000 now in exchange for a savings of $4,620,000 per year for 15 years is about 38%. This rate far exceeds the firm’s after-tax cost of debt (now at 7.8% times 0.7, or 5.46%) and makes the refunding a profitable economic transaction.

In municipal securities, refunding often refers to something different, although the concept is the same. Municipal bonds can be prerefunded prior to maturity (usually on a call date). Here, instead of issuing new bonds to retire the debt, the municipality will issue bonds and use the proceeds to purchase enough risk-free securities to fund all the cash-flows on the existing bond issue. It places these in an irrevocable trust. Thus the municipality still has two issues outstanding, but the old bonds receive a new label—they are “prerefunded.” If Treasury securities are used to prerefund the debt, the cash-flows on the bond are guaranteed by Treasury obligations in the trust. Thus they become AAA rated and trade at higher prices than previously. Municipalities often find this an effective means of lowering their cost of debt.

Sinking-Fund Provision

The sinking-fund provision, which is typical for publicly and privately issued industrial bonds and not uncommon among certain classes of utility debt, requires the obligor to retire a certain amount of the outstanding debt each year. Generally, the retirement occurs in one of two ways. The firm may purchase the amount of bonds to be retired in the open market if their price is below par, or the company may make payments to the trustee who is empowered to monitor the indenture and who will call a certain number of bonds chosen by lottery. In the latter case, the investor would receive the prearranged call price, which is usually par value. The schedule of retirements varies considerably from issue to issue. Some issuers, particularly in the private-placement market, retire most, if not all, of their debt before maturity. In the public market, some companies may retire as little as 20% to 30% of the outstanding par value before maturity. Further, the indenture of many issues includes a deferment period that permits the issuer to wait five years or more before beginning the process of sinking-fund retirements.

There are three advantages of a sinking-fund provision from the investor’s perspective. The sinking-fund requirement ensures an orderly retirement of the debt so that the final payment, at maturity, will not be too large. Second, the provision enhances the liquidity of some debt, especially for smaller issues with thin secondary markets. Third, the prices of bonds with this requirement are presumably more stable because the issuer may become an active participant on the buy side when prices fall. For these reasons, the yields on bonds with sinking-fund provisions tend to be less than those on bonds without them.

The sinking fund, however, can work to the disadvantage of an investor. Suppose that an investor is holding one of the early bonds to be called for a sinking fund. All the time and effort put into analyzing the bond has now been wasted, and the investor will have to choose new instruments for purchase. Also, an investor holding a bond with a high coupon at the time rates begin to fall is still forced to relinquish the issue. For this reason, in times of high interest rates, one might find investors demanding higher yields from bonds with sinking funds than from other debt.

The sinking-fund provision also may harm the investor’s position through the optional acceleration feature, a part of many corporate bond indentures. With this option, the corporation is free to retire more than the amount of debt the sinking fund requires (and often a multiple thereof) and to do it at the call price set for sinking-fund payments. Of course, the firm will exercise this option only if the price of the bond exceeds the sinking-fund price (usually near par), and this happens when rates are relatively low. If, as is typically the case, the sinking-fund provision becomes operative before the lapse of the call-deferment period, the firm can retire much of its debt with the optional acceleration feature and can do so at a price far below that of the call price it would have to pay in the event of refunding. The impact of such activity on the investor’s position is obvious: The firm can redeem at or near par many of the bonds that appear to be protected from call and that have a market value above the face value of the debt.

Put Provisions

A putable bond grants the investor the right to sell the issue back to the issuer at par value on designated dates. The advantage to the investor is that if interest rates rise after the issue date, thereby reducing the value of the bond, the investor can force the issuer to redeem the bond at par. Some issues with put provisions may restrict the amount that the bondholder may put back to the issuer on any one put date. Put options have been included in corporate bonds to deter unfriendly takeovers. Such put provisions are referred to as “poison puts.”

Put options can be classified as hard puts and soft puts. A hard put is one in which the security must be redeemed by the issuer only for cash. In the case of a soft put, the issuer has the option to redeem the security for cash, common stock, another debt instrument, or a combination of the three. Soft puts are found in convertible debt, which we describe next.

Convertible or Exchangeable Debt

A convertible bond is one that can be exchanged for specified amounts of common stock in the issuing firm: The conversion cannot be reversed, and the terms of the conversion are set by the company in the bond’s indenture. The most important terms are conversion ratio and conversion price. The conversion ratio indicates the number of shares of common stock to which the holder of the convertible has a claim. For example, Kaiser Aluminum issued $175 million in convertibles in April 2010 that mature in 2015. These convertibles carry a 4.5% coupon with a conversion ratio of 20.6949 shares for each bond. This translates to a conversion price of $48.32 per share ($1,000 par value divided by the conversion ratio 20.6949) at the time of issuance. The conversion price at issuance is also referred to as the stated conversion price.

The conversion privilege may be permitted for all or only some portion of the bond’s life. The conversion ratio may decline over time. It is always adjusted proportionately for stock splits and stock dividends. Convertible bonds are typically callable by the issuer. This permits the issuer to force conversion of the issue. (Effectively, the issuer calls the bond, and the investor is forced to convert the bond or allow it to be called.) There are some convertible issues that have call protection. This protection can be in one of two forms: Either the issuer is not allowed to redeem the issue before a specified date, or the issuer is not permitted to call the issue until the stock price has increased by a predetermined percentage price above the conversion price at issuance.

An exchangeable bond is an issue that can be exchanged for the common stock of a corporation other than the issuer of the bond. There are a handful of issues that are exchangeable into more than one security. One significant innovation in the convertible bond market was the “Liquid Yield Option Note” (LYON) developed by Merrill Lynch Capital Markets in 1985. A LYON is a zero-coupon, convertible, callable, and putable bond. Techniques for analyzing convertible and exchangeable bonds are described in Chapters 14 and 42.

Medium-Term Notes

Medium-term notes are highly flexible debt instruments that can be easily structured in response to changing market conditions and investor tastes. “Medium term” is a misnomer because these securities have ranged in maturity from nine months to 30 years and longer. Since the latter part of the 1980s, medium-term notes have become an increasingly important financing vehicle for corporations and federal agencies. Typically, medium-term notes are noncallable, unsecured, senior debt securities with fixed-coupon rates that carry an investment-grade credit rating. They generally differ from other bond offerings in their primary distribution process, as will be discussed in Chapter 12. Structured medium-term notes, or simply structured notes, are debt instruments linked to a derivative position and are discussed in Chapter 15. For example, structured notes are usually created with an underlying swap transaction. This “hedging swap” allows the issuer to create securities with interesting risk/return features demanded by bond investors.

Warrants

A warrant is an option a firm issues that permits the owner to buy from the firm a certain number of shares of common stock at a specified price. It is not uncommon for publicly held corporations to issue warrants with new bonds.

A valuable aspect of a warrant is its rather long life: Most warrants are in effect for at least two years from issuance, and some are perpetual.6 Another key feature of the warrant is the exercise price, the price at which the warrant holder can buy stock from the corporation. This price is normally set at about 15% above the market price of common stock at the time the bond, and thus the warrant, is issued. Frequently, the exercise price will rise through time, according to the schedule in the bond’s indenture. Another important characteristic of the warrant is its detachability. Detachable warrants are often actively traded on the American Stock Exchange. Other warrants can be exercised only by the bondholder, and these are called nondetachable warrants. The chief benefit to the investor is the financial leverage the warrant provides.

PREFERRED STOCK

Preferred stock is a class of stock, not a debt instrument, but it shares characteristics of both common stock and debt. Like the holder of common stock, the preferred stockholder is entitled to dividends. Unlike those on common stock, however, preferred stock dividends are a specified percentage of par or face value.7 The percentage is called the dividend rate; it need not be fixed but may float over the life of the issue.

Failure to make preferred stock dividend payments cannot force the issuer into bankruptcy. Should the issuer not make the preferred stock dividend payment, usually paid quarterly, one of two things can happen, depending on the terms of the issue. First, the dividend payment can accrue until it is fully paid. Preferred stock with this feature is called cumulative preferred stock. Second, if a dividend payment is missed and the security holder must forgo the payment, the preferred stock is said to be noncumulative preferred stock. Failure to make dividend payments may result in imposition of certain restrictions on management. For example, if dividend payments are in arrears, preferred stockholders might be granted voting rights.

Unlike debt, payments made to preferred stockholders are treated as a distribution of earnings. This means that they are not tax deductible to the corporation under the current tax code. (Interest payments, on the other hand, are tax deductible.) Although the after-tax cost of funds is higher if a corporation issues preferred stock rather than borrowing, there is a factor that reduces the cost differential: A provision in the tax code exempts 70% of qualified dividends from federal income taxation if the recipient is a qualified corporation. For example, if Corporation A owns the preferred stock of Corporation B, for each $100 of dividends received by A, only $30 will be taxed at A’s marginal tax rate. The purpose of this provision is to mitigate the effect of double taxation of corporate earnings. There are two implications of this tax treatment of preferred stock dividends. First, the major buyers of preferred stock are corporations seeking tax-advantaged investments. Second, the cost of preferred stock issuance is lower than it would be in the absence of the tax provision because the tax benefits are passed through to the issuer by the willingness of buyers to accept a lower dividend rate.

Preferred stock has some important similarities with debt, particularly in the case of cumulative preferred stock: (1) The payments to preferred stockholders promised by the issuer are fixed, and (2) preferred stockholders have priority over common stockholders with respect to dividend payments and distribution of assets in the case of bankruptcy. (The position of noncumulative preferred stock is considerably weaker than cumulative preferred stock.) It is because of this second feature that preferred stock is called a senior security. It is senior to common stock. On a balance sheet, preferred stock is classified as equity.

Preferred stock may be issued without a maturity date. This is called perpetual preferred stock. Almost all preferred stock has a sinking-fund provision, and some preferred stock is convertible into common stock. A trademark product of Morgan Stanley is the Preferred Equity Redemption Cumulative Stock (PERCS). This is a preferred stock with a mandatory conversion at maturity.

RESIDENTIAL MORTGAGE-BACKED SECURITIES

A residential mortgage-backed security (RMBS) is an instrument whose cash-flow depends on the cash-flows of an underlying pool of mortgages. In the U.S. market, RMBS are classified into two groups: agency RMBS and nonagency RMBS.

An agency RMBS, the subject of Chapter 25, is one issued by the Government National Mortgage Association (“Ginnie Mae”), the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (“Freddie Mac”), or the Federal National Mortgage Association (“Fannie Mae”). Ginnie Mae is a federal government agency within the Department of Housing and Urban Development. The RMBS issued by this entity is guaranteed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government. Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae are government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs). In September 2008, these two entities were placed into conservatorship run by the Federal Housing Finance Agency. The agency RMBS market is the largest sector of the U.S. bond market as of year-end 2010. In bond indexes such as the Barclays Capital U.S. Aggregate Bond Index, this sector is referred to as simply “mortgage-backed securities” or the “MBS” sector despite the fact that there are also nonagency RMBS.

Nonagency RMBS, the subject of Chapter 31, are issued by thrifts, commercial banks, or private conduits that are not backed by any government entity. These securities are structured so as to provide credit enhancement that support the credit ratings that they receive. At one time, the nonagency RMBS market was divided into two sectors: prime RMBS and subprime RMBS. The classification depended on the credit quality of the pool of borrowers and the type of lien on the properties that were mortgaged. The primary attribute used to categorize the borrower’s credit quality has long been the borrower’s Fair Isaacs or FICO credit score or any one of other related measures that are not discussed here (e.g., an income ratio indicating the borrower’s ability to pay and the loan-to-value ratio measuring the borrower’s equity in the property). Prime borrowers are generally those with FICO scores of 660 or higher. Subprime borrowers are those with impaired credit ratings, typically with FICO scores below 660. However, because of the difficulties faced in the RMBS subprime market that started in the summer of 2007, and the poor performance of the collateral underlying both prime and subprime RMBS, investors no longer draw a sharp distinction between these two sectors of the nonagency RMBS market. Further, few experts believe that the subprime RMBS market will be revived in the future.

RMBS can take three forms: (1) mortgage pass-through securities, (2) collateralized mortgage obligations (CMOs), and (3) stripped mortgage-backed securities. Agency RMBS come in all three forms. Typically nonagency RMBS come only in the second form and, as a result, this sector of the market is referred to as the nonagency CMO market.

Agency RMBS expose an investor to prepayment risk. This is the risk that the borrowers in a mortgage pool will prepay their loans when interest rates decline. Prepayment risk is effectively the same as call risk faced by an investor in a callable corporate or municipal bond. Nonagency RMBS expose investors to both prepayment risk and credit risk, although the major concern by investors in this space is credit risk.

COMMERCIAL MORTGAGE-BACKED SECURITIES

Commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBSs) are backed by a pool of commercial mortgage loans on income-producing property—multifamily properties (i.e., apartment buildings), office buildings, industrial properties (including warehouses), shopping centers, hotels, and health care facilities (i.e., senior housing care facilities). The basic building block of the CMBS transaction is a commercial loan that was originated either to finance a commercial purchase or to refinance a prior mortgage obligation. There are two major types of CMBS deal structures that have been of interest to bond investors, multiproperty single borrowers, and multiproperty conduits. The fastest-growing segment of the CMBS is conduit-originated transactions. Conduits are commercial-lending entities that are established for the sole purpose of generating collateral to securitize.

Unlike residential mortgage loans, where the lender relies on the ability of the borrower to repay and has recourse to the borrower if the payment terms are not satisfied, commercial mortgage loans are nonrecourse loans. This means that the lender can only look to the income-producing property backing the loan for interest and principal repayment. If there is a default, the lender looks to the proceeds from the sale of the property for repayment and has no recourse to the borrower for any unpaid balance. Basically, this means that the lender must view each property as a stand-alone business and evaluate each property using measures that have been found useful in assessing credit risk.

ASSET-BACKED SECURITIES

Asset-backed securities are securities collateralized by assets that are not mortgage loans. In structuring an asset-backed security, issuers have drawn from the structures used in the mortgage-backed securities market. Asset-backed securities have been structured as pass-throughs and as structures with multiple bond classes called pay-throughs, which are similar to CMOs. Credit enhancement is provided by letters of credit, over-collateralization, or senior/subordination.

Three common types of asset-backed securities are those backed by credit card receivables, home equity loans, and automobile loans. Chapters 33 and 34 cover these securities. There are also asset-backed securities supported by a pool of manufactured homes, Small Business Administration (SBA) loans, student loans, boat loans, equipment leases, recreational vehicle loans, senior bank loans, and possibly, the future royalties of your favorite entertainer.

COVERED BONDS

In the wake of the financial crisis of 2008–2009, a bond structure very familiar to European investors—covered bonds—was touted as an alternative funding source for residential mortgage loans. Collateral in the typical European covered bond includes residential/commercial mortgages and public sector debt.

A covered bond is a debt instrument secured by a specific pool of collateralizing assets. Covered bonds, the subject of Chapter 22, differ from the typical mortgage-backed security issued in the United States on a number of dimensions. First, the cover pool remains on the issuer’s balance sheet rather than being sold to a special-purpose entity. Second, the mortgages in the cover pool serve only as collateral for investors, whereas the covered bond’s principal and interest are serviced by the issuer’s cash-flows. Third, mortgage-backed securities are claims to static pools, whereas the cover pool is dynamic, and nonperforming mortgages must be replaced with performing ones. Fourth, unlike MBS, covered bonds are structured to prevent prepayments before maturity. Finally, investors in covered bonds retain an unsecured claim on the issuer for any shortfall due to them (i.e., unpaid principal and interest).

KEY POINTS

• Bonds differ on a number of dimensions, which include type of issuer, maturity, coupon, principal amount, method of redemption, and embedded options.

• Embedded options in a debt instrument are call and refunding provisions, prepayment provisions, optional accelerated provision, put provision, and conversion provision.

• Medium-term notes are highly flexible debt instruments that can be easily structured in response to changing market conditions and investor tastes.

• Structured notes are debt instruments that are linked to a derivative position and allow an issuer to create a customized debt instrument for an investor.

• Preferred stock is a security that shares characteristics of debt and equity.

• Residential RMBS are classified into agency and nonagency securities.

• There are three types of RMBS: (1) pass-throughs, (2) collateralized mortgage obligations, and (3) stripped mortgage-backed securities. Nonagency RMBS typically have the CMO structure.

• Asset-backed securities are collateralized by financial assets other than residential mortgages.

• A covered bond is a debt instrument secured by a specific pool of collateral called a collateral pool.