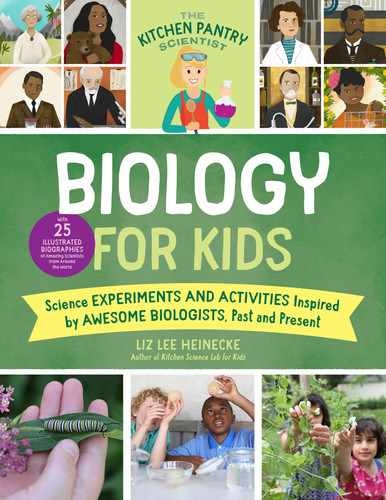

LAB 15

LAB 15

Ynés Mexía b. 1870

PLANT COLLECTION/IDENTIFICATION

NATURE-LOVER

Ynés Enriquetta Juliette Mexía was born in 1870 in Washington D.C. Her father was a Mexican diplomat, and when her parents divorced, she moved to Texas with her mother. No matter where she was, whether it was Texas or Mexico, she loved taking long walks and studying the birds and plants she encountered. As a young woman, Ynés wasn’t able to attend college, but even as an adult, she remained interested in the natural world.

CALIFORNIA

In 1909, Ynés moved to San Francisco, California. After experiencing personal tragedies, she was mentally and physically exhausted, but she found comfort in the beautiful mountains and redwood trees of Northern California. She became an active member the Sierra Club, which the naturalist John Muir had helped establish in 1892 to preserve Yosemite National Park, and she eventually took classes at the University of California–Berkeley.

SLEEPING UNDER THE STARS

Ynés was fifty-one when she started taking classes at Berkeley, and she went on her first major plant-collecting expeditions to in 1925, when she was fifty-five. Ignoring the male explorers who said that it would be impossible for a woman to travel alone in South America, she continued taking trips up and down the Americas, wearing pants, riding horses, and sleeping under the stars. She survived an earthquake, poisonous berries, and extremely difficult conditions on her quest to discover new species and document especially interesting plants, such as the wax palm tree, which could grow up to 200 feet (61 m) tall. Ynés Mexía joined other expeditions as well, including one to Brazil headed by Agnes Chase (Lab 12) and her colleague A. S. Hitchcock. Her assistant, Nina Floy Bracelin, prepared and helped identify the plants Ynés collected.

A SCIENCE COMMUNICATOR

Although Ynés Mexía was so busy collecting plants that she never finished her college degree, she gathered almost 150,000 species. In thirteen short years, Ynés discovered 500 new plant species and 2 new genera. Between expeditions, she gave lectures in San Francisco, sharing photographs of her journeys and teaching people about plants. Ynés suffered from prejudice because of her Mexican heritage, her age, and her gender, but everyone who knew her said that she was friendly, unassuming, and tough. She died in 1938 in Berkeley, California.

IN TODAY’S WORLD

Today, specimens collected by Ynés Mexía can be found in museums from New York to San Francisco.

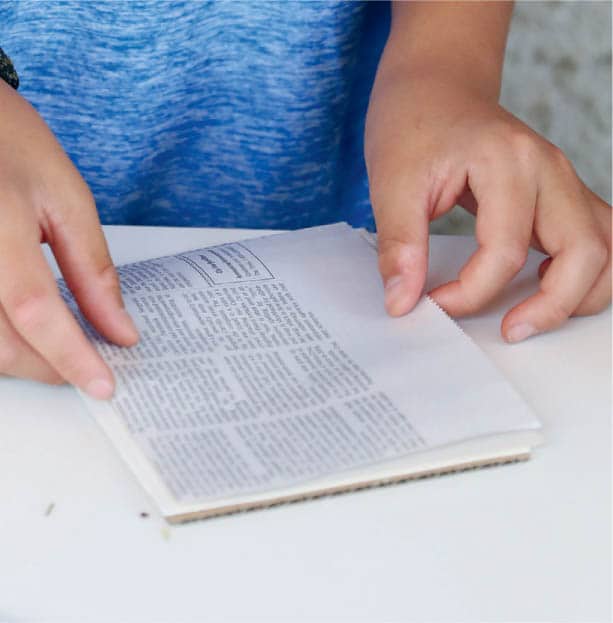

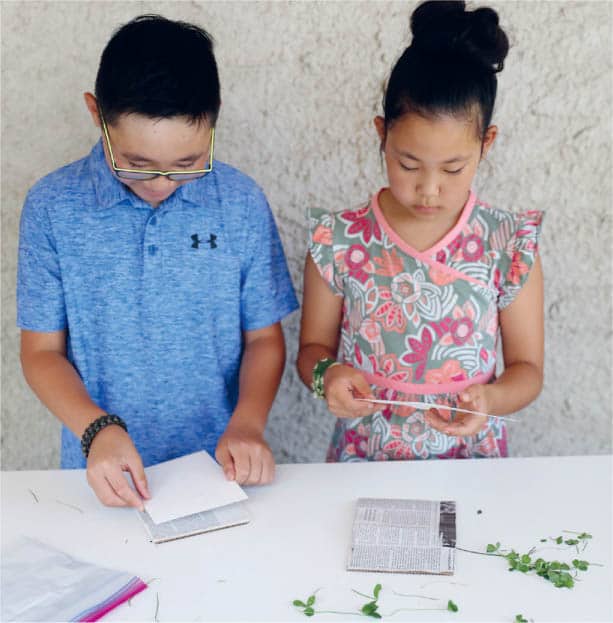

Ynés Mexía had a taste for adventure, braving earthquakes and poisonous berries to track down undiscovered plant species. You can get a taste of Mexía’s passion for botany by gathering leaves and blossoms in your neighborhood or favorite park. This lab teaches you how to press and label plants to create an impressive collection of your own. Before you go plant collecting, learn to identify harmful plants such as poison ivy, poison oak, and stinging nettles so you don’t end up with an uncomfortable rash. 1 Go on a plant-collecting expedition in your neighborhood or in a park. Fig. 1. Fig. 1. Go for a walk to look for plants. Bring a bag and some scissors or pruning shears. 2 When you find an interesting plant or tree, cut a branch, twig, or the entire plant, and put it in the bag to take with you. 3 If you have a camera, photograph the plant or tree you collected leaves from. Include extra photos, such as tree bark and stems, to aid in identification. Fig. 2. Fig. 2. Collect and photograph what you find. 4 Continue collecting plants and leaves until you have a nice collection. 5 When you return indoors, lay the plants out. Use a book, website, or app to identify what you’ve found. It is often helpful to look up plants commonly found in the general area where you collected them. The photographs should help, and leaf size, shape, and border are all features which will aid you in identifying what you’ve found. Fig. 3. Fig. 3. Lay the plants out. 6 To press the plants, cut a sheet of heavy paper sized to each plant. Fig. 4. Fig. 4. Cut paper slightly longer than each plant. 7 Cut a piece of newspaper to the same size and lay it on the heavy paper. Fig. 5. Fig. 5. Cut a piece of newspaper to lay over the heavy paper. 8 Place the plant leaves, stems, buds, and blossoms on the newspaper. 9 Lay another piece of newspaper on top of the plant and then add a second piece of heavy paper. Fig. 6. Fig. 6. Sandwich the plants between newspaper and heavy paper. 10 Continue layering plants and paper until you have a small stack. If using a plant press, put it on either side of the stack and secure it. Otherwise, place the stack between two pieces of cardboard and add weight to the top to press the plants. Large, heavy books work well for pressing plants. 11 Wait several weeks before pulling the stack apart to see the dried plants. Carefully glue them to heavy paper and label them with their common and scientific names. Record the date and place where they were collected. Fig. 7. Fig. 7. Label the plants when they are dry. CREATIVE ENRICHMENT Do some research to learn which insects inhabit the plants you collected. Try your hand at illustrating the plants and insects. (See Lab 1.) THE BIOLOGY BEHIND THE FUN Preserved plant specimens, such as those collected by Ynés Mexía, provide scientists with important information about plant diversity and distribution. Plants which have been dried correctly can last for hundreds of years. A collection of plant specimens and the recorded data about each plant is called a herbarium. Plant “discovery” refers to the first time that a plant is recorded for science. Although we no longer have the plants, some of the first plant-collecting expeditions on record were undertaken by the Chinese and the Egyptians. In Victorian England, plant-hunting was a popular hobby and collectors would travel around the world to collect live plants for their gardens. Today, scientists are also digitizing old plant collections and studying them to see how plant populations have changed through the years. Institutions, such as the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in the United States, now use DNA barcodes taken from living plants to identify species and store information.PLANT COLLECTION/IDENTIFICATION

MATERIALS

SAFETY TIPS AND HINTS

PROTOCOL