Chapter 5

Derivatives

Derivative instruments (also known as derivative contracts) are financial contracts whose value depends upon the value of an underlying instrument or asset (typically a commodity, bond, equity or currency, or a combination of these).

There are two main classes of derivative contracts – exchange traded derivatives and OTC (over the counter) derivatives.

5.1 EXCHANGE TRADED DERIVATIVE CONTRACTS

As the name implies, these contracts are devised by and traded on investment exchanges, such as the Euronext.LIFFE exchange in London, the Chicago Board of Trade and the Eurex exchange in Frankfurt. These exchanges devise, standardise and provide trading facilities or a wide range of futures and options based on underlying instruments such as exchange rates, interest rates, government bonds, equity indexes, individual equities, as well as commodities such as wheat, copper and oil.

Exchanges provide two forms of derivative contracts – traded options and futures.

5.1.1 Traded options

There are two forms of traded options – put options and call options. A call option gives the buyer (or holder) the right (but not the obligation) to purchase the underlying instrument at a specified price (known as the strike price) on or before a given date known as the exercise date. A put option on the other hand gives the buyer (or holder) the right (but not the obligation) to sell the underlying instrument at a specified price on or before a given date. In order to acquire the rights to buy or sell the instrument at the agreed strike price the investor pays an option premium.

An investor that expects the price of a particular underlying instrument to rise in the near future will buy a call option while an investor that expects the price to fall would buy a put option.

Example

The price of Vodafone plc shares on 5 February 2008 on the London Stock Exchange is 164.4 pence per share. The Euronext.LIFFE exchange offers a variety of put and call options on Vodafone shares at different strike prices and exercise dates.

Investor A expects that the price will rise to 220 pence by June 2008. He therefore buys 10 lots1 of the Euronext.LIFFE call option for June 2008 with a strike price of 200 pence. The option premium he pays is 5.25 pence per share.

He therefore pays a premium of (£.0525 + 10 lots * 1000 shares) £525.00. If, by the end of June, the price of Vodafone shares fails to reach 200 pence then he will allow the option to expire, and will lose £525.00. Alternatively, if the price is greater than 200 pence he could either exercise his option and purchase the shares at 200 pence each, or sell the option to another investor on the exchange.

If the price of the share had risen to 220 pence by the exercise date, and the investor did exercise the option and then sell the shares he had acquired, then the net result (exclusive of any commissions and expenses) would be:

| Sale proceeds of 10 000 Vodafone plc @ £2.20 per share | £22 000.00 |

| Less: cost of shares | £20 000.00 |

| Less: exercise price of option | £525.00 |

| Gross profit | £1475.00 |

Conversely, if the investor expected the price of Vodafone shares to fall below the current level of 164.4 pence, he could have purchased a put option at a lower price.

Investors that hold a long position in a particular underlying instrument often buy put options as a form of insurance against a fall in the price of the underlying instrument; while investors that hold a short position in the underlying often buy call options as a form of insurance against a rise in the price. This form of insurance is known as hedging.

Listed options may be either European style or American style:

- A European style option may be exercised only at the expiry date of the option, i.e. at a single pre-defined point in time.

- An American style option may be exercised at any time before the expiry date.

5.1.2 Exchange traded futures

A futures contract is a legally binding agreement to buy or sell a commodity or financial instrument in a designated future month at a price agreed upon today by the buyer and seller. Futures contracts are standardised according to the quality, quantity and delivery time and location for each commodity. A futures contract differs from an option because an option is the right to buy or sell, while a futures contract is the promise to actually make a transaction. Futures contracts, like options contracts, are used in hedging.

Example – the Eurex Bund Futures contract

Eurex’s fixed income derivatives are the benchmark for the European yield curve and often serve as a standard reference when comparing, evaluating and hedging interest rates in Europe.

The Euro-Bund Futures allow investors to enter positions based on interest rate movements. Investors are able to use these products to take relative value positions between different maturity ranges or market segments as well as to arbitrage between the cash and futures markets. In other words, an investor who expects interest rates to rise in the future, and therefore the price of his existing bond portfolio to fall, will sell Bund Futures at today’s price. Conversely, an investor who has a short position in his bond portfolio and expects interest rates to fall will buy Bund Futures at today’s price.

Contract specifications – the Eurex Bund Futures contract

Euro-Bund Futures are based on a notional long-term debt instrument with a term of 8.5 to 10.5 years, bearing a notional coupon rate of 6% and are based on debt instruments issued by the Federal Republic of Germany. One lot of Euro-Bund Futures has a contract value of EUR 100 000 and minimum price changes of 0.01% – equivalent to a value of EUR 10.

There are contracts available for the three successive quarterly months within the March, June, September and December cycle. The delivery date is the tenth calendar day of the respective quarterly month, if this day is a working day; otherwise the following working day.

Trading volume

Eurex’s Euro-Bund (FGBL), Euro-Bobl (FGBM) and Euro-Schatz (FGBS) Futures are the world’s most heavily traded fixed income futures. The most actively traded product among them, the Euro-Bund Future, had a daily average volume of approximately one million lots during 2004.

Trade computations for the Bund contract

As one lot of Bund Futures is based on EUR 100 000 of the underlying government bond, then if an investor purchases 10 lots of the Mach contract at 108.64 the computation is:

![]()

No money actually changes hands when a futures contract is purchased or sold. Instead, the investor deposits collateral with a clearing house nominated by the exchange concerned. The mechanics of this will be dealt with in section 7.7 and section 19.3.

5.2 MORE TRADE TERMINOLOGY

We now have some further trade terms from the exchange traded derivative transactions (Table 5.1) to add to those that we have gathered from examining equity, bond and cash trades.

Table 5.1 Listed derivative trade terminology

| Term | Explanation |

| Lot | The size of a futures or options trade is measured in lots. One lot represents a given amount of the underlying instrument, and the value of one lot is specified by the exchange that lists the contract |

| Exercise price | The price (of the underlying instrument) at which an option may be exercised |

| Exercise date | The latest date on which an option may be exercised. After this date the option expires and has no value |

| Strike price | See exercise price |

| Option Premium | The amount that the investor pays for the right to acquire an option |

| Underlying | The instrument on which a future or option is based |

5.3 OTC DERIVATIVES

As well as listed futures and options there is a very wide variety of derivative contracts that are traded between investors and financial institutions without using an exchange. These include, inter alia:

- Interest rate swaps

- Currency swaps

- Credit default swaps

- Equity and equity index swaps

- Forward rate agreements

- Caps, collars and floors

- Credit default swaps

- OTC options.

It is beyond the scope of this book to provide a detailed explanation of all these contract types; see Appendix 3 for a list of publications that will provide further information. The book does examine interest rate swaps and currency swaps in detail, first, because an understanding of these instruments is the starting point for understanding most of the others, and second, because the size of the market for these instruments is huge – in 2006, the International Swaps and Derivatives Association estimated that the value of the outstanding contracts in these instruments was USD 285 728.14 billion. We shall also describe the other forms of OTC derivatives in brief.

5.3.1 Interest rate swaps

The essence of the transaction is that two parties agree to exchange (or swap) the cash flows from two payment streams. For example, a high street bank that takes retail deposits from customers at a variable rate of interest and wishes to provide fixed rate mortgages to other customers might “swap” the variable rate cash flows from its borrowings with another institution that has the opposite problem – it has fixed rate deposits but needs to make variable rate loans. In this way, the two institutions protect themselves from adverse movements in short-term interest rates.

Example

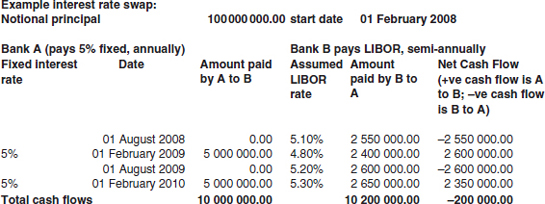

Bank A wishes to swap a notional principal of USD 100 000 000.00 with Bank B for two years from 1 February 2008 till 1 February 2010. Bank A will pay Bank B fixed interest of 5% annually on the notional principal while Bank B will pay Bank A interest at LIBOR semi-annually. LIBOR rates will not be fixed until two days before each interest period, so we are unable to predict the actual payments that B will need to make to A at the start date of the transaction.

Making some assumptions as to the actual LIBOR rates for the two years, the cash flows that the two institutions exchange will be as shown in Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1 Example of an interest rate swap

Note the following practical issues about the exchanges of cash flows:

- At no time do A and B exchange the principal – there would be no point in doing so, as they would both pay each other the same amount.

- At each interest payment date, the two cash flows are netted, and only one bank has a payment to make on each date. This is to avoid delivery risk – the risk that one payment is made correctly but the other cannot be made for any reason.

Alternative forms of interest rate swap

The interest rate swap in the above example can be considered a “classic” swap, in that the two parties are swapping a stream of fixed interest payments for a stream of floating rate interest payments. These types of swap are also known as “coupon swaps” where the term coupon is derived from the name of the interest payment on debt instruments. One of the common variations is basis swaps, where the two parties exchange two streams of payments that are based on benchmark interest rates. For example, they may swap a series of cash flows based on different tenors of the same benchmark (e.g. three-month LIBOR for six-month LIBOR), or they may swap different benchmarks (e.g. six-month LIBOR for six-month EURIBOR).

Currency swaps

A currency swap occurs when two parties exchange two payment streams in different currencies, calculated at a different interest rate, and also agree to return the original principal amount to each other at an exchange rate agreed at the start of the contract.

Example

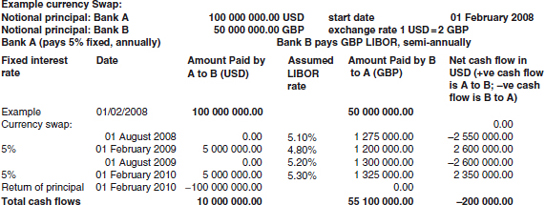

On trade date 29 January 2008 the USD/GBP exchange rate is 2.00.

Banks A and B agree to swap the 5% fixed rate income streams on USD 100 000 00 with the floating rate LIBOR income streams on GBP 50 000 000 for two years from 1 February 2008. Bank A pays Bank B USD at 5%, while Bank B pays Bank A GBP LIBOR.

Making some assumptions as to the actual LIBOR rates for the two years, the cash flows that the two institutions exchange will be as shown in Figure 5.2.

Figure 5.2 Example of a currency swap

Unlike interest rate swaps, the principal amount of the transaction is exchanged at the start of the transaction, and returned at the end. The interest payments cannot be netted off against each other as they are denominated in different currencies.

5.3.2 Other OTC derivatives in brief

Credit default swaps

A credit default swap (CDS) is a contract under which two trade parties agree to isolate and separately trade the credit risk of one or more securities or other obligations issued by a third party.

Under a credit default swap agreement, a protection buyer pays a periodic fee to a protection seller in exchange for a contingent payment by the seller upon a credit event (such as a default or failure to pay) happening to the underlying securities. When a credit event is triggered, the protection seller either takes delivery of the defaulted security for the par value (physical settlement) or pays the protection buyer the difference between the par value and recovery value of the bond (cash settlement).

Credit default swaps resemble an insurance policy, as they can be used by debt owners to hedge against credit events. However, because there is no requirement to actually hold any asset or suffer a loss, credit default swaps can be used to speculate on changes in credit spread.

Credit default swaps are the most widely traded credit derivative product. The typical term of a credit default swap contract is five years, although being an over-the-counter derivative, credit default swaps of almost any maturity can be traded.

Equity and equity index swaps

An equity swap is where one of the payment streams is based on the return from holding an equity or equity index instead of being based on an interest rate.

For example, Party A swaps £5 000 000 at LIBOR + 0.03% against £5000000 exposure to the FTSE100 index with Party B for six months.

Party A receives from Party B any percentage increase in the FTSE applied to the £5000000 notional; while Party B receives interest paid at LIBOR + 0.03% from Party A.

If the FTSE at the six-month mark had risen by 10% from its level at trade commencement, the equity payer/floating leg receiver (Party B) would owe 10% * £5 000 000 = £500 000 to the floating leg payer/equity receiver (Party A). If, on the other hand, the FTSE at the six-month mark had fallen by 10% from its level at trade commencement, the equity receiver/floating leg payer (Party A) would owe an additional 10% * £5 000 000 = £500 000 to the floating leg receiver/equity payer (Party B).

Equity contracts for difference

A contract for difference (CFD) is a contract between two parties, buyer and seller, stipulating that the seller will pay to the buyer the difference between the current value of an equity and its value at a future date. If the difference is negative, then the buyer pays to the seller. CFDs allow investors to speculate on share price movements without the need for ownership of the underlying shares.

Contracts for differences allow investors to take long or short positions, and unlike futures contracts have no fixed expiry date or contract size. CFDs are often used by UK investors to gain exposure to the growth potential of an individual equity without the requirement to pay stamp duty.

Forward rate agreements

A forward rate agreement (FRA) can be thought of as a mini-swap, with only one interest payment date instead of many. It is a forward contract in which one party pays a fixed interest rate, and receives a floating interest rate equal to a reference rate (the underlying rate). The payments are calculated over a notional amount over a certain period, and netted, i.e. only the differential is paid. It is paid on the effective date. The reference rate is fixed at zero, one or two days before the termination date, dependent on the market convention for the particular currency. A swap is a combination of FRAs.

The payer of the fixed interest rate is also known as the borrower or the buyer, while the receiver of the fixed interest rate is the lender or the seller.

Caps, collars and floors

An interest rate cap is a contract where the buyer receives money at the end of each period in which an interest rate exceeds the agreed strike price. An example of a cap would be an agreement to receive money for each month the LIBOR rate exceeds 5%.

An interest rate floor is a contract where the buyer of the floor receives money at the end of each period in which an interest rate is lower than the agreed strike price. An example of a cap would be an agreement to receive money for each month the LIBOR rate is lower than 2.5%.

When a firm buys both an interest rate cap and an interest rate floor on the same index, it is known as a collar.

OTC options

As well as the traded (or listed) options that are traded on exchanges, there is also a large OTC market in put and call options based on a wide variety of underlying instruments.

The OTC option market enables firms to write and purchase put and call options on instruments that it would be uneconomic for exchanges to list, and at wider variety of strike prices and exercise dates than the exchanges could list. Trade parties benefit from avoiding the restrictions that exchanges place on options. The flexibility allows participants to achieve their desired position more precisely and cost effectively. However, the market for some of these options is far less liquid than its exchange traded equivalent.

Note that when an investor writes an option, its income is fixed but its downside risk is unlimited. For example, if an investor writes a call option on a share that is currently trading at £10 and receives a premium of £1 per share for doing so, then, if the buyer decides to exercise the option, the writer has to purchase the shares for the investor. At the time the option is exercised the share price could be £11, £15 or even higher – it is not predictable; but the maximum income that the writer will receive is the option premium of £1 per share.

More trade terminology

We now have some further trade terms from the OTC derivative transactions (Table 5.2) to add to those that we have gathered from examining equity, bond, cash and exchange trade derivative trades.

Table 5.2 OTC derivative trade terminology

| Term | Explanation |

| Notional principal | The principal amount of a swap trade |

1 Exchange traded derivatives are traded in “lots”. One lot is the minimum size of a trade on the exchange. Euronext has defined one lot in the context of Vodafone options as being equivalent to 1000 Vodafone shares.