10

Vlogs, Video Publishing, and Informal Language Learning

TATIANA CODREANU AND CHRISTELLE COMBE

Introduction

Since the late 1990, universities have followed new economic models based on new opportunities offered by the internet in terms of resources and new methods of delivery, in developing blended courses. Online learning and teaching language training modules have been incorporated alongside face‐to‐face education, and research has documented the potential of the webcam for language instruction (Develotte et al. 2010). Moreover, research that has focused on blogs and language learning (Seitzinger 2006) has documented teaching and learning experiences.

However, little has been published so far on vlogs and language learning. Their essential interest lies in the variety and the spontaneity of topics. A 2016 YouTube™ study commissioned by Google shows that millennials exhibit binge‐watching behavior and prefer YouTube as their video destination, and that 79% of them prefer videos created by individuals versus videos created by companies. In a 2018 study, the Pew Research Center confirmed a shift in young people's social media use, with YouTube being the favorite platform for 85% participants (Anderson and Jiang 2018). Waxworks of vloggers such as Zoella and Alfie have been displayed at Madame Tussauds in London since 2015, arguably representing the popularity of vloggers in modern‐day society.

This chapter focuses on informal language learning from YouTube videos that elicits substantial response from those videos' audience in the form of written comments. Our analysis addresses issues in informal language learning and evaluates the potential and limitations of informal language learning in a vlogging context. As Barton and Lee (2013) point out, vlogging's multimodal affordances allow language learners to practice speaking, writing, and listening, and vlogging is particularly suited to autonomous and informal learning. In this chapter, we will first present a current review of literature in the field of vlogging and more specifically in the field of informal language learning. Then, we will highlight the potential and limits of informal learning in the context of vlogs. And finally, we will attempt to discuss vlogs' use in informal language learning and the unique contexts in which language learners are practicing their language ability, while also developing their digital literacy skills and creativity.

Informal language learning and the internet

In this section we will present our methodological approach and the theoretical framework in which our work fits. We will specify what we mean by informal language learning and then will present the impact of Web 2.0 and mobile learning on language learning. Then we will discuss the web‐action oriented and interactional skills in the context of multimodal and multimedia skills and new literacies.

Informal language learning

The concept of informal learning is linked to the circumstances in which it occurs. Previous research focusing on informal language learning investigated different definitions of this concept (Cross 2006; Marsick and Watkins 1990; Rogers 2004).

Cross has defined informal learning as “the unofficial, unscheduled, impromptu way people learn to do their jobs” (p. 19). Building on Cross's concept of informal learning, Toffoli and Sockett (2010a, 2010b) have suggested its adaptability to informal language learning as it

involves practices which do not take place as part of a lesson, whether during class time or as a homework assignment, and any activity prescribed by a teacher in such a context could not therefore be considered an informal learning activity even if the activity itself were indistinguishable from other activities spontaneously engaged in by the language learner.

(2010a, p. 126)

In addition, learners are not necessarily aware of their informal learning. These elements are consistent with existing definitions of informal learning, notably that of Tissot (2004), who considers that learning results from daily activities related to work, leisure, and family, emphasizing that these activities may not be recognized by individuals themselves as participants in their learning. Such a definition differs from that of Cross (2006), who sees informal learning as an intentional activity aimed at developing certain professional skills through networking activities.

Moreover, validation of nonformal and informal programs and activities that promote the acquisition of knowledge and skills has been at the center of UNESCO's Global Citizenship Education (GCED) and Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) since 2016: “Informal learning is never organized, is non‐institutional, and has no established objective in terms of learning outcome – it is also not directed by the learner” (Lockhart 2016, p. 10). The OECD (2016) defines informal learning as “learning by experience” or just experience. The individual's existence predicates exposure to learning situations throughout spaces in society that they travel through and occupy, such as work and home, community activities, and leisure time. This definition is argued to meet majority consensus. Nonformal and informal learning have been investigated by the European Commission in its Education Development Guidelines for 2014–2020 for youth skills for the twenty‐first century, which validate nonformal learning's distinction from informal learning and set recommendations on the recognition of nonformal and informal learning for the Member States. The EU recommendation stipulates that a measure for the recognition of non‐formal and informal learning must be introduced no later than 2018 as the acquired knowledge can increase the competitiveness of young people in the labor market (Council of Europe 2018).

The social web

Transition from Web 1.0 (1993) to Web 2.0 (1999) opened the era of informal learning characterized by users transitioning from being content consumers to content creators. The passage to Web 2.0 was described by Flew (2005) as a change from personal website to blogs. User‐generated content became the new norm with the social web in 2005, and has remained so. YouTube was launched in 2005, allowing users to create videos and vlogs (video blogs which can be described as personal videos posted regularly by users on a specific theme). Moreover, in the context of a multilingual internet, YouTube offers significant potential for learning foreign languages.

The framework of computer‐assisted language learning (CALL) focused initially on language learning and pedagogical implications in terms of skills in different areas such as grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation, and reading (Stockwell 2007). Jarvis and Achilleos (2013) used the MALU structure (mobile‐assisted language use) while questioning the adequacy of the CALL framework to study informal anywhere/anytime language‐learning possibilities introduced by the increase of mobile platforms and the decrease in the use of desktops. However, Derakhshan and Khodabakhshzadeh (2011) suggested an overlap in the meaning of different terminologies used in CALL and mobile learning in terms of collaboration and networking. Stockwell and Hubbard (2013) define MALL as the intersection of CALL and m‐learning (mobile learning) and previous research focused on user perspectives (Alrasheedi and Capretz 2013) and learning outcomes (Burston 2015).

As Son (2018) highlights:

Both pedagogical aspects of mobile learning and personalised learning and technological aspects of mobile devices (cf. massive open online courses (MOOC)) have generated significant interest among CALL researchers and practitioners.

(p. 4)

Son further draws special attention to rapid changes in technology which widen the dimension of CALL. Similarly, Bezemer and Kress (2015) maintain that learning occurs everywhere and highlighted “the social as the frame, as the shaping presence and force for all actors and all action” (p.2).

Learners should develop their multimodal skills, “so that they may benefit from the multimodality of the environment and maximise their learning possibilities” (Guichon and Cohen 2016, p. 14). While the first generation of the web required the user to have technical knowledge in order to publish on the web, the generalization of the concept of the social web (or Web 2.0) allows everyone to create and publish their own online content and thus users are active contributors (Millerand et al. 2010). Moreover, Flichy (2010) points to the web as a realm of amateurs and a democratizer of skills. Thanks to computers and the internet, new amateurs have acquired the knowledge and know‐how that allows them to compete with experts and develop counterexpertise. Flichy compares this movement to political democracy. Flichy argues that web platforms are places of sharing different interests and worlds. This argument is similar to the concept of the pro–am revolution put forward by Leadbeater and Miller (2004). According to them, amateurs broadcast and broaden the knowledge, skills and expertise essential to their practice and identity. Barton and Lee (2013) consider the main characteristics of the social web to be social networking, the principles of collaboration between a community of users, the ability to interact in writing but also to upload videos and photos that other users can comment on, and the investigability of content and sharing.

In the age of Web 2.0 tools and globalization, learners must have particular skills such as the ability to interact in one or more languages (Guerin et al. 2010) while acquiring intercultural skills. They must also learn to develop specific lifelong learning skills, to be connected and use social networks intelligently, to manage different learning contexts (formal, nonformal and informal), to distinguish the relevance of online resources, and to develop a creative mindset. Hauck (2010) also emphasizes the necessity of developing multimodal skills building on concepts put forward by Kress (2003). According to Kress (2003), the Learner 2.0 builds skills expressing ideas through different modes: words, still or moving images, or 3D models. Moreover, Web 2.0 technologies and mobile devices connect people around the world instantly without the restrictions of time and place that normally dictate language instruction and practice. As Barton and Lee (2013) point out:

Communicational changes, with a shift from writing to image as the dominant mode, altering the logic of our communicative practices; and changing technological affordances, with a shift in media from page to screen […]. As we can see, it is this combination of changes in different areas of life that contribute to changes to our communicative practices and landscape.

(p. 2)

Multimodal multimedia competencies and new literacies

The multimodal paradigm was developed by Jewitt and Kress (2003) and Kress (2003). The main modes are: written language, spoken language, visual, audio, tactile, gestural, spatial (Kress 2003); multimodality is defined by Jewitt and et al. (2016) as:

Meaning is made with different semiotic resources, each offering distinct potentialities and limitations. Meaning making involves the production of multimodal wholes. If we want to study meaning, we need to attend to all semiotic resources being used to make a complete whole.

(p. 3)

Initially, traditional literacy was based on a monolithic, monomodal, unilingual, and decontextualized conception. The idea of multiliteracy (New London Group 1996) refers to plurality and diversity modes (the visual, the oral, the written word), languages (plurilingualism), practices, situations, contexts, and technologies. In the current digital environment, media literacy refers to “the set of skills characterizing the individual capable of evolving critically, creatively, autonomously and socialized in the contemporary media environment” (Lebrun et al. 2012, p. 47). Multimodal media literacy is defined by Lacelle and et al. (2018) as follows:

The ability of a person to properly mobilize, in synchronous or asynchronous communication contexts, the most appropriate modal and multimodal semiotics resources and skills for the situation and the medium of the communication.

(p. 8)

Finally, as we write this paper, the definition of digital literacy is not yet fully stabilized. Hoechsmann and De Waard (2015) define digital literacy as follows:

Digital literacy is not a technical category that describes a minimal functional level of technological skills, but rather a broad capacity to participate in a society that uses technology. digital communications in workplaces, government, education, culture, civic spaces, homes and recreation.

(p. 5)

In this new world, a multitude of applications of the social web, constantly renewed, is offered to the user, according to affordances (Barton and Lee 2013; Jones and Hafner 2012; Kress 2004) of space within which it evolves:

These technologies provide new and distinct writing spaces. People explore the affordances of these writing spaces and literate forms are being renegotiated. There is an explosion of new genres and proto‐genres, which are the beginnings of future genres.

(Barton and Lee 2013, p. 16)

For the purposes of the present chapter, we will highlight that the social web has allowed predrawn discursive spaces that generate genres that are interactive and multimodal: written discourse is not only answered by written words, but also by icons and imagery, audio, and video; the opposite also applies.

Studying informal language‐learning vlogs

Our approach to fieldwork consists of observing informal online practices from native digital discourses (Paveau 2017). Fieldwork, as defined by Wolcott (1995), is a form of inquiry that requires a researcher to be immersed in the social activities of individuals. Our research is descriptive and exploratory. Digital data has the distinction of being numerous and labile (Develotte 2012). Harvesting “native digital discourses” (Paveau 2017) means extracting them from their digital environment and denaturing them, so we have not collected any corpus but the examples we will present will serve our arguments and illustrate our point. The researcher may consider that public channels can be used freely in a context of research in the human sciences as long as the research is ethical and is done without commercial use and without consequences for the people mentioned. We therefore choose not to anonymize the data in order to conserve the ecology of the environment. This approach is exploratory in order to open tracks from ethnographic observations of the web for subsequent research that would then deserve to be pursued on a larger scale with participants by questionnaires. We aim to observe how individuals using vlogging practice a foreign language and the contributions and limitations that one observes of such a practice and ongoing social activities of YouTube users. Our techno‐semio‐discursive analysis (Celik and Develotte 2011) approach is descriptive and we try to highlight the discursive behavior of vlog users engaged in multimodal communication contexts.

Vlogging on YouTube

In this section we will present a brief history of vlogs, and more precisely, in the context of language learning before categorizing the different types of vlogs for informal language learning. We focus our study on examples taken on the YouTube platform, which is intrinsically linked to the notion of vlogging seen as the first genuinely popular platform of user‐created video (Burgess and Green 2018).

A brief history of vlogs

Accounts of vlogs can be traced back to 2000, when a blogger, Adam Kontras, posted a long video alongside his blog entry, coining the term vlog. However, vlogging saw an increase in popularity in 2004 with a broadcaster, Andrew Baron, who started to produce daily videos of his show, Rocketboom. On YouTube, vlogs started to be published with a turning point in 2006, when a teenage user, Bree, attracted a large audience on her vlog titled LonelyGirl15. She shared details of her personal life in daily videos.

As video recording equipment evolved, content creators started carrying portable equipment and filming their daily experiences. Over the next years, smartphones allowed a new freedom for vloggers, as they could use the embedded technology to capture new content beyond their desktop and houses. Lien (2012) highlights the attractiveness of vlogs for the vloggers and their audience in terms of perceived value: Seeing their viewers and subscribers as their social capital, vloggers tend to perform playful identities in order to attract more viewers and subscribers.

Videos on YouTube can be public, unlistedvlogs integrate video, text, image, and metadata. or private, open to comments or not. Finally, video bloggers (that is, those who regularly post videos) can also create a channel that other viewers can subscribe to in order to be kept informed of new videos posted. YouTube is perceived by users more as a social network than a video‐sharing site (Barton and Lee 2013; Burgess and Green 2018) because of the special relationship between those posting videos and those viewing and commenting them. “YouTube is based on the visual and includes a great deal of interaction with strangers” (Barton and Lee 2013, p. 40). As Barton and Lee point out, vlogs' multimodal affordances allow language learners to practice speaking, writing, and listening, and they are particularly suited to autonomous and informal learning, because YouTube enables peer learning in a stress‐free environment. YouTube is an important platform for discussions of language learning as it allows learners to innovate and express their individual creativity. Jee (2011) provides an account of mobile Web 2.0 technologies and language learning:

In foreign language classes, learners, as a team, can create a short movie or make a video clip to practice conversation and upload their recordings. After watching other teams' videos, they can give and receive feedback. It does not require any expensive and heavy equipment to create a video clip and the blog is easy to manage.

(p. 166)

Our research focuses in particular on the genre of vlogs (Celik 2014), that is, a web‐based genre that corresponds to a semio‐discursive text produced within the digital environment of YouTube as illustrated by the screenshot of Michael, an American student who is learning French (see in Figure 10.1; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9A54ESetlYQ). A vlog is a complex set composed of different techno‐semio‐discursive elements that should be distinguished. A YouTube account is automatically associated with a Google account. It is then very easy for new vloggers to create their YouTube channel. On YouTube, vloggers are exposed to a discursive space: the home page of their channels is composed of a number of pages and functionalities provided by YouTube. We will not go into all the details of managing and creating a YouTube channel, but we will emphasize the complexity of the task when all the affordances are exploited. Our discussion will focus on uploading a video and its creation. When vloggers want to upload a video, they are faced with two possibilities: uploading a previously recorded video or broadcasting live content. They will then have to fill in a title, a description, and tags. If the video is open to comments, they will also be able to respond to community members who will be forming around the video. Personal vlogs integrate video, text, image, and metadata.

YouTube has created an online course sanctioned by an exam for personal vlogs, called “Vlog Like a Pro.” Barton and Lee (2013) point out new ways of being a creative, active content user. The vlogs on the YouTube channel (txtfrancais; https://www.youtube.com/user/texfrancais) of Michael, the American student who is learning French (see Figure 10.1), demonstrate the different elements we expect from a vlog:

- A video that corresponds to the vlogger's monologue.

- The title of the video, “Je réponds à vos questions” (“I answer your questions”).

- The avatar of the vlogger and the title of his channel (texfrancais).

- A “call to action” to subscribe and the number of subscribers.

- The number of times the video has been viewed (2531 at the date October 2018).

- Actions (add to, share, report, transcription, statistics).

- Graphical buttons enabling the user to indicate “I like this” or “I do not like this.” As of October 2018, 275 had indicated their approval of the video and 0 had indicated their disapproval.

- A personalized introduction by the vlogger in which he wrote a short text and indicated any other channels and social networks.

- YouTube's viewers of the vlog and their comments.

Figure 10.1 Techno‐semio‐discursive space of a vlogger on YouTube. Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9A54ESetlYQ.

Barton and Lee (2013) point out the importance of YouTube's comments space:

Although primarily a video‐based site, YouTube is rich in writing spaces. In addition to sub‐titles and annotations, which can be easily added to the video screen using YouTube's built in video editor, commenting is the key interactive writing space on the site.

(p. 39)

Vlogging and language learning

We will present the state of the art of literature in the field of vlogging and more specifically in the field of informal language learning. Hung (2011) highlighted students' positive perceptions on vlogs for language learning and the pedagogical implication of organizing, reflecting and archiving students' vlogs, seen as products of their work. Jee (2011) points out vlogging practices in foreign language classes for learners to create collaboratively a video clip allowing conversation practice, receiving peer feedback.

Moreover, research draws attention to: YouTube and language learning stimulating learners' autonomy (Watkins and Wilkins 2011); vlogging benefits for both vloggers learning a language and their audience (Ducate et al. 2012); speaking through sharing personal experience (Cong‐Lem 2018); challenges and opportunities of vlogs linked to oral presentations and oral monologues as global trends (Barrett and Liu 2016; Bozkurt and Ataizi 2015), social communication aspects linked to vlogs and intercultural competences (Codreanu and Combe 2018; Santamaria‐Garcia 2018); and the impact of vlogging on improving language proficiency (Maldin et al. 2017; Maulidah 2017). Research on digital discourse has also brought to light vlogs as a genre (Celik 2014) and the need to address multimodal digital skills of learners in a globalized world (Codreanu and Combe 2018).

The potential of informal language learning in the context of vlogs

In this section we will attempt to identify the different modes of informal language learning in the context of vlogs. We would like to highlight different categories of languages and how learners practice their language skills, while also developing their digital literacy skills and creativity. In fact, we will focus on the question of skills in informal learning contexts which are wider than the notion of language learning. Multimodal communication in a globalized world and on the internet is a reflection of these skills. In a previous study (Celik 2014) we emphasized the following categories of vlogs: tutorials, humoristic, lifestyle, personal life, makeup, video games, and learning a language and the importance of the desire to share with a community. We also drew attention to the different types of shots that were used by vloggers: fixed camera, mobile camera, and screen filming.

A continuous monologue within a virtual dematerialized global agora

Vlogging allows the language learner to develop skills of sustained monologues. A vlog in a foreign language requires a regular speaking production in order to retain the audience and the usage of a camera. This competence is difficult to implement as a situation of authentic communication within a classroom setting. Oral presentations in a classroom setting are often reserved for academic purposes and are a somewhat artificial activity (i.e. not spontaneous). Learners are speaking on a subject that has often been recommended to them, in front of a public inclined to judge them, and the presentation is then evaluated by the teacher. This activity is also rare and difficult to implement due to time constraints (many students and little time allocated to this particular task). A vlog's environment allows learners to have a forum to express themselves by choosing the topics. In the example, again of Michael's vlog (see Figure 10.2), we observe that he will speak about his “embarrassing French mistakes” as well as his vision of the “perfect woman” and his reaction to the terrorist attacks of November 2015 that took place in Paris. On the internet, the audience is certainly public and potentially much larger than a continuous monologue in a classroom setting. Whether we think of the classroom or the student auditorium, the fact that the vlogger is alone in front of the camera in a place he has chosen (in his room, his car, outside) and speaking on a subject that he wants to share can give him the impression of practicing the language in a more uninhibited way in a possibly stress‐free environment. It may also facilitate self‐expression. Regularity in the publication of vlogs can be encouraged by the audience's comments.

One of the main characteristics of vlogs is a certain regularity in the publication, regularity that allows a vlogger to retain an audience and share content. Different tools, such as the number of times the video has been viewed, statistical tools, as well as the number of comments, bring to light the audience, the reception of the video. These are all sources encouraging further publication. The number of “I like this” (symbolized by the thumb‐up icon) or “I do not like this” (symbolized by the thumb‐down icon) are also a form of informal peer review.

Figure 10.2 A sustained monologue, fixed camera in the car, centered framing. Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6RtaHAW_GaQ.

Michael's videos are generally popular amongst his audience, who explicitly encourage him to continue his activity. We observe, within the comments, many positive socioaffective marks; among the comments of the videos of the corpus, many are face flattering acts, of which below are some examples. The vlogger can create a small community with which to interact without necessarily having mass media scale, as in these examples:

Tu parle mieux français que moi anglais ! (You speak better French than I speak English)

j'aime trooop son accent j'aimerais tellement parler l'anglais et le coréen courament (I love his accent so much. I would kill to speak English and Korean fluently)

Je suis très contente que tu as une nouvelle vidéo! Ça fait longtemps que je te regarde :) (I am very happy that you have a new video! I've been watching you for a while :))

Your accent is cute, c'est mignon! ^^

Ton française est vraiment bon! (Your French is really good!)

Exclamation marks, redundant punctuation, sometimes repeated “heart” emoticons, adverbs and positive adjectives and comparisons are all marks of the emotional hyperbole found in these comments. A single comment has a slight mockery, which could be perceived as a face threatening act.

Multimodal and multilingual interactions

Given the structure of a vlog, an initial message by video is uploaded on YouTube, followed by comments. According to Paveau's typology (Paveau 2017), these comments can be relational, from the simple “I like” or “I do not like” to the “thank you” comments, or from the discursive conversational type (prolonging the initial message or answering it), metadiscursive (about the video format for example), or even trolling.

Vloggers most often seek not only to retain their audience by asking them to subscribe, but also to generate comments. They may therefore ask a question, a question addressed orally to users and to which they respond by writing comments or by posting another video. Thus, in the video, “My embarrassing French mistakes,” the vlogger asks, “Which language would you like to learn?” and several users respond to it. These comments themselves can also elicit responses and sometimes lengthy engaging discussions.

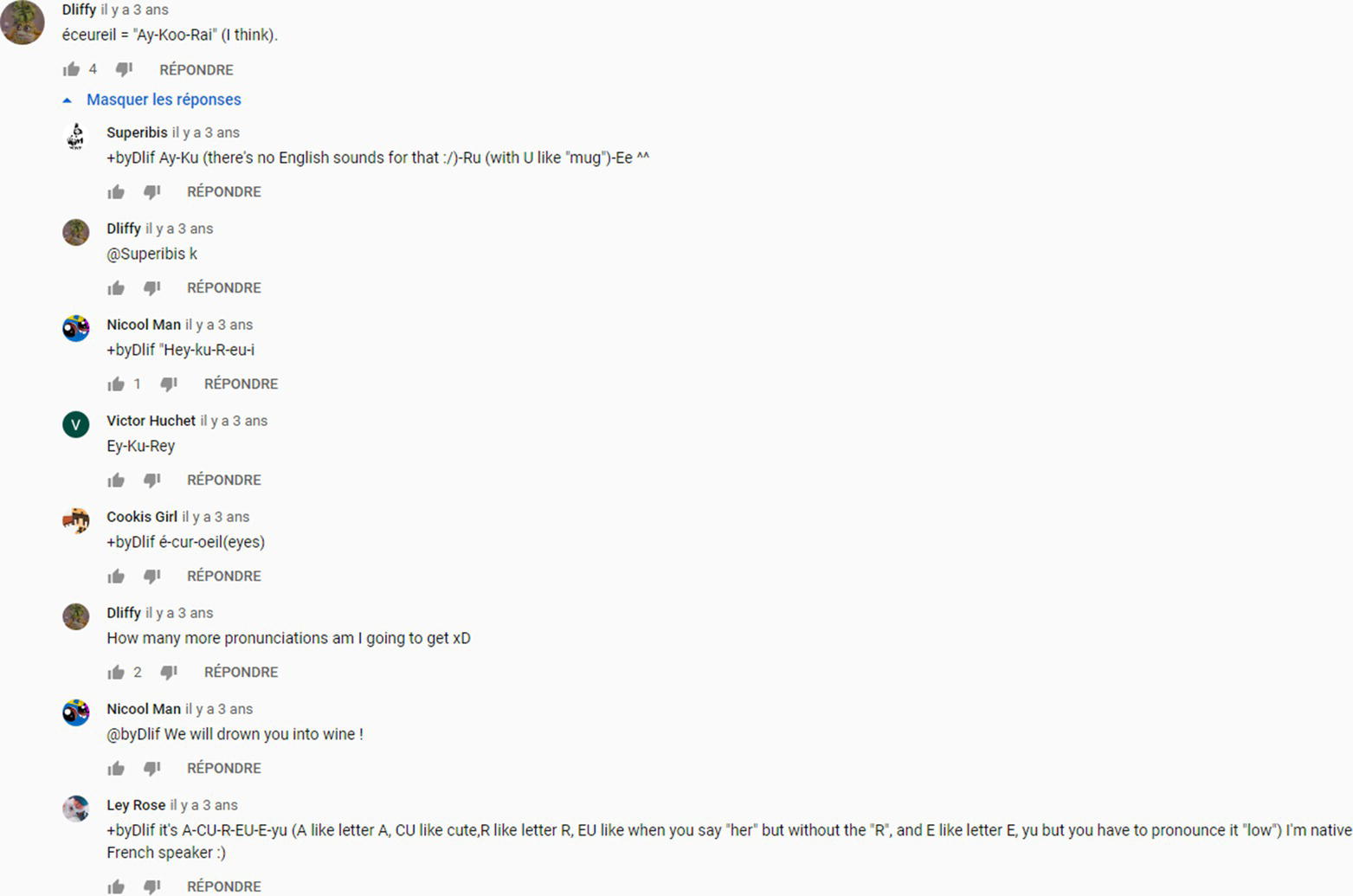

Internet users interact with each other (often much more than with the vlogger) and they form an ephemeral or regular mini‐community of interactants around the vlog. These exchanges are often multilingual in the globalized sphere of the internet and, during the exchanges, users challenge each other, answer each other, inform each other and give each other advice. In an example, some of which can be seen in Figure 10.3, we observed 36 answers in English. The exchange included difficulties in pronouncing the sound th in English and nasal sounds in French.

It is also interesting to note that from the difficulties of pronunciation in one language, internet users exchange and collaborate on difficulties in other languages, especially English. As internet users communicate in one or more languages, metareflexivity is also much more present. The wide demographic of individuals present on the YouTube platform should also be taken into account. However, it is difficult, given the limited information we have about the vlogger's interlocutors, to build an understanding, based only on a semio‐discursive analysis, of who they are and what their motivations might be: English speakers writing in French or English, Francophones writing in French or English, or anglophones interested in learning French. However, it appears that a microcommunity of linguistic support is being formed and that informal peer learning is taking place. The vlog becomes a space for collaboration and heterolearning between peers. Internet users correct the vlogger and help him improve his French in comments that deal with grammar.

Figure 10.3 Exchanging comments on pronunciation (extract).

Note: Please search the comments by using the keywords Your French is phenomenal in https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uJ3X7Zjy2iM

In his video, Argot Américain (American Slang at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JWWUcQsMcHY), the vlogger, Michael, turns into an English teacher (in his variation of American slang). This informal education is highly appreciated by internet users. This is perceived as more interesting than what is done in formal school environments:

Ah, enfin quelqu'un qui nous apprend l'argot, c'est pas à la fac en licence d'anglais qu'ils nous l'enseigne :p (Ah, finally someone who doesn't teach us slang like they have a bachelor's degree in English :p)

Multimedia and digital literacy skills and creativity

Vlogs are a digital genre that develops on multimodal interactive platforms, so they represent an opportunity for vloggers to acquire digital literacy skills while focusing on their words and gestures, but also by reworking their media product during editing and by embedding video effects, text, artistic effects, images or photos, emoticons. We thus observe informal learning in multimedia literacy and a variation of creative expression. Vlogs can be a place for exchanges of best practices about videos with various content. Experienced vloggers also develop digital marketing skills by managing a channel and recommendations via the YouTube Creator Studio (see Figure 10.4).

YouTube Creators gives vloggers the ability to broadcast live, manage a community, study its analytics, and translate and subtitle videos. They also acquire legal awareness from the rules of the concept of copyright and the right of dissemination (legal concepts).

Intercultural exchanges

Vlogs are also conducive to exchanges on cultural aspects, even assertions or challenges and conflicts of opinion around stereotypes. Michael's video on the differences between France and the United States (Les différences entre la France et les USA; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IIQa5sPPIqI) is particularly representative of these exchanges in a globalized space. As Michael points out, these are his own observations, a list of “noted” differences (in capital letters under his video) between France and the United States. This list is therefore subjective and gives rise to various comments in which the different internet users express their cultural point of view on the question. Thus, one user takes each of the points developed by Michael and positions himself in relation to these points, giving his view on topics such as the school system in France, cigarette smoking, high school, and television.

Cultural topics seem to be conducive to discussions and we can observe one comment in particular that users engage with – food. If the initial comment indicated a stereotype, “America is famous for having a lot of obese people (at the same time given the number of fastfood is not very surprising!),” other comments have followed questioning these affirmations, and finally the discussion evolves more widely toward the food in fast‐food restaurants or in other restaurants. We observe in this polylogue a discussion around representations, including for Francophones. The argumentative dimension is, moreover, significant. Internet users give opposing points of view (“yes that's exactly it!”; “I do not agree”) and give different arguments with examples (“Studies have shown that a meal in fastfood is less caloric than in a restaurant for example”; “on the contrary in a restaurant you put as much salt and there is plenty of sauce etc.”).

Figure 10.4 YouTube Creator Studio dashboard.

Limits of informal learning in the context of vlogs

From a pedagogical point of view, when introducing language learners to vlogging, teachers must help students understand the unique context in which they are practicing their language ability, while also developing their digital literacy skills and creativity. For these reasons, we suggest class activities such as creating a list of each person's informal learning practices and talking about possible linguistic or cultural learning related to these activities, or letting the learners lead activities on these topics. This would represent an important step toward the recognition of skills acquired in an informal context for teachers who are not yet engaged in such approaches.

However, there are several limitations to possible informal learning through YouTube: the limitations of publishing on the YouTube platform, the diversity of skills or the cultural diversity that we encounter on this platform, crystallized global identity tensions among users, and bullying and trolling.

The limits of publishing on YouTube

The limits set up by the YouTube platform itself are centralized for business purposes, for data protection, and for legal aspects. Individuals may also decline for ethical reasons to post to YouTube. Other alternatives are possible for vlogging but do not offer the possibility of an audience base as wide as YouTube. Vloggers may also be attracted by opportunities offered by alternative platforms and up and coming decentralized social networks powered by blockchain technology.

The limits of language learning on YouTube™

First of all, as has already been shown in another context of informal language learning – within communities such as Busuu or Livemocha (Potolia et al. 2011) – the question of explanation, the correction made, and the competence of those who give it, remain open. For example, in Figure 10.5, we can observe random corrections, competency of users in making corrections, and the limits of peer learning. Thus, a new skill, that of knowing how to validate the relevance of information on the internet, needs to be incorporated in the practice of informal language learning.

Interpersonal and intercultural tensions

It appears that a topic such as “The Differences between France and the US” crystallized global identity tensions among those who presented themselves as Michael's French audience, and who commented on what they perceived to be an American identity, French identity, and regional identities in France. These constructed identities, however, were perceived in a more superficial way by his audience, who appeared to characterize him as an individual with an American accent and Asian origins, apparently based on their own experiences and interests. However, identities on YouTube are subjective and transitory.

Figure 10.5 Corrections offered by users on YouTube.

Note: Please search the comments by using the keywords éceureil = “Ay‐Koo‐Rai” in https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uJ3X7Zjy2iM

Conclusion

Throughout this chapter we have described the emergence of the professionalization of vloggers. Vlogging came into existence as a conscious imitation of blogs and in response to new standards of presenting information through videos. English content is predominant on YouTube and coverage of other languages remains uneven (Benson 2017). As a result, YouTube has a basic economic supply and demand problem. Whilst English language could lead to a larger audience, viewers also have access to a larger surplus of English channels. Vlogs for language learning could deliver an “efficient technology‐based model that can effectively deliver the current consumer demand for language learning” (British Council 2018, p. 7).

Finally, the new economy, which is characterized by sharing content, challenges traditional education and language learning. Emerging technologies offer opportunities for new ways of vlogging, where vloggers could abandon a centralized platform such as YouTube which can censor content, in favor of decentralized media platforms.

REFERENCES

- Alrasheedi, M. and Capretz, L.F. (2013). Developing a mobile learning maturity model. International Journal for Infonomics (IJI) 6 (3/4): 771–779.

- Anderson, M. and Jiang, J. (2018). Teens, Social Media, and Technology 2018. Pew Research Center: Internet and Technology. Accessed 23 February 2019. http://www.pewinternet.org/2018/05/31/teens‐social‐media‐technology‐2018.

- Barrett, N.E. and Liu, G.‐Z. (2016). Global trends and research aims for English academic oral presentations: changes, challenges, and opportunities for learning technology. Review of Educational Research 86 (4): 1227–1271.

- Barton, D. and Lee, C. (2013). Language Online: Investigating Digital Texts and Practices. New York: Routledge.

- Benson, P. (2017). The Discourse of YouTube: Multimodal Text in a Global Context. Routledge, Taylor and Francis.

- Bezemer, J. and Kress, G. (2015). Multimodality, Learning and Communication: A Social Semiotic Frame. London: Routledge.

- Bozkurt, A. and Ataizi, M. (2015). English 2.0: learning and Acquisition of English in the networked globe with the Connectivist approach. Contemporary Educational Technology 6 (2): 155–168.

- British Council (2018). The Future Demand for English in Europe: 2025 and beyond. British Council. Accessed 23 February 2019. https://www.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/future_demand_for_english_in_europe_2025_and_beyond_british_council_2018.pdf.

- Burgess, J. and Green, J. (2018). YouTube: Online Video and Participatory Culture. Oxford: Wiley.

- Burston, J. (2015). Twenty years of MALL project implementation: a meta‐analysis of learning outcomes. ReCALL 27 (1): 4–20.

- Celik, C. and Develotte, C. (2011). L'Analyse de Discours: Exemple d'une Communication Pédagogique Médiée par Ordinateur [asynchrone] [Speech analysis: Example of a computer‐mediated pedagogical communication [asynchronous]]. In: Guide pour la recherche en didactique des langues et des cultures, Approches contextualisées (eds. P. Blanchet and P. Chardenet), 92–99. Paris: Éditions des Archives Contemporaines.

- Codreanu, T. and Combe, C. (2018). Glocal tensions: exploring the dynamics of intercultural communication through a language learner's vlog. In: Screens and Scenes: Multimodal Communication in Online Intercultural Encounters (eds. R. Kern and C. Develotte), 40–61. London: Routledge.

- Combe Celik, C. (2014). Vlogues on YouTube: a new kind of multimodal interactions. In: Proceedings of the Colloquium Multimodal Interactions by Screen 2014 (eds. I.C. de Carvajal and M. Ollagnier‐Beldame), 265–280. Accessed 23 2019. https://impec.sciencesconf.org/conference/impec/pages/Impec2014_Combe_Celik.pdf.

- Cong‐Lem, N. (2018). Web‐based language learning (WBLL) for enhancing L2 speaking performance: a review. Advances in Language and Literary Studies 9 (4): 143–152.

- Council of Europe. (2018). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Council of Europe. Accessed 23 February 2019. https://rm.coe.int/cefr‐companion‐volume‐with‐new‐descriptors‐2018/1680787989

- Cross, J. (2006). Informal Learning: Rediscovering the Natural Pathways that Inspire Innovation and Performance. Oxford: Wiley.

- Derakhshan, A. and Khodabakhshzadeh, H. (2011). Why CALL why not MALL: an in‐depth review of text‐message vocabulary learning. Theory and Practice in Language Studies 1 (9): 1150–1159.

- Develotte, C. (2012). Analysis of online multimodal corpora: state of play and perspectives. SHS Web of Conferences 1: 509–525.

- Develotte, C., Guichon, N., and Vincent, C. (2010). The use of the webcam for teaching a foreign language in a desktop videoconferencing environment. ReCALL 23 (3): 293–312.

- Ducate, L., Lomicka, L., and Lord, G. (2012). Hybrid learning spaces, re‐envisioning language leaning. In: AAUSC 2012 Volume‐Issues in Language Program Direction: Hybrid Language Teaching and Learning: Exploring Theoretical, Pedagogical and Curricular Issues (eds. F. Rubio, J.J. Thoms and S.K. Bourns), 67–91. Boston: Cengage Learning.

- Flew, T. (2005). New Media: An Introduction, 2e. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

- Flichy, P. (2010). Le Sacre de l'amateur. Sociologie des passions ordinaires à l'ère numérique. La République des Idées. Seuil.

- Guerin, M., Cigognini, M., and Pettenati, M. (2010). Learner 2.0. In: Telecollaboration 2.0: Language, Literacies, and Intercultural Learning in the 21st Century (eds. S. Guth and F. Helm), 166–198. Bern: Peter Lang.

- Guichon, N. and Cohen, C. (2016). Multimodality and CALL. In: The Routledge Handbook of Language Learning and Technology (eds. F. Farr and L. Murray), 509–521. London: Routledge.

- Hauck, M. (2010). Telecollaboration: at the interface between multimodal and intercultural communicative competence. In: Telecollaboration 2.0: Language, Literacies and Intercultural Learning in the 21st Century (eds. S. Guth and F. Helm), 219–244. Bern: Peter Lang.

- Hoechsmann, M. and De Waard, H. (2015). Définir la Politique de la Littératie Numérique et la Pratique dans le Paysage de l'Education Canadienne. MediaSmarts. Accessed 23 February 2019. https://habilomedias.ca/sites/mediasmarts/files/publication‐report/full/definir‐litteratie‐numerique.pdf.

- Hung, S.‐T. (2011). Pedagogical applications of Vlogs: an investigation into ESP Learners' perceptions. British Journal of Educational Technology 42 (5): 736–746.

- Jarvis, H.A. and Achilleos, M. (2013). From computer assisted language learning (CALL) to Mobile assisted language use. TESL‐EJ 16 (4): 1–18.

- Jee, M.J. (2011). Web 2.0 technology meets mobile assisted language learning. The IALLT Journal of Language Learning Technologies 41 (1) International Association for Language Learning Technology. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/274457938_Web_20_Technology_Meets_Mobile_Assisted_Language_Learning.

- Jewitt, C. and Kress, G. (2003). Multimodal Literacy. New York: Peter Lang.

- Jewitt, C., Bezemer, J., and O, Halloran, K. (2016). Introducing Multimodality. New York: Routledge.

- Jones, R.H. and Hafner, C.A. (2012). Understanding Digital Literacies. New York: Routledge.

- Kress, G. (2003). Literacy in the New Media Age. London: Routledge.

- Kress, G. (2004). Reading images: Multimodality, representation and new media. Information Design Journal 12 (2): 110–119.

- Lacelle, N., Boutin, J.‐F., and Lebrun, M. (2012). La Littératie Médiatique Multimodale de Nouvelles Approches en Lecture‐Ecriture à l'Ecole et hors de l'Ecole [Multimodal Media Literacy of New Approaches in Reading‐Writing at School and Out of School]. Québec: Presses de l'Université du Québec.

- Lacelle, N., Boutin, J.‐F., and Lebrun, M. (2018). La Littératie Médiatique Multimodale Appliquée en Contexte Numérique – LMM@. Outils Conceptuels et Didactiques. Québec: Presses de l'Université du Québec.

- Leadbeater, C. and Miller, P. (2004). The pro‐am revolution. In: How Enthusiasts Are Changing our Economy and Society. London: Demos.

- Lien, F. P. (2012). Communicative acts and identity construction on YouTube first‐person vlogs: The case of English‐speaking teenagers. Unpublished MPhil thesis. The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

- Lockhart, A.S. (2016). Non‐formal and Informal Programs and Activities that Promote the Acquisition of Knowledge and Skills in Areas of Global Citizenship Education (GCED) and Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). UNESDOC: UNESCO Digital Library. Accessed February 23, 2019. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000245625.

- Maldin, S.A., Reza, S., and Rezeki, I. (2017). Stepping up the English speaking proficiency of hospitality students through video blogs (Vlogs). Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research (ASSEHR) 148: 68–53.

- Marsick, V.J. and Watkins, K. (1990). Informal and Incidental Learning in the Workplace. London: Routledge.

- Maulidah, I. (2017). Vlog: the means to improve students' speaking ability. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research 145: 12–15.

- Millerand, F., Proulx, S., and Rueff, J. (2010). Web Social: Mutation de la Communication. Québec: Presse de l'Université du Québec.

- OECD (2016). Recognition of Non‐Forma and Informal Learning—Home. OECD. Accessed 23 February 2019. http://www.oecd.org/education/skills‐beyond‐school/recognitionofnon‐formalandinformallearning‐home.htm.

- Paveau, M.‐A. (2017). L'Analyse du Discours Numérique. Paris: Hermann.

- Potolia, A., Loiseau, M., and Zourou, K. (2011). Quelle(s) pédagogie(s) voi(en)t le jour dans les (grandes) communautés Web 2.0 d'apprenants de langue? Actes de la conférence EPAL 2011 [What pedagogy(s) do you see emerging in the (large) Web 2.0 communities of language learners?]. In: Proceedings of the EPAL 2011 conference, 19–22. http://w3.u‐grenoble3.fr/epal/dossier/06_act/pdf/epal2011‐potolia‐et‐al.pdf.

- Rogers, A. (2004). Looking again at non‐formal and informal education: towards a new paradigm. In: The Encyclopedia of Informal Education, vol. 2, 158–159. Infed.

- Santamaria‐Garcia, C. (2018). Connected learners: online and off‐line learning with a focus on politeness intercultural competences. In: Cross‐Cultural Perspectives on Technology‐Enhanced Language Learning, 83–99. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Seitzinger, J. (2006). Be constructive: blogs, podcasts, and wikis as constructivist learning tools. In: The eLearning Guild's Learning Solutions e‐Magazine. Accessed 23 February 2019.

- Son, J.‐B. (2018). Technology in English as a foreign language (EFL) teaching. In: The TESOL Encyclopedia of English Language Teaching, 1–6. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Stockwell, G. (2007). Vocabulary on the move: investigating an intelligent Mobile phone‐based vocabulary tutor. Computer Assisted Language Learning 20 (4): 365–383.

- Stockwell, G. and Hubbard, P. (2013). Some emerging principles for mobile‐assisted language learning. In: The International Research Foundation for English Language Education, 1–15. Accessed 23 February 2019. http://www.tirfonline.org/wp‐content/uploads/2013/11/TIRF_MALL_Papers_StockwellHubbard.pdf.

- The New London Group (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review 66 (1): 60–93.

- Tissot, P. (2004). Terminology of Vocational Training Policy: A Multilingual Glossary for an Enlarged Europe. Luxembourg: CEDEFOP.

- Toffoli, D. and Sockett, G. (2010a). How non‐specialist students of English practice informal learning using web 2.0 tools. ASp. la revue du GERAS 58 (20): 125–144.

- Toffoli, D. and Sockett, G. (2010b). University teachers' perceptions of online informal learning of English (OILE). Computer Assisted Language Learning 28 (1): 7–21.

- Watkins, J. and Wilkins, M. (2011). Using YouTube in the EFL classroom. Language Education in Asia 2 (1): 113–119.

- Wolcott, H.F. (1995). The Art of Fieldwork. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press.