8

THE PRINCIPLE OF ETHICAL FINANCE

INVESTING AND LENDING FOR PEOPLE AND PLACE

Banks and pension funds invest for local wealth in Preston, England

![]()

The power of a few to manage the economic life of the nation must be diffused among the many or be transferred to the public and its democratically responsible government.

—FRANKLIN ROOSEVELT

“A fter so many years, I find myself in the mainstream now. It’s odd,” said Matthew Brown, in his distinctive British accent. “I’ve always found being in the minority more fascinating.”

Those days on the margin are receding rapidly for Matthew, a city council member since 2002 in Preston, England, who in 2018 was elected leader of the council and now travels the country to talk about all that he’s stirred up there. Matthew until recently worked a part- time government clerical job in addition to his Council work, spending evenings studying books on left- wing economics. As one reporter wrote, Matthew is a guy often seen with shoelaces untied, someone who grew up feeling “a sense of not being good enough,” as he put it. These days Matthew is featured in places like The Economist and The Times of London and serves as an adviser to the national Labour Party—which is itself experiencing an unexpected, swelling popularity. Labour might well form the next UK government. Some 60 cities and counties around the UK have reached out to Matthew—“too many to count,” he said—and at least 10 cities are actively replicating some of the work he helped lead in his own city: a multifaceted approach to building community wealth that has come to be known as the “Preston Model.”1

The turning point for Preston was 2011. That was when a large corporation pulled out of the massive Tithebarn shopping mall project, spelling the death knell for what had been the Council’s decade-long revitalization strategy. This high-poverty city was bereft: no money, no faith in a failing system, no plan. As the Council searched for ideas, Matthew heard about Ted, through Gordon Benson at the Centre for Local Economic Strategies (CLES). Out of the blue, Ted got a call out from this place he’d never heard of, Preston, asking him to come over. “It was amazing what they were doing in Cleveland,” Matthew said, speaking of the employee- owned Evergreen cooperatives supported by anchor institutions. “I was shocked that people in America were looking at that model, because I thought they would see it as too socialist. We decided to adapt it for a UK setting.”2

Although inspired by Cleveland, Preston ended up going far beyond Cleveland. Abandoning the idea of an absentee corporation as savior, Preston began cultivating locally owned firms. It started with Council support for creation of the Preston Cooperative Development Network, in partnership with the University of Central Lancashire. In 2012, Preston declared itself a living wage employer. The city also became an energy supplier by partnering with the municipal supplier Fairerpower Red Rose, saving consumers more than £2 million. The county pension fund—whose committee included the late Preston council leader Peter Rankin—allocated £150 million to local investment, including Preston projects like student housing and refurbishment of the once- grand Park Hotel.3

Most powerfully, Matthew worked with CLES on anchor institution spending, work which CLES had done previously in Manchester. CLES and the Preston Council identified £1 billion in anchor spending in 2012–2013, only 5 percent of which was spent locally. The Council sat down with six leading anchors—including the public housing authority, the University of Central Lancashire, and the local police authority—and persuaded them to buy more from Preston- based enterprises, such as farmers, printers, and construction firms. By 2016–2017, that 5 percent had grown to 18 percent in Preston, an increase of £75 million. Across the county of Lancashire, where Preston is located, anchor spending went from 39 to 79 percent, an increase of £200 million. This shift supported 4,500 jobs.4

The results have been remarkable. From 2016 to 2017, jobs in Preston paying less than a living wage dropped from 23 percent to 19 percent. Unemployment fell from 6.5 percent in 2014 to 3.1 percent. A 2018 study by PricewaterhouseCoopers and the London-based think tank Demos named Preston the most improved city in the UK and a better place to live than London. As Matthew said, the city had become more resilient by putting “more democracy and ownership in the Preston economy.”5

The trailblazer for much of this was Matthew. “For a long time, he will tell you that he was pretty much a lone voice,” Aditya Chakrabortty, senior economic commentator for The Guardian, told filmmaker Laura Flanders. “This isn’t a model out of a textbook,” he added. “It’s experiments. It’s things dreamt up in front of a laptop in the small hours of the morning with people thinking, what if I tried this idea.”6

ENERGIZING THE ELECTORATE

Matthew and his once-marginal ideas in Preston are now at the epicenter of a sea change in the political dialogue in Britain. Matthew was tapped by Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn to serve on a new Community Wealth Building unit in the party. The Economist dubbed Preston “Jeremy Corbyn’s Model Town.”7

In a manifesto for the 2017 general election, Labour laid out a transformative agenda for broadening ownership and remaking the economy “for the many, not the few,” Labour’s new slogan. Although “Britain is a long- established democracy,” the manifesto said, “the distribution of ownership of the country’s economy means that decisions about our economy are often made by a narrow elite.” The agenda included plans for protecting small business, growing worker- owned businesses, banning fracking, investing in renewable energy, and funneling support to local economies. In 2018, Labour announced a proposal to require all companies employing more than 250 to create worker ownership funds, giving workers a financial stake in their companies.8

Labour’s plans also call for public ownership of the railways, energy, water, and the Royal Mail. As economic advisor John McDonnell emphasized, these new publicly owned companies would be more democratic than old- style nationalized industries that were often “too bureaucratic and too removed from the reality” of workers. Support for public ownership in the UK is overwhelmingly positive, with 83 percent favoring publicly owned water, 77 percent publicly run energy, and 60 percent publicly owned railways.9

Although Labour didn’t win in 2017, it picked up an unexpected 40 percent of the vote, marginally behind the governing Conservative Party at 42 percent, despite what The Guardian termed a “thunderously hostile media.” As one Labour member of Parliament put it, “A lot of people were saying they were frightened of the future and wanted an alternative.”10

Labour’s national agenda, combined with Matthew’s local work, paints a picture of an emerging alternative system—capable of energizing a sizable electorate. There are lessons here about the surprising possibility of building real political power around a democratic economy agenda.

Beyond politics, another large-scale system dynamic at work in Preston and the UK is the power of finance. If climate change urges us toward a new sensibility—the ethical notion we have a responsibility to others, those alive today and in the future—finance in the extractive economy isn’t there yet. Implicitly, it’s built on the notion that finance dwells somehow in a realm apart, its rational workings removed from societal and ecological impacts, which need be considered only to the extent that capital is affected.

The democratic economy counterpoint is uncomplicated. It’s the principle of ethical finance: banking and finance exist to serve people and planet, with profit the result and not the primary aim. We can see this principle emerging in Preston, which is a kind of microcosm for the extractive economy’s long history, in which capital began as servant and ended up master—and is beginning, in small ways, to return to its true purpose.

A FATE BOUND UP WITH FINANCE

Preston in many ways was the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution—a cotton town where Richard Arkwright first created the spinning frame. As merchants in this rising new economy shipped materials, they obtained insurance from places like Edward Lloyd’s Coffeehouse, which would become Lloyd’s of London. Textiles and manufacturing helped make Preston a thriving mill town. But over the most recent half- century, capital and industry began to abandon Preston, as they did Cleveland.

The 2008 crash starkly demonstrated how intertwined Preston’s fortunes had become with the big London banks. Deregulation in the 1980s resulted in the UK having one of the most centralized banking systems in the developed world, with five large shareholder- owned banks controlling an astonishing 90 percent of the market. As these banks swallowed up local banks and once–mutually owned building societies, bank lending to the real economy—like locally owned businesses in Preston—shriveled. Today that amounts to less than 10 percent of total lending. The rest shifted to such areas as insurance and pension funds, consumer finance, and commercial real estate—and to such speculative areas as securitization, where loans are sliced and diced and sold.11

The 2008 implosion of those toxic financial products stopped building cranes dead across Britain. That spelled the end to the Tithebarn project in Preston’s city center. Although big banks were bailed out, Preston and other communities suffered through close to a decade of austerity due to shrinking aid from Westminster. By 2010, this town of 140,000 was near the bottom of the UK in terms of employment and well-being, with one in three children living in poverty. The birthplace of the Industrial Revolution had a new label, “the suicide capital of England.”12

As Preston began to take back its fate from the impersonal global forces of the extractive economy, one Council strategy was to rebuild local banking. “In my ward, the last branch of a major bank is shutting down,” Matthew said. This is typical of towns across Britain, where 762 bank branches were closed in 2017 alone.13 The Council supported CLEVR, a credit union owned by and run on behalf of its members, as well as a local community-oriented financial institution, Moneyline. That entity—which is national yet rooted in the communities it serves—operates as an alternative to predatory payday lenders, offering flexible, affordable short-term loans, with no additional fees for late or missed payments. These institutions aim to serve their clients, not to extract maximum profits from them.

The Preston City Council is also studying two new banking models being built in the UK, Hampshire Community Bank and the Community Savings Banking Association. The Council hired an expert to study both and to make a recommendation to Lancashire leaders in 2019. “Then anchors like the university can decide if they want to invest,” Matthew said. Hampshire Community Bank is modeled on Germany’s local public savings and cooperative banks (Sparkasse and Volksbank). Sparkasse—by law chartered to support their communities—control just 30 percent of bank assets yet do 70 percent of lending to small- and medium-sized enterprises.14

The UK’s Community Savings Banking Association, established in 2015 under the leadership of James Moore, aims to establish a network of 18 regional cooperative banks, each with a mission of local service. The banks will be controlled by customers, one member, one vote. The larger network will provide back office functions and regulatory support—essentially, a “bank in a box.”15

One of the first of these regional banks is Avon Mutual. Jules Peck, its founding director—also a research fellow with The Democracy Collaborative—explained the new local banking movement this way: “These new regionally focused, mission- led community banks are set to disrupt the banking sector and put sustainable development, people and planet, back at the heart of the UK investment sector.”16

BUILDING LOCALLY, SUPPORTING NATIONALLY

Preston has acted largely on its own while under siege, facing both austerity from the national government and the flight of capital from banks. The city will ultimately need national policy support. This is a key lesson for building a democratic economy: ventures can and often do begin at the local level. But to get to scale, government policies, particularly national ones, will be needed.

Labour has floated a variety of plans for creating a financial system beneficial to the real economy—including a proposed UK Investment Bank, modeled on other successful development banks like KfW in Germany. With assets of more than €500 billion, KfW played a countercyclical role in Germany during the financial crisis, increasing business lending 40 percent between 2007 and 2011, even as UK banks pulled back lending. KfW has special programs for small- and medium-sized businesses. It functions alongside the nation’s extensive network of regional and savings banks to create a diverse, locally rooted, healthy banking ecosystem.17

The US has something similar in the Bank of North Dakota, owned by the state. It supports a network of locally owned banks and credit unions, and as a result, North Dakota has close to six times as many local financial institutions per capita as the US overall. Because of this banking system, North Dakota made its way through the 2008 recession unscathed—inspiring a rising movement to consider publicly owned banks in places such as New York City, Los Angeles, San Francisco, St. Louis, New Mexico, and New Jersey.18

CENTRALIZED EXTRACTION VERSUS A NETWORK OF LOCAL FLOWS

At work are two ways of thinking about why finance exists. In the extractive economy, the aim is maximum financial income for an elite, which means wealth is often siphoned from communities by the absentee City of London or Wall Street.

Democratic economy finance design is closer to the vision of author and activist Jane Jacobs, who wrote about feeding widespread flourishing through dispersed local flows. Jacobs led the successful movement in New York City that saved Greenwich Village from the wrecking ball of master builder Robert Moses. In his modernist mindset, Moses envisioned a 10-lane superhighway soaring above the city, the construction of which would have leveled dense city blocks that had thrived since the Dutch settled Manhattan centuries earlier. Jacobs and her ragtag band of localists improbably stopped that highway. She wrote of expressway construction: “This is not the rebuilding of cities. This is the sacking of cities.”19

In a later book, The Nature of Economies, Jacobs observed that economic vitality depends upon enabling flows of energy throughout a system. Moses’s vision—like that of the big banks—can be likened to a single concrete channel feeding an absentee community, while Jacob’s vision is of a river fed by numberless tiny streams, enriching an entire landscape as it meanders through. One approach may be more efficient—for the narrow purposes of a particular group. The other is more resilient for the system overall.20

FINANCIALIZATION AND COLLAPSE

The extractive approach has been operating, full bore, in recent decades, leading to the phenomenon scholars call financialization. Author Kevin Phillips describes it as a process of financial services taking over “the dominant economic, cultural, and political role in a national economy.” Financial deregulation under Reagan and Thatcher in the 1980s encouraged the finance, insurance, and real estate sectors—collectively, the FIRE sector—to interweave so tightly as to be deemed a single sector. As this sector devised new ways to increase its income and assets, the economy’s center of gravity shifted. Less of GDP went to manufacturing, more to finance. Less to regular people, more to the financial elite.21

In the postwar years, manufacturing—making things in the real economy—was close to 30 percent of US GDP, while financial services was 11 percent. By 2000, this had flipped. FIRE sector revenues reached 20 percent of GDP; manufacturing slipped below 15 percent. As Phillips put it, the economy shifted from manufacturing stuff to manufacturing debt.22

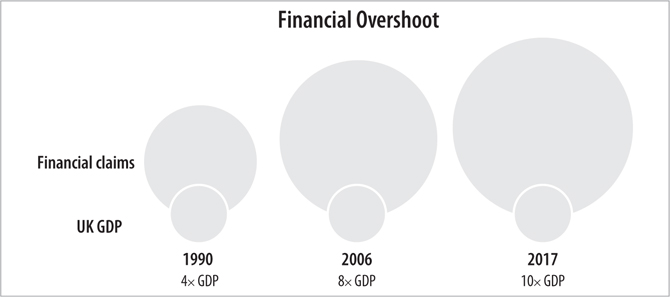

We can visualize the danger of this if we picture the financial economy as a sphere dwelling above the real economy, tapping its energy—like a debt load sitting on your shoulders. The financial economy is essentially a collection of assets, like stocks, bonds, loans, and mortgages. These are all claims against the real economy. Every dollar one person owes as debt is held by someone else as an asset. Equity in companies works similarly; stockholders have a claim against company earnings.

Consider the UK, for example. In 1990, private sector financial assets (securities, loans, equities, pensions, insurance) were about four times GDP. The debt load was four times as big as the economy that supported it. But as financial extraction revved into high gear—more mortgages, more profits, more debt—the sum of financial claims ballooned. By the year 2006, this debt load had swollen to double its previous size in relation to GDP. Now the sphere of debt was eight times as big as the economy supporting it. Similar trends were happening in the US and elsewhere.23

This set the stage for the 2008 collapse. As mortgage lenders ran out of reasonable mortgages to write, they began to issue reckless ones that could never be paid back. The house of financial wealth was becoming too large. Yet because the system’s essence was insatiability, its logic could not comprehend the idea of too much financial wealth. Thus more claims—and more absurd claims—were manufactured until the debt load exceeded the load- bearing capacity of the real economy. The system entered a phase of financial overshoot, much like ecological overshoot.24

Governments responded by propping up the overbuilt system. That prepared the way for the cycle to repeat itself. As UK economic analyst Howard Reed observed, the financial sector in the UK shrank after the financial crash, but began expanding again in 2015. “More shockingly,” he wrote, “total UK private sector debt—including securities, loans, equities and insurance—rose from 430 percent of GDP in 1990 to 960 percent in 2017.”25 (See Figure 2. Definition of debt is securities, loans, equities, pensions, and insurance in the private sector—corporate and household, not government debt.)

FIGURE 2. The UK private sector debt load in relation to GDP doubled between 1990 and 2006, from four to eight times GDP, helping trigger the 2008 crisis. Yet today, the UK private sector debt load is larger, 10 times GDP.26

In short: Private sector financial claims in the UK are now nearly ten times GDP. No living system grows rapidly forever. Cancer attempts to do so, and in the process, kills its host.

The notion that finance is sucking too much out of the real economy is not an abstraction in places like Preston and elsewhere in the north of England. Wealth is systematically extracted from them and then controlled by the City of London, the British analog of Wall Street. On a per capita basis, the government also invests half as much in the North as it does in London, according to John McDonnell of the Labour Party.27

The problem with extractive economy finance is not only that it is unfair to working people, drives perpetual growth, and contributes to ecological crises, it’s that the system is programmed for its own implosion. It is a snake devouring its tail.

The IMF has warned of “storm clouds” gathering for a new financial crisis; billionaire investor Paul Tudor Jones has highlighted a “global debt bubble”; and fund manager Jim Rogers has predicted a financial crash that will be the biggest in his 76 years. The financial community has taken to talk of the “everything bubble”—the massive runup in the value of stocks, real estate, and other assets—with the New York Times asking, “what might prove the pinprick”?28

PATHWAYS FOR ETHICAL FINANCE

For those interested in building the democratic economy, the question is: Will government again prop up the extractive system? Or can we seize the opportunity to advance democratic economy finance? There is “another way forward, grounded in long-term public ownership of financial institutions,” writes our colleague Thomas Hanna. In the last crisis, the US government de facto nationalized some of the big financial players, only to later simply return them to private ownership. In the UK, the government still holds control of the big bank RBS, which taxpayers bailed out in 2008 to the tune of £45 billion. The New Economics Foundation has proposed bringing RBS wholly into public ownership, breaking it into a network of 130 local banks. In the US, Hanna has similarly proposed that in the next crisis, policymakers consider converting failed banks to permanent public ownership.29 It would be wise for progressives to have such a plan in place. What seems outlandish one day can become eminently practical in a crisis.

There are many other pathways for ethical finance to advance—including through responsible investment processes such as fossil fuel divestment, support for green bonds, and impact investing. The largest generational transfer of wealth in history—$50 trillion—is coming, with the passing of the Baby Boom generation.30 Many inheritors will be women, who are known to be disposed toward ethical investing, as are many millennial investors.31

Imagine if we invested not only for people and planet, but to advance democratic economy institutions that create broad- based asset ownership—ensuring great wealth never again accumulates in the hands of a tiny elite. One such approach is investing in employee ownership. Back in Cleveland, the new Fund for Employee Ownership was recently launched by the leaders of the Evergreen Cooperatives, Brett Jones and John McMicken, working with our colleague Jessica Rose as strategic adviser. It’s housed at the Evergreen Cooperative Development Fund, which helped finance the Evergreen Cooperative Laundry—the place Chris Brown landed after three years in prison, and where he advanced to plant supervisor.

The fund will purchase privately held companies and convert them to employee ownership, creating good work, anchoring wealth in community, and generating value for investors. After proof of concept in Northeast Ohio, the fund plans to go national. The aim is to demonstrate how mission- driven capital can be leveraged to help business owners sell their firms, offering them “an experience that’s as frictionless as any other exit option they have available to them,” Jessica said.32

At The Democracy Collaborative, we believe capital is the missing partner needed to take employee ownership to scale. Investment banker Dick May of American Working Capital suggests that $100 billion in federal loan guarantees would create a magnet for private capital that would support the creation of 13 million new employee owners in a decade, doubling today’s number.33 That’s just one example of the vital role capital can play in building a democratic economy.

![]()

As more cities began to call on Matthew Brown, Ted found funding to enable him to become a senior fellow at The Democracy Collaborative, enabling him to devote full time to spreading the Preston Model. “I’m finally free,” Matthew told us. For Matthew, free means working 50 to 60 hours a week and traveling nonstop.

“Eight to nine London Councils are interested,” he said. “The Scottish government shows interest. The Welsh assembly is looking at it. Also the Metro Mayor of Liverpool,” he added. “You’re talking a hell of a lot. We were even invited to speak with the Number 10 policy unit in Downing St. There’s something in that.”34

In the early days, “when I was coming up with all these ideas, people liked them, but they said, can this work?” he recalled. Now, “people are excited.” For 40 years, there’s been no alternative, “just managed decline.” But now, “With the pension fund, anchor procurement, the living wage, worker co- ops getting started, the credit union, the bank,” Matthew said, “we’re really building a democratic economy.”