This chapter will outline the viewpoints that will be set forth in the remainder of the book. In particular we wish to develop at the outset our concept of appropriate portfolio policy for the individual, nonprofessional investor.

Investment versus Speculation

What do we mean by “investor”? Throughout this book the term will be used in contradistinction to “speculator.” As far back as 1934, in our textbook Security Analysis,1 we attempted a precise formulation of the difference between the two, as follows: “An investment operation is one which, upon thorough analysis promises safety of principal and an adequate return. Operations not meeting these requirements are speculative.”

While we have clung tenaciously to this definition over the ensuing 38 years, it is worthwhile noting the radical changes that have occurred in the use of the term “investor” during this period. After the great market decline of 1929–1932 all common stocks were widely regarded as speculative by nature. (A leading authority stated flatly that only bonds could be bought for investment.2) Thus we had then to defend our definition against the charge that it gave too wide scope to the concept of investment.

Now our concern is of the opposite sort. We must prevent our readers from accepting the common jargon which applies the term “investor” to anybody and everybody in the stock market. In our last edition we cited the following headline of a front-page article of our leading financial journal in June 1962:

SMALL INVESTORS BEARISH, THEY ARE SELLING ODD-LOTS SHORT

In October 1970 the same journal had an editorial critical of what it called “reckless investors,” who this time were rushing in on the buying side.

These quotations well illustrate the confusion that has been dominant for many years in the use of the words investment and speculation. Think of our suggested definition of investment given above, and compare it with the sale of a few shares of stock by an inexperienced member of the public, who does not even own what he is selling, and has some largely emotional conviction that he will be able to buy them back at a much lower price. (It is not irrelevant to point out that when the 1962 article appeared the market had already experienced a decline of major size, and was now getting ready for an even greater upswing. It was about as poor a time as possible for selling short.) In a more general sense, the later-used phrase “reckless investors” could be regarded as a laughable contradiction in terms—something like “spendthrift misers”—were this misuse of language not so mischievous.

The newspaper employed the word “investor” in these instances because, in the easy language of Wall Street, everyone who buys or sells a security has become an investor, regardless of what he buys, or for what purpose, or at what price, or whether for cash or on margin. Compare this with the attitude of the public toward common stocks in 1948, when over 90% of those queried expressed themselves as opposed to the purchase of common stocks.3 About half gave as their reason “not safe, a gamble,” and about half, the reason “not familiar with.”* It is indeed ironical (though not surprising) that common-stock purchases of all kinds were quite generally regarded as highly speculative or risky at a time when they were selling on a most attractive basis, and due soon to begin their greatest advance in history; conversely the very fact they had advanced to what were undoubtedly dangerous levels as judged by past experience later transformed them into “investments,” and the entire stock-buying public into “investors.”

The distinction between investment and speculation in common stocks has always been a useful one and its disappearance is a cause for concern. We have often said that Wall Street as an institution would be well advised to reinstate this distinction and to emphasize it in all its dealings with the public. Otherwise the stock exchanges may some day be blamed for heavy speculative losses, which those who suffered them had not been properly warned against. Ironically, once more, much of the recent financial embarrassment of some stock-exchange firms seems to have come from the inclusion of speculative common stocks in their own capital funds. We trust that the reader of this book will gain a reasonably clear idea of the risks that are inherent in common-stock commitments—risks which are inseparable from the opportunities of profit that they offer, and both of which must be allowed for in the investor’s calculations.

What we have just said indicates that there may no longer be such a thing as a simon-pure investment policy comprising representative common stocks—in the sense that one can always wait to buy them at a price that involves no risk of a market or “quotational” loss large enough to be disquieting. In most periods the investor must recognize the existence of a speculative factor in his common-stock holdings. It is his task to keep this component within minor limits, and to be prepared financially and psychologically for adverse results that may be of short or long duration.

Two paragraphs should be added about stock speculation per se, as distinguished from the speculative component now inherent in most representative common stocks. Outright speculation is neither illegal, immoral, nor (for most people) fattening to the pocketbook. More than that, some speculation is necessary and unavoidable, for in many common-stock situations there are substantial possibilities of both profit and loss, and the risks therein must be assumed by someone.* There is intelligent speculation as there is intelligent investing. But there are many ways in which speculation may be unintelligent. Of these the foremost are: (1) speculating when you think you are investing; (2) speculating seriously instead of as a pastime, when you lack proper knowledge and skill for it; and (3) risking more money in speculation than you can afford to lose.

In our conservative view every nonprofessional who operates on margin † should recognize that he is ipso facto speculating, and it is his broker’s duty so to advise him. And everyone who buys a so-called “hot” common-stock issue, or makes a purchase in any way similar thereto, is either speculating or gambling. Speculation is always fascinating, and it can be a lot of fun while you are ahead of the game. If you want to try your luck at it, put aside a portion—the smaller the better—of your capital in a separate fund for this purpose. Never add more money to this account just because the market has gone up and profits are rolling in. (That’s the time to think of taking money out of your speculative fund.) Never mingle your speculative and investment operations in the same account, nor in any part of your thinking.

Results to Be Expected by the Defensive Investor

We have already defined the defensive investor as one interested chiefly in safety plus freedom from bother. In general what course should he follow and what return can he expect under “average normal conditions”—if such conditions really exist? To answer these questions we shall consider first what we wrote on the subject seven years ago, next what significant changes have occurred since then in the underlying factors governing the investor’s expectable return, and finally what he should do and what he should expect under present-day (early 1972) conditions.

1. What We Said Six Years Ago

We recommended that the investor divide his holdings between high-grade bonds and leading common stocks; that the proportion held in bonds be never less than 25% or more than 75%, with the converse being necessarily true for the common-stock component; that his simplest choice would be to maintain a 50–50 proportion between the two, with adjustments to restore the equality when market developments had disturbed it by as much as, say, 5%. As an alternative policy he might choose to reduce his common-stock component to 25% “if he felt the market was dangerously high,” and conversely to advance it toward the maximum of 75% “if he felt that a decline in stock prices was making them increasingly attractive.”

In 1965 the investor could obtain about 4½% on high-grade taxable bonds and 3¼% on good tax-free bonds. The dividend return on leading common stocks (with the DJIA at 892) was only about 3.2%. This fact, and others, suggested caution. We implied that “at normal levels of the market” the investor should be able to obtain an initial dividend return of between 3½% and 4½% on his stock purchases, to which should be added a steady increase in underlying value (and in the “normal market price”) of a representative stock list of about the same amount, giving a return from dividends and appreciation combined of about 7½% per year. The half and half division between bonds and stocks would yield about 6% before income tax. We added that the stock component should carry a fair degree of protection against a loss of purchasing power caused by large-scale inflation.

It should be pointed out that the above arithmetic indicated expectation of a much lower rate of advance in the stock market than had been realized between 1949 and 1964. That rate had averaged a good deal better than 10% for listed stocks as a whole, and it was quite generally regarded as a sort of guarantee that similarly satisfactory results could be counted on in the future. Few people were willing to consider seriously the possibility that the high rate of advance in the past means that stock prices are “now too high,” and hence that “the wonderful results since 1949 would imply not very good but bad results for the future.”4

2. What Has Happened Since 1964

The major change since 1964 has been the rise in interest rates on first-grade bonds to record high levels, although there has since been a considerable recovery from the lowest prices of 1970. The obtainable return on good corporate issues is now about 7½% and even more against 4½% in 1964. In the meantime the dividend return on DJIA-type stocks had a fair advance also during the market decline of 1969–70, but as we write (with “the Dow” at 900) it is less than 3.5% against 3.2% at the end of 1964. The change in going interest rates produced a maximum decline of about 38% in the market price of medium-term (say 20-year) bonds during this period.

There is a paradoxical aspect to these developments. In 1964 we discussed at length the possibility that the price of stocks might be too high and subject ultimately to a serious decline; but we did not consider specifically the possibility that the same might happen to the price of high-grade bonds. (Neither did anyone else that we know of.) We did warn (on p. 90) that “a long-term bond may vary widely in price in response to changes in interest rates.” In the light of what has since happened we think that this warning—with attendant examples—was insufficiently stressed. For the fact is that if the investor had a given sum in the DJIA at its closing price of 874 in 1964 he would have had a small profit thereon in late 1971; even at the lowest level (631) in 1970 his indicated loss would have been less than that shown on good long-term bonds. On the other hand, if he had confined his bond-type investments to U.S. savings bonds, short-term corporate issues, or savings accounts, he would have had no loss in market value of his principal during this period and he would have enjoyed a higher income return than was offered by good stocks. It turned out, therefore, that true “cash equivalents” proved to be better investments in 1964 than common stocks—in spite of the inflation experience that in theory should have favored stocks over cash. The decline in quoted principal value of good longer-term bonds was due to developments in the money market, an abstruse area which ordinarily does not have an important bearing on the investment policy of individuals.

This is just another of an endless series of experiences over time that have demonstrated that the future of security prices is never predictable.* Almost always bonds have fluctuated much less than stock prices, and investors generally could buy good bonds of any maturity without having to worry about changes in their market value. There were a few exceptions to this rule, and the period after 1964 proved to be one of them. We shall have more to say about change in bond prices in a later chapter.

3. Expectations and Policy in Late 1971 and Early 1972

Toward the end of 1971 it was possible to obtain 8% taxable interest on good medium-term corporate bonds, and 5.7% tax-free on good state or municipal securities. In the shorter-term field the investor could realize about 6% on U.S. government issues due in five years. In the latter case the buyer need not be concerned about a possible loss in market value, since he is sure of full repayment, including the 6% interest return, at the end of a comparatively short holding period. The DJIA at its recurrent price level of 900 in 1971 yields only 3.5%.

Let us assume that now, as in the past, the basic policy decision to be made is how to divide the fund between high-grade bonds (or other so-called “cash equivalents”) and leading DJIA-type stocks. What course should the investor follow under present conditions, if we have no strong reason to predict either a significant upward or a significant downward movement for some time in the future? First let us point out that if there is no serious adverse change, the defensive investor should be able to count on the current 3.5% dividend return on his stocks and also on an average annual appreciation of about 4%. As we shall explain later this appreciation is based essentially on the reinvestment by the various companies of a corresponding amount annually out of undistributed profits. On a before-tax basis the combined return of his stocks would then average, say, 7.5%, somewhat less than his interest on high-grade bonds.* On an after-tax basis the average return on stocks would work out at some 5.3%.5 This would be about the same as is now obtainable on good tax-free medium-term bonds.

These expectations are much less favorable for stocks against bonds than they were in our 1964 analysis. (That conclusion follows inevitably from the basic fact that bond yields have gone up much more than stock yields since 1964.) We must never lose sight of the fact that the interest and principal payments on good bonds are much better protected and therefore more certain than the dividends and price appreciation on stocks. Consequently we are forced to the conclusion that now, toward the end of 1971, bond investment appears clearly preferable to stock investment. If we could be sure that this conclusion is right we would have to advise the defensive investor to put all his money in bonds and none in common stocks until the current yield relationship changes significantly in favor of stocks.

But of course we cannot be certain that bonds will work out better than stocks from today’s levels. The reader will immediately think of the inflation factor as a potent reason on the other side. In the next chapter we shall argue that our considerable experience with inflation in the United States during this century would not support the choice of stocks against bonds at present differentials in yield. But there is always the possibility—though we consider it remote—of an accelerating inflation, which in one way or another would have to make stock equities preferable to bonds payable in a fixed amount of dollars.* There is the alternative possibility—which we also consider highly unlikely—that American business will become so profitable, without stepped-up inflation, as to justify a large increase in common-stock values in the next few years. Finally, there is the more familiar possibility that we shall witness another great speculative rise in the stock market without a real justification in the underlying values. Any of these reasons, and perhaps others we haven’t thought of, might cause the investor to regret a 100% concentration on bonds even at their more favorable yield levels.

Hence, after this foreshortened discussion of the major considerations, we once again enunciate the same basic compromise policy for defensive investors—namely that at all times they have a significant part of their funds in bond-type holdings and a significant part also in equities. It is still true that they may choose between maintaining a simple 50–50 division between the two components or a ratio, dependent on their judgment, varying between a minimum of 25% and a maximum of 75% of either. We shall give our more detailed view of these alternative policies in a later chapter.

Since at present the overall return envisaged from common stocks is nearly the same as that from bonds, the presently expectable return (including growth of stock values) for the investor would change little regardless of how he divides his fund between the two components. As calculated above, the aggregate return from both parts should be about 7.8% before taxes or 5.5% on a tax-free (or estimated tax-paid) basis. A return of this order is appreciably higher than that realized by the typical conservative investor over most of the long-term past. It may not seem attractive in relation to the 14%, or so, return shown by common stocks during the 20 years of the predominantly bull market after 1949. But it should be remembered that between 1949 and 1969 the price of the DJIA had advanced more than fivefold while its earnings and dividends had about doubled. Hence the greater part of the impressive market record for that period was based on a change in investors’ and speculators’ attitudes rather than in underlying corporate values. To that extent it might well be called a “bootstrap operation.”

In discussing the common-stock portfolio of the defensive investor, we have spoken only of leading issues of the type included in the 30 components of the Dow Jones Industrial Average. We have done this for convenience, and not to imply that these 30 issues alone are suitable for purchase by him. Actually, there are many other companies of quality equal to or excelling the average of the Dow Jones list; these would include a host of public utilities (which have a separate Dow Jones average to represent them).* But the major point here is that the defensive investor’s overall results are not likely to be decisively different from one diversified or representative list than from another, or—more accurately—that neither he nor his advisers could predict with certainty whatever differences would ultimately develop. It is true that the art of skillful or shrewd investment is supposed to lie particularly in the selection of issues that will give better results than the general market. For reasons to be developed elsewhere we are skeptical of the ability of defensive investors generally to get better than average results—which in fact would mean to beat their own overall performance.* (Our skepticism extends to the management of large funds by experts.)

Let us illustrate our point by an example that at first may seem to prove the opposite. Between December 1960 and December 1970 the DJIA advanced from 616 to 839, or 36%. But in the same period the much larger Standard & Poor’s weighted index of 500 stocks rose from 58.11 to 92.15, or 58%. Obviously the second group had proved a better “buy” than the first. But who would have been so rash as to predict in 1960 that what seemed like a miscellaneous assortment of all sorts of common stocks would definitely outper-forms the aristocratic “thirty tyrants” of the Dow? All this proves, we insist, that only rarely can one make dependable predictions about price changes, absolute or relative.

We shall repeat here without apology—for the warning cannot be given too often—that the investor cannot hope for better than average results by buying new offerings, or “hot” issues of any sort, meaning thereby those recommended for a quick profit.† The contrary is almost certain to be true in the long run. The defensive investor must confine himself to the shares of important companies with a long record of profitable operations and in strong financial condition. (Any security analyst worth his salt could make up such a list.) Aggressive investors may buy other types of common stocks, but they should be on a definitely attractive basis as established by intelligent analysis.

To conclude this section, let us mention briefly three supplementary concepts or practices for the defensive investor. The first is the purchase of the shares of well-established investment funds as an alternative to creating his own common-stock portfolio. He might also utilize one of the “common trust funds,” or “commingled funds,” operated by trust companies and banks in many states; or, if his funds are substantial, use the services of a recognized investment-counsel firm. This will give him professional administration of his investment program along standard lines. The third is the device of “dollar-cost averaging,” which means simply that the practitioner invests in common stocks the same number of dollars each month or each quarter. In this way he buys more shares when the market is low than when it is high, and he is likely to end up with a satisfactory overall price for all his holdings. Strictly speaking, this method is an application of a broader approach known as “formula investing.” The latter was already alluded to in our suggestion that the investor may vary his holdings of common stocks between the 25% minimum and the 75% maximum, in inverse relationship to the action of the market. These ideas have merit for the defensive investor, and they will be discussed more amply in later chapters.*

Results to Be Expected by the Aggressive Investor

Our enterprising security buyer, of course, will desire and expect to attain better overall results than his defensive or passive companion. But first he must make sure that his results will not be worse. It is no difficult trick to bring a great deal of energy, study, and native ability into Wall Street and to end up with losses instead of profits. These virtues, if channeled in the wrong directions, become indistinguishable from handicaps. Thus it is most essential that the enterprising investor start with a clear conception as to which courses of action offer reasonable chances of success and which do not.

First let us consider several ways in which investors and speculators generally have endeavored to obtain better than average results. These include:

1. TRADING IN THE MARKET. This usually means buying stocks when the market has been advancing and selling them after it has turned downward. The stocks selected are likely to be among those which have been “behaving” better than the market average. A small number of professionals frequently engage in short selling. Here they will sell issues they do not own but borrow through the established mechanism of the stock exchanges. Their object is to benefit from a subsequent decline in the price of these issues, by buying them back at a price lower than they sold them for. (As our quotation from the Wall Street Journal on p. 19 indicates, even “small investors”—perish the term!—sometimes try their unskilled hand at short selling.)

2. SHORT-TERM SELECTIVITY. This means buying stocks of companies which are reporting or expected to report increased earnings, or for which some other favorable development is anticipated.

3. LONG-TERM SELECTIVITY. Here the usual emphasis is on an excellent record of past growth, which is considered likely to continue in the future. In some cases also the “investor” may choose companies which have not yet shown impressive results, but are expected to establish a high earning power later. (Such companies belong frequently in some technological area—e.g., computers, drugs, electronics—and they often are developing new processes or products that are deemed to be especially promising.)

We have already expressed a negative view about the investor’s overall chances of success in these areas of activity. The first we have ruled out, on both theoretical and realistic grounds, from the domain of investment. Stock trading is not an operation “which, on thorough analysis, offers safety of principal and a satisfactory return.” More will be said on stock trading in a later chapter.*

In his endeavor to select the most promising stocks either for the near term or the longer future, the investor faces obstacles of two kinds—the first stemming from human fallibility and the second from the nature of his competition. He may be wrong in his estimate of the future; or even if he is right, the current market price may already fully reflect what he is anticipating. In the area of near-term selectivity, the current year’s results of the company are generally common property on Wall Street; next year’s results, to the extent they are predictable, are already being carefully considered. Hence the investor who selects issues chiefly on the basis of this year’s superior results, or on what he is told he may expect for next year, is likely to find that others have done the same thing for the same reason.

In choosing stocks for their long-term prospects, the investor’s handicaps are basically the same. The possibility of outright error in the prediction—which we illustrated by our airlines example on p. 6—is no doubt greater than when dealing with near-term earnings. Because the experts frequently go astray in such forecasts, it is theoretically possible for an investor to benefit greatly by making correct predictions when Wall Street as a whole is making incorrect ones. But that is only theoretical. How many enterprising investors could count on having the acumen or prophetic gift to beat the professional analysts at their favorite game of estimating long-term future earnings?

We are thus led to the following logical if disconcerting conclusion: To enjoy a reasonable chance for continued better than average results, the investor must follow policies which are (1) inherently sound and promising, and (2) not popular on Wall Street.

Are there any such policies available for the enterprising investor? In theory once again, the answer should be yes; and there are broad reasons to think that the answer should be affirmative in practice as well. Everyone knows that speculative stock movements are carried too far in both directions, frequently in the general market and at all times in at least some of the individual issues. Furthermore, a common stock may be undervalued because of lack of interest or unjustified popular prejudice. We can go further and assert that in an astonishingly large proportion of the trading in common stocks, those engaged therein don’t appear to know—in polite terms—one part of their anatomy from another. In this book we shall point out numerous examples of (past) discrepancies between price and value. Thus it seems that any intelligent person, with a good head for figures, should have a veritable picnic on Wall Street, battening off other people’s foolishness. So it seems, but somehow it doesn’t work out that simply. Buying a neglected and therefore undervalued issue for profit generally proves a protracted and patience-trying experience. And selling short a too popular and therefore overvalued issue is apt to be a test not only of one’s courage and stamina but also of the depth of one’s pocketbook.* The principle is sound, its successful application is not impossible, but it is distinctly not an easy art to master.

There is also a fairly wide group of “special situations,” which over many years could be counted on to bring a nice annual return of 20% or better, with a minimum of overall risk to those who knew their way around in this field. They include intersecurity arbitrages, payouts or workouts in liquidations, protected hedges of certain kinds. The most typical case is a projected merger or acquisition which offers a substantially higher value for certain shares than their price on the date of the announcement. The number of such deals increased greatly in recent years, and it should have been a highly profitable period for the cognoscenti. But with the multiplication of merger announcements came a multiplication of obstacles to mergers and of deals that didn’t go through; quite a few individual losses were thus realized in these once-reliable operations. Perhaps, too, the overall rate of profit was diminished by too much competition.†

The lessened profitability of these special situations appears one manifestation of a kind of self-destructive process—akin to the law of diminishing returns—which has developed during the lifetime of this book. In 1949 we could present a study of stock-market fluctuations over the preceding 75 years, which supported a formula—based on earnings and current interest rates—for determining a level to buy the DJIA below its “central” or “intrinsic” value, and to sell out above such value. It was an application of the governing maxim of the Rothschilds: “Buy cheap and sell dear.”* And it had the advantage of running directly counter to the ingrained and pernicious maxim of Wall Street that stocks should be bought because they have gone up and sold because they have gone down. Alas, after 1949 this formula no longer worked. A second illustration is provided by the famous “Dow Theory” of stock-market movements, in a comparison of its indicated splendid results for 1897–1933 and its much more questionable performance since 1934.

A third and final example of the golden opportunities not recently available: A good part of our own operations on Wall Street had been concentrated on the purchase of bargain issues easily identified as such by the fact that they were selling at less than their share in the net current assets (working capital) alone, not counting the plant account and other assets, and after deducting all liabilities ahead of the stock. It is clear that these issues were selling at a price well below the value of the enterprise as a private business. No proprietor or majority holder would think of selling what he owned at so ridiculously low a figure. Strangely enough, such anomalies were not hard to find. In 1957 a list was published showing nearly 200 issues of this type available in the market. In various ways practically all these bargain issues turned out to be profitable, and the average annual result proved much more remunerative than most other investments. But they too virtually disappeared from the stock market in the next decade, and with them a dependable area for shrewd and successful operation by the enterprising investor. However, at the low prices of 1970 there again appeared a considerable number of such “sub-working-capital” issues, and despite the strong recovery of the market, enough of them remained at the end of the year to make up a full-sized portfolio.

The enterprising investor under today’s conditions still has various possibilities of achieving better than average results. The huge list of marketable securities must include a fair number that can be identified as undervalued by logical and reasonably dependable standards. These should yield more satisfactory results on the average than will the DJIA or any similarly representative list. In our view the search for these would not be worth the investor’s effort unless he could hope to add, say, 5% before taxes to the average annual return from the stock portion of his portfolio. We shall try to develop one or more such approaches to stock selection for use by the active investor.

Commentary on Chapter 1

All of human unhappiness comes from one single thing: not knowing how to remain at rest in a room.

—Blaise Pascal

Why do you suppose the brokers on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange always cheer at the sound of the closing bell—no matter what the market did that day? Because whenever you trade, they make money—whether you did or not. By speculating instead of investing, you lower your own odds of building wealth and raise someone else’s.

Graham’s definition of investing could not be clearer: “An investment operation is one which, upon thorough analysis, promises safety of principal and an adequate return.”1 Note that investing, according to Graham, consists equally of three elements:

- you must thoroughly analyze a company, and the soundness of its underlying businesses, before you buy its stock;

- you must deliberately protect yourself against serious losses;

- you must aspire to “adequate,” not extraordinary, performance.

An investor calculates what a stock is worth, based on the value of its businesses. A speculator gambles that a stock will go up in price because somebody else will pay even more for it. As Graham once put it, investors judge “the market price by established standards of value,” while speculators “base [their] standards of value upon the market price.”2 For a speculator, the incessant stream of stock quotes is like oxygen; cut it off and he dies. For an investor, what Graham called “quotational” values matter much less. Graham urges you to invest only if you would be comfortable owning a stock even if you had no way of knowing its daily share price.3

Like casino gambling or betting on the horses, speculating in the market can be exciting or even rewarding (if you happen to get lucky). But it’s the worst imaginable way to build your wealth. That’s because Wall Street, like Las Vegas or the racetrack, has calibrated the odds so that the house always prevails, in the end, against everyone who tries to beat the house at its own speculative game.

On the other hand, investing is a unique kind of casino—one where you cannot lose in the end, so long as you play only by the rules that put the odds squarely in your favor. People who invest make money for themselves; people who speculate make money for their brokers. And that, in turn, is why Wall Street perennially downplays the durable virtues of investing and hypes the gaudy appeal of speculation.

Unsafe at High Speed

Confusing speculation with investment, Graham warns, is always a mistake. In the 1990s, that confusion led to mass destruction. Almost everyone, it seems, ran out of patience at once, and America became the Speculation Nation, populated with traders who went shooting from stock to stock like grasshoppers whizzing around in an August hay field.

People began believing that the test of an investment technique was simply whether it “worked.” If they beat the market over any period, no matter how dangerous or dumb their tactics, people boasted that they were “right.” But the intelligent investor has no interest in being temporarily right. To reach your long-term financial goals, you must be sustainably and reliably right. The techniques that became so trendy in the 1990s—day trading, ignoring diversification, flipping hot mutual funds, following stock-picking “systems”—seemed to work. But they had no chance of prevailing in the long run, because they failed to meet all three of Graham’s criteria for investing.

To see why temporarily high returns don’t prove anything, imagine that two places are 130 miles apart. If I observe the 65-mph speed limit, I can drive that distance in two hours. But if I drive 130 mph, I can get there in one hour. If I try this and survive, am I “right”? Should you be tempted to try it, too, because you hear me bragging that it “worked”? Flashy gimmicks for beating the market are much the same: In short streaks, so long as your luck holds out, they work. Over time, they will get you killed.

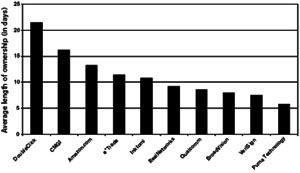

In 1973, when Graham last revised The Intelligent Investor, the annual turnover rate on the New York Stock Exchange was 20%, meaning that the typical shareholder held a stock for five years before selling it. By 2002, the turnover rate had hit 105%—a holding period of only 11.4 months. Back in 1973, the average mutual fund held on to a stock for nearly three years; by 2002, that ownership period had shrunk to just 10.9 months. It’s as if mutual-fund managers were studying their stocks just long enough to learn they shouldn’t have bought them in the first place, then promptly dumping them and starting all over.

Even the most respected money-management firms got antsy. In early 1995, Jeffrey Vinik, manager of Fidelity Magellan (then the world’s largest mutual fund), had 42.5% of its assets in technology stocks. Vinik proclaimed that most of his shareholders “have invested in the fund for goals that are years away…. I think their objectives are the same as mine, and that they believe, as I do, that a long-term approach is best.” But six months after he wrote those high-minded words, Vinik sold off almost all his technology shares, unloading nearly $19 billion worth in eight frenzied weeks. So much for the “long term”! And by 1999, Fidelity’s discount brokerage division was egging on its clients to trade anywhere, anytime, using a Palm handheld computer—which was perfectly in tune with the firm’s new slogan, “Every second counts.”

FIGURE 1-1

Stocks on Speed

And on the NASDAQ exchange, turnover hit warp speed, as Figure 1-1 shows.4

In 1999, shares in Puma Technology, for instance, changed hands an average of once every 5.7 days. Despite NASDAQ’s grandiose motto—“The Stock Market for the Next Hundred Years”—many of its customers could barely hold on to a stock for a hundred hours.

The Financial Video Game

Wall Street made online trading sound like an instant way to mint money: Discover Brokerage, the online arm of the venerable firm of Morgan Stanley, ran a TV commercial in which a scruffy tow-truck driver picks up a prosperous-looking executive. Spotting a photo of a tropical beachfront posted on the dashboard, the executive asks, “Vacation?” “Actually,” replies the driver, “that’s my home.” Taken aback, the suit says, “Looks like an island.” With quiet triumph, the driver answers, “Technically, it’s a country.”

The propaganda went further. Online trading would take no work and require no thought. A television ad from Ameritrade, the online broker, showed two housewives just back from jogging; one logs on to her computer, clicks the mouse a few times, and exults, “I think I just made about $1,700!” In a TV commercial for the Waterhouse brokerage firm, someone asked basketball coach Phil Jackson, “You know anything about the trade?” His answer: “I’m going to make it right now.” (How many games would Jackson’s NBA teams have won if he had brought that philosophy to courtside? Somehow, knowing nothing about the other team, but saying, “I’m ready to play them right now,” doesn’t sound like a championship formula.)

By 1999 at least six million people were trading online—and roughly a tenth of them were “day trading,” using the Internet to buy and sell stocks at lightning speed. Everyone from showbiz diva Barbra Streisand to Nicholas Birbas, a 25-year-old former waiter in Queens, New York, was flinging stocks around like live coals. “Before,” scoffed Birbas, “I was investing for the long term and I found out that it was not smart.” Now, Birbas traded stocks up to 10 times a day and expected to earn $100,000 in a year. “I can’t stand to see red in my profit-or-loss column,” Streisand shuddered in an interview with Fortune. “I’m Taurus the bull, so I react to red. If I see red, I sell my stocks quickly.”5

By pouring continuous data about stocks into bars and barbershops, kitchens and cafés, taxicabs and truck stops, financial websites and financial TV turned the stock market into a nonstop national video game. The public felt more knowledgeable about the markets than ever before. Unfortunately, while people were drowning in data, knowledge was nowhere to be found. Stocks became entirely decoupled from the companies that had issued them—pure abstractions, just blips moving across a TV or computer screen. If the blips were moving up, nothing else mattered.

On December 20, 1999, Juno Online Services unveiled a trailblazing business plan: to lose as much money as possible, on purpose. Juno announced that it would henceforth offer all its retail services for free—no charge for e-mail, no charge for Internet access—and that it would spend millions of dollars more on advertising over the next year. On this declaration of corporate hara-kiri, Juno’s stock roared up from $16.375 to $66.75 in two days.6

Why bother learning whether a business was profitable, or what goods or services a company produced, or who its management was, or even what the company’s name was? All you needed to know about stocks was the catchy code of their ticker symbols: CBLT, INKT, PCLN, TGLO, VRSN, WBVN.7 That way you could buy them even faster, without the pesky two-second delay of looking them up on an Internet search engine. In late 1998, the stock of a tiny, rarely traded building-maintenance company, Temco Services, nearly tripled in a matter of minutes on record-high volume. Why? In a bizarre form of financial dyslexia, thousands of traders bought Temco after mistaking its ticker symbol, TMCO, for that of Ticketmaster Online (TMCS), an Internet darling whose stock began trading publicly for the first time that day.8

Oscar Wilde joked that a cynic “knows the price of everything, and the value of nothing.” Under that definition, the stock market is always cynical, but by the late 1990s it would have shocked Oscar himself. A single half-baked opinion on price could double a company’s stock even as its value went entirely unexamined. In late 1998, Henry Blodget, an analyst at CIBC Oppenheimer, warned that “as with all Internet stocks, a valuation is clearly more art than science.” Then, citing only the possibility of future growth, he jacked up his “price target” on Amazon.com from $150 to $400 in one fell swoop. Amazon.com shot up 19% that day and—despite Blodget’s protest that his price target was a one-year forecast—soared past $400 in just three weeks. A year later, PaineWebber analyst Walter Piecyk predicted that Qualcomm stock would hit $1,000 a share over the next 12 months. The stock—already up 1,842% that year—soared another 31% that day, hitting $659 a share.9

From Formula to Fiasco

But trading as if your underpants are on fire is not the only form of speculation. Throughout the past decade or so, one speculative formula after another was promoted, popularized, and then thrown aside. All of them shared a few traits—This is quick! This is easy! And it won’t hurt a bit!—and all of them violated at least one of Graham’s distinctions between investing and speculating. Here are a few of the trendy formulas that fell flat:

- Cash in on the calendar. The “January effect”—the tendency of small stocks to produce big gains around the turn of the year—was widely promoted in scholarly articles and popular books published in the 1980s. These studies showed that if you piled into small stocks in the second half of December and held them into January, you would beat the market by five to 10 percentage points. That amazed many experts. After all, if it were this easy, surely everyone would hear about it, lots of people would do it, and the opportunity would wither away.

What caused the January jolt? First of all, many investors sell their crummiest stocks late in the year to lock in losses that can cut their tax bills. Second, professional money managers grow more cautious as the year draws to a close, seeking to preserve their outperformance (or minimize their underperformance). That makes them reluctant to buy (or even hang on to) a falling stock. And if an underperforming stock is also small and obscure, a money manager will be even less eager to show it in his year-end list of holdings. All these factors turn small stocks into momentary bargains; when the tax-driven selling ceases in January, they typically bounce back, producing a robust and rapid gain.

The January effect has not withered away, but it has weakened. According to finance professor William Schwert of the University of Rochester, if you had bought small stocks in late December and sold them in early January, you would have beaten the market by 8.5 percentage points from 1962 through 1979, by 4.4 points from 1980 through 1989, and by 5.8 points from 1990 through 2001.10

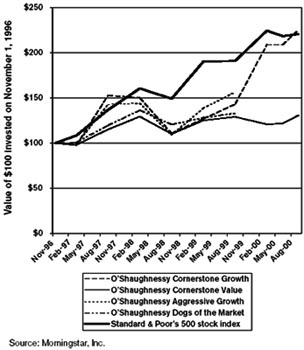

As more people learned about the January effect, more traders bought small stocks in December, making them less of a bargain and thus reducing their returns. Also, the January effect is biggest among the smallest stocks—but according to Plexus Group, the leading authority on brokerage expenses, the total cost of buying and selling such tiny stocks can run up to 8% of your investment.11 Sadly, by the time you’re done paying your broker, all your gains on the January effect will melt away. - Just do “what works.” In 1996, an obscure money manager named James O’Shaughnessy published a book called What Works on Wall Street. In it, he argued that “investors can do much better than the market.” O’Shaughnessy made a stunning claim: From 1954 through 1994, you could have turned $10,000 into $8,074,504, beating the market by more than 10-fold—a towering 18.2% average annual return. How? By buying a basket of 50 stocks with the highest one-year returns, five straight years of rising earnings, and share prices less than 1.5 times their corporate revenues.12 As if he were the Edison of Wall Street, O’Shaughnessy obtained U.S. Patent No. 5,978,778 for his “automated strategies” and launched a group of four mutual funds based on his findings. By late 1999 the funds had sucked in more than $175 million from the public—and, in his annual letter to shareholders, O’Shaughnessy stated grandly: “As always, I hope that together, we can reach our long-term goals by staying the course and sticking with our time-tested investment strategies.”

But “what works on Wall Street” stopped working right after O’Shaughnessy publicized it. As Figure 1-2 shows, two of his funds stank so badly that they shut down in early 2000, and the overall stock market (as measured by the S & P 500 index) walloped every O’Shaughnessy fund almost nonstop for nearly four years running.FIGURE 1-2

What Used to Work on Wall Street…

In June 2000, O’Shaughnessy moved closer to his own “long-term goals” by turning the funds over to a new manager, leaving his customers to fend for themselves with those “time-tested investment strategies.”13 O’Shaughnessy’s shareholders might have been less upset if he had given his book a more precise title—for instance, What Used to Work on Wall Street…Until I Wrote This Book. - Follow “The Foolish Four.” In the mid-1990s, the Motley Fool website (and several books) hyped the daylights out of a technique called “The Foolish Four.” According to the Motley Fool, you would have “trashed the market averages over the last 25 years” and could “crush your mutual funds” by spending “only 15 minutes a year” on planning your investments. Best of all, this technique had “minimal risk.” All you needed to do was this:

- Take the five stocks in the Dow Jones Industrial Average with the lowest stock prices and highest dividend yields.

- Discard the one with the lowest price.

- Put 40% of your money in the stock with the second-lowest price.

- Put 20% in each of the three remaining stocks.

- One year later, sort the Dow the same way and reset the portfolio according to steps 1 through 4.

- Repeat until wealthy.

Over a 25-year period, the Motley Fool claimed, this technique would have beaten the market by a remarkable 10.1 percentage points annually. Over the next two decades, they suggested, $20,000 invested in The Foolish Four should flower into $1,791,000. (And, they claimed, you could do still better by picking the five Dow stocks with the highest ratio of dividend yield to the square root of stock price, dropping the one that scored the highest, and buying the next four.)

Let’s consider whether this “strategy” could meet Graham’s definitions of an investment:

- What kind of “thorough analysis” could justify discarding the stock with the single most attractive price and dividend—but keeping the four that score lower for those desirable qualities?

- How could putting 40% of your money into only one stock be a “minimal risk”?

- And how could a portfolio of only four stocks be diversified enough to provide “safety of principal”?

The Foolish Four, in short, was one of the most cockamamie stock-picking formulas ever concocted. The Fools made the same mistake as O’Shaughnessy: If you look at a large quantity of data long enough, a huge number of patterns will emerge—if only by chance. By random luck alone, the companies that produce above-average stock returns will have plenty of things in common. But unless those factors cause the stocks to outper-forms, they can’t be used to predict future returns.

None of the factors that the Motley Fools “discovered” with such fanfare—dropping the stock with the best score, doubling up on the one with the second-highest score, dividing the dividend yield by the square root of stock price—could possibly cause or explain the future performance of a stock. Money Magazine found that a portfolio made up of stocks whose names contained no repeating letters would have performed nearly as well as The Foolish Four—and for the same reason: luck alone.14 As Graham never stops reminding us, stocks do well or poorly in the future because the businesses behind them do well or poorly—nothing more, and nothing less.

Sure enough, instead of crushing the market, The Foolish Four crushed the thousands of people who were fooled into believing that it was a form of investing. In 2000 alone, the four Foolish stocks—Caterpillar, Eastman Kodak, SBC, and General Motors—lost 14% while the Dow dropped by just 4.7%.

As these examples show, there’s only one thing that never suffers a bear market on Wall Street: dopey ideas. Each of these so-called investing approaches fell prey to Graham’s Law. All mechanical formulas for earning higher stock performance are “a kind of self-destructive process—akin to the law of diminishing returns.” There are two reasons the returns fade away. If the formula was just based on random statistical flukes (like The Foolish Four), the mere passage of time will expose that it made no sense in the first place. On the other hand, if the formula actually did work in the past (like the January effect), then by publicizing it, market pundits always erode—and usually eliminate—its ability to do so in the future.

All this reinforces Graham’s warning that you must treat speculation as veteran gamblers treat their trips to the casino:

- You must never delude yourself into thinking that you’re investing when you’re speculating.

- Speculating becomes mortally dangerous the moment you begin to take it seriously.

- You must put strict limits on the amount you are willing to wager.

Just as sensible gamblers take, say, $100 down to the casino floor and leave the rest of their money locked in the safe in their hotel room, the intelligent investor designates a tiny portion of her total portfolio as a “mad money” account. For most of us, 10% of our overall wealth is the maximum permissible amount to put at speculative risk. Never mingle the money in your speculative account with what’s in your investment accounts; never allow your speculative thinking to spill over into your investing activities; and never put more than 10% of your assets into your mad money account, no matter what happens.

For better or worse, the gambling instinct is part of human nature—so it’s futile for most people even to try suppressing it. But you must confine and restrain it. That’s the single best way to make sure you will never fool yourself into confusing speculation with investment.