Investment Merits of Common Stocks

In our first edition (1949) we found it necessary at this point to insert a long exposition of the case for including a substantial common-stock component in all investment portfolios.* Common stocks were generally viewed as highly speculative and therefore unsafe; they had declined fairly substantially from the high levels of 1946, but instead of attracting investors to them because of their reasonable prices, this fall had had the opposite effect of undermining confidence in equity securities. We have commented on the converse situation that has developed in the ensuing 20 years, whereby the big advance in stock prices made them appear safe and profitable investments at record high levels which might actually carry with them a considerable degree of risk.†

The argument we made for common stocks in 1949 turned on two main points. The first was that they had offered a considerable degree of protection against the erosion of the investor’s dollar caused by inflation, whereas bonds offered no protection at all. The second advantage of common stocks lay in their higher average return to investors over the years. This was produced both by an average dividend income exceeding the yield on good bonds and by an underlying tendency for market value to increase over the years in consequence of the reinvestment of undistributed profits.

While these two advantages have been of major importance—and have given common stocks a far better record than bonds over the long-term past—we have consistently warned that these benefits could be lost by the stock buyer if he pays too high a price for his shares. This was clearly the case in 1929, and it took 25 years for the market level to climb back to the ledge from which it had abysmally fallen in 1929–1932.* Since 1957 common stocks have once again, through their high prices, lost their traditional advantage in dividend yield over bond interest rates.† It remains to be seen whether the inflation factor and the economic-growth factor will make up in the future for this significantly adverse development.

It should be evident to the reader that we have no enthusiasm for common stocks in general at the 900 DJIA level of late 1971. For reasons already given* we feel that the defensive investor cannot afford to be without an appreciable proportion of common stocks in his portfolio, even if he must regard them as the lesser of two evils—the greater being the risks attached to an all-bond holding.

Rules for the Common-Stock Component

The selection of common stocks for the portfolio of the defensive investor should be a relatively simple matter. Here we would suggest four rules to be followed:

1. There should be adequate though not excessive diversification. This might mean a minimum of ten different issues and a maximum of about thirty.†

2. Each company selected should be large, prominent, and conservatively financed. Indefinite as these adjectives must be, their general sense is clear. Observations on this point are added at the end of the chapter.

3. Each company should have a long record of continuous dividend payments. (All the issues in the Dow Jones Industrial Average met this dividend requirement in 1971.) To be specific on this point we would suggest the requirement of continuous dividend payments beginning at least in 1950.*

4. The investor should impose some limit on the price he will pay for an issue in relation to its average earnings over, say, the past seven years. We suggest that this limit be set at 25 times such average earnings, and not more than 20 times those of the last twelve-month period. But such a restriction would eliminate nearly all the strongest and most popular companies from the portfolio. In particular, it would ban virtually the entire category of “growth stocks,” which have for some years past been the favorites of both speculators and institutional investors. We must give our reasons for proposing so drastic an exclusion.

Growth Stocks and the Defensive Investor

The term “growth stock” is applied to one which has increased its per-share earnings in the past at well above the rate for common stocks generally and is expected to continue to do so in the future. (Some authorities would say that a true growth stock should be expected at least to double its per-share earnings in ten years—i.e., to increase them at a compounded annual rate of over 7.1%.)† Obviously stocks of this kind are attractive to buy and to own, provided the price paid is not excessive. The problem lies there, of course, since growth stocks have long sold at high prices in relation to current earnings and at much higher multiples of their average profits over a past period. This has introduced a speculative element of considerable weight in the growth-stock picture and has made successful operations in this field a far from simple matter.

The leading growth issue has long been International Business Machines, and it has brought phenomenal rewards to those who bought it years ago and held on to it tenaciously. But we have already pointed out* that this “best of common stocks” actually lost 50% of its market price in a six-months’ decline during 1961–62 and nearly the same percentage in 1969–70. Other growth stocks have been even more vulnerable to adverse developments; in some cases not only has the price fallen back but the earnings as well, thus causing a double discomfiture to those who owned them. A good second example for our purpose is Texas Instruments, which in six years rose from 5 to 256, without paying a dividend, while its earnings increased from 40 cents to $3.91 per share. (Note that the price advanced five times as fast as the profits; this is characteristic of popular common stocks.) But two years later the earnings had dropped off by nearly 50% and the price by four-fifths, to 49.†

The reader will understand from these instances why we regard growth stocks as a whole as too uncertain and risky a vehicle for the defensive investor. Of course, wonders can be accomplished with the right individual selections, bought at the right levels, and later sold after a huge rise and before the probable decline. But the average investor can no more expect to accomplish this than to find money growing on trees. In contrast we think that the group of large companies that are relatively unpopular, and therefore obtainable at reasonable earnings multipliers,* offers a sound if unspectacular area of choice by the general public. We shall illustrate this idea in our chapter on portfolio selection.

Portfolio Changes

It is now standard practice to submit all security lists for periodic inspection in order to see whether their quality can be improved. This, of course, is a major part of the service provided for clients by investment counselors. Nearly all brokerage houses are ready to make corresponding suggestions, without special fee, in return for the commission business involved. Some brokerage houses maintain investment services on a fee basis.

Presumably our defensive investor should obtain—at least once a year—the same kind of advice regarding changes in his portfolio as he sought when his funds were first committed. Since he will have little expertness of his own on which to rely, it is essential that he entrust himself only to firms of the highest reputation; otherwise he may easily fall into incompetent or unscrupulous hands. It is important, in any case, that at every such consultation he make clear to his adviser that he wishes to adhere closely to the four rules of common-stock selection given earlier in this chapter. Incidentally, if his list has been competently selected in the first instance, there should be no need for frequent or numerous changes.†

Dollar-Cost Averaging

The New York Stock Exchange has put considerable effort into popularizing its “monthly purchase plan,” under which an investor devotes the same dollar amount each month to buying one or more common stocks. This is an application of a special type of “formula investment” known as dollar-cost averaging. During the predominantly rising-market experience since 1949 the results from such a procedure were certain to be highly satisfactory, especially since they prevented the practitioner from concentrating his buying at the wrong times.

In Lucile Tomlinson’s comprehensive study of formula investment plans,1 the author presented a calculation of the results of dollar-cost averaging in the group of stocks making up the Dow Jones industrial index. Tests were made covering 23 ten-year purchase periods, the first ending in 1929, the last in 1952. Every test showed a profit either at the close of the purchase period or within five years thereafter. The average indicated profit at the end of the 23 buying periods was 21.5%, exclusive of dividends received. Needless to say, in some instances there was a substantial temporary depreciation at market value. Miss Tomlinson ends her discussion of this ultrasimple investment formula with the striking sentence: “No one has yet discovered any other formula for investing which can be used with so much confidence of ultimate success, regardless of what may happen to security prices, as Dollar Cost Averaging.”

It may be objected that dollar-cost averaging, while sound in principle, is rather unrealistic in practice, because few people are so situated that they can have available for common-stock investment the same amount of money each year for, say, 20 years. It seems to me that this apparent objection has lost much of its force in recent years. Common stocks are becoming generally accepted as a necessary component of a sound savings-investment program. Thus, systematic and uniform purchases of common stocks may present no more psychological and financial difficulties than similar continuous payments for United States savings bonds and for life insurance—to which they should be complementary. The monthly amount may be small, but the results after 20 or more years can be impressive and important to the saver.

The Investor’s Personal Situation

At the beginning of this chapter we referred briefly to the position of the individual portfolio owner. Let us return to this matter, in the light of our subsequent discussion of general policy. To what extent should the type of securities selected by the investor vary with his circumstances? As concrete examples representing widely different conditions, we shall take: (1) a widow left $200,000 with which to support herself and her children; (2) a successful doctor in mid-career, with savings of $100,000 and yearly accretions of $10,000; and (3) a young man earning $200 per week and saving $1,000 a year.*

For the widow, the problem of living on her income is a very difficult one. On the other hand the need for conservatism in her investments is paramount. A division of her fund about equally between United States bonds and first-grade common stocks is a compromise between these objectives and corresponds to our general prescription for the defensive investor. (The stock component may be placed as high as 75% if the investor is psychologically prepared for this decision, and if she can be almost certain she is not buying at too high a level. Assuredly this is not the case in early 1972.)

We do not preclude the possibility that the widow may qualify as an enterprising investor, in which case her objectives and methods will be quite different. The one thing the widow must not do is to take speculative chances in order to “make some extra income.” By this we mean trying for profits or high income without the necessary equipment to warrant full confidence in overall success. It would be far better for her to draw $2,000 per year out of her principal, in order to make both ends meet, than to risk half of it in poorly grounded, and therefore speculative, ventures.

The prosperous doctor has none of the widow’s pressures and compulsions, yet we believe that his choices are pretty much the same. Is he willing to take a serious interest in the business of investment? If he lacks the impulse or the flair, he will do best to accept the easy role of the defensive investor. The division of his portfolio should then be no different from that of the “typical” widow, and there would be the same area of personal choice in fixing the size of the stock component. The annual savings should be invested in about the same proportions as the total fund.

The average doctor may be more likely than the average widow to elect to become an enterprising investor, and he is perhaps more likely to succeed in the undertaking. He has one important handicap, however—the fact that he has less time available to give to his investment education and to the administration of his funds. In fact, medical men have been notoriously unsuccessful in their security dealings. The reason for this is that they usually have an ample confidence in their own intelligence and a strong desire to make a good return on their money, without the realization that to do so successfully requires both considerable attention to the matter and something of a professional approach to security values.

Finally, the young man who saves $1,000 a year—and expects to do better gradually—finds himself with the same choices, though for still different reasons. Some of his savings should go automatically into Series E bonds. The balance is so modest that it seems hardly worthwhile for him to undergo a tough educational and temperamental discipline in order to qualify as an aggressive investor. Thus a simple resort to our standard program for the defensive investor would be at once the easiest and the most logical policy.

Let us not ignore human nature at this point. Finance has a fascination for many bright young people with limited means. They would like to be both intelligent and enterprising in the placement of their savings, even though investment income is much less important to them than their salaries. This attitude is all to the good. There is a great advantage for the young capitalist to begin his financial education and experience early. If he is going to operate as an aggressive investor he is certain to make some mistakes and to take some losses. Youth can stand these disappointments and profit by them. We urge the beginner in security buying not to waste his efforts and his money in trying to beat the market. Let him study security values and initially test out his judgment on price versus value with the smallest possible sums.

Thus we return to the statement, made at the outset, that the kind of securities to be purchased and the rate of return to be sought depend not on the investor’s financial resources but on his financial equipment in terms of knowledge, experience, and temperament.

Note on the Concept of “Risk”

It is conventional to speak of good bonds as less risky than good preferred stocks and of the latter as less risky than good common stocks. From this was derived the popular prejudice against common stocks because they are not “safe,” which was demonstrated in the Federal Reserve Board’s survey of 1948. We should like to point out that the words “risk” and “safety” are applied to securities in two different senses, with a resultant confusion in thought.

A bond is clearly proved unsafe when it defaults its interest or principal payments. Similarly, if a preferred stock or even a common stock is bought with the expectation that a given rate of dividend will be continued, then a reduction or passing of the dividend means that it has proved unsafe. It is also true that an investment contains a risk if there is a fair possibility that the holder may have to sell at a time when the price is well below cost.

Nevertheless, the idea of risk is often extended to apply to a possible decline in the price of a security, even though the decline may be of a cyclical and temporary nature and even though the holder is unlikely to be forced to sell at such times. These chances are present in all securities, other than United States savings bonds, and to a greater extent in the general run of common stocks than in senior issues as a class. But we believe that what is here involved is not a true risk in the useful sense of the term. The man who holds a mortgage on a building might have to take a substantial loss if he were forced to sell it at an unfavorable time. That element is not taken into account in judging the safety or risk of ordinary real-estate mortgages, the only criterion being the certainty of punctual payments. In the same way the risk attached to an ordinary commercial business is measured by the chance of its losing money, not by what would happen if the owner were forced to sell.

In Chapter 8 we shall set forth our conviction that the bona fide investor does not lose money merely because the market price of his holdings declines; hence the fact that a decline may occur does not mean that he is running a true risk of loss. If a group of well-selected common-stock investments shows a satisfactory overall return, as measured through a fair number of years, then this group investment has proved to be “safe.” During that period its market value is bound to fluctuate, and as likely as not it will sell for a while under the buyer’s cost. If that fact makes the investment “risky,” it would then have to be called both risky and safe at the same time. This confusion may be avoided if we apply the concept of risk solely to a loss of value which either is realized through actual sale, or is caused by a significant deterioration in the company’s position—or, more frequently perhaps, is the result of the payment of an excessive price in relation to the intrinsic worth of the security.2

Many common stocks do involve risks of such deterioration. But it is our thesis that a properly executed group investment in common stocks does not carry any substantial risk of this sort and that therefore it should not be termed “risky” merely because of the element of price fluctuation. But such risk is present if there is danger that the price may prove to have been clearly too high by intrinsic-value standards—even if any subsequent severe market decline may be recouped many years later.

Note on the Category of “Large, Prominent, and Conservatively Financed Corporations”

The quoted phrase in our caption was used earlier in the chapter to describe the kind of common stocks to which defensive investors should limit their purchases—provided also that they had paid continuous dividends for a considerable number of years. A criterion based on adjectives is always ambiguous. Where is the dividing line for size, for prominence, and for conservatism of financial structure? On the last point we can suggest a specific standard that, though arbitrary, is in line with accepted thinking. An industrial company’s finances are not conservative unless the common stock (at book value) represents at least half of the total capitalization, including all bank debt.3 For a railroad or public utility the figure should be at least 30%.

The words “large” and “prominent” carry the notion of substantial size combined with a leading position in the industry. Such companies are often referred to as “primary”; all other common stocks are then called “secondary,” except that growth stocks are ordinarily placed in a separate class by those who buy them as such. To supply an element of concreteness here, let us suggest that to be “large” in present-day terms a company should have $50 million of assets or do $50 million of business.* Again to be “prominent” a company should rank among the first quarter or first third in size within its industry group.

It would be foolish, however, to insist upon such arbitrary criteria. They are offered merely as guides to those who may ask for guidance. But any rule which the investor may set for himself and which does no violence to the common-sense meanings of “large” and “prominent” should be acceptable. By the very nature of the case there must be a large group of companies that some will and others will not include among those suitable for defensive investment. There is no harm in such diversity of opinion and action. In fact, it has a salutary effect upon stock-market conditions, because it permits a gradual differentiation or transition between the categories of primary and secondary stock issues.

Commentary on Chapter 5

Human felicity is produc’d not so much by great Pieces of good Fortune that seldom happen, as by little Advantages that occur every day.

—Benjamin Franklin

The Best Defense is a Good Offense

After the stock-market bloodbath of the past few years, why would any defensive investor put a dime into stocks?

First, remember Graham’s insistence that how defensive you should be depends less on your tolerance for risk than on your willingness to put time and energy into your portfolio. And if you go about it the right way, investing in stocks is just as easy as parking your money in bonds and cash. (As we’ll see in Chapter 9, you can buy a stock-market index fund with no more effort than it takes to get dressed in the morning.)

Amidst the bear market that began in 2000, it’s understandable if you feel burned—and if, in turn, that feeling makes you determined never to buy another stock again. As an old Turkish proverb says, “After you burn your mouth on hot milk, you blow on your yogurt.” Because the crash of 2000–2002 was so terrible, many investors now view stocks as scaldingly risky; but, paradoxically, the very act of crashing has taken much of the risk out of the stock market. It was hot milk before, but it is room-temperature yogurt now.

Viewed logically, the decision of whether to own stocks today has nothing to do with how much money you might have lost by owning them a few years ago. When stocks are priced reasonably enough to give you future growth, then you should own them, regardless of the losses they may have cost you in the recent past. That’s all the more true when bond yields are low, reducing the future returns on income-producing investments.

As we have seen in Chapter 3, stocks are (as of early 2003) only mildly overpriced by historical standards. Meanwhile, at recent prices, bonds offer such low yields that an investor who buys them for their supposed safety is like a smoker who thinks he can protect himself against lung cancer by smoking low-tar cigarettes. No matter how defensive an investor you are—in Graham’s sense of low maintenance, or in the contemporary sense of low risk—today’s values mean that you must keep at least some of your money in stocks.

Fortunately, it’s never been easier for a defensive investor to buy stocks. And a permanent autopilot portfolio, which effortlessly puts a little bit of your money to work every month in predetermined investments, can defend you against the need to dedicate a large part of your life to stock picking.

Should You “Buy What You Know”?

But first, let’s look at something the defensive investor must always defend against: the belief that you can pick stocks without doing any homework. In the 1980s and early 1990s, one of the most popular investing slogans was “buy what you know.” Peter Lynch—who from 1977 through 1990 piloted Fidelity Magellan to the best track record ever compiled by a mutual fund—was the most charismatic preacher of this gospel. Lynch argued that amateur investors have an advantage that professional investors have forgotten how to use: “the power of common knowledge.” If you discover a great new restaurant, car, toothpaste, or jeans—or if you notice that the parking lot at a nearby business is always full or that people are still working at a company’s headquarters long after Jay Leno goes off the air—then you have a personal insight into a stock that a professional analyst or portfolio manager might never pick up on. As Lynch put it, “During a lifetime of buying cars or cameras, you develop a sense of what’s good and what’s bad, what sells and what doesn’t…and the most important part is, you know it before Wall Street knows it.”1

Lynch’s rule—“You can outper-forms the experts if you use your edge by investing in companies or industries you already understand”—isn’t totally implausible, and thousands of investors have profited from it over the years. But Lynch’s rule can work only if you follow its corollary as well: “Finding the promising company is only the first step. The next step is doing the research.” To his credit, Lynch insists that no one should ever invest in a company, no matter how great its products or how crowded its parking lot, without studying its financial statements and estimating its business value.

Unfortunately, most stock buyers have ignored that part.

Barbra Streisand, the day-trading diva, personified the way people abuse Lynch’s teachings. In 1999 she burbled, “We go to Starbucks every day, so I buy Starbucks stock.” But the Funny Girl forgot that no matter how much you love those tall skinny lattes, you still have to analyze Starbucks’s financial statements and make sure the stock isn’t even more overpriced than the coffee. Countless stock buyers made the same mistake by loading up on shares of Amazon.com because they loved the website or buying e*Trade stock because it was their own online broker.

“Experts” gave the idea credence too. In an interview televised on CNN in late 1999, portfolio manager Kevin Landis of the Firsthand Funds was asked plaintively, “How do you do it? Why can’t I do it, Kevin?” (From 1995 through the end of 1999, the Firsthand Technology Value fund produced an astounding 58.2% average annualized gain.) “Well, you can do it,” Landis chirped. “All you really need to do is focus on the things that you know, and stay close to an industry, and talk to people who work in it every day.”2

The most painful perversion of Lynch’s rule occurred in corporate retirement plans. If you’re supposed to “buy what you know,” then what could possibly be a better investment for your 401(k) than your own company’s stock? After all, you work there; don’t you know more about the company than an outsider ever could? Sadly, the employees of Enron, Global Crossing, and WorldCom—many of whom put nearly all their retirement assets in their own company’s stock, only to be wiped out—learned that insiders often possess only the illusion of knowledge, not the real thing.

Psychologists led by Baruch Fischhoff of Carnegie Mellon University have documented a disturbing fact: becoming more familiar with a subject does not significantly reduce people’s tendency to exaggerate how much they actually know about it.3 That’s why “investing in what you know” can be so dangerous; the more you know going in, the less likely you are to probe a stock for weaknesses. This pernicious form of overconfidence is called “home bias,” or the habit of sticking to what is already familiar:

- Individual investors own three times more shares in their local phone company than in all other phone companies combined.

- The typical mutual fund owns stocks whose headquarters are 115 miles closer to the fund’s main office than the average U.S. company is.

- 401(k) investors keep between 25% and 30% of their retirement assets in the stock of their own company.4

In short, familiarity breeds complacency. On the TV news, isn’t it always the neighbor or the best friend or the parent of the criminal who says in a shocked voice, “He was such a nice guy”? That’s because whenever we are too close to someone or something, we take our beliefs for granted, instead of questioning them as we do when we confront something more remote. The more familiar a stock is, the more likely it is to turn a defensive investor into a lazy one who thinks there’s no need to do any homework. Don’t let that happen to you.

Can you Roll Your Own?

Fortunately, for a defensive investor who is willing to do the required homework for assembling a stock portfolio, this is the Golden Age: Never before in financial history has owning stocks been so cheap and convenient.5

Do it yourself. Through specialized online brokerages like www. sharebuilder.com, www.foliofn.com, and www.buyandhold.com, you can buy stocks automatically even if you have very little cash to spare. These websites charge as little as $4 for each periodic purchase of any of the thousands of U.S. stocks they make available. You can invest every week or every month, reinvest the dividends, and even trickle your money into stocks through electronic withdrawals from your bank account or direct deposit from your paycheck. Sharebuilder charges more to sell than to buy—reminding you, like a little whack across the nose with a rolled-up newspaper, that rapid selling is an investing no-no—while FolioFN offers an excellent tax-tracking tool.

Unlike traditional brokers or mutual funds that won’t let you in the door for less than $2,000 or $3,000, these online firms have no minimum account balances and are tailor-made for beginning investors who want to put fledgling portfolios on autopilot. To be sure, a transaction fee of $4 takes a monstrous 8% bite out of a $50 monthly investment—but if that’s all the money you can spare, then these microinvesting sites are the only game in town for building a diversified portfolio.

You can also buy individual stocks straight from the issuing companies. In 1994, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission loosened the handcuffs it had long ago clamped onto the direct sale of stocks to the public. Hundreds of companies responded by creating Internet-based programs allowing investors to buy shares without going through a broker. Some helpful online sources of information on buying stocks directly include www.dripcentral.com, www.netstock direct.com (an affiliate of Sharebuilder), and www.stockpower.com. You may often incur a variety of nuisance fees that can exceed $25 per year. Even so, direct-stock purchase programs are usually cheaper than stockbrokers.

Be warned, however, that buying stocks in tiny increments for years on end can set off big tax headaches. If you are not prepared to keep a permanent and exhaustively detailed record of your purchases, do not buy in the first place. Finally, don’t invest in only one stock—or even just a handful of different stocks. Unless you are not willing to spread your bets, you shouldn’t bet at all. Graham’s guideline of owning between 10 and 30 stocks remains a good starting point for investors who want to pick their own stocks, but you must make sure that you are not overexposed to one industry.6 (For more on how to pick the individual stocks that will make up your portfolio, see pp. 114–115 and Chapters 11, 14, and 15.)

If, after you set up such an online autopilot portfolio, you find yourself trading more than twice a year—or spending more than an hour or two per month, total, on your investments—then something has gone badly wrong. Do not let the ease and up-to-the-minute feel of the Internet seduce you into becoming a speculator. A defensive investor runs—and wins—the race by sitting still.

Get some help. A defensive investor can also own stocks through a discount broker, a financial planner, or a full-service stockbroker. At a discount brokerage, you’ll need to do most of the stock-picking work yourself; Graham’s guidelines will help you create a core portfolio requiring minimal maintenance and offering maximal odds of a steady return. On the other hand, if you cannot spare the time or summon the interest to do it yourself, there’s no reason to feel any shame in hiring someone to pick stocks or mutual funds for you. But there’s one responsibility that you must never delegate. You, and no one but you, must investigate (before you hand over your money) whether an adviser is trustworthy and charges reasonable fees. (For more pointers, see Chapter 10.)

Farm it out. Mutual funds are the ultimate way for a defensive investor to capture the upside of stock ownership without the downside of having to police your own portfolio. At relatively low cost, you can buy a high degree of diversification and convenience—letting a professional pick and watch the stocks for you. In their finest form—index portfolios—mutual funds can require virtually no monitoring or maintenance whatsoever. Index funds are a kind of Rip Van Winkle investment that is highly unlikely to cause any suffering or surprises even if, like Washington Irving’s lazy farmer, you fall asleep for 20 years. They are a defensive investor’s dream come true. For more detail, see Chapter 9.

Filling in the Potholes

As the financial markets heave and crash their way up and down day after day, the defensive investor can take control of the chaos. Your very refusal to be active, your renunciation of any pretended ability to predict the future, can become your most powerful weapons. By putting every investment decision on autopilot, you drop any self-delusion that you know where stocks are headed, and you take away the market’s power to upset you no matter how bizarrely it bounces.

As Graham notes, “dollar-cost averaging” enables you to put a fixed amount of money into an investment at regular intervals. Every week, month, or calendar quarter, you buy more—whether the markets have gone (or are about to go) up, down, or sideways. Any major mutual fund company or brokerage firm can automatically and safely transfer the money electronically for you, so you never have to write a check or feel the conscious pang of payment. It’s all out of sight, out of mind.

The ideal way to dollar-cost average is into a portfolio of index funds, which own every stock or bond worth having. That way, you renounce not only the guessing game of where the market is going but which sectors of the market—and which particular stocks or bonds within them—will do the best.

Let’s say you can spare $500 a month. By owning and dollar-cost averaging into just three index funds—$300 into one that holds the total U.S. stock market, $100 into one that holds foreign stocks, and $100 into one that holds U.S. bonds—you can ensure that you own almost every investment on the planet that’s worth owning.7 Every month, like clockwork, you buy more. If the market has dropped, your preset amount goes further, buying you more shares than the month before. If the market has gone up, then your money buys you fewer shares. By putting your portfolio on permanent autopilot this way, you prevent yourself from either flinging money at the market just when it is seems most alluring (and is actually most dangerous) or refusing to buy more after a market crash has made investments truly cheaper (but seemingly more “risky”).

According to Ibbotson Associates, the leading financial research firm, if you had invested $12,000 in the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index at the beginning of September 1929, 10 years later you would have had only $7,223 left. But if you had started with a paltry $100 and simply invested another $100 every single month, then by August 1939, your money would have grown to $15,571! That’s the power of disciplined buying—even in the face of the Great Depression and the worst bear market of all time.8

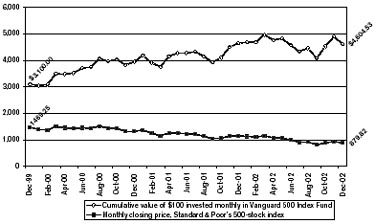

Figure 5-1 shows the magic of dollar-cost averaging in a more recent bear market.

Best of all, once you build a permanent autopilot portfolio with index funds as its heart and core, you’ll be able to answer every market question with the most powerful response a defensive investor could ever have: “I don’t know and I don’t care.” If someone asks whether bonds will outper-forms stocks, just answer, “I don’t know and I don’t care”—after all, you’re automatically buying both. Will health-care stocks make high-tech stocks look sick? “I don’t know and I don’t care”—you’re a permanent owner of both. What’s the next Microsoft? “I don’t know and I don’t care”—as soon as it’s big enough to own, your index fund will have it, and you’ll go along for the ride. Will foreign stocks beat U.S. stocks next year? “I don’t know and I don’t care”—if they do, you’ll capture that gain; if they don’t, you’ll get to buy more at lower prices.

By enabling you to say “I don’t know and I don’t care,” a permanent autopilot portfolio liberates you from the feeling that you need to forecast what the financial markets are about to do—and the illusion that anyone else can. The knowledge of how little you can know about the future, coupled with the acceptance of your ignorance, is a defensive investor’s most powerful weapon.

FIGURE 5-1

Every Little Bit Helps

From the end of 1999 through the end of 2002, the S & P 500-stock average fell relentlessly. But if you had opened an index-fund account with a $3,000 minimum investment and added $100 every month, your total outlay of $6,600 would have lost 30.2%—considerably less than the 41.3% plunge in the market. Better yet, your steady buying at lower prices would build the base for an explosive recovery when the market rebounds.

Source: The Vanguard Group