The “aggressive” investor should start from the same base as the defensive investor, namely, a division of his funds between high-grade bonds and high-grade common stocks bought at reasonable prices.* He will be prepared to branch out into other kinds of security commitments, but in each case he will want a well-reasoned justification for the departure. There is a difficulty in discussing this topic in orderly fashion, because there is no single or ideal pattern for aggressive operations. The field of choice is wide; the selection should depend not only on the individual’s competence and equipment but perhaps equally well upon his interests and preferences.

The most useful generalizations for the enterprising investor are of a negative sort. Let him leave high-grade preferred stocks to corporate buyers. Let him also avoid inferior types of bonds and preferred stocks unless they can be bought at bargain levels—which means ordinarily at prices at least 30% under par for high-coupon issues, and much less for the lower coupons.* He will let someone else buy foreign-government bond issues, even though the yield may be attractive. He will also be wary of all kinds of new issues, including convertible bonds and preferreds that seem quite tempting and common stocks with excellent earnings confined to the recent past.

For standard bond investments the aggressive investor would do well to follow the pattern suggested to his defensive confrere, and make his choice between high-grade taxable issues, which can now be selected to yield about 7¼%, and good-quality tax-free bonds, which yield up to 5.30% on longer maturities.†

Second-Grade Bonds and Preferred Stocks

Since in late-1971 it is possible to find first-rate corporate bonds to yield 7¼%, and even more, it would not make much sense to buy second-grade issues merely for the higher return they offer. In fact corporations with relatively poor credit standing have found it virtually impossible to sell “straight bonds”—i.e., nonconvertibles—to the public in the past two years. Hence their debt financing has been done by the sale of convertible bonds (or bonds with warrants attached), which place them in a separate category. It follows that virtually all the nonconvertible bonds of inferior rating represent older issues which are selling at a large discount. Thus they offer the possibility of a substantial gain in principal value under favorable future conditions—which would mean here a combination of an improved credit rating for the company and lower general interest rates.

But even in the matter of price discounts and resultant chance of principal gain, the second-grade bonds are in competition with better issues. Some of the well-entrenched obligations with “old-style” coupon rates (2½% to 4%) sold at about 50 cents on the dollar in 1970. Examples: American Telephone & Telegraph 2 5/8s, due 1986 sold at 51; Atchison Topeka & Santa Fe RR 4s, due 1995, sold at 51; McGraw-Hill 3 7/8s, due 1992, sold at 50½.

Hence under conditions of late-1971 the enterprising investors can probably get from good-grade bonds selling at a large discount all that he should reasonably desire in the form of both income and chance of appreciation.

Throughout this book we refer to the possibility that any well-defined and protracted market situation of the past may return in the future. Hence we should consider what policy the aggressive investor might have to choose in the bond field if prices and yields of high-grade issues should return to former normals. For this reason we shall reprint here our observations on that point made in the 1965 edition, when high-grade bonds yielded only 4½%.

Something should be said now about investing in second-grade issues, which can readily be found to yield any specified return up to 8% or more. The main difference between first- and second- grade bonds is usually found in the number of times the interest charges have been covered by earnings. Example: In early 1964 Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific 5% income debenture bonds, at 68, yielded 7.35%. But the total interest charges of the road, before income taxes, were earned only 1.5 times in 1963, against our requirement of 5 times for a well-protected railroad issue.1

Many investors buy securities of this kind because they “need income” and cannot get along with the meager return offered by top-grade issues. Experience clearly shows that it is unwise to buy a bond or a preferred which lacks adequate safety merely because the yield is attractive.* (Here the word “merely” implies that the issue is not selling at a large discount and thus does not offer an opportunity for a substantial gain in principal value.) Where such securities are bought at full prices—that is, not many points under 100 * —the chances are very great that at some future time the holder will see much lower quotations. For when bad business comes, or just a bad market, issues of this kind prove highly susceptible to severe sinking spells; often interest or dividends are suspended or at least endangered, and frequently there is a pronounced price weakness even though the operating results are not at all bad.

As a specific illustration of this characteristic of second-quality senior issues, let us summarize the price behavior of a group of ten railroad income bonds in 1946–47. These comprise all of those which sold at 96 or more in 1946, their high prices averaging 102½. By the following year the group had registered low prices averaging only 68, a loss of one-third of the market value in a very short time. Peculiarly enough, the railroads of the country were showing much better earnings in 1947 than in 1946; hence the drastic price decline ran counter to the business picture and was a reflection of the selloff in the general market. But it should be pointed out that the shrinkage in these income bonds was proportionately larger than that in the common stocks in the Dow Jones industrial list (about 23%). Obviously the purchaser of these bonds at a cost above 100 could not have expected to participate to any extent in a further rise in the securities market. The only attractive feature was the income yield, averaging about 4.25% (against 2.50% for first-grade bonds, an advantage of 1.75% in annual income). Yet the sequel showed all too soon and too plainly that for the minor advantage in annual income the buyer of these second-grade bonds was risking the loss of a substantial part of his principal.

The above example permits us to pay our respects to the popular fallacy that goes under the sobriquet of a “businessman’s investment.” That involves the purchase of a security showing a larger yield than is obtainable on a high-grade issue and carrying a correspondingly greater risk. It is bad business to accept an acknowledged possibility of a loss of principal in exchange for a mere 1 or 2% of additional yearly income. If you are willing to assume some risk you should be certain that you can realize a really substantial gain in principal value if things go well. Hence a second-grade 5.5 or 6% bond selling at par is almost always a bad purchase. The same issue at 70 might make more sense—and if you are patient you will probably be able to buy it at that level.

Second-grade bonds and preferred stocks possess two contradictory attributes which the intelligent investor must bear clearly in mind. Nearly all suffer severe sinking spells in bad markets. On the other hand, a large proportion recover their position when favorable conditions return, and these ultimately “work out all right.” This is true even of (cumulative) preferred stocks that fail to pay dividends for many years. There were a number of such issues in the early 1940s, as a consequence of the long depression of the 1930s. During the postwar boom period of 1945–1947 many of these large accumulations were paid off either in cash or in new securities, and the principal was often discharged as well. As a result, large profits were made by people who, a few years previously, had bought these issues when they were friendless and sold at low prices.2

It may well be true that, in an overall accounting, the higher yields obtainable on second-grade senior issues will prove to have offset those principal losses that were irrecoverable. In other words, an investor who bought all such issues at their offering prices might conceivably fare as well, in the long run, as one who limited himself to first-quality securities; or even somewhat better.3

But for practical purposes the question is largely irrelevant. Regardless of the outcome, the buyer of second-grade issues at full prices will be worried and discommoded when their price declines precipitately. Furthermore, he cannot buy enough issues to assure an “average” result, nor is he in a position to set aside a portion of his larger income to offset or “amortize” those principal losses which prove to be permanent. Finally, it is mere common sense to abstain from buying securities at around 100 if long experience indicates that they can probably be bought at 70 or less in the next weak market.

Foreign Government Bonds

All investors with even small experience know that foreign bonds, as a whole, have had a bad investment history since 1914. This was inevitable in the light of two world wars and an intervening world depression of unexampled depth. Yet every few years market conditions are sufficiently favorable to permit the sale of some new foreign issues at a price of about par. This phenomenon tells us a good deal about the working of the average investor’s mind—and not only in the field of bonds.

We have no concrete reason to be concerned about the future history of well-regarded foreign bonds such as those of Australia or Norway. But we do know that, if and when trouble should come, the owner of foreign obligations has no legal or other means of enforcing his claim. Those who bought Republic of Cuba 4½s as high as 117 in 1953 saw them default their interest and then sell as low as 20 cents on the dollar in 1963. The New York Stock Exchange bond list in that year also included Belgian Congo 5¼s at 36, Greek 7s at 30, and various issues of Poland as low as 7. How many readers have any idea of the repeated vicissitudes of the 8% bonds of Czechoslovakia, since they were first offered in this country in 1922 at 96½? They advanced to 112 in 1928, declined to 67 3/4 in 1932, recovered to 106 in 1936, collapsed to 6 in 1939, recovered (unbelievably) to 117 in 1946, fell promptly to 35 in 1948, and sold as low as 8 in 1970!

Years ago an argument of sorts was made for the purchase of foreign bonds here on the grounds that a rich creditor nation such as ours was under moral obligation to lend abroad. Time, which brings so many revenges, now finds us dealing with an intractable balance-of-payments problem of our own, part of which is ascribable to the large-scale purchase of foreign bonds by American investors seeking a small advantage in yield. For many years past we have questioned the inherent attractiveness of such investments from the standpoint of the buyer; perhaps we should add now that the latter would benefit both his country and himself if he declined these opportunities.

New Issues Generally

It might seem ill-advised to attempt any broad statements about new issues as a class, since they cover the widest possible range of quality and attractiveness. Certainly there will be exceptions to any suggested rule. Our one recommendation is that all investors should be wary of new issues—which means, simply, that these should be subjected to careful examination and unusually severe tests before they are purchased.

There are two reasons for this double caveat. The first is that new issues have special salesmanship behind them, which calls therefore for a special degree of sales resistance.* The second is that most new issues are sold under “favorable market conditions”—which means favorable for the seller and consequently less favorable for the buyer.†

The effect of these considerations becomes steadily more important as we go down the scale from the highest-quality bonds through second-grade senior issues to common-stock flotations at the bottom. A tremendous amount of financing, consisting of the repayment of existing bonds at call price and their replacement by new issues with lower coupons, was done in the past. Most of this was in the category of high-grade bonds and preferred stocks. The buyers were largely financial institutions, amply qualified to protect their interests. Hence these offerings were carefully priced to meet the going rate for comparable issues, and high-powered salesmanship had little effect on the outcome. As interest rates fell lower and lower the buyers finally came to pay too high a price for these issues, and many of them later declined appreciably in the market. This is one aspect of the general tendency to sell new securities of all types when conditions are most favorable to the issuer; but in the case of first-quality issues the ill effects to the purchaser are likely to be unpleasant rather than serious.

The situation proves somewhat different when we study the lower-grade bonds and preferred stocks sold during the 1945–46 and 1960–61 periods. Here the effect of the selling effort is more apparent, because most of these issues were probably placed with individual and inexpert investors. It was characteristic of these offerings that they did not make an adequate showing when judged by the performance of the companies over a sufficient number of years. They did look safe enough, for the most part, if it could be assumed that the recent earnings would continue without a serious setback. The investment bankers who brought out these issues presumably accepted this assumption, and their salesmen had little difficulty in persuading themselves and their customers to a like effect. Nevertheless it was an unsound approach to investment, and one likely to prove costly.

Bull-market periods are usually characterized by the transformation of a large number of privately owned businesses into companies with quoted shares. This was the case in 1945–46 and again beginning in 1960. The process then reached extraordinary proportions until brought to a catastrophic close in May 1962. After the usual “swearing-off” period of several years the whole tragicomedy was repeated, step by step, in 1967–1969.*

New Common-Stock Offerings

The following paragraphs are reproduced unchanged from the 1959 edition, with comment added:

Common-stock financing takes two different forms. In the case of companies already listed, additional shares are offered pro rata to the existing stockholders. The subscription price is set below the current market, and the “rights” to subscribe have an initial money value.* The sale of the new shares is almost always under-written by one or more investment banking houses, but it is the general hope and expectation that all the new shares will be taken by the exercise of the subscription rights. Thus the sale of additional common stock of listed companies does not ordinarily call for active selling effort on the part of distributing firms.

The second type is the placement with the public of common stock of what were formerly privately owned enterprises. Most of this stock is sold for the account of the controlling interests to enable them to cash in on a favorable market and to diversify their own finances. (When new money is raised for the business it comes often via the sale of preferred stock, as previously noted.) This activity follows a well-defined pattern, which by the nature of the security markets must bring many losses and disappointments to the public. The dangers arise both from the character of the businesses that are thus financed and from the market conditions that make the financing possible.

In the early part of the century a large proportion of our leading companies were introduced to public trading. As time went on, the number of enterprises of first rank that remained closely held steadily diminished; hence original common-stock flotations have tended to be concentrated more and more on relatively small concerns. By an unfortunate correlation, during the same period the stock-buying public has been developing an ingrained preference for the major companies and a similar prejudice against the minor ones. This prejudice, like many others, tends to become weaker as bull markets are built up; the large and quick profits shown by common stocks as a whole are sufficient to dull the public’s critical faculty, just as they sharpen its acquisitive instinct. During these periods, also, quite a number of privately owned concerns can be found that are enjoying excellent results—although most of these would not present too impressive a record if the figures were carried back, say, ten years or more.

When these factors are put together the following consequences emerge: Somewhere in the middle of the bull market the first common-stock flotations make their appearance. These are priced not unattractively, and some large profits are made by the buyers of the early issues. As the market rise continues, this brand of financing grows more frequent; the quality of the companies becomes steadily poorer; the prices asked and obtained verge on the exorbitant. One fairly dependable sign of the approaching end of a bull swing is the fact that new common stocks of small and nondescript companies are offered at prices somewhat higher than the current level for many medium-sized companies with a long market history. (It should be added that very little of this common-stock financing is ordinarily done by banking houses of prime size and reputation.)*

The heedlessness of the public and the willingness of selling organizations to sell whatever may be profitably sold can have only one result—price collapse. In many cases the new issues lose 75% and more of their offering price. The situation is worsened by the aforementioned fact that, at bottom, the public has a real aversion to the very kind of small issue that it bought so readily in its careless moments. Many of these issues fall, proportionately, as much below their true value as they formerly sold above it.

An elementary requirement for the intelligent investor is an ability to resist the blandishments of salesmen offering new common-stock issues during bull markets. Even if one or two can be found that can pass severe tests of quality and value, it is probably bad policy to get mixed up in this sort of business. Of course the salesman will point to many such issues which have had good-sized market advances—including some that go up spectacularly the very day they are sold. But all this is part of the speculative atmosphere. It is easy money. For every dollar you make in this way you will be lucky if you end up by losing only two.

Some of these issues may prove excellent buys—a few years later, when nobody wants them and they can be had at a small fraction of their true worth.

In the 1965 edition we continued our discussion of this subject as follows:

While the broader aspects of the stock market’s behavior since 1949 have not lent themselves well to analysis based on long experience, the development of new common-stock flotations proceeded exactly in accordance with ancient prescription. It is doubtful whether we ever before had so many new issues offered, of such low quality, and with such extreme price collapses, as we experienced in 1960–1962.4 The ability of the stock market as a whole to disengage itself rapidly from that disaster is indeed an extraordinary phenomenon, bringing back long-buried memories of the similar invulnerability it showed to the great Florida real-estate collapse in 1925.

Must there be a return of the new-stock-offering madness before the present bull market can come to its definitive close? Who knows? But we do know that an intelligent investor will not forget what happened in 1962 and will let others make the next batch of quick profits in this area and experience the consequent harrowing losses.

We followed these paragraphs in the 1965 edition by citing “A Horrible Example,” namely, the sale of stock of Aetna Maintenance Co. at $9 in November 1961. In typical fashion the shares promptly advanced to $15; the next year they fell to 2 3/8, and in 1964 to 7/8. The later history of this company was on the extraordinary side, and illustrates some of the strange metamorphoses that have taken place in American business, great and small, in recent years. The curious reader will find the older and newer history of this enterprise in Appendix 5.

It is by no means difficult to provide even more harrowing examples taken from the more recent version of “the same old story,” which covered the years 1967–1970. Nothing could be more pat to our purpose than the case of AAA Enterprises, which happens to be the first company then listed in Standard & Poor’s Stock Guide. The shares were sold to the public at $14 in 1968, promptly advanced to 28, but in early 1971 were quoted at a dismal 25¢. (Even this price represented a gross overvaluation of the enterprise, since it had just entered the bankruptcy court in a hopeless condition.) There is so much to be learned, and such important warnings to be gleaned, from the story of this flotation that we have reserved it for detailed treatment below, in Chapter 17.

Commentary on Chapter 6

The punches you miss are the ones that wear you out.

—Boxing trainer Angelo Dundee

For the aggressive as well as the defensive investor, what you don’t do is as important to your success as what you do. In this chapter, Graham lists his “don’ts” for aggressive investors. Here is a list for today.

Junkyard Dogs?

High-yield bonds—which Graham calls “second-grade” or “lower-grade” and today are called “junk bonds”—get a brisk thumbs-down from Graham. In his day, it was too costly and cumbersome for an individual investor to diversify away the risks of default.;1 (To learn how bad a default can be, and how carelessly even “sophisticated” professional bond investors can buy into one, see the sidebar on p. 146.) Today, however, more than 130 mutual funds specialize in junk bonds. These funds buy junk by the cartload; they hold dozens of different bonds. That mitigates Graham’s complaints about the difficulty of diversifying. (However, his bias against high-yield preferred stock remains valid, since there remains no cheap and widely available way to spread their risks.)

Since 1978, an annual average of 4.4% of the junk-bond market has gone into default—but, even after those defaults, junk bonds have still produced an annualized return of 10.5%, versus 8.6% for 10-year U.S. Treasury bonds.2 Unfortunately, most junk-bond funds charge high fees and do a poor job of preserving the original principal amount of your investment. A junk fund could be appropriate if you are retired, are looking for extra monthly income to supplement your pension, and can tolerate temporary tumbles in value. If you work at a bank or other financial company, a sharp rise in interest rates could limit your raise or even threaten your job security—so a junk fund, which tends to outper-forms most other bond funds when interest rates rise, might make sense as a counterweight in your 401(k). A junk-bond fund, though, is only a minor option—not an obligation—for the intelligent investor.

A WORLD OF HURT FOR WORLDCOM BONDS

Buying a bond only for its yield is like getting married only for the sex. If the thing that attracted you in the first place dries up, you’ll find yourself asking, “What else is there?” When the answer is “Nothing,” spouses and bondholders alike end up with broken hearts.

On May 9, 2001, WorldCom, Inc. sold the biggest offering of bonds in U.S. corporate history—$11.9 billion worth. Among the eager beavers attracted by the yields of up to 8.3% were the California Public Employees’ Retirement System, one of the world’s largest pension funds; Retirement Systems of Alabama, whose managers later explained that “the higher yields” were “very attractive to us at the time they were purchased”; and the Strong Corporate Bond Fund, whose comanager was so fond of WorldCom’s fat yield that he boasted, “we’re getting paid more than enough extra income for the risk.” 1

But even a 30-second glance at WorldCom’s bond prospectus would have shown that these bonds had nothing to offer but their yield—and everything to lose. In two of the previous five years WorldCom’s pretax income (the company’s profits before it paid its dues to the IRS) fell short of covering its fixed charges (the costs of paying interest to its bondholders) by a stupendous $4.1 billion. WorldCom could cover those bond payments only by borrowing more money from banks. And now, with this mountainous new helping of bonds, WorldCom was fattening its interest costs by another $900 million per year!2 Like Mr. Creosote in Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life, WorldCom was gorging itself to the bursting point.

No yield could ever be high enough to compensate an investor for risking that kind of explosion. The WorldCom bonds did produce fat yields of up to 8% for a few months. Then, as Graham would have predicted, the yield suddenly offered no shelter:

- WorldCom filed bankruptcy in July 2002.

- WorldCom admitted in August 2002 that it had overstated its earnings by more than $7 billion.3

- WorldCom’s bonds defaulted when the company could no longer cover their interest charges; the bonds lost more than 80% of their original value.

The Vodka-and-Burrito Portfolio

Graham considered foreign bonds no better a bet than junk bonds.3Today, however, one variety of foreign bond may have some appeal for investors who can withstand plenty of risk. Roughly a dozen mutual funds specialize in bonds issued in emerging-market nations (or what used to be called “Third World countries”) like Brazil, Mexico, Nigeria, Russia, and Venezuela. No sane investor would put more than 10% of a total bond portfolio in spicy holdings like these. But emerging-markets bond funds seldom move in synch with the U.S. stock market, so they are one of the rare investments that are unlikely to drop merely because the Dow is down. That can give you a small corner of comfort in your portfolio just when you may need it most.4

Dying a Trader’s Death

As we’ve already seen in Chapter 1, day trading—holding stocks for a few hours at a time—is one of the best weapons ever invented for committing financial suicide. Some of your trades might make money, most of your trades will lose money, but your broker will always make money.

And your own eagerness to buy or sell a stock can lower your return. Someone who is desperate to buy a stock can easily end up having to bid 10 cents higher than the most recent share price before any sellers will be willing to part with it. That extra cost, called “market impact,” never shows up on your brokerage statement, but it’s real. If you’re overeager to buy 1,000 shares of a stock and you drive its price up by just five cents, you’ve just cost yourself an invisible but very real $50. On the flip side, when panicky investors are frantic to sell a stock and they dump it for less than the most recent price, market impact hits home again.

The costs of trading wear away your returns like so many swipes of sandpaper. Buying or selling a hot little stock can cost 2% to 4% (or 4% to 8% for a “round-trip” buy-and-sell transaction).5 If you put $1,000 into a stock, your trading costs could eat up roughly $40 before you even get started. Sell the stock, and you could fork over another 4% in trading expenses.

Oh, yes—there’s one other thing. When you trade instead of invest, you turn long-term gains (taxed at a maximum capital-gains rate of 20%) into ordinary income (taxed at a maximum rate of 38.6%).

Add it all up, and a stock trader needs to gain at least 10% just to break even on buying and selling a stock.6 Anyone can do that once, by luck alone. To do it often enough to justify the obsessive attention it requires—plus the nightmarish stress it generates—is impossible.

Thousands of people have tried, and the evidence is clear: The more you trade, the less you keep.

Finance professors Brad Barber and Terrance Odean of the University of California examined the trading records of more than 66,000 customers of a major discount brokerage firm. From 1991 through 1996, these clients made more than 1.9 million trades. Before the costs of trading sandpapered away at their returns, the people in the study actually outperformed the market by an average of at least half a percentage point per year. But after trading costs, the most active of these traders—who shifted more than 20% of their stock holdings per month—went from beating the market to underperforming it by an abysmal 6.4 percentage points per year. The most patient investors, however—who traded a minuscule 0.2% of their total holdings in an average month—managed to outper-forms the market by a whisker, even after their trading costs. Instead of giving a huge hunk of their gains away to their brokers and the IRS, they got to keep almost everything.7 For a look at these results, see Figure 6-1.

The lesson is clear: Don’t just do something, stand there. It’s time for everyone to acknowledge that the term “long-term investor” is redundant. A long-term investor is the only kind of investor there is. Someone who can’t hold on to stocks for more than a few months at a time is doomed to end up not as a victor but as a victim.

The Early Bird Gets Wormed

Among the get-rich-quick toxins that poisoned the mind of the investing public in the 1990s, one of the most lethal was the idea that you can build wealth by buying IPOs. An IPO is an “initial public offering,” or the first sale of a company’s stock to the public. At first blush, investing in IPOs sounds like a great idea—after all, if you’d bought 100 shares of Microsoft when it went public on March 13, 1986, your $2,100 investment would have grown to $720,000 by early 2003.8And finance professors Jay Ritter and William Schwert have shown that if you had spread a total of only $1,000 across every IPO in January 1960, at its offering price, sold out at the end of that month, then invested anew in each successive month’s crop of IPOs, your portfolio would have been worth more than $533 decillion by year-end 2001.

(On the printed page, that looks like this: $533,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000.)

FIGURE 6-1

The Faster You Run, the Behinder You Get

Researchers Brad Barber and Terrance Odean divided thousands of traders into five tiers based on how often they turned over their holdings. Those who traded the least (at the left) kept most of their gains. But the impatient and hyperactive traders made their brokers rich, not themselves. (The bars at the far right show a market index fund for comparison.)

Source: Profs. Brad Barber, University of California at Davis, and Terrance Odean, University of California at Berkeley

Unfortunately, for every IPO like Microsoft that turns out to be a big winner, there are thousands of losers. The psychologists Daniel Kahnerman and Amos Tversky have shown when humans estimate the likelihood or frequency of an event, we make that judgment based not on how often the event has actually occurred, but on how vivid the past examples are. We all want to buy “the next Microsoft”—precisely because we know we missed buying the first Microsoft. But we conveniently overlook the fact that most other IPOs were terrible investments. You could have earned that $533 decillion gain only if you never missed a single one of the IPO market’s rare winners—a practical impossibility. Finally, most of the high returns on IPOs are captured by members of an exclusive private club—the big investment banks and fund houses that get shares at the initial (or “underwriting”) price, before the stock begins public trading. The biggest “run-ups” often occur in stocks so small that even many big investors can’t get any shares; there just aren’t enough to go around.

If, like nearly every investor, you can get access to IPOs only after their shares have rocketed above the exclusive initial price, your results will be terrible. From 1980 through 2001, if you had bought the average IPO at its first public closing price and held on for three years, you would have underperformed the market by more than 23 percentage points annually.9

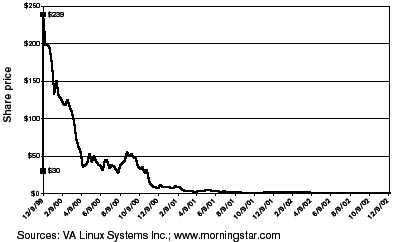

Perhaps no stock personifies the pipe dream of getting rich from IPOs better than VA Linux. “LNUX THE NEXT MSFT,” exulted an early owner; “BUY NOW, AND RETIRE IN FIVE YEARS FROM NOW.”10 On December 9, 1999, the stock was placed at an initial public offering price of $30. But demand for the shares was so ferocious that when NASDAQ opened that morning, none of the initial owners of VA Linux would let go of any shares until the price hit $299. The stock peaked at $320 and closed at $239.25, a gain of 697.5% in a single day. But that gain was earned by only a handful of institutional traders; individual investors were almost entirely frozen out.

More important, buying IPOs is a bad idea because it flagrantly violates one of Graham’s most fundamental rules: No matter how many other people want to buy a stock, you should buy only if the stock is a cheap way to own a desirable business. At the peak price on day one, investors were valuing VA Linux’s shares at a total of $12.7 billion. What was the company’s business worth? Less than five years old, VA Linux had sold a cumulative total of $44 million worth of its software and services—but had lost $25 million in the process. In its most recent fiscal quarter, VA Linux had generated $15 million in sales but had lost $10 million on them. This business, then, was losing almost 70 cents on every dollar it took in. VA Linux’s accumulated deficit (the amount by which its total expenses had exceeded its income) was $30 million.

If VA Linux were a private company owned by the guy who lives next door, and he leaned over the picket fence and asked you how much you would pay to take his struggling little business off his hands, would you answer, “Oh, $12.7 billion sounds about right to me”? Or would you, instead, smile politely, turn back to your barbecue grill, and wonder what on earth your neighbor had been smoking? Relying exclusively on our own judgment, none of us would be caught dead agreeing to pay nearly $13 billion for a money-loser that was already $30 million in the hole.

But when we’re in public instead of in private, when valuation suddenly becomes a popularity contest, the price of a stock seems more important than the value of the business it represents. As long as someone else will pay even more than you did for a stock, why does it matter what the business is worth?

This chart shows why it matters.

FIGURE 6-2

The Legend of VA Linux

After going up like a bottle rocket on that first day of trading, VA Linux came down like a buttered brick. By December 9, 2002, three years to the day after the stock was at $239.50, VA Linux closed at $1.19 per share.

Weighing the evidence objectively, the intelligent investor should conclude that IPO does not stand only for “initial public offering.” More accurately, it is also shorthand for:

It’s Probably Overpriced,

Imaginary Profits Only,

Insiders’ Private Opportunity, or

Idiotic, Preposterous, and Outrageous.