Chapter Seven

THE NEW ORDINARY

Before McDonald’s, the world’s first fast-food chain was White Castle. In Kansas in 1916, cook Walter Anderson set up a hamburger stand and invented a new way of serving hamburgers (making the patties thinner, putting onions on top). The trouble was, burgers were not popular due to health concerns—burgers at the time were mostly sold at lunch wagons and carnivals, with low-quality meat and poor hygiene.1 Anderson had imagined and created a new hamburger, but to realize its potential, he needed to create the systems and processes to make take-out, fast-food hamburgers a new normal for millions of people.

Anderson met a business partner, Billy Ingram, a real estate and insurance agent, who envisaged a corporate empire with multiple interlocking businesses built around the new burger. In 1921, they set out to create this business, renaming their company White Castle System, Inc. (See figure 7-1.)

Figure 7-1 Walt Anderson and Billy Ingram were the founders of the White Castle System®, the first fast-food chain

Source: © White Castle®. Reproduced by permission.

The White Castle System was a script—a set of instructions, articulated in manuals, booklets, posters, training programs, advertisements, and personal communications—to shape the thoughts and actions of many people in different roles, most of whom were not involved in the development of the original idea, many of whom Anderson and Ingram would never even meet. As the Kansas Historical Society notes: “White Castle proved successful because the company developed standards of operation. Anderson created paper hats, paper wrapped hamburgers, a manual for food preparation, and guidelines for employee cleanliness and appearance.”2 (See figure 7-2.)

Figure 7-2 A White Castle® interior, 1947

Source: © White Castle®. Reproduced by permission.

Chapter Overview

The challenge of reshaping reality

How to write evolvable scripts

UNDERSTAND

- Reflect after success

- Identify the essence

ARTICULATE

- Clarify the purpose

- Focus script on action

- Deploy realists

EVOLVE

- Allow discretion

- Evolve existing scripts

- Erase scripts

Blocks to evolvable scripts

BEING EXCESSIVELY PROCEDURAL

BEING OVERLY PRODUCER FOCUSED

DESIRE FOR CONTROL

TRYING TO BE COMPLETELY “MECE”

Games to play

THE NO-FRICTION GAME

THE CODIFICATION GAME

Good questions to ask

Organizational diagnostic

The system included a number of elements: a simple menu, cheap pricing strategy, intense marketing, as well as a standardized cooking process, uniform codes, and regularly cleaned, enamel buildings.3 No one had built a fast-food chain before, so the infrastructure didn’t exist. Anderson and Ingram created what we would today call a business ecosystem; they built meat supply plants, bakeries, and two supporting businesses: Paperlynen, to make paper products for the restaurants, and Porcelain Steel Buildings, to make their unique prefabricated porcelain walls. By 1931, White Castle had 131 outlets; in 1961, it became the first restaurant to sell one billion burgers; today it continues, a hundred years after founding.4 (See figure 7-3.) Although the business was eventually overtaken in size by others, it shaped an entire industry.

Figure 7-3 White Castle®, 2020

Source: Universal Images Group North America LLC/Alamy Stock Photo.

White Castle’s growth illustrates that if you want to harness collective imagination, you need to turn your imaginative mental model into a new normal, which for an existing company involves a wholesale transformation. This chapter will explore the idea of an evolvable script as the means for doing this, best practices for creating such scripts, blocks to doing so, productive games to play, questions to ask, and an organizational diagnostic.

The Challenge of Reshaping Reality

How can you shape a new reality? When we think about corporations, we tend to focus on the material aspects—the products, warehouses, shop fronts, labs, impressive headquarters, and so on. But as we touched on in chapter 4, businesses are predicated on mental models. For example, LEGO, at one point, was not a thing, and now it is, not only because some factories have manufactured colored bricks. If you gave some LEGO bricks to a cave man in 30,000 BC, he wouldn’t know what to do with them. LEGO products shaped the world because the LEGO Group created a script that shaped the minds of the people making up the company and its customers. The mental side of the product has been articulated and spread; there is a widely understood mental model of what these colored objects are and how to use them, all organized under a now-familiar name, LEGO, which at one point in history meant nothing.

What’s extraordinary about corporations is that they come from the mind but have a massive power to reshape reality. A rough estimate of the total weight of all iPhones ever made is 374 million kilograms (2.2 billion phones at an average of 170 grams each): raw materials that have been excavated, transformed, and sent around the world in people’s pockets. Even the sternest critics of corporations, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, were not able to resist a sense of awe:

The bourgeoisie, during its rule of scarce one hundred years, has created more massive and more colossal productive forces than have all preceding generations together. Subjection of Nature’s forces to man, machinery, application of chemistry to industry and agriculture, steam-navigation, railways, electric telegraphs, clearing of whole continents for cultivation, canalization of rivers, whole populations conjured out of the ground—what earlier century had even a presentment that such productive forces slumbered in the lap of social labor?5

It is easy to let the power of such corporations—Apple, Samsung, GE, Exxon Mobil, Nike, or others—lead us to believe that their identity and their power derive from material things. Yet a company does not even have the material solidity of a simple object, like a shoe. If you take a shoe off, you can put it in the corner, and it will stay that way until it slowly degrades and, eventually, returns to dust. A company’s essence is not tied to matter: it is a set of interrelated mental models in people’s brains, shaped by a corporate script. A company would evaporate within days if people no longer wanted or needed to play their roles within it.

At the heart of the corporation is a mental operating system that holds everything together: a script that can be articulated in rules and processes and strategy, but that is run on people’s brains. Writing and enacting such a script is how we reshape reality. When a script is running, it creates an institution, a corporation that orchestrates large amounts of resources and makes new mental models and actions familiar, so eventually they become the fabric of a new reality. Eventually, the White Castle System created a new ordinary in which millions of people buy burgers—from ubiquitous outlets supported by large supply chains—assuming without question that the food will be safe and tasty.

How can we learn to do this well? How can we turn our imagined mental model into the basis of a new everyday reality?

How to Write Evolvable Scripts

We might see policies and procedures as the end, even the antithesis, of imagination. But institutionalizing an idea is in fact a different type of imaginative challenge because we have to use counterfactual thinking to picture the new reality and the corporate machine that will bring it about. The White Castle System was an extraordinary achievement of grounded counterfactual thinking: a script for a never-before-seen kind of business, which was clear enough to guide others and actually worked in practice.

By corporate script, we mean any kind of guidance that drives thought and action. For example, let’s say you are running a movie theater company, and you reimagine the mental model for how a theater should run. Following this, you need to write the script for the new theaters and supplemental services—guidance and instruction you will communicate to the franchisees, customers, and vendors who will create and live within the new normal.

There are three steps to creating and running an effective corporate script: understand, articulate, and evolve.

Understand

First, we need to grasp the essential value of the imaginative idea we have created—the key ingredients and causal relationships, and what is merely incidental. This is the essential value we want to capture and codify in the script.

REFLECT AFTER SUCCESS

Usually when something doesn’t work, we spend time figuring out what happened. But avoiding failure is not success. And success does not automatically mean repeated success. In fact, succeeding is usually more complex and mysterious than failing, as it involves a system of successful interactions, whereas failure usually involves one or a few things going wrong.

Losers in a competition often take a break to enter a period of soul searching. Ideally, success should also trigger reflection and soul searching, as this is the best time to reverse-engineer why something worked so it can be replicated.

At the BCG Henderson Institute, we ring a bell after any major success. The bell signals the need not only to celebrate but also to pause and reflect, to codify what went right (see figure 7-4). The team then meets to explore everything that led to the moment of success and capture this in our recipe book (simple, evolvable scripts) for important routines, such as how we research and develop a new idea. A similar policy could be adopted in any business as a starting point for codifying new scripts.

Figure 7-4 The bell to ring to discuss what led to success

Source: Jack Fuller, photographer, 2019. Courtesy of the BCG Henderson Institute. All rights reserved.

IDENTIFY THE ESSENCE

Once we have made time to reflect after success, a key action is to identify the essence of why something worked. For example, in the late 1990s, Adidas explored the idea of personalizing footwear. The team harnessed imagination effectively: they rethought the experience of buying a shoe, tried this out, rethought, and did further pilots. Then, they drilled down to identify the essence of what was successful in these tests. They discovered that consumers were more concerned about customized fit than customized design, something they hadn’t expected. This was the starting point for writing a new organizational script, which Adidas eventually enacted to transform thousands of stores.6

Not usually considered a time for soul-searching. Source: PA Images/Alamy Stock Photo.

An imaginative, thoughtful team, after a success—thinking hard about what went right. Source: Claudio Villa/Getty Images Sport via Getty Images.

Another example of extracting essential principles of success comes from educator Maria Montessori. Early in the twentieth century, she turned her ideas about education from one-off successes into a script that others could follow. As director of a school in Rome, she noticed one child who was having difficulty learning how to sew. She tried a few things out and discovered that the girl, while she struggled with sewing, enjoyed weaving pieces of paper together.7 Montessori focused on the task the student enjoyed. Later, the girl picked up sewing. This was an imaginative success for Montessori. But it became more than a one-off success because she mined such encounters for essential principles (see figure 7-5).

Figure 7-5 The seven Montessori principles

From this small success, she drew a key insight: “We should really find the way to teach the child how, before making her execute a task … by means of repeated exercises not in the work itself but in that which prepares for it.”8 This became the principle of a “prepared environment” in the overall script: the Montessori Method. This method made the difference between one school in Rome shaped by reimagination and a scalable script, now followed by around twenty thousand schools around the world—the most widespread method in education.9

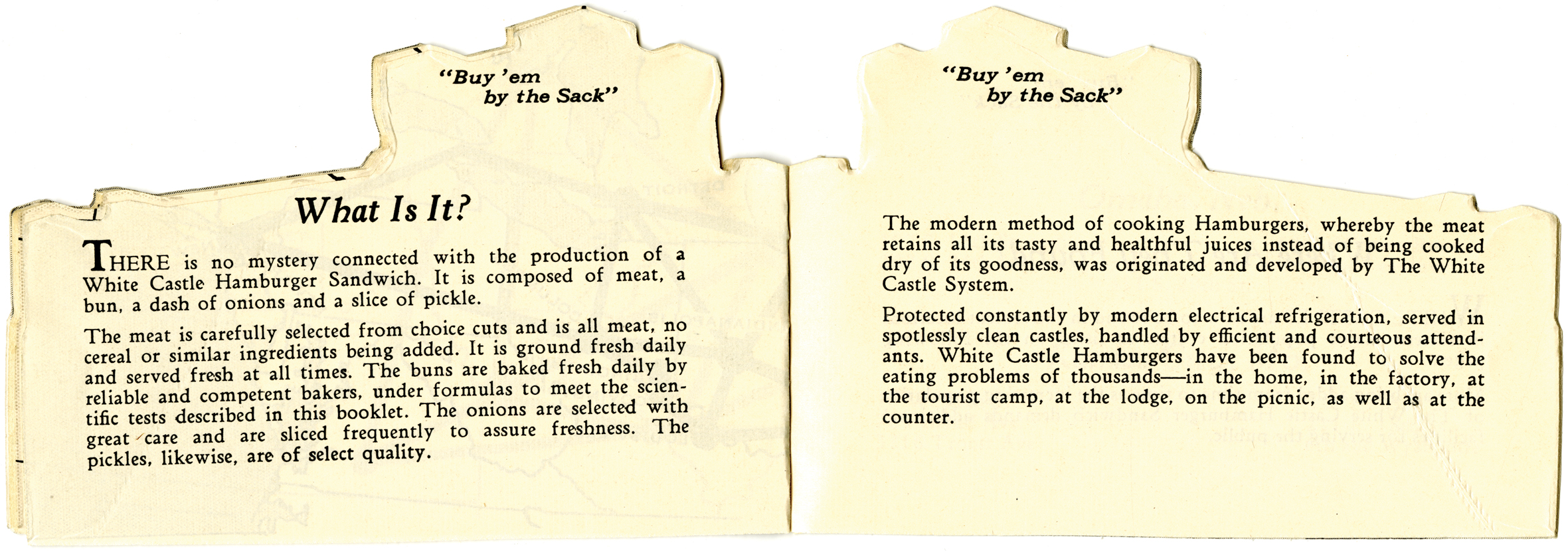

To take another example, when Ingram examined Anderson’s successful hamburger stand, he noticed that one essential element was the cleanliness. They enshrined this in the White Castle System, communicated to employees on posters in every outlet (see figure 7-6).

Figure 7-6 Essential to the White Castle® corporate recipe: hygiene and a clean appearance

White Castle® appearance chart, 1956. Source: © White Castle®. Reproduced by permission.

This element of the script also shaped their communications with customers, in castle-shaped booklets, emphasizing that the food is “protected constantly by modern electrical refrigeration, served in spotlessly clean castles” (see figure 7-7).

To others in the mass-market food industry of that day, focusing on cleanliness would not have seemed obvious or essential. Customers didn’t expect it; most cooks and owners probably saw their role as just serving the food, perhaps chatting with patrons. The clarity, confidence, and independence of mind to highlight and focus on this laid the groundwork for a successful corporate script that would transform the entire industry.

Figure 7-7 Shaping the mental models of customers

White Castle® brochure, 1932. Source: © White Castle®. Reproduced by permission.

To distinguish the essential from the incidental, we should focus on elements that are:

- Critical to success

- Nonobvious

- Difficult; that is, which require an explicit script

- Differentiated from similar things in the world

- Generative; that is, if you get this one thing right, many other good things will likely follow

Articulate

Once we have understood what is essential to the success of a newly imagined idea, we need to articulate these elements in a corporate script: the more- or less-specific guidance required so that people who have no knowledge of or experience with the mental model, and may not be immediately inspired by it, are able to play their part in realizing it. (See the sidebar “Elements of Corporate Scripts.”)

CLARIFY THE PURPOSE

In order to frame the specifics of who does what, you must first specify your purpose. A purpose is a kind of goal—a description of what you hope to bring about. It is the goal for the overall effort. To describe the purpose, identify the intersection of your:

- Aspirations: the exciting possibility you have envisaged with your mental model

- Capabilities: what is possible given the resources you might access now and in the future

- Context: the jobs to be done within the broader system of which you are a part

A key function of a purpose is to stop people blindly pursuing some tactical part of the script while losing sight of the intention of the whole. In his 2016 letter to shareholders, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos wrote that leaders must “resist proxies,” meaning “the process is not the thing.”10 A proxy is an intermediate goal, like “reduce maintenance costs” in an industrial equipment company, on which you can end up focusing a lot effort, but which is not the overall goal. The danger with proxies is that you end up skewing the collective effort, if from your perspective, for example, it becomes irrelevant whether customers hire your equipment or whether you have any inventory.*

What are the different elements that you can put into a corporate or institution-building script? The elements are different kinds of guidance to shape people’s mental models and actions (communicated via manuals, presentations, training sessions, implicit instructions built into design, marketing materials, personal discussions, and so on) that result in the creation of a new reality.

We can picture the possible elements for a script as parts of a house. At the top is a purpose. This overall goal connects a business to the social system it is embedded in by delineating some useful contribution to individual or collective flourishing, orienting the entire business and serving as an aspiration for future growth. For example, a reimagined bank could have as a purpose to help us be happier and wiser about money across all the ways money impacts our lives.

Under the purpose is strategy, which is everything it takes to win competitively, in pursuit of the purpose, and goals and metrics, which specify targets within the strategy and enable us to assess progress.

Under this are a range of possible elements we can add into scripts that specify how this purpose will be achieved in detail:

- Principles: Key pieces of guidance that can be applied in many situations. For example, “customer-facing staff in the hotel should use their discretion when they can see a way to solve a guest’s problem.”

- Rules: Descriptions of specific behaviors to enact or avoid. For example, “clean the restaurant every two hours.”

- Protocols: Codes of conduct comprising principles and rules. The term “protocol” comes from diplomacy; for example: “the following twenty-five rules and six principles should be followed in order to orchestrate a state dinner.” In business, we might have protocols for running an investor call, engaging a new customer, conducting a recruiting interview, and so on.

- Processes: Series of actions intended to produce particular results or kinds of results. For example: the sequence of steps for cooking a beef patty, assembling a car, analyzing customer metrics, or testing a new drug.

- Role descriptions: Priorities and responsibilities of personal roles. For example, “this reimagined real estate company depends on estate agents with the skills to handle the following responsibilities: emotional engagement with the client, design advice, and help with financial planning.”

Within each of these ways of giving guidance lie critical details vital to success. For example, the exact length of time to cook a burger, the ideal temperature of a store during shopping hours, the minimum inventory levels for a factory, the need for all toys to be intercompatible, or the threshold for the efficacy of a drug.

Finally, one important aspect of the script is its evolvability. This is the capacity for the script to adapt in response to change and surprise. We will explore the theme of evolvability later in the chapter.

Possible elements of corporate scripts

FOCUS SCRIPT ON ACTION

When articulating elements of the script that will guide people to shape the new reality, it is tempting to focus on description, explanation, or justification. But whether you are communicating it through a corporate manual, onboarding training, or personal communication, every piece of the script should be oriented around prompting and guiding action.

To see what makes a good script, imagine three different sports coaches, each trying to train beginner athletes to jump over a vaulting horse.

How do you write a script for doing this? Source: Nationaal Archief (Dutch National Archives), via Creative Commons. Photograph by Sterling/Anefo.

- The first coach tells students to “optimize your velocity and angle of attack relative to the height of the object.” (He continues with a lecture about mass and momentum.)

- The second coach says simply, “Empty your mind.”

- The third coach tells students to “lean against the edge of your chair and push the weight of your body up and down with your arms and remember this sensation as you run up to the vaulting horse.”

Which coach is likely to be the most effective? The first is technically correct, but his instructions were too complicated to guide action in real time. This often happens in corporate scriptwriting. In one BCG project, we worked on an operational assessment of a pharmaceutical company. The company had hundreds of pages of procedures and protocols for managing safety—in theory, the script for how the machine of the company should run in enormous detail. But no one understood it because it was too much for anyone to even read.

The second coach’s recipe is indeed simple—“empty your mind”—but useless for instructing people who are not already trained athletes. The business equivalent might be a vice president asking their CEO, “How should I scale up this program to a thousand stores across Latin America?” and getting the answer, “Just go for it. Be bold. Believe in yourself.”

The third coach’s recipe is what we should be aiming for. She figured out the essential actions that mattered most—the muscle movements really are the key to vaulting—and described it in a way that anyone could follow.

A great example of memorable, action-oriented code is Apple’s rules for store employees: Approach, Probe, Present, Listen, End:

- Approach customers with a personalized warm welcome.

- Probe politely to understand all the customer’s needs.

- Present a solution for the customer to take home today.

- Listen for and resolve any issues or concerns.

- End with a fond farewell and an invitation to return.

This beautifully simple code is written to be comprehended and used. Within Apple stores, it is called the “credo,” and employees meet daily to discuss one of the five steps and share examples with the team.11

Complex sets of rules don’t transmit information effectively, and people do not understand or use them. When scriptwriting, we should think like a sports coach at half-time: we have a few minutes of others’ attention to use words and diagrams to guide observation, thought, and behavior.

DEPLOY REALISTS

In articulating a script, one valuable move is to involve people who can think pragmatically about how something might work and what could go wrong. Investor Bill Janeway emphasizes the value of grounded imagination: “I think of imagination as constructive and productive when it is grounded in a multidimensional appreciation of where we are and therefore from where we’re beginning.”12

People who think of themselves as imaginative and those who think of themselves as realists don’t usually work well together. But one way to think about realists is that they are people with a particular bent to their imagination: because of their awareness of the complexity of reality, their counterfactual thinking focuses on the challenges of implementation. Imagination is a calibrated departure from the current mental model of reality: too realistic and there is no innovation; too unrealistic and it becomes an impractical fantasy. The ideal calibration varies according to the maturity of the mental model. Deploying realists too early can suppress idea development. Deploying them at the point of codifying a corporate script can be productive. In the Adidas example of personalized footwear, such a person’s mind might jump to:

- The difficulty of working with retail partners around the world, given differing expectations about who will pay for the new equipment

- The challenge of fitting customization into Adidas’s existing departments; thus the need to rethink Adidas’s structure as part of codifying this program

- The difficulty of doing customized manufacturing in Adidas’s existing factories

Involving minds focused on the trickiness of current reality will help articulate a script for thought and action that will effectively reshape reality.

Evolve

An overall consideration in writing a corporate script is to design it so that it can evolve, to change in response to changing demands or opportunities.

ALLOW DISCRETION

One way to enhance evolvability is to allow for individual discretion. Institutional scripts always have the potential to turn people into (unintelligent) robots: when they interpret the code as “follow these instructions and do not think.” Instead, a corporate code should make room for and draw on the imaginations of the people enacting it.

As we noted in the previous chapter, online retail company Zappos does this effectively. The script that drives the company is called “Holocracy” and involves largely autonomous teams that function like startups.13 Employees can join or leave teams at will, and teams and individuals can write new corporate script. As founder Tony Hsieh said to us, “If an employee wants to start up a circle to set up a cupcake bakery, that would be great. The only demand is that this bakery abides by our purpose to deliver the very best customer service, customer experience, and company culture.”14

Figure 7-8 Zappos’s Triangle of Accountability

Source: Courtesy of Zappos.

This level of discretion is balanced by an additional key piece of corporate script: the Triangle of Accountability, which codifies criteria by which each team must guide itself. (See figure 7-8.)

Another example of creating room for discretion is the Four Seasons hotel chain. When building the global corporate machine in the 1980s, founder Isadore Sharp faced a challenge of corporate scriptwriting: how to identify the essence of his early hotels and build on it to create a global chain based around core, shared mental models. Sharp believed that frontline employees were key to the hotel experience. He wanted to invest enough in training and supporting frontline staff to justify trusting them to improvise or bend rules to solve customer problems. Sharp wrote a credo articulating this: “It took most of the first half of the 1980s to clear out all the obstacles that stood in the way of improving service: to part ways with every executive who believed my ‘kooky’ credo should be confined to the PR department, to part ways with every executive whose actions contradicted policy.”15

Sharp’s policy, a key piece of the corporate script, now underpins the operations of over a hundred hotels worldwide. One employee noted how the principles shaped the reality: “I have countless stories about how this philosophy played out. A bartender once sent me to a corner bar to pick up a six-pack of Rolling Rock even though it wasn’t on our beer menu. I knew a doorman who jumped in a cab to return a lost teddy bear to a kid at the airport. People spoke of the Room Service waiter who borrowed blueberries from another hotel at 3 a.m. because we ran out.”16

You should include enough room for discretion in your institutional recipe so the imaginations of the people involved aren’t underutilized.

EVOLVE EXISTING SCRIPTS

Another challenge is not just to evolve the script you are newly writing but other preexisting scripts to which it relates. When you are transforming a company or designing a new department around a new product, a new script often runs up against established ones.

Media entrepreneur John Battelle has an example of this challenge from the perspective of an outsider. Battelle had thought of a new business model, and he wanted to partner with a large company. He approached the company, and even though it saw the merit in his idea, the company was unable to transform its existing protocols to do anything about it:

We approached the company with our business idea: we wanted to get access to some of their discarded product. We said: “We want to give you a piece of our equity for the rights to this stuff you are discarding. You don’t have to do anything for it. In fact, our venture will probably help increase your customer base. It is free for you. How could you say no to this?”

So of course, they took the meetings, they got excited. But then they threw it over to their legal department, and the CFO’s office, because legal has to approve any deals. That’s where it hit the rocks. They did not know how to do it, within their protocols. They even admitted this to us in the room. They said: “This is a great idea. But we don’t know how to do a deal where we own a minority stake in a company. Give us something we’re used to doing.”17

The company was unable to make room within its established script—its existing operating system—for an imaginative, valuable new effort.

White Castle® challenging its own script. Source: Courtesy of Miso Robotics.

In another example, White Castle has recently begun to experiment with using AI-driven robots in its kitchens, a move that has the potential to disrupt its existing corporate script.

This effort is currently at the formative stages of imagination: collective imagination and experimentation. But it could become the basis for envisaging a wholly new script for White Castle, part of which (written in actual computer code) is run on robot arms in the kitchens, with the human scripts (written into training programs and key principles) guiding employees around customer engagement. Anderson and Ingram’s White Castle System from 1921 would have to evolve, merging with new, AI-augmented scripts, leading, once everything becomes familiar and habitual, to a “new ordinary.”

A new corporate script: White Castle® in collaboration with Miso Robotics. Source: Courtesy of Miso Robotics.

An established script is the operating system, the software, on which the company runs. This software must be updatable. As well as imagining new script, we should be ready to evolve the old.

ERASE SCRIPTS

One ongoing and often neglected task in any corporate system is to trim rules and protocols to contain complexity within a tractable range.18 For example, Netflix has a rule to eliminate unnecessary rules: “As we grow, minimize rules.”19 CEO Reed Hastings and chief talent officer Patty McCord codified their approach in a slide deck on best practices for Human Resources, which Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg has called “one of the most important documents ever to come out of Silicon Valley.”20 A key principle it emphasizes is to “eliminate distracting complexity (barnacles)” and “value simplicity.” The document discusses “rule creep”: “ ‘Bad’ processes tend to creep in—preventing errors just sounds so good. We try to get rid of rules where we can, to reinforce the point.”21

Trader Joe’s also has an effective script erasure process: keeping its total number of products stable by removing the old as it introduces the new. In this way, there are never so many products that workers don’t know enough about each one to be able to discuss it with customers.

Erasing script comes from seeing the whole. Even if a particular rule might be justified by some local need, we should never forget to weigh this against the need for the company script as a whole to function—to remain understandable and evolvable.

Blocks to Evolvable Scripts

There are a number of commonly encountered obstacles to imagining and enacting evolvable corporate scripts, especially when the starting point is within an existing large business.

Being Excessively Procedural

This is the habit of thinking only according to tightly defined procedures, preventing evolvability. This pathology can develop from the fear of punishment for doing something wrong, or an excessive attachment to clarity and an aversion to ambiguity. The antidotes are to reinforce the purpose as the true goal, rather than the procedures, and to support people in going off-script when they think it makes sense, despite missteps that may occur.

Being Overly Producer Focused

This is the tendency to forget that the point is to create value for the customer and so forgetting to design based on the customer’s experience. It gives rise to rules and procedures that make sense from a partial, internal perspective (someone in procurement or the finance team) but that neglect the customer, and so stop the script from being effective for customers, whose lives it is designed to make better. The solution: regularly talk to customers, go through the process from their perspective, and rewrite the corporate script as required.

Philosophies of Instruction

A script is a means of instructing or guiding people. All scripts should be evolvable, to some degree, and all scripts should specify something to be done. Evolvability is the degree to which the script itself changes, is erased, or is added to over time. Specificity is the degree to which the script tightly defines actions, versus leaving room for interpretation and imagination. The two are linked: writing a script that leaves lots of room for discretion helps prompt the imagination that may help the script evolve more over time. But there are a number of possible approaches along these dimensions.

What factors drive the choice of approach? Evolvability versus rigidity depends on how likely the value proposition is to change over time. In business environments that are unpredictable or newly emerging, it makes sense to make corporate scripts that are designed to change. The scripts’ specificity versus generality depend on the degree to which people’s imagination is required to realize the value proposition and on how critical the precise details are to success. To ensure consistency of customer experience across a franchise business or in relation to safety rules, it makes sense to be very specific. When people need to improvise or customize to create value because customer needs are varied or subtle, it makes sense for scripts to be more general.

Let’s look at some examples. You might create a script that specifies in detail the required ways of thinking and behaving, not designed to evolve much over time, such as the original White Castle System. When Four Seasons founder Isadore Sharp spent a day sitting in on a McDonald’s training session in the 1960s (he admired McDonald’s and was trying to learn lessons from its script), he noted that the materials were fifteen to twenty years old. “It struck me then that when you have something people can identify with, you don’t have to keep reinventing it; once it’s rooted, it sticks.”a McDonald’s bets on the fact that people will want cheeseburgers for a long time. And it requires accuracy, not imagination, to make one. The best script elements to employ in this case are rules, protocols, and detailed role descriptions.

Trade-offs in corporate scriptwriting

Alternately, you might write an institution-building script with more general guidance, but still relatively rigid. Examples include Montessori’s method: the core principles of how to educate a human being are intended to remain the bedrock, but these can be interpreted imaginatively by teachers in different circumstances. Apple’s script for its retail stores is another example. The stores have a credo of general but largely unchanging principles. Good in-person retail service is a pretty permanent value proposition, but which requires latitude for on-the-ground interpretation by employees. Principles are the go-to element in this kind of script, as well as key metrics, all linked to an overall purpose. A good way of communicating these is via observation and mentorship, to learn how the principles can play out in different circumstances.

Another approach to scriptwriting is to create a general and evolvable script. Zappos, for example, specifies very little, other than to be nice to customers, follow the company culture, and balance your P&L. Everything else changes, and even this high-level script is intended to evolve as the company and the meaning of an excellent customer experience evolves. This allows Zappos to define and pursue new value propositions, drawing on the imagination of staff members as they go. The script behind some of Apple’s products (as opposed to its stores) also embodies this logic. The ecosystem of iPhone, App Store, developer, and customer is built from processes and protocols that are designed to evolve as new needs and apps emerge. The best way to communicate a script like this is by clearly setting the purpose and being specific about some core aspects of how the platform works (listing, pricing, profit sharing, branding, and the like) but letting market principles play out for the assortment of apps.

Finally, a script can also combine specificity and evolvability. One example is Netflix, which operates in a fast-changing industry, but which still needs to define specific guidance across its business units to deliver on its (evolving) value proposition. Its solution has been to enshrine a specific rule for removing rules. To create this kind of script, you can draw on all the elements, from purpose to processes to specific rules. Evolvability depends on constantly revisiting the script.

NOTE

a. Isadore Sharp, Four Seasons (New York: Penguin Publishing Group, 2009), 92. For the date of this anecdote, see: Sheridan Prasso, “Four Season’s Recession-Proof Philosophy,” CNN Money, May 7, 2009, https://

Desire for Control

This is the temptation to imagine that we can specify everything in advance. It often derives from a worry about what might ensue if there aren’t enough rules, without actually testing out this possibility. The anxiety can become the driver of rulemaking rather than the goal of creating something valuable. One countermeasure is to track the adoption and usefulness of the rules in practice and to trim unnecessary complexity. One can also experiment to see if more easily understood and more flexible principle-based guidance give superior outcomes to explicit and complex rules.

Trying to Be Completely “MECE”

This pathology is the belief that every list, document, and set of principles must be mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive (MECE), leading to an uncontrolled blooming of specifications, descriptions, and rules for contingencies. The antidote is to remember that, while the principle MECE has its applications, the point of a script is not to be exhaustive; it is to be communicable and usable, even enjoyable to read or communicate, to prompt the few actions that matter most, rather than covering every eventuality.

Games to Play

The No-Friction Game

Imagine a business like yours but one where customers experience no friction: perfect choice, perfect information, no search costs, perfect understanding of your offering, perfect availability, no mistakes, no quality issues or rework, and no delays. Then observe where your actual business departs from this ideal scenario. Consider the cost of the current frictions. Then ask yourself: What sources of friction are largest and most tractable to eliminate or substantially reduce?

If you have a script for how you will scale up and deliver a new imaginative idea, consider it in this context: How will this new corporate script help address the existing sources of friction? Or if you don’t, think about what sort of script could bring about such a reduction in friction.

Of course, no business is friction-free. But disruptors, to have a viable and compelling proposition, will necessarily address a source of friction that incumbents take for granted. It can be hard to identify such frictions since the current business model may have decades of precedent and seem reasonable or unavoidable. There may be no customers complaining about or competitors yet addressing these frictions. You might imagine a friction-free insurance company, for example. Comparing your current company to this ideal, you could ask: Is it inevitable that there are many risks that are hard to insure, that insurance contracts are hard to understand, that it’s hard for individuals to comprehend their total risk profile, that it’s painful to adjust one’s insurance portfolio, that intermediaries take substantial margins for providing navigation and advice, and that claims are resolved only after a substantial delay? As you write a transformational script for your company, you can be guided by reducing such frustrations. Addressing frictions generally involves not only adding novelty but eliminating complexity in the existing scripts that guide your business.

The Codification Game

The task of translating an imagined new thing into a script that will guide others to realize that new thing is a difficult one. To practice this on a small scale with colleagues, make some object, like a castle, out of LEGO bricks. When you have finished, don’t show this object to the others. Instead, in words, describe the object and how others should recreate it (the script). Their task is then to build that object out of LEGO bricks, based only on the script.

To take the game to another level, different teams can compete with different scriptwriting philosophies. One team could specify every action with detailed rules. Another could describe the core principles only. And another could focus on communicating just the overall purpose or outcome. You can also change the objective from the most accurate reproduction to the fastest adequate model to the most interesting model to the one that is the most fun to make, and so on.

You can extract lessons about how different scriptwriting approaches and behavioral biases can help or hinder the translation of an idea into reality. You can then apply these lessons to transforming part or all of your existing corporate script in light of a promising, imaginative idea.

Good Questions to Ask

Some good questions to ask in writing the script that will scale your imaginative efforts are:

- What’s the minimum someone would need to know to execute and deliver the new idea successfully?

- What is the purpose of this set of procedures?

- Where do people need to use discretion within this script?

- What customer experience are the procedures designed to deliver?

- In addition to writing, how will we deliver the script and reinforce it to those using it?

- Is the trade-off between completeness and comprehensibility optimal?

Organizational Diagnostic

You can apply this diagnostic to your organization to get a sense of how effectively you create and manage corporate scripts. Each question is linked to a related action in this chapter that you can turn to if you need to work on that area.

Never |

Rarely or less than once a year |

Sometimes or once a month to once a year |

Usually or once a week to once a month |

Always or more often than weekly |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

||

Related action |

||||||

Employees take time after successes to reflect on why that outcome happened. |

Reflect after success |

|||||

The firm translates one-off successes into general principles or rules to follow. |

Identify the essence |

|||||

Our company’s purpose statement is useful and provokes imagination. |

Clarify the purpose |

|||||

A typical employee knows and uses our corporate principles and institutional knowledge. |

Focus script on action |

|||||

In general, individual employees in our firm balance visionary and realist tendencies. |

Deploy realists |

|||||

Our corporate codes allow for individual discretion. |

Allow discretion |

|||||

Our firm has an explicit process that it regularly uses for removing unnecessary rules. |

Erase script |

|||||

TOTAL |

After you have added up your total, score your current situation: 31–35, excellent; 21–30, good; 11–20, moderate; 0–10, poor. To benchmark your score against other organizations, please visit www

* Examples from machine intelligence illustrate this at an extreme level because AI is good at goals that are tied to a particular task but not good at interpreting overall statements of purpose. In the book Superintelligence, philosopher Nick Bostrom gives an imaginary example of a hyperintelligent computer that is given the goal “make paper clips” and ends up using every possible resource toward that end, eventually consuming the Earth, then turning large portions of the universe into paper clips.