23

Translanguaging Across Contexts

SARAH J. McCARTHEY IDALIA NUÑEZ AND CHAEHYUN LEE

Introduction

In the last 10 years, the term translanguaging has gained prominence among bilingual educators. While the phenomenon of speakers shuttling between and among languages has been documented from historical times, García and Leiva (2014) have clarified the term as both an act of bilingual performance and a pedagogical approach to teaching. A distinction between the spontaneous use of two languages and the intentional practice of alternating between languages for pedagogical purposes has been made by Cenoz and Gorter (2017). Cenoz (2017) elaborated upon the distinction, “Pedagogical translanguaging is planned by the teacher inside the classroom and can refer to the different languages for input and output or to other planned strategies based on the use of students' resources from the whole linguistic repertoire. Spontaneous translanguaging refers to fluid discursive practices that can take place inside or outside the classroom” (p. 194).

In this chapter, we outline the historical context, definitions, and the underlying theory of translanguaging before identifying several critiques. The literature review includes studies of translanguaging within formal educational settings and then focuses on research conducted in families and communities (informal settings). We analyze examples from two of the authors' language data (Spanish and Korean) to demonstrate current translanguaging practices across settings. Finally, we provide implications for further research and pedagogy.

Context and theory

Historical context of translanguaging

The historical development of translanguaging is documented by Lewis et al. (2012) who cite Williams's (1994) use of a Welsh word to indicate the systematic and planned use of two languages within the same lesson. While translanguaging is conceptualized as a pedagogic theory and practice with important educational outcomes, Williams (1994) argues that it represents an underlying cognitive process that requires a deeper understanding of concepts than merely translating.

Translanguaging as a term and theory is rooted in an ideology that embraces bilingualism and reacts against the notion of language compartmentalization and separation. For example, the historical portrayal of Welsh and English as being in conflict with one another due to oppression by one group gave way to increased understandings of the advantages of being bilingual in the late twentieth century (Lewis et al.). Thus, translanguaging represents the advantages of bilingualism for communication, cognition, and language production and represents a move away from distinctions between first and second language learning as well as hierarchical conceptions of language use. The term also suggests that speakers of more than one language do not separate their languages in home, street, or school settings but use languages strategically to attain specific purposes; thus, translanguaging can be used as a strategy to retain and develop knowledge (Williams 1994). Translanguaging highlights the value of bilingualism in itself rather than as a transition to a majority language (MacSwan 2017) and celebrates multilingual competence (Canagarajah 2011a).

For Canagarajah (2011a) translanguaging overlaps with terms from different disciplines: code‐meshing in composition, multiliteracies in new literacy, pluralingualism in applied linguistics, and fluid lects in sociolinguistics. While there are differences in application, the underlying commonality is challenging a Chomskian orientation of language learning as innate, monolingual, and occurring in a homogeneous environment. Instead, bilingual learners shuttle between languages to co‐construct meaning and utilize creative improvisation within social practices.

Theory

In her 2009a book, García focuses on translanguaging as a process and an educational approach. She wrote, “Translanguaging is an approach to the use of language, bilingualism, and the education of bilinguals that considers the language practices of bilinguals not as two autonomous language systems as has been traditionally the case, but as one linguistic repertoire with features that have been socially constructed as belonging to two separate languages” (p. 2). She argued that students engage in the multimodal process of translanguaging as they read, write, take notes, discuss, and use signs in and outside classrooms. As an educational approach, students are using diverse language practices in their learning while teachers use inclusive language practices. The translanguaging approach contrasts with dual immersion and other bilingual programs because it does not advocate separating language instruction or controlling language use in specific settings; rather, all of the children's semiotic and language practices are utilized for meaning‐making. Pedagogical practices identified by García to promote translanguaging include (i) translation to differentiate among students' levels; (ii) collaborative dialogue and grouping, reading, and listening to multilingual texts, and project learning to build background knowledge; (iii) promotion of inner speech and multilingual writing to deepen understanding; (iv) text comparison using cognates, word walls and sentence starters to support cross‐linguistic transfer and metalinguistic awareness; and (v) alternating media and language use and translating to encourage cross‐linguistic flexibility. These strategies also support learners in interrogating social inequalities. Baker (2011) found that translanguaging has several advantages as an approach to education: promoting a deeper understanding of the subject, developing the weaker language, facilitating home–school links, and integrating fluent speakers with early learners.

The theory underlying translanguaging as an approach to education is further developed in García and Wei (2014); they use Bakhtin's (1975) conception of heteroglossia suggesting that language is bound to context. Drawing from Maturana and Varela (1987) and Becker (1991) who proposed the idea of “languaging” to indicate an ongoing creative process that occurs within a social context, they propose a view of language that challenges the structuralist theories of Chomsky (1965) and Saussure (1916). García and Wei propose “dynamic bilingualism” that challenges traditional notions of bilingualism as involving two autonomous linguistic systems and Cummins's (1981) view of linguistic interdependence between the two systems. By theorizing that there is only one linguistic system, García and her colleagues agree with Grosjean's (1982) argument that bilinguals are not two monolinguals existing in one person. Bilinguals select features from their linguistic repertoires based on context within “a single array of disaggregated features that are always activated” (García and Otheguy, cited in García and Wei 2014, p. 15). García and Wei further note that speakers may act as though they are monolingual due to societal pressures but that does not mean they have two separate systems.

García and Wei assume that bilingualism is the norm and that bilinguals engage in translanguaging practices to make sense of their worlds. For example, speakers in multilingual families select from their repertoires to communicate about events depending on the interactions and contexts. Embracing creativity (the ability to follow or flout language rules and norms) and criticality (the ability to use evidence to question and respond reasonably), translanguaging recognizes the complexity of spaces and resources used by language users (Wei 2011). Thus, “translanguaging is transformative and creates changes in interactive cognitive and social structures” (García and Wei, p. 42) providing opportunities for speakers to go beyond traditional structures and disciplines and “generate more just social structures, capable of liberating the voices of the oppressed” (p. 42). They argue that translanguaging differs from code‐switching because it assumes one integrated system. In a further elaboration of differences between code‐switching and translanguaging, García and Lin (2017) note that translanguaging focuses on the speakers' use of languages rather than the perspective of the “named languages” (p. 120).

The conceptual shift represented by translanguaging is away from the notion of transfer of language use toward a theory of integration of language practices. Canagarajah (2011a) argues that translanguaging represents a move toward having students access their entire language repertoire not only for speaking, but for writing and developing linguistic abilities for different functions; the concept implies repertoire‐building rather than total mastery of each language. Translanguaging requires social sensitivity and linguistic selectivity within a short time; the term reflects the language flexibility of speakers in South Africa who use multiple languages flexibly rather than the term “mother tongue” (Makelela 2015).

Critiques of theory

The term and underlying theory of translanguaging are not without critics. Some scholars believe the use of translanguaging strategies can be a threat to heritage language preservation. For example, Cenoz and Gorter (2017) cite the concern of Basques who have seen their language change from one that was mocked in the 1950s to one that has gained status and is the language of instruction in schools. Critics of translanguaging practices fear that the quality of Basque suffers when it is mixed with Spanish and that Basque may once again disappear. The issues cited by Basque speakers reflect a concern of speakers of many minority languages that encouraging language‐meshing will increase pressure to switch to a majority language that can, once again, threaten the survival of minority languages. However, Cenoz and Gorter argue that the wider social context is important to consider and that translanguaging should be seen as an opportunity rather than a threat. Creating spaces where only the minority language is spoken, offering examples in both languages without direct translation, promoting metalinguistic awareness and awareness of language status, as well as making the link between spontaneous translanguaging and intentional classroom translanguaging practices can contribute to maintaining the use of more than one language. Canagarajah (2011a) addresses the social critique of the loss of minority languages by suggesting the theory actually gives voice to all language users and can represent more complex identities than the focus on heritage language use.

MacSwan (2017) provides a critique from a linguistic perspective of García and Wei's theory of translanguaging. He argues that the concept of a unitary, undifferentiated, internal language system is at odds with data that demonstrate the developmental independence of syntax and phonology in two different registers and highlights the finding that speakers attribute different properties to English and Spanish. He proposes an integrated multilingual model that includes internal differentiation, introduces the idea that everyone is multilingual due to their ability to shift registers appropriately, and argues that schools should encourage students to make full use of their linguistic repertoires, an idea shared by proponents of translanguaging.

Empirical studies

Most of the empirical studies on translanguaging have been conducted in formal educational settings ignited by Creese and Blackledge's (2010) ethnographic studies of students' language practices in complementary schools (also called heritage language or community schools). However, translanguaging occurs in multiple settings; increasing attention has been given to documenting its utility in homes and communities as children and parents engage in informal language learning. Our review presents studies in both formal educational settings and informal, out of school settings such as homes and communities.

Translanguaging in formal settings

Creese and Blackledge (2010) found that teachers and students used the heritage language (Gujarati, Mandarin, Cantonese) and English to clarify tasks, for lesson accomplishment, and to identity performance. The teachers tended to be more proficient in the community language and their phrases were often taken up by students; however, the students, who tended to be more proficient in English, used their bilingualism to question and challenge the teachers. Studies conducted with elementary Spanish‐English bilinguals in dual language classrooms have focused on the teachers' implementation of instructional strategies; code‐switching, code‐mixing, translating, and using cognates to scaffold students' language development in both languages have encouraged language learning (e.g. Esquinca et al. 2014; Gort and Sembiante 2015; Palmer et al. 2014; Worthy et al. 2013).

Although the term translanguaging often referred to the teacher's pedagogical practices in bilingual classrooms to scaffold bilingual children's language and literacy development (Canagarajah 2011a), an increasing number of researchers have examined how bilingual learners engaged in translanguaging practices in classroom settings. The findings demonstrate that the emergent bilinguals are able to utilize their complete language repertoires orally (Durán and Palmer 2014; Martin‐Beltran 2010; Sayer 2011) and during writing (Bauer et al. 2017; Gort 2012; Velasco and García 2014).

Bilingual students' oral translanguaging

In a study of kindergartners in a Spanish‐English two‐way dual language program, García (2009b) found that children used translanguaging for several metafunctions including to co‐construct meaning of others, to construct meaning within themselves, to include or exclude others, and to demonstrate knowledge. She noted that students used all their linguistic resources, communicated across languages, and combined multimodal signs. Durán and Palmer (2014) investigated first‐grade Spanish bilingual students' language use in two‐way immersion bilingual classrooms. The researchers reported that when the classroom teachers provided space for Spanish when the instruction was supposed to be in English and vice versa, the participating students used translanguaging in an appropriate and meaningful way to engage in classroom interactions. For instance, the students' use of translanguaging was accepted by their peers during bilingual pair time, when students worked together primarily without the teacher's guidance. The students self‐positioned their roles as language learners or language experts during bilingual pair times by using their language resources through translanguaging in a natural manner. Thus, translanguaging was a normalized practice in the classroom.

Similarly, Martin‐Beltran (2010) examined fifth‐grade Spanish‐speaking bilingual students' classroom interactions in a dual‐language program. The students' language use in the classroom revealed that they used translanguaging when engaged in collaborative dialogue by drawing on their bilingual resources to understand unfamiliar concepts. The findings further revealed that the students' translanguaging promoted their metalinguistic awareness since they often engaged in private speech by utilizing both languages as a verbal problem‐solving process. Sayer (2011) analyzed the specific functions of bilingual students' translanguaging in a second‐grade bilingual classroom where TexMex, a language blending of Spanish and English as a bilingual vernacular, is used in a Mexican American community. Sayer found that the teacher and students often participated in translanguaging practices through TexMex. The students translanguaged for different functions such as checking comprehension and code alignment. The bilingual students purposefully used translanguaging through TexMex to make sense of their language use and to actively participate in bilingual discourse practices. In an ethnographic study of a kindergarten/first‐grade classroom within a Spanish‐English dual language strand, Martinez et al. (2017) found that students' translanguaging practices intersected with how they asserted, contested, and negotiated their identities within classroom talk. For example, the practice of alternating Spanish and English in particular exchanges during classroom discussions signaled solidarity and enabled certain students who were learning Spanish to position themselves as bilingual like their Latinx peers.

Focusing on focal children in a first‐grade classroom, García‐Mateus and Palmer (2017) found that translanguaging offered empowering language and educational opportunities to minoritized, bilingual children. The teacher opened up spaces that allowed students to develop cross‐linguistic awareness. When the bilingual students' languages were valued and validated in the classroom, each individual was more likely to utilize his or her full linguistic repertoires to create a classroom environment where bilingualism was welcomed. The classroom environment and the teachers' affirmation of translanguaging helped the bilingual students to understand that the classroom was a place to utilize their complete language repertoires. Additionally, when students used translanguaging within dual‐language classrooms, they represented their multilingual identities in relation to peers' language use.

Studies with older students have focused on the use of translanguaging in peer‐to‐peer interactions. Duarte (2016) studied four high schools in mathematics and social sciences classes in Germany where students spoke eight different languages and found that students were on task in their translanguaging sequences, engaging in cognitively demanding speech acts. Using video data from sequences involving 51 students, researchers coded individual speech acts to focus on language use (German, two other languages, or a mix of German and other languages) and type of talk (on‐ or off‐task). Translanguaging was used to scaffold meaning through interactions to solve tasks. The author concluded, “Translanguaging practices thus seem to reinforce the creative process of knowledge building, by mediating the emergence of high‐order thinking” (p. 13).

Exploring a ninth grade, English medium of instruction (EMI) class in Hong Kong with 14 Pakistani and Indian students and an English‐Cantonese speaking teacher, Lin and He (2017) focused on naturally occurring translanguaging practices. Although the school policy was to speak in English, the teacher and students engaged in translanguaging practices, both oral and written, to make meaning within a science lesson. The teacher's non‐punitive stance toward students who were using their home languages to understand the concepts, and her use of some shared words in Cantonese enabled students to use their multilingual repertoires. Students' identities as multilingual speakers were also affirmed when the students taught the teacher specific words in Urdu related to concepts they were studying. Translanguaging allowed students to develop a rapport with the teacher as well as scaffold their learning from each other. The authors argue that the complex flow of speech and gestures across languages occurs naturally and should be encouraged to make a space for meaningful learning; their data challenge the prevailing view of communicating only in the EMI.

Emergent bilingual writers' translanguaging

The majority of the translanguaging studies have paid attention to bilinguals' speech rather than their literacy practices (Smith and Murillo 2015). However, a few researchers have investigated elementary bilingual students' translanguaging during writing and have reported that young emergent bilingual writers also engaged in translanguaging in their biliteracy development (Velasco and García 2014).

The traditional biliteracy studies in writing showed evidence of emergent bilingual writers' use of translanguaging during their writing process, although their writing was produced in only one language (e.g. Edelsky 1986; Lanauze and Snow 1989). Recently, several researchers have focused on the presence of translanguaging when bilinguals plan their writing and compose (Bauer et al. 2017; Gort 2012; Velasco and García 2014). Gort (2012) examined the patterns of first‐grade emergent Spanish‐English bilingual students' code‐switching as an example of translanguaging, when they engaged in writing‐related talk. Her findings revealed that the bilingual students strategically utilized their language repertoires orally from their two languages while writing texts, which supported them to reflect and evaluate their own writing. Because the students used their dual‐language repertoires as they engaged in bilingual interactions to carry out their writing tasks, translanguaging practices appeared during their writing process. However, it is unknown how they actually engaged in translanguaging practices in their written product.

A later study by Velasco and García (2014) explored how K‐4 grade Korean‐English and Spanish‐English bilingual students in dual language programs demonstrated translanguaging in their actual compositions. The participating students revealed that they were able to use their entire linguistic repertoires when presenting their written texts, although the instruction was in one language. Velasco and García found that the bilingual writers used translanguaging in different writing stages including in planning, drafting, and producing their final compositions. These bilingual writers utilized translanguaging as a unique strategy to write and solve problems independently. The findings suggest that translanguaging is a strategy that emergent bilinguals use to make sense of their language use and develop their literacy learning.

Smith et al. (2017) used the term multimodal codemeshing to document the processes of eighth‐grade bilingual students as they designed and presented a multimodal project on a personal hero. Analyses of the computer screen recordings, artifacts, videotaped observations, and interviews showed that students' processes were complex and iterative as they used texts, sound, visuals, and movement. Students alternated English with their home language (e.g. Kurdish, Spanish, Vietnamese) while reading, writing, and recording. The digital project afforded the use of multiple languages; students' use of multilingual resources increased over the length of the project as they refined their rhetorical goals. The study highlights the importance of context and task in encouraging students to use their translanguaging strategies.

In an ethnographic study using diaries and diary‐based interviews of multilingual students in a Swedish international school, Jonsson (2013) found that students used translanguaging for several purposes including for jokes or expressing feelings, and when they needed a word in a particular language to make a point. Students tended to translanguage with friends and family who used translanguaging, but tended to separate their languages when speaking with those who were not bilingual or comfortable translanguaging. Their linguistic repertoires were fluid, hybrid, and characterized by awareness of audience including teachers who did not support translanguaging. Their literacy practices reflected use of English and Swedish and their language use was more separated in school than for pleasure reading; their choices were affected by access as well. In online and media use, students used English and Swedish primarily but also made use of their other languages such as Arabic. While the school policy did not embrace the students' translanguaging practices, students were self‐reflective about their language use.

Some educators take the position that translanguaging is not appropriate in writing (Barbour 2002), because it is considered a more formal context than speaking. However, Canagarajah (2011b) has challenged this view and conducted research demonstrating the positive effects of translanguaging with college students. In an ethnographic classroom study of a Saudi Arabian college student who mixed Arabic, French, and English, Canagarajah (2011b) identified four code‐meshing/translanguaging strategies used over multiple drafts of an essay. Through recontextualization, the student figured out the context including instructor's and peers' receptiveness to code‐meshing. Voice strategies allowed her to both appropriate dominant codes and experiment with language and identity – “she writes, not for a grade but for voice” (p. 406). The student used interactional strategies such as addressing the reader and not translating the Arabic to change the readers' perspectives and point out the esthetics of texts. Her textualization strategies were apparent through her performative orientation and choices throughout the writing process. While Canagarajah argues these strategies can be elaborated upon and taught, he cautions scholars against “glorifying multilingual student communication” (p. 413); sometimes students intentionally code‐mesh, sometimes there are “errors,” and failure to distinguish them can have the effect of not helping students develop their full capabilities of multilingual writing.

An experimental study by Makelela (2015) conducted in South Africa with 60 preservice teachers divided into control and experimental groups demonstrated the positive effects of translanguaging in oral and written modes. The control group was taught in the usual medium of instruction, Sepedi, with use of other languages limited while the experimental group used translanguaging strategies with flexible use of the target language and home languages; the instructor used specific translanguaging strategies such as contrastive elaboration, group discussions with oral and writing activities intended to facilitate use of multiple languages, and assignments to read stories in the home language and retell them in the target language. The translanguaging group outperformed the control group on vocabulary and oral reading tasks and the preservice teachers developed positive associations with their own as well as the target language. The quantitative and qualitative data analyses show that the purposeful shifting of languages when teaching African languages was effective in developing language and literacy skills, and was successful in developing multilingual identities for the preservice teachers. Makelela argues that the results of the study can be used to expand translanguaging strategies to teaching environments for younger learners and programmatic development.

Translanguaging in informal settings: Bi/Multilingual homes and communities

Early language and literacy learning are impacted not only by school experiences, but also by home environments and the community. Seemingly “mundane practices of everyday life” (Rosaldo 1993, p. 217), occurring in the community, can serve as authentic and meaningful language and literacy learning experiences. Researchers centering on the social and cultural ways of doing language and literacy understand that the experiences that children are exposed to at home and in their communities influence their linguistic repertoires (Bartlett 2007; Hall 1998; Heath 1983; Rogoff 1990; Street 1984), especially for children from linguistically and culturally diverse backgrounds. In this section, we consider the literature that has focused on the translanguaging that occurs in home and community contexts.

Studies taking place in home and community spaces have shown that translanguaging is a necessary discursive resource for bilingual children with parents who primarily speak a minority language (Alvarez 2014; Orellana 2009; Orellana et al. 2001, 2003). For example, Orellana et al. (2003) discussed the concept of language brokering, referring to the linguistic process of interpreting and translating from one language to another “between culturally and linguistically different people” (Tse 1995, p. 226, as cited by Orellana et al. 2003, p. 15). In their study, Orellana et al. (2003) demonstrate how in immigrant homes, it was common for children to help their parents by serving as “language brokers” during interactions with adults, teachers, or other institutional representatives. These moments of language brokering occurred when parents received mail, forms, advertisements, and during transactions in English. Children used their linguistic repertoires to interpret and translate from English to Spanish the information their parents needed. Moreover, this linguistic practice helped Spanish‐speaking parents to survive the English‐only context. As García explains from a translanguaging perspective in Orellana and García (2014), when children are doing “language brokering work,” they are essentially drawing “from one linguistic repertoire that then is socially constructed as two autonomous language systems” (387). Thus, language brokering is translanguaging. Alvarez (2014) also theorizes language brokering as a translanguaging event where emergent bilingual youth use their linguistic repertoire to “translate, interpret and mediate oral and written texts during adult‐to‐adult‐conversation” (p. 327). Alvarez examined the translanguaging of bilingual children when they worked on their English monolingual homework in an after‐school program with bilingual mentors and Spanish‐speaking parents collaborating in these events. For these homework experiences, the children were doing language brokering between their parents and the mentor to clarify the meaning of words or to offer alternative meanings during conversations. For example, a participant named Flor clarified the meaning of the word “changos” to her mentor by saying it meant “monkeys.” Ultimately, the children's translanguaging was necessary to mediate and facilitate communication between adults and to support their own sense‐making of academic homework.

In the context of the home, studies have also found that bilingual parents creatively engage in translanguaging to support their children's development of bi/multilingualism and biliteracy. Li (2006) focused on the home language and literacy practices of three Chinese‐Canadian children. Through the use of family portraits, Li revealed that the children's parents were implementing language policies that encouraged their children to use Chinese and English on specific days of the week; they also planned for reading and writing opportunities in both languages such as writing emails in English or practicing writing Chinese characters. These experiences allowed the children to continue to develop their Chinese and English in oral and written forms. Similarly, Volk and de Acosta (2003) noted how Puerto Rican families used both English and Spanish to help their children in English literacy learning. They documented the switching between English and Spanish to create new texts and make sense of words. More recently, Song (2016a,b) highlighted the hybrid literacy practices of a Korean family living in the US. Based on her home visits, Song found that Yoomin's parents used several literacy practices to support her biliteracy development. Through conversations in Korean, video‐chat with her Korean grandmother, and literacy homework from Korean school, Yoomin's parents supported her heritage language literacy learning. They also alternated languages (Korean and English) to facilitate language learning as they translated to make sense of specific words. Ultimately, Song demonstrated that these home hybrid literacy practices were supporting Yoomin's overall biliteracy development.

Through alternation of languages, translating, reading, and writing in two languages, and interpreting across languages, these studies demonstrate that translanguaging in the home context was occurring to create a linguistic environment that supported the development of bi/multilingualism and biliteracy. According to Worthy and Rodríguez‐Galindo (2006), for immigrant parents it is important for their children to be bi/multilingual and biliterate to sustain connections to their cultural and linguistic roots.

Recent studies situated in community or public spaces have also considered translanguaging and the role it plays in supporting bi/multilinguals. Alvarez and Alvarez's (2016) ethnographic study discussed the ways in which immigrant communities in Kentucky nurture and sustain bilingualism outside the school context. Taking place in Valle del Bluegrass Library, their findings demonstrated that the library supported the bilingual Latinx community by creating a safe space, encouraging translanguaging practices, incorporating bilingual materials, providing mentorship, and honoring the literacy practices and text productions of the community. In doing so, the library was meeting the sociocultural needs of the bilingual Latinx community in Kentucky. Similarly, Hua et al. (2017) and Creese et al. (2017) illuminate the role of translanguaging within shops serving bi/multilingual communities. Hua et al. (2017) situated their study in a Polish shop located in London to examine the role of translanguaging. The meaning of translanguaging in this study was inclusive of language, embodied practices, and multimodal resources. They paid particular attention to the various multimodal practices and resources found in that space that marked it as Polish within a different geographic location. Their findings revealed that the Polish shop was a translanguaging space, created by and for translanguaging. For example, the signs or advertisements in the shop were written in Polish and English to connect with customers who spoke Polish or English. The brands and the kinds of goods provided by the shop met the demands of the local Polish community. The authors explained that during transactions and interactions, the manager was translanguaging linguistic and multimodal practices to meet the needs of customers. These multilingual and multimodal resources created a recognized Polish space for the Polish community in London. Creese et al. (2017) identified a butcher's stall in the United Kingdom as a multilingual environment where translanguaging was a resource for providing customer service to multilinguals. The butchers moved among Chinese, Cantonese, Mandarin, and English to meet the demands of customers who regularly came to the market. During the interactions between the butchers and the customers, translations became an important linguistic tool for understanding the customers' orders. The two butchers helped each other by drawing on each other's full linguistic repertoire to assist customers and themselves in navigating daily interactions. Overall, these studies suggest that translanguaging is a practice that occurs in community spaces and supports transactions by meeting the everyday communicative needs of bi/multilingual communities.

Translanguaging examples

Spanish‐English

In this section, we present two examples of translanguaging events (Alvarez 2014) that derived from the data collected for a multiple case study conducted by Nuñez (second author). Her study focused on the everyday language and literacy practices of transfronterizo children on the US–Mexico borderlands. The first example was from Irma García, an emergent bilingual and transfronteriza who lived in Mexico and crossed the US–Mexico border every day to attend US schools. Irma was a second‐grade student enrolled in a late‐exit bilingual education program model that prioritized the transition to the English language by implementing English‐only policies. In other words, throughout the school day, Irma experienced a restrictive language policy that limited her linguistic resources to English. Despite the monolithic policies, Irma strategically found spaces that revealed her bilingual and biliterate practices and identity.

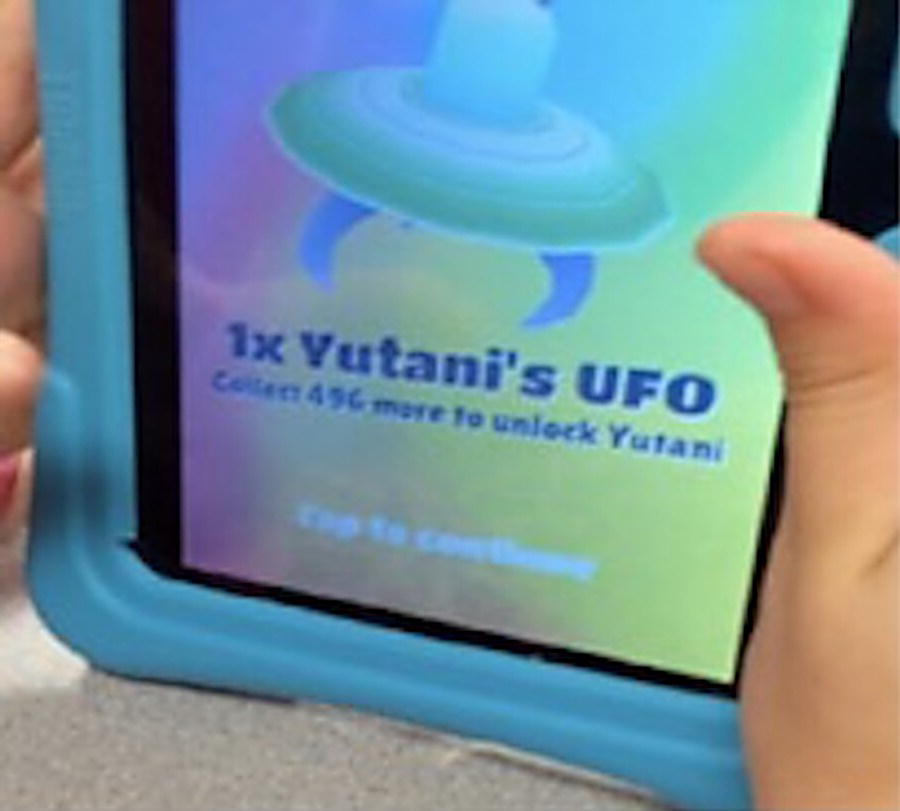

The first translanguaging event took place during the last 10 minutes of a school day, when the classroom teacher announced free time before dismissal. Irma immediately took out her tablet and headphones from her desk to play one of her games. The game seemed to involve Irma in controlling a character on a scooter who had to jump over obstacles and collect coins until the timer ran out or until the character reached the end of the race. If the timer ran out, it was game over, but if she reached the end of the race, it would mean she was the winner. On this particular occasion, Irma had lost the game because time ran out. When she closed the game‐over screen, a screen appeared as shown in Figure 23.1.

The screen read, “Collect 496 more to unlock Yutani.” The phrase “Collect 496 more” referred to how many more coins Irma, as the player of the game, still needed to collect before getting the next character whose name was “Yutani.” As Irma read the screen, she responded to the screen aloud by saying, “Really?! ¿Necesito cuatrocientos noventa y seis para que agarre un monito?” Even though the content on the screen was all in English, Irma used both English and Spanish fluidly to respond to the message. She said “Really?!” using English, to express her disappointment in the message. Then she interpreted the content using Spanish when she said, “¿Necesito cuatrocientos noventa y seis para que agarre un monito? [I need four hundred and ninety‐six so that I can get a character?]” This response demonstrated her understanding of the content in the message and her disappointment in the amount of coins she still needed in order to unlock the next character in her game. García and Sylvan (2011) and Garrity et al. (2015) explain translanguaging as a dynamic discursive regime that bilinguals use in varied ways for meaning‐making purposes and to perform bilingually. Here, Irma was not limiting her linguistic repertoire or her knowledge to just English as was the normal expectation and practice in school. Instead, she was demonstrating how she could draw on her full linguistic repertoire as an emergent bilingual to read and respond to a text. Her thought process and her fluid and dynamic translanguaging were evident in her naturally and unrestrictive bilingual response.

The second example is presented as a fieldnote of the everyday language and literacy practices of Omar Ortega, a transfronterizo emergent bilingual who also lived in Mexico with his family and crossed the border daily to attend school in the US and for other daily activities. In this translanguaging event, Omar was with his mother, Sra. Ortega, and his younger sister, Ariana, who were shopping at H‐E‐B, a popular chain grocery store in the state of Texas. The following is an excerpt from the translanguaging event:

Figure 23.1 A game on a tablet.

Since H‐E‐B was located in the United States, the majority of the products had English labels and/or descriptions. In this translanguaging event, Sra. Ortega was asking Omar to help her find a diet sugar item. Omar read labels and descriptions in English as found in the products to determine which item was diet sugar. As he scanned through the available items, he came across Sweet 'N Low. Omar then informed his mother, “Está dice zero calories, no tiene calorías.” In this interaction, Omar's translanguaging was demonstrated by his fluid and flexible movement from Spanish to English within a statement. First, Omar efficiently read the product information provided in English. Then, he used Spanish (Esta dice) to begin to answer his mother's request; then, he used English to read to her the information (zero calories); and, finally, he went back to using Spanish (no tiene calorías), language brokering (Orellana et al. 2003) to provide her with the translation for meaning‐making purposes. Trusting Omar's translanguaging, Sra. Ortega made the decision to buy the Sweet 'N Low. Through the use of his flexible bilingualism and biliteracy, Omar was able to support his mother with grocery shopping, a common everyday practice.

Korean‐English

The following examples of translanguaging events were derived from Lee's (the third author) study, which was conducted in a first‐grade class at a Korean heritage language school in a university town in the American Midwest. (Pseudonyms are used for all the participants.) The school provides formal instruction in Korean. Yet, since most of the enrolled students were second‐generation Korean‐Americans, Lee, who held positions as an insider (classroom teacher) and an outsider (researcher) in the study, allowed her students to use English and translanguaging in the classroom so that they could utilize their language repertoires from both Korean and English. She, as a bilingual teacher, also used English and translanguaging instinctively and purposefully when she interacted with her bilingual students.

This example shows how a bilingual child demonstrated his sociolinguistic competence by using both languages flexibly through translanguaging. In Excerpt 23.2, Lee asked Joon the name of a game that he was playing during recess. Joon responded in English as the name is originally in English. In responding to Ms. Lee's follow‐up question about how to play the game, Joon provided his answer in Korean but added the English words “go” and “stop” in his Korean speech. The similar pattern was observed in his subsequent utterances. Joon provided English word‐level translanguaging (“two players”) in his Korean speech. To respond to Ms. Lee's question that was asked in Korean, Joon began to speak in Korean (“Because…”) but soon added an English phrase (“I am good at”) to complete his statement, and he continued to insert the English words “stupid” and “really bad” in his Korean speech.

During the interview, Joon revealed that he knew all the corresponding words and phrases in English and Korean. He used the English words because he preferred them, not because he did not know the Korean words. Joon stated, “I prefer speaking in English for some words, such as the words that I often use in English … Sometimes, English words came to my mind first.” The example indicates Joon's flexible use of translanguaging, reflecting his language preference as well as his quicker lexical access to a particular language.

The next example illustrates how Yuna used a translanguaging strategy to conform to a principle of code alignment (Sayer 2011). Excerpt 23.3 shows Yuna considering her interlocutors' language use when she was playing a card game with Hana. While they were using English to play the card game, Ms. Lee interrupted by asking a question in Korean. Yuna answered her teacher in Korean, but when she returned to the game, she talked to her peer in English. Throughout the card game, Yuna conducted translanguaging as she responded to each of the interlocutors in the languages they used; she used Korean to respond to the teacher, but used English to her peer. According to Sayer (2011), bilingual speakers tend to follow the language that the more powerfully positioned speaker uses. Yuna's translanguaging practices indicated that she considered her interlocutors' language preferences and proficiencies as well as the power structures.

Figure 23.2 Translanguaging to ensure the reader's understanding.

Yuna also used translanguaging when writing. Figure 23.2 shows that Yuna composed her diary entry both in Korean and English so that she could convey what she wanted to say to a bilingual reader.

During the interview, Yuna explained that she wrote in English what she had written in Korean to ensure the reader's understanding along with some uncertainty about her Korean proficiency. She explained, “I was not sure about my Korean writing so I rewrite them in English again because I am good at English. And if I make many mistakes in Korean but rewrite them in English again, one (the reader) can know what I write about.” Her repetition of English sentences after writing in Korean is an example of “bilingual echoing” (Gibbons 1987, p. 80). Yuna, who identified herself as English dominant, utilized her linguistic resources to ensure that the reader understood her text.

Implications for research and practice

The literature review and the authors' examples demonstrate that children, youth, and adults are purposeful and intentional in their translanguaging practices within classrooms, homes, and community spaces. Even when translanguaging was not encouraged in the classroom, students navigated school policies for communicative purposes as well as identity development. Our excerpts also demonstrate the fluidity of students' translanguaging practices (they used their “free time” such as the last 10 minutes of the day or recess in formal, educational settings to engage in language learning), thus challenging the dichotomy between formal and informal settings. Given the fluidity of students' multilingual practices across modes (oral, written, digital) and spaces (within and outside formal educational settings), our review suggests that students should be provided with specific opportunities and models for translanguaging in the classroom. Recommendations by García and Wei (2014) at the elementary school level and those provided by Canagarajah (2011a) for college students provide a major starting point for embracing and developing students' multilingual practices. Instructional support within classrooms as well as acknowledgement of students' home and community practices can assist students in understanding the value of using translanguaging across contexts. Aligned with this recommendation is consideration of the distinction between spontaneous and pedagogical translanguaging; while the definitions are helpful in theory, it is likely that they overlap across contexts. A skillful teacher would be intentional about using translanguaging as an approach and would likely encourage spontaneity, modeling for students the use of available linguistic resources. Likewise, a parent might point out the translanguaging practices children are using as they talk, play, or write.

While research conducted in the last 10 years has provided many examples of students' translanguaging practices especially in the school setting, future research should be conducted in more informal settings such as the home and community as well as the spaces students find within formal settings. In particular, documenting children's and adults' practices over time, across contexts, and in various modes (written, oral, digital) could yield valuable insights about translanguaging practices. Of particular interest is understanding how students shuttle among languages with different symbol systems (Arabic, Chinese, Korean, Latin‐based, Germanic, etc.) as they develop their multilingual, multiliterate abilities.

REFERENCES

- Alvarez, S. (2014). Translanguaging Tareas: emergent bilingual youth as language brokers for homework in immigrant families. Language Arts 91 (5): 326–339.

- Alvarez, S. and Alvarez, S.P. (2016). “La Biblioteca es Importante”: a case study of an emergent bilingual public library in the Nuevo U.S. South. Equity & Excellence in Education 49 (4): 403–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2016.1226092.

- Baker, C. (2011). Foundations of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 5e. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

- Bakhtin, M. (1975). Bakhtinian Thought: An Introductory Reader. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Barbour, S. (2002). Language, nationalism, and globalism: educational consequences of changing patterns of language use. In: Beyond boundaries: Language and identity in contemporary Europe (eds. P. Gubbins and M. Holt), 11–18. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

- Bartlett, L. (2007). To seem and to feel: situated identities and literacy practices. Teachers College Record 109 (1): 51–69.

- Bauer, E.B., Vivian Presiado, V., and Colomer, S. (2017). Writing through partnership: fostering translanguaging in children who are emergent bilinguals. Journal of Literacy Research 49 (1): 10–37.

- Becker, A.L. (1991). Language and languaging. Language and Communication 11 (1–2): 33–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/0271‐5309(91)90013‐L.

- Canagarajah, S. (2011a). Translanguaging in the classroom: emerging issues for research and pedagogy. Applied Linguistics Review: 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110239331.1.

- Canagarajah, S. (2011b). Codemeshing in academic writing: identifying teachable strategies of translanguaging. Modern Language Journal 95 (iii): 401–417. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540‐4781.2011.01207.x.

- Cenoz, J. (2017). Translanguaging in school contexts: international perspectives. Journal of Language, Identity & Education 16 (4): 193–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2017.1327816.

- Cenoz, J. and Gorter, D. (2017). Minority languages and sustainable translanguaging: threat or opportunity? Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 38 (10): 901–912. https://doi.org/10.1080/014134632.2017.1284855.

- Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Creese, A. and Blackledge, A. (2010). Translanguaging in the bilingual classroom: a pedagogy for learning and teaching. Modern Language Journal 94 (1): 103–115.

- Creese, A., Blackledge, A., and Hu, R. (2017). Translanguaging and translation: the construction of social difference across city spaces. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualismhttps://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2017.1323445.

- Cummins, J. (1981). The role of primary language development in promoting educational success for language minority students. In: Schooling and Language Minority Students: A Theoretical Framework (ed. California State Department of Education), 3–49. Los Angeles, CA: Evaluation, Dissemination and Assessment Center, California State University.

- Duarte, J. (2016). Translanguaging in mainstream education: a sociocultural approach. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism: 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2016.1231774.

- Durán, L. and Palmer, D. (2014). Pluralist discourses of bilingualism and translanguaging talk in classrooms. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 14: 367–388.

- Edelsky, C. (1986). Writing in a Bilingual Program: Había una vez. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

- Esquinca, A., Araujo, B., and De La Piedra, M.T. (2014). Meaning making and translanguaging in a two‐way dual‐language program on the U.S.‐Mexico border. Bilingual Research Journal 37 (2): 164–181.

- García, O. (2009a). Bilingual Education in the 21st Century. Malden, MA: Wiley‐Blackwell.

- García, O. (2009b). Education, multilingualism and translanguaging in the 21st century (eds. A. Mohanty, M. Panda, R. Phillipson and T. Skutnabb‐Kangas) Multilingual education for social justice: Globalising the local, 128–145. New Delhi, India: Orient Blackswan.

- García, O. and Leiva, C. (2014). Theorizing and enacting translanguaging for social justice. In: Heteroglossia as Practice and Pedagogy (eds. A. Creese and A. Blackledge), 119–216. New York: Springer.

- García, O. and Lin, A.M.Y. (2017). Translanguaging in bilingual education. In: Bilingual and Multilingual Education (eds. O. García, A. Lin and S. May), 1–12. New York: Springer.

- García, O. and Sylvan, C.E. (2011). Pedagogies and practices in multilingual classrooms: singularities in pluralities. The Modern Language Journal 95 (3): 385–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.2011.95.issue‐3.

- García, O. and Wei, L. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism and Education. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- García‐Mateus, S. and Palmer, D. (2017). Translanguaging pedagogies for positive identities in two‐way dual language bilingual education. Journal of Language, Identity, & Education 6 (4): 245–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2017.1329016.

- Garrity, S., Aquino‐Sterling, C.R., and Day, A. (2015). Translanguaging in an infant classroom: using multiple languages to make meaning. International Multilingual Research Journal 9 (3): 177–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/19313152.2015.1048542.

- Gibbons, J. (1987). Code‐Mixing and Code‐Choice: A Hong Kong Case Study. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

- Gort, M. (2012). Evaluation and revision processes of young bilinguals in a dual language program. In: Early Biliteracy Development: Exploring Young Learners' Use of their Linguistic Resources (eds. E.B. Bauer and M. Gort), 90–110. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Gort, M. and Sembiante, S.F. (2015). Navigating hybridized language learning spaces through translanguaging pedagogy: dual language preschool teachers' languaging practices in support of emergent bilingual children's performance of academic discourse. International Multilingual Research Journal 9: 7–25.

- Grosjean, J. (1982). Life with Two Languages: An Introduction to Bilingualism. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Hall, K. (1998). Critical literacies and the case for it in the early years of school. Language, Culture and Curriculum 11 (2): 183–194.

- Heath, S.B. (1983). Ways with Words: Language, Life and Work in Communities and Classrooms. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Hua, Z., Wei, L., and Lyons, A. (2017). Polish shop(ping) as translanguaging space. Social Semiotics 27 (4): 411–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2017.1334390.

- Jonsson, C. (2013). Translanguaging and multilingual literacies: diary‐based case studies of adolescents in an international school. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 2013 (224): 85–117.

- Lanauze, M. and Snow, C. (1989). The relation between first and second language writing skills: evidence from Puerto Rican elementary school children in bilingual programs. Linguistics and Education 1 (4): 323–339.

- Lewis, G., Jones, B., and Baker, C. (2012). Translanguaging: origins and development from school to street and beyond. Educational Research and Evaluation 18 (7): 641–654.

- Li, G. (2006). Biliteracy and trilingual practices in the home context: case studies of Chinese‐Canadian children. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 6 (3): 359–385.

- Lin, A.M.Y. and He, P. (2017). Translanguaging as dynamic activity flows in CLIL classrooms. Journal of Language, Identity & Education 16 (4): 228–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458/2017.1328283.

- MacSwan, J. (2017). A multilingual perspective on translanguaging. American Educational Research Journal 54 (1): 167–201. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831216683935.

- Makelela, L. (2015). Moving out of linguistic boxes: the effects of translanguaging strategies for multilingual classrooms. Language and Education 29 (3): 200–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782/2014.994524.

- Martin–Beltran, M. (2010). The two‐way language bridge: co‐constructing bilingual language learning opportunities. The Modern Language Journal 94 (2): 254–277.

- Martínez, R.,.A., Durán, L., and Hikida, M. (2017). Becoming “Spanish learners”: identity and interaction among multilingual children in a Spanish‐English dual language classroom. International Multilingual Research Journal 11 (3): 167–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/19313152.2017.1330065.

- Maturana, H.R. and Varela, F.J. (1987). The Tree of Knowledge. Boston: Shambhala.

- Orellana, M.F. (2009). Translating Childhoods: Immigrant youth, Language, and Culture. New. Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Orellana, M.F. and García, O. (2014). Conversation currents: language brokering and translanguaging in school. Language Arts 91 (5): 386–392.

- Orellana, M.F., Dorner, L., and Pulido, L. (2001). The work that kids do: Mexican and Central American immigrant children's contributions to households and schools in California. Harvard Educational Review 71: 366–389.

- Orellana, M.F., Reynolds, J., Dorner, L., and Meza, M. (2003). In other words: translating or “Para‐Phrasing” as family literacy practice in immigrant households. Reading Research Quarterly 38: 12–34.

- Palmer, D.K., Martínez, R.A., Mateus, S.G., and Henderson, K. (2014). Reframing the debate on language separation: toward a vision for translanguaging pedagogies in the dual language classroom. The Modern Language Journal 98: 757–772.

- Rogoff, B. (1990). Apprenticeship in Thinking: Cognitive Development in Social Context. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- Rosaldo, R. (1993). Culture and Truth: The Remaking of Social Analysis. Boston, MA: Beacon.

- Saussure, F. (1916). Cours de Linguistic Générale (eds. C. Bally and A. Sechehaye), with the collaboration of A. Riedlinger. Lausanne and Paris: Payot; (trans. W. Baskin, Course in General Linguistics, Glasgow: Fontana/Collins, 1977.

- Sayer, P. (2011). Translanguaging, TexMex, and bilingual pedagogy: emergent bilinguals learning through the vernacular. TESOL Quarterly 47 (1): 63–88.

- Smith, P. and Murillo, L. (2015). Theorizing translanguaging and multilingual literacies through human capital theory. International Multilingual Research Journal 9: 59–73.

- Smith, B.E., Pacheco, M.B., and de Almeida, C.R. (2017). Multimodal codemeshing: bilingual adolescents' processes composing across modes and languages. Journal of Second Language Writing 36: 6–22.

- Song, K. (2016a). Okay, I will say in Korean and then in American: translanguaging practices in bilingual homes. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 16 (1): 84–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798414566705.

- Song, K. (2016b). Nurturing young children's biliteracy development: a Korean family's hybrid literacy practices at home. Language Arts 93 (5): 341.

- Street, B.V. (1984). Literacy in Theory and Practice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Tse, L. (1995). Language brokering among Latino adolescents: prevalence, attitudes, and school performance. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 17: 180–193.

- Velasco, P. and García, O. (2014). Translanguaging and the writing of bilingual learners. Bilingual Research Journal: The Journal of the National Association for Bilingual Education 37 (1): 6–23.

- Volk, D. and de Acosta, M. (2003). Reinventing texts and contexts: syncretic literacy events in young Puerto Rican children's homes. Research in the Teaching of English 38 (1): 8–48.

- Wei, L. (2011). Moment analysis and translanguaging space: discursive construction of identities by Chinese youth in Britain. Journal of Pragmatics 43: 1222–1235.

- Williams, C. (1994). An evaluation of teaching and learning methods in the context of secondary education. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Bangor, Wales.

- Worthy, J. and Rodríguez‐Galindo, A. (2006). ‘Mi Hija Vale dos Personas’: Latino immigrant parents' perspectives about their children's bilingualism. Bilingual Research Journal 30 (2): 579–601.

- Worthy, J., Durán, L., Hikida, M. et al. (2013). Spaces for dynamic bilingualism in read‐aloud discussions: developing and strengthening bilingual and academic skills. Bilingual Research Journal 36 (3): 311–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/15235882.2013.845622.