CHAPTER 19

Leadership: Starting with the Core Leadership Team

The third component of the organizational play book is leadership. The only thing you can do all by yourself is fail. Successful mergers and acquisitions require an interdependent team with its members all paddling in the same direction.

Select “new” management team members based on the alignment of their motivations, strengths, and personal preferences with your vision for the new combined entity.

There are only three job interview questions. In the vast majority of cases each of the candidates for your leadership team has the strengths required to do the job. And while the main reason people fail in new leadership roles is poor fit, that's relatively difficult to assess up front. This leaves motivation as the most important criteria for selection. Be ready to probe all three interview questions, but lead with motivation.1

Let's unpack that.

There are only three true job interview questions:

- Will you love the job?

- Can you do the job?

- Can we tolerate working with you?

Every question you've ever been asked or asked others in an interview is about understanding motivation, strengths, or fit.

Lead with motivation. As Simon Sinek put it in his TED Talk, “People don't buy what you do. They buy why you do it.”2 It was true when he said it, and it's even truer as Millennials have become the largest cohort in the workforce and the largest cohort of leaders. And Millennials tend to be purpose-driven.

This means you should no longer choose people for what they can do. Choose for why they do it. You do care about how people's strengths can help solve problems. You also care about being able to tolerate the people working with you. But jobs are increasingly going to those with the best alignment of motivation.

The key is happiness. Happiness is good. Actually, it's three goods: doing good for others, doing things you're good at, and doing good for yourself. Everyone operates with some balance of the three—with different biases and balances. The answer to the motivation question, “Why would you want this job?” reveals that bias:3

- If they talk about the impact and effect they could have on others, their bias is most likely to do good for others.

- If they talk about how the job could allow them to leverage their strengths, their bias is most likely to do things they are good at.

- If they talk about how the job could fit with their own goals or progresses them toward those goals, their bias is most likely to do things that are good for them.

Knowing that bias informs where you should go with the interview. Essentially,

- If their bias fits with what you're looking for, go on to probe strengths and fit.

- If you're not sure, dig deeper into their motivations by going through different levels of why or impact questions until you are sure.

- If their bias does not fit with what you're looking for, end the interview. How you do this can range from going through the motions of completing the interview to letting them ask you questions, to walking out.

Order matters. Everything you do and say affects what follows. If you start your interview by probing strengths and then ask someone why they would want the job, they may try to mold their answer to fit what they infer is important to you from your questions about strengths. They may think your question is another way for you to get at strengths. Similarly, if you start your interview by probing fit and then ask about motivation, they may try to mold their question to convince you of their fit. So, start with the motivation question—without any biases.

While the world generally needs more other-focused leaders, this may not be true for your particular situation. The strongest leaders and strongest organizations over time will be, indeed, other-focused. They think outside-in, starting with the good they can do for others. They are the leaders and organizations people will want to work for over time, will want to learn from, and will want to help.

Still, you may need to focus more on strengths, building required strengths to ensure your near-term survival so you can be other-focused later. You may need to be a little more self-focused so you can attract and leverage people who think “good for me” first, so you can build some momentum.

Following are three sample answers to why someone wants the chief financial officer (CFO) job at an organization working to improve doctor–patient interactions:

- “I see how I can contribute to improving your financial operations and help you through the coming exit to private equity investors.” (Good at it)

- “This one's a money-maker that can fund my retirement plan.” (Good for me)

- “Some of my family members' health care was compromised by poor interactions with their doctors. I want to be part of helping you fix that.” (Good for others)

The choice is yours. In any case, figuring out what drives the person you're interviewing is your most important task in an interview for any role—and especially for your new leadership team. Make it your first task.

Strengths

People used to work their way up from apprentices to journeymen to master craftsmen. This involved 7-year apprenticeships as indentured servants living, eating, and working alongside master craftsmen and their families. While some of that is way out of date, some of it still makes sense.4

Gallup suggests strengths are made up of talent, knowledge, and skills. Adding experience and craft takes that to a different, even more valuable level. These build on each other.

- Innate talent: born with or not

- Learned knowledge: from books, classes, training

- Practiced skills: from intentional, deliberate repetition

- Hard-won experience: digested from real-world mistakes

- Apprenticed craft: artistic care and sensibilities absorbed from masters over time

Innate Talent

Gallup defines talent as “the natural capacity for excellence.” But in Bounce, Matthew Syed suggests talent is a myth and that it all comes down to practice.5 They could both be right in that it may be possible to overcome some lack of talent with deliberate practice. But having innate talent has to make it easier.

Learned Knowledge

Almost every society on the planet agrees that education is a basic human right. Investing in learning always pays off. The more people learn about a subject, the better.

Practiced Skills

As the old saying goes, “What's the best way to get to Carnegie Hall? Practice. Practice. Practice.” But, as many have pointed it out, aimless, random practice gets you nowhere. Skills are built with intentional, deliberate repetition of important things so they become second nature.

Hard-Won Experience

To benefit from our mistakes, we have to be in a position to make them, understand them, and digest them so we don't repeat them. Practice works for things people do on their own. For things people do together or with an impact on others, people need experience.

Consider an orchestra preparing for a concert. Each member learns their part of the music. Each member practices to sharpen their own skills. Both are necessary, but not sufficient. They need to rehearse together to build a shared experience and make their mistakes then and not in the performance.

This is part of why U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower invaded North Africa before Europe during World War II—so his soldiers could get experience in battles they could afford to lose before engaging in the ones they could not afford to lose.

Apprenticed Craft

Craft-level artistic care and sensibilities are not innate talents. They can't be learned. You can't practice them. And while experience is important, it's not enough. Real mastery of a craft is handed down from master to apprentice over an extended period of time.

Theater legend Oscar Hammerstein handed down his craft to Stephen Sondheim. Sondheim saw Hammerstein as a surrogate father, worked as a $25-a-week gofer at age 17 on Hammerstein's show Allegro, and devoted himself to Hammerstein's tutorials on rhyme, characterization and storytelling, and demanding homework.

College football coaching legend Nick Saban was an apprentice to NFL coaching legend Bill Belichick of the New England Patriots for 4 years before going to the University of Alabama. Their attention to detail, systems, and processes are still so similar that players moving from Alabama to the Patriots hardly feel like they are switching coaches.

Great sushi chefs start their apprenticeships with years of rice making.

No one goes straight from medical school to being a surgeon. They spend years as residents (apprentices).

Eisenhower learned his craft as a general by serving on the general staff of several other great generals (as an apprentice) before he ever commanded armies in battle.

Implications for You

Know what you want from the people on your leadership team. Talent, knowledge, and skills always matter. Experience takes you to the next level—only if it is hard-won. Mastering a craft requires a whole different level of commitment.

General Atlantic's Talent Playbook

In their book Talent, General Atlantic managing director Anish Batlaw and coauthor Ram Charan note that talent is “the single most significant variable in differentiating outstanding performance from just good success,” with performance defined as equity value, not just EBITDA.6

When George spoke with them, Charan said, “Talent is the value creator and competitive advantage.” To that end, Batlaw and General Atlantic created a talent playbook integrally linked with the investment side of their business. That playbook has three main parts: diagnosis, strategy, and actions. As Charan pointed out, the value is in the subheads.

Talent Diagnostic

General Atlantic's talent team works with its investment teams to create scorecards of the practices, processes, people, and decision-making required to enable and scale talent to achieve the investment theses. They use those scorecards to assess individuals' and the teams' potential to quadruple revenues in 3–5 years.

Charan says that's what's different versus 99.9 percent of companies—the focus on 3–5 years down the road. The key, he says, is “experience and learning agility” and understanding: (1) talent; (2) organizational structure; (3) operating rhythm; (4) culture (how people treat each other); (5) key performance indicators (KPIs); and (6) incentives and compensation and how all these are synchronized with speed and momentum.

Talent Strategy

General Atlantic's talent strategies flow from the “most important imperative of the business whether it's action on new market penetration, doing multiple M&As [mergers and acquisitions], fixing pricing, new products” or something else.

For example, Batlaw explained that the keys to realizing General Atlantic's investment thesis for Gen Z–focused fashion resale marketplace Depop were rapid expansion in the United States and superior digital marketing. They had just moved the head of the U.S. operation to London, leaving a gap in the United States. Then General Atlantic determined the core talent strategy was to fill that gap while building out digital marketing strengths in the United States at the same time.

Charan noted that “the greatest mistake is (a lack of) intellectual honesty and rigor on the most important critical priority. It can't be negotiated, downplayed, or compromised.” The business strategy must start with customers. General Atlantic's value creation journey begins with choices around which customers to serve and how to serve them in a differentiated way focused on either design and innovation, production, delivery, or service.

For example, General Atlantic invested in Hemnet, Sweden's dominant online site for real estate listings. They saw expansion opportunities that “would take an aggressive new plan and a new corporate culture oriented toward product innovation, customer focus, and results.” That customer-led focus determines the required people, culture, and infrastructure—the talent strategy.

Talent Actions

General Atlantic has learned to move quickly on people. “We found that when we made a mistake with a chief executive officer (CEO) change, the average internal rate of return (IRR) for those deals dropped by about 82 percent compared with when we got the CEO change right the first time. In addition, when a change was successfully executed within the first year of the deal, the average IRR ended up being six times greater than if the change was made after the first year.”

They design the right organization for the future, leverage their talent bank of almost 5,000 pre-vetted executives, and fill positions within 6 months of a deal closing (sometimes even before).

Batlaw highlighted some things about their search process:

- Their search and assessment criteria flow from the same scorecards they develop with the investment teams. They look hard at:

Candidates' track records

Strategic thinking and acumen (analytic capabilities, command of data)

Learning agility (hunger for information and knowledge, willingness to seek out support)

Drive for results, commercial acumen, and operations management

Team leadership

Interpersonal influence

- They use reference checks not to ask people how they feel about the candidates but to validate the stories candidates told them about how they achieved success.

- They tie incentives to future value creation, deemphasizing cash in favor of long-term incentives.

Things Change

Disciplined and consistent follow through and operations management are essential. But things change, investment theses adjust, and companies outgrow some of their leaders.

As General Atlantic's CEO Bill Ford put it, growth CEOs often “instinctively know they have people on the team who have been successful in the first chapter but who aren't equipped to support the company through its next phase of growth.”

Team Synergies over Individual Strengths

Employees perform at different levels, when on different teams, in different situations, with different people. That probably makes sense to everyone. Why then do so few leaders spend so little time looking for synergies on their teams and so much time looking at individual performance? Because realizing synergies is hard work, and there has been no framework for doing so.7

The Skills Plus Minus Framework

Phil and Allan Maymin and Eugene Shen began their Skills Plus Minus presentation at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Sloan Sports Analytics Conference by asking who basketball's better point guard was from 2006 to 2008. Was it Deron Williams, who then played for the Utah Jazz, or was it Chris Paul, who played for the New Orleans Hornets at the time?

The data is inconclusive with regard to the original question, but it does show that either player would have been even more valuable had he been on the other team. Had the Jazz and the Hornets done a one-for-one, straight-up trade, each team would have been better off. Their stars might or might not have performed better, but the entire teams would have performed better.

The presenters looked at individual skills and events, including offensive and defensive ball handling, rebounding, and scoring. Then they looked at those skills and events in the company of other players to determine the positive and negative impact of players on each other. If two players each steal the ball from their opponents two times per game on their own but together steal the ball five times per game when they are on the court together, that's a positive synergy.

Applying the Skills Plus Minus Framework to Your Team

Of course, it's important to understand the strengths of the individuals on your team. That always will be important. But that's just the first step. The only way to optimize synergies on a team is to leverage differentiated individual strengths in complementary ways.

In a hypothetical example, one manager is particularly strong at managing details, one at operations, and one is particularly strong at encouraging creativity. Unfortunately, the guy with the operating strength is managing the group that needs to be creative; the more creative guy is managing a group that needed to pay attention to details; and the detail-oriented manager is trying to manage a complex operation. Moving each to the right role frees everyone up to perform better.

It's not just about the individuals. It's about the individuals in the context of the tasks that need to get done and the other individuals involved.

Let us propose a couple of steps flowing from the BRAVE leadership model:

- Understand the context in terms of where you choose to play and what matters.

- Determine the attitude, relationships, and behaviors required to deliver what matters.

- Evaluate each individual's attitudinal, relationship, and behavioral strengths.

- Structure the work in a way that allows individuals to complement each other's strengths.

- Monitor, evaluate, and adjust along the way.

The pivot point is leveraging complementary strengths across attitudinal, relationship, and behavioral elements. The specifics of those are going to be different in each different situation. That gets us back to the initial point. But now you've got a framework. So there's no excuse not to pay as much attention to potential team synergies as you do to individuals' strengths.

Fit

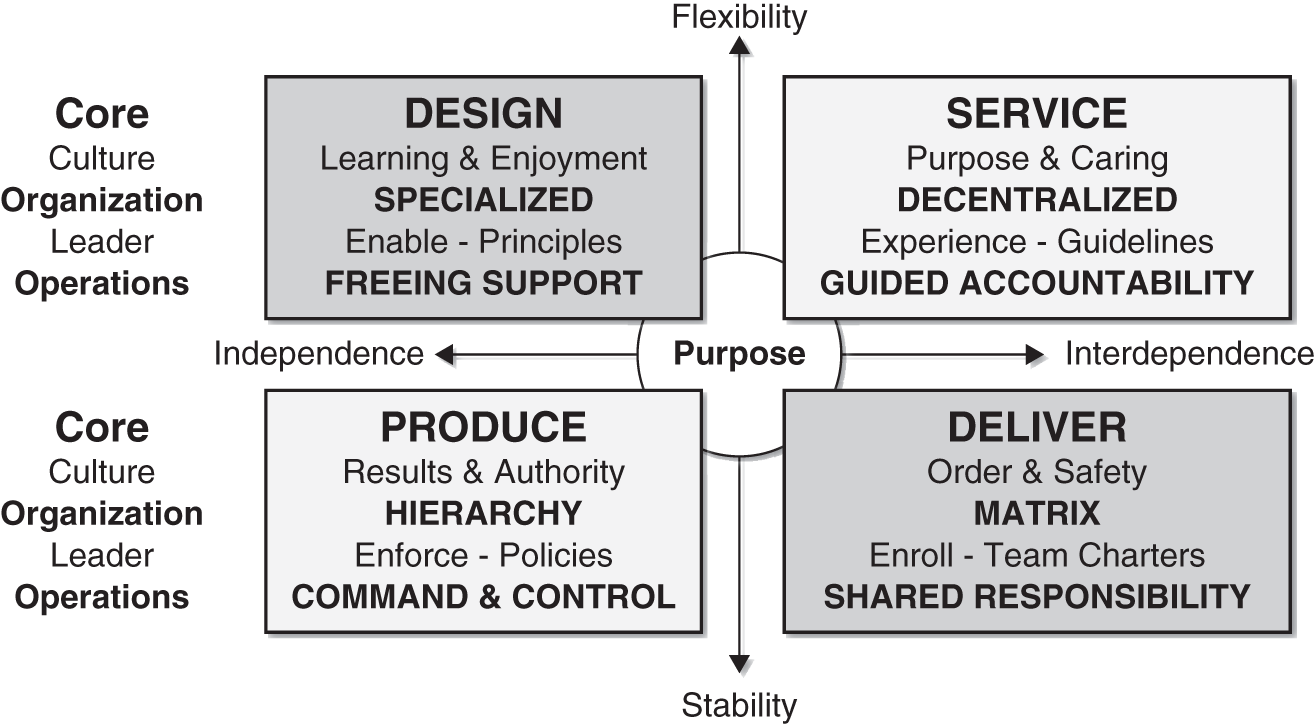

Fit goes to the alignment of their personal preferences across behaviors, relationships, attitudes, values, and environment with the culture you are creating. This goes right back to your core focus. That focus and your cultural choices are inextricably linked.

One coal mining company's leadership team was split on whether they should be production or service focused. Those arguing for production focused said their essential business was moving dirt to uncover coal and they needed to be the low-cost producer. Those arguing for a service focus said that solving their utility company customers' problems was the only way to differentiate.

They wondered if they could do both.

They could not.

The required cultures were diametrically opposite. Service requires a customer-back decentralized flexibility to create more value for customers and earn a higher price. Production requires stability and a command-and-control attention to details to achieve the lowest total cost.

The critical question for this coal company was whether their best-serviced, most loyal customers could be lured away by a competitor offering them a 5 cent/ton lower price. The answer was yes, reinforcing the need for a production focus.

At a high level, as depicted in Figure 19.1:

- Design-focused organizations are generally marked by cultures of independence, flexibility, learning, and enjoyment led with freeing support.

- Produce-focused organizations are generally marked by cultures of stability, independence, results, and authority led with command and control.

- Deliver-focused organizations are generally marked by cultures of interdependence, stability, order, and safety, led with shared responsibility

- Service-focused organizations are generally marked by cultures of flexibility, interdependence, purpose, and caring, led with guided accountability.

FIGURE 19.1 Core Focus

Choose leadership team members who agree with this core focus choice and can fit with this choice. In the next breath (and next chapter) you'll co-create plans.

One CEO told his people that they were going to make 90 percent of the operating decisions and that, as CEO, he was going to have to support them. He said 6 percent of decisions they'd make together and 4 percent were his to make, and he expected them to support his decisions.

The core focus decision was made as part of the investment case and confirmed during due diligence. It falls into the 4 percent of decisions that others are going to need to support. The high-level plans fall into the 6 percent of decisions that the new leadership team are going to make together. The distinction is important when it comes to inspiring, enabling, and empowering others.

For decisions that have to go through you, you're the choke point at the bottom of the funnel, controlling the flow. Conversely, when you provide clear direction, resources, bounded authority, and accountability, enabling others to make decisions, you turn the funnel into a megaphone, amplifying your influence and impact. It's one of the fundamental differences between early-stage entrepreneurs and successful leaders of larger, more complex enterprises.8

Decision-Enabling

Coca-Cola's Neville Isdell was a decision-enabler. He led by giving people:

- Direction as to the desired objectives and results so everyone understood his intent.

- Resources—the human, financial, technical, and operational resources—needed to succeed.

- Bounded authority to make tactical decisions within the strategic boundaries and guidelines all had agreed to.

- Accountability by way of standards of performance, time expectations, and positive and negative consequences of success and failure for those held to account.

It's counterintuitive, but clear direction, boundaries, and guidelines free people up to act. Knowing what you can't do lets you spend more time thinking about what you can do. Coca-Cola's people knew they couldn't mess with the core pillars of Coca-Cola. No one tried to change the secret formula. (Except once with New Coke. But that's a different story.) Global package changes were big deals. But people had tremendous flexibility with local advertising, promotions, and execution, enabling the tactical capacity to adjust quickly and decisively.

Isdell deliberately spent more time enabling others' decisions than in making decisions himself.

Here's the point. Taking the core focus discussion off the table for your new leadership team allows them to spend their time thinking through and managing how to make it work.

Executive Onboarding

The most important lesson in Bob Iger's book The Ride of a Lifetime is that “a little respect goes a long way, and the absence of it is often very costly.” Respect yourself, colleagues, and brand.9

Respect Yourself

A big part of self-respect is self-confidence—enough to own up to your own mistakes with confident humility. Quoting Iger:

- “You'll be more respected and trusted by the people around you if you honestly own up to your mistakes. It's impossible not to make them; but it is possible to acknowledge them, learn from them, and set an example that it's okay to get things wrong sometimes.”10

- “You can't pretend to be someone you're not or to know something you don't.”

- “You can't let humility prevent you from leading.”

For example, Iger's boss at ABC sports, Roone Arledge, treated him “differently, with higher regard, it seemed, from that moment on” after he owned up to a big mistake.

Respect Colleagues

Iger learned to respect others' different strengths. Of content creators, Iger wrote, “Everything is subjective; there is often no right or wrong. The passion it takes to create something is powerful, and most creators are understandably sensitive when their vision or execution is questioned.”11

In line with that, when he was Disney's CEO, Michael Eisner taught Iger “how to see” in a way he had not been able to do before. “Michael walked through the world with a set designer's eye, and while he wasn't a natural mentor, it felt like a kind of apprenticeship to follow him around and watch him work.”

And Iger's bosses at Cap Cities, Tom Murphy and Dan Burke, “hired people who were smart and decent and hardworking, they put those people in positions of big responsibility, and they gave them the support and autonomy needed to do the job.”

Respect Brand

Iger learned to get at the heart of the brand.

For example, ABC Sports told big stories in depth. “No detail was too small for Roone. Perfection was the result of getting all the little things right.”

Don't confuse this with doing everything. Iger learned from branding and political consultant Scott Miller that if you have too many priorities (as in more than three), “they're no longer priorities.” He went on to say, “Not only do you undermine their significance by having too many, but nobody is going to remember them all.”12

You live your values in what you walk by as well as in what you do. When Roseanne Barr started tweeting some “thoughtless, occasionally offensive” things, Iger took her out to lunch and persuaded her to agree to stay off Twitter.

When she did not, tweeting something even more offensive, Iger fired her. It was an easy decision for him, guided by his principle that “there's nothing more important than the quality and integrity of your people and your product”—your brand.

Respectful Executive Onboarding

Respect for brand, self, colleagues—and their needs—were critical components of Iger's being able to attract and onboard the key people from Pixar, Marvel, and Lucas Films to add technology, talent, and characters propelling Disney into the future:

- Pixar's Steve Jobs, John Lasseter, and Ed Catmull needed Disney to respect the essence of Pixar.

- Ike Perlmutter needed Disney to value the Marvel team and give them the chance to thrive in their new company.

- George Lucas needed to trust that his legacy, his “baby,” Star Wars, would be in good hands at Disney.

Iger earned their trust over time. Each of them had known Iger or known of him and how he treated others for years before they even started thinking about possible mergers.

When Lucas was considering selling to Disney, Jobs told him that Iger had stood by his word. Iger had said, “It doesn't make any sense for us to buy you for what you are and then turn you into something else.” He then honored the two-page “social compact” of culturally significant issues and items that Disney had promised to preserve in Pixar—and then Marvel and then Star Wars.

It's not an either–or choice. When onboarding executives individually or as part of a merger or acquisition, respect yourself, them, all your colleagues, and the brands.

The most up-to-date, full, editable versions of all tools are downloadable at primegenesis.com/tools.

Notes

- 1 Bradt, George, 2017, “Why You Should Lead with Motivation in Answering the Only Three True Job Interview Questions,” Forbes (April 30).

- 2 Sinek, Simon, 2010, “How Great Leaders Inspire Action,” TED Talk (May 4).

- 3 Bradt, George, 2019, “Why Your First Interview Question Should Be ‘Why Would You Want This Job?'” Forbes (January 2).

- 4 Bradt, George, 2022, “Why the Highest Level of Strength—Craft-Level Master—Requires Apprenticeship,” Forbes (January 4).

- 5 Syed, Mathew. 2011, Bounce: The Myth of Talent and the Power of Practice (London: Fourth Estate).

- 6 Bradt, George, 2022, “Ram Charan and Anish Batlaw on General Atlantic's Private Equity Talent Playbook,” Forbes (January 25).

- 7 Bradt, George, 2012, “A Framework for Turning Individuals' Strengths into Team Synergies,” Forbes (September 18).

- 8 Bradt, George, 2021, “Why and How You Should Switch to Decision-Enabling from Decision-Making,” Forbes (April 13).

- 9 Bradt, George, 2022, “Executive Onboarding Lessons from Disney's Bob Iger,” Forbes (February 25).

- 10 Iger, Robert, 2019, The Ride of a Lifetime: Lessons Learned from 15 Years as CEO of the Walt Disney Company (New York: Random House).

- 11 Ibid.

- 12 Ibid.