Chapter 3. As We Lead

The road to success is dotted with many tempting parking places.

Enabling Organizational Velocity

Some of us have the challenge of leading people and initiatives in addition to being champions of ideas. This expanded role offers a lot more opportunities in the area of collaborative strategy creation. For most of us, leading is a privilege that comes in addition to our regular, everyday workloads, work that each of us must perform flawlessly because resources—talent, budgets, headcount, and schedules—aren’t as abundant as we might want or need. Leading collaborative strategy is not as easy as it looks.

Perhaps a story of a newly minted general manager will highlight the point.

Not long ago, a Rubicon colleague asked me to take a meeting with Lucas, who had recently received a prestigious new role at a global media company. The meeting was framed up as an opportunity to explore creative new ways to drive “exponential growth” in what pundits might very well consider a mature business unit.

We talked over lunch at a bustling Greek restaurant. Lucas was sharp, creative, and ambitious. He came across as a confident executive and a strong leader. Nearly two hours disappeared as we spoke about corporate and divisional strategic issues, focused intensely on the questions related to growth. We talked about Lucas’s passion for his products and services, and the initiatives he wanted to start and the goals he had. He shared a plethora of detailed facts, keen observations, and expansive ideas.

In particular, his division’s current annual revenue was $338M, and he believed that his division was well positioned to outpace the overall company’s expected low double-digit growth rate. Based on his fresh perspective and new understanding of the dynamics driving his business, Lucas had concluded that it was possible to drive it toward a much higher goal. Indeed, he was looking at how to achieve triple-digit growth!

Emphatically, Lucas told me that he wanted his team to step up and figure out how to tackle this huge potential opportunity. He recognized, however, that there was at least one obstacle. Lucas was self-aware enough to know that he was enmeshed in too much of his team’s individual detail work. He observed himself offering more specific direction than was appropriate given the talent of the people reporting to him. Plus, he had the vague sense his people were somehow holding back.

Between the talking, eating, and drinking, I began a mini-version of my Fact Gathering interview (which we’ll cover in Chapter 4) to learn more about Lucas’s business and to explore various ways I might be able to help him. We explored dozens of possible approaches to accelerate growth, and looked at creating new product and service offerings to crack open and win new markets.

Whenever I asked Lucas a question that challenged his basic point of view, I saw his eyes light up. “Wow. That’s a good idea,” he would say. Or, “Oh, I think that would work....”

Lucas responded more passionately to a particular category of questions than others: he had energy around optimizing channels of distribution, creating new offers, performing customer requirement research, and conducting quantitative analysis. Questions that had specific and factual answers prompted Lucas to sit forward in his chair.

In contrast, some questions didn’t move Lucas a bit. For example, he wasn’t terribly interested when I asked him questions like: “So what do you do to generate ideas from your people?” or “Does your team believe this growth is possible, too?” or “Where, specifically, are your people limited in their decision making and initiative?” His responses were flat. At best, he would mutter something cordial or polite like, “Hmm. That’s probably worth looking into.”

Over the next couple of days, I found myself mulling over the conversation, trying to put my finger on the source of Lucas’s mixed responses to my questions. Only when I had consciously set the topic aside could I see the odd reality of the situation: Lucas was standing directly in his own way.

Lucas was obviously interested in finding creative, innovative ways to win. There was absolutely no question he wanted to be a growth leader, to help his team take real ownership of market opportunities. However, it had become abundantly clear to me that Lucas’s natural strength as a gifted problem solver was somehow more compelling to him than his less-developed collaborative skills. This dynamic was holding Lucas back, as it does for many otherwise effective executives, and biasing him toward a definitive, smartest-guy-in-the-room approach to strategizing and winning.

Tip

The very thing that helps leaders get to their role of leadership biases them toward a “smartest-guy-in-the-room” approach to strategizing.

Even though Lucas was very much aware he needed his team to step up, he had not recognized his role in getting them to co-own problems and co-create solutions. Meanwhile, the familiar territory of largely solo problem solving had Lucas’s sharp intellect literally champing at the bit. I’d seen this before.

If my previous experience was any guide, Lucas’s personal challenge was due to conflicting imperatives. On the one hand, he believed himself to be the champion who would be able to find the answers to the tough questions that would ultimately lead to the success he envisioned. On the other hand, he was sensitive to the fact that his team, not he alone, had the knowledge, talent, and capacity to step up and ultimately deliver those breakthrough results. Is it possible to do both? Put another way, can someone in Lucas’s position simultaneously find the strategy “answer” and get people to step up and engage? This question is the heart of the challenge for most executives.

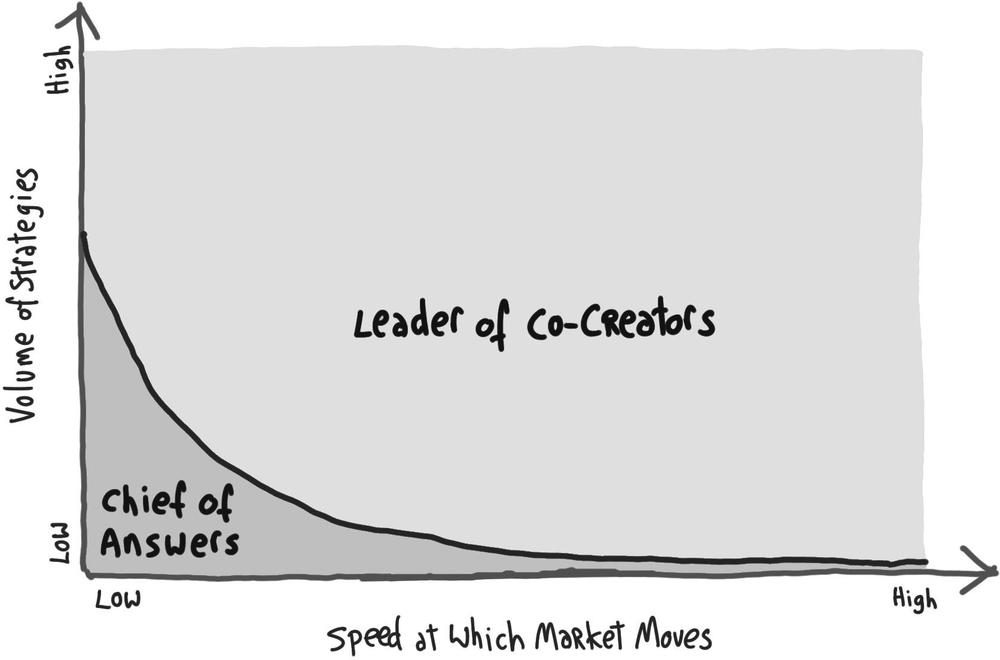

Talented people are chosen for leadership positions because they possess some keen talent, insights, vision, and/or extraordinary problem-solving skills. And often they find it easier to exercise these skills than to teach them or coach others to use their talents more. To add to the challenge, attempts to promote collaboration are often unrewarded in our current work culture. So it often happens that our Achilles heel as leaders is attempting to come up with the answers and solve the tough problems by ourselves (Figure 3-1).

Perhaps you see a bit of yourself in Lucas’s story? From your personal experience, have you come to believe that you can solve problems faster on your own than you would through any group effort? This is a dangerous type of trap for us leaders, because it lures us into believing that we alone can answer the most vexing questions and solve the toughest problems. And so, rather than collaborating with the people, engaging knowledge, and tapping into the talent within the organization, we go it alone.

If you see yourself in this story, you’ve got company. This is more the norm than the exception, and the more complicated the business issue, the more likely people are to “go it alone.” The upshot is that leaders often figure out “the answer” solo or in small groups, then set direction and tell their teams to “execute.” Voilà, the Air Sandwich is manifest, and organizational velocity is not achieved.

Here is what I later said to Lucas—something I wish I could say to all GMs, VPs, directors, and managers in similar situations:

The answer to today’s specific question is only that—part of the solution to today’s problem. Next week’s problem will require a different solution. And next month’s question will need yet another answer. Crowning yourself the Chief of Answers puts you in a difficult position, one with very little advantage. It sets your team up to be the Tribe of Doing Things. And, at the end of the day, you end up feeding the very counterproductive cycle you need to alter.

Our past successes bias us. They reinforce our tacit worldview that, as the smartest person in the room, we can avoid the messy dynamics of group problem solving. All we need are access to credible data, great research, excellent analysis, and clever insights. Our past successes reinforce our misguided belief that we can come up with the best strategic idea faster and far more efficiently on our own rather than slowing down to collaborate with our people.

The Chief of Answers model fails the organization on multiple levels. Here are a few:

Scalability. Having everything go through one leader (or a small set of leaders) limits growth. The number of different kinds of business challenges grows as the market speeds up. The Chief of Answers cannot know the multitude of issues as well as the people who are closer to the problem. The speed of changing issues, the trend of that rate of change, and the speed at which the organization must react is crucial to competitiveness going forward.

Ownership. When people understand the reasons things are broken, why decisions are made the way they are, and so on, they ultimately own the thinking. This means they can own the outcome. Without this understanding, only a few people feel ownership for the success of the strategy; the rest are collecting paychecks.

Retention. Our incoming workforce of millennials expects to play a big role in setting direction. This group of people with new ideas can choose which organization to work with.

Motivation. Sitting outside the room doesn’t motivate people. They want a seat at the table. When a Chief of Answers leads, the best people go to organizations where they can make a more meaningful impact.

The Chief of Answers model rests mostly on individual smarts. But we all know that setting direction requires more than an accumulation of facts, processes, formulas, and individual insights. It is about going beyond data, insights, and models. It’s about applying many different perspectives and challenging the status quo, making shifts inside the organization and jointly steering it toward a new, compelling future. It’s about getting many people to understand, believe, co-create, and co-own the outcome of a strategy, thus turning a direction into reality.

The End of the Era of the Chief of Answers

When a leader crowns himself the Chief of Answers, making him the key person responsible for driving all strategy, he creates a bottleneck in the organization. By not involving other people in the strategy process, things get bogged down (see Figure 3-2), and it’s a struggle to do strategy creation effectively. Under these conditions, his people will always be dependent on him, and he will be the limiter of what could otherwise develop into a fast, responsive, adaptive organization. What we want instead is a leader of co-creators.

Recognizing and accepting that the Chief of Answers (CoA) model is obsolete is not always easy. Many of us began our careers during a time when that model was still well regarded, and we’ve invested a lot in building a set of skills and perhaps a reputation as Chief of Answers (though we don’t call it that; we use the terms “whiz kid” or “go-getter”). And some industries move slowly enough that Chiefs of Answers can still manage to keep up. But in the complex and dynamic industries, the CoA model is toast. RIP. And it’s critical for this reality to be internalized by everyone who wants to lead a vibrant and powerful team trying to win in those markets. There is a lot of commonality between the failures of the CoA model and why strategies have been failing.

Responsiveness is key to future competitiveness. One person or a very small number of people cannot keep up with a) the number of issues, and b) the rate at which they move. And of course the trend is toward more and faster. Because customers who depend on us are also experiencing these trends, a key differentiator among companies is responsiveness. Responding quickly and well depends on how quickly and accurately information and decisions flow through the organization. Responsiveness also depends on how a company listens, discerns, learns, and organizes itself to respond quickly to what customers will pay for (knowing full well that what they say they want today might change tomorrow).

Many of today’s fast-paced industries were just about manageable 10 or 15 years ago, but since then all kinds of complications have been layered on. Outsourcing, localization, increased automation, open licensing, shared APIs, Software as a Service (SaaS) models, and middleware dynamics can all be big factors in decisions, whereas they were only peripheral elements before.

Our shift toward the “information economy” and “knowledge workers” means that we have few turn-the-crank jobs left. We have leveraged machinery, software, and overseas labor farms to handle routine and predictable work wherever possible so that we can compete. Predictably, our teams are now full of highly educated, experienced, specialized smart people doing work that requires care and judgment.

On the one hand, we need these people to care about the work that they do, and on the other hand, we would love to take advantage of what they see, anticipate, and imagine. We as their leaders want them to get what we’re envisioning, and tell us how it’s either wonderful or broken. We want to know how they could make it better. We even want each of them to know what others are thinking, to generate concepts and solutions that would not have been conceivable otherwise.

This model of a fully engaged “wisdom workforce” is incompatible with the CoA model. If you don’t actively engage people throughout the organization, you will struggle to get them to agree on what’s most important and what success will look like. If you’ve hired well, these people won’t be happy sitting on the bench; they want game time!

Yet, according to research, we don’t treat them like participants and co-creators of the business outcome.

Only 5% of the workforce understands its company’s strategy.[8] Only 1 person in 20 is prepared to answer, clearly and realistically, what her company should be doing and how her individual efforts contribute to supporting it. (“You don’t know the strategy? But I sent out the slide deck!”) See Figure 3-3.

Tip

Only 5% of the workforce understands its company’s strategy.

Can people really be effective without knowing the strategy? Not likely.

There’s a real potential to use the fuller organization to consider and make decisions quickly, based on information that comes from the depths and edges of the company, from customers, partners, and suppliers. This builds a team of professionals.

The Goal Is Repeated Wins

Existing or aspiring leaders who may see a bit of themselves in Lucas’s story may be reacting to this collaborative workforce vision in two ways. First, it may seem as though I’m suggesting that you are no longer a key strategist. Second, you may wonder if you need a new skill set to be a leader of champions.

To answer the first question, no, you’re not abdicating the role of key strategist. You’re simply gaining new leverage. Let’s put to rest the notion that the goal is to get to one big win, because the ultimate goal isn’t to win once but rather to win over and over again. As leaders, the way to do this is by increasing the quality of ideas and speeding up decision making by helping our teams collaborate and co-create, and by distributing the ability to solve the toughest problems throughout the organization. Together, this creates the conditions for our companies to outshine the competition by out-thinking them, out-creating them, and out-innovating them...repeatedly.

And to answer the second question, yes, you’ll need some new approaches. You will want to shift the organizational processes that influence how people input ideas, develop options, and make decisions. And we need to influence the protocols for how people vet ideas and communicate risks and dependencies with one another, so that decisions align to form a unified direction. The protocols must allow for productive deliberations and checkpoints while avoiding red tape, bureaucracy, and politics. By keeping the focus on repeated wins, you are avoiding the parking places on the road to success.

Transitioning to the Un-Hero

With this in mind, the way you lead and set direction makes a big difference. How do you do this, you wonder? How do you help a group of people do more than just find the answers to their current problems? Is it really possible to help other people who are responsible for leading ideas to develop the ability to be more strategic on an ongoing basis and to think for the organization as a whole? In short, how do you get your team to fill the Air Sandwich?

Tip

The ultimate goal isn’t to win once, but rather to win over and over again.

The short answer is this: you make clear that it matters, invite your people to participate, ask them to help, and provide guidance. As we lead, we have countless opportunities to speed up strategy creation and execution by facilitating conversations across organizational silos, divisions, functions, and departments. So, your job as a leader now includes being a catalyst to connect people and help them combine forces, develop their ideas, and tap their collective knowledge, experience, and strengths. Rather than telling people what to do, you will find opportunities to guide them by sharing your unique point of view, by teasing out insights, concerns, requirements, needs, issues, and experiences, and by asking the question that is on everybody’s mind regarding how the needs of the business might be addressed. In some ways, your role is to be a new kind of corporate hero.

Look, it’s only natural that each of us aspires to be a bit of a hero. And, as a collaborative strategy leader, you will be a hero. But you’ll also be a kind of “un-hero.” Un-heros are essential. Even Batman needed the un-hero Alfred, because the hero character would be too far-fetched without an amazing helper. You can be both Robin and Alfred to your team’s Batman. When you contribute toward fostering the new culture of collective strategy creation, you’re a hero! When you set the context and allow people to act as co-creators of ideas, you’re a hero! When work is challenging, people are valued, and turnover is low, you’re a hero! When you lead actively in ways that bolster the successes in your organization and company at large, you’re a hero! Your team will be basking in the spotlight, which means you’ll spend more time as Bruce Wayne and less time in the cape and tights. (That’s OK; they get itchy if you wear them too long anyway.) You’ll have plenty to do as an “un-hero” because you will facilitate as much as you decide, catalyze as much as you act, and coach as much as you direct.

Your contribution to the big successes will be clear and critical, but the accolades will be shared because success will be distributed. Others will own, develop, and be responsible for various pieces of the success. In your new capacity, you will lead people through influence and ideas instead of just authority. They will ultimately create, own, and be responsible for executing against the direction that you initiated and they sharpened. You will be the director of a symphony, playing a piece of music co-written by you and the orchestra.

Your real power as a leader now comes less from having the right answer, perfect judgment, and insights about which direction to go, and more from your ability to create the kind of environment where your people can:

Learn about and understand situations fully (to solve real problems rather than just symptoms)

Engage with one another meaningfully so any issues or obstacles are identified early on

Strategize together to build upon one another’s ideas and design a new future

Lead aspects of the strategy you collectively develop

Hold the big picture in mind when making trade-offs and decisions are needed

Your ability to be effective depends heavily on how you go about doing what you do. Stylistic aspects of your leadership, which might be hard to identify at first, will have tremendous impact. This may pose a challenge if, for example, you’re the kind of leader who is highly action oriented. You might be tempted to tackle your role in a decisive yes/no and “get it done” manner. (Catalyzed conversations? Check! Helped people develop ideas? Check!) Resist! Leading idea co-creators, managing and inspiring people in a coordinated fashion, requires a more nuanced and, particularly at first, patient approach.

To be successful, you need to facilitate two things. You must enable and then encourage people to step into their new roles as co-creators of solutions. And you will need to help your entire organization to think more strategically. Your ability to do these two things forms the centerpiece of your new approach to leading.

The way you lead matters a lot, because you are the one nurturing an environment where people bring their creativity to bear. You are the one encouraging people to think about the problem with new options. You are the one encouraging them to own the solution so that execution goes faster in the market. You are creating the forum where people give you and your organization what they most love—their ideas and passion.

But people won’t give their ideas and passion if they think their leaders won’t treat them with care. So you’re going to have to be a trustworthy person who gains people’s confidence. You will treat people’s ideas with regard; you will be willing to engage creative tension so tough discussions can take place; you will be flexible in your own vision so your ideas can morph into the one that will actually work. Being a leader of co-creators is not for the weak-kneed and spineless. This type of leadership works only if the leader is ready to bring a certain amount of emotional maturity and intelligence. You may not have all the skills you need to do this kind of leadership today, but if you can be aware of and self-manage your learning without fear, none of these skills is out of your grasp (see Figure 3-4).

Engaging your team in a preview of the strategy while it’s being developed provides valuable exposure to the thinking around what matters to the organization. When the team knows what’s coming, they have an opportunity to think ahead, anticipate obstacles, and imagine possible solutions before the problems even arise. This think-anticipate-imagine process also helps your team to get comfortable with the idea of change. Their participation drives a legitimate sense of co-ownership in the ultimate decision. Understanding, readiness, and co-ownership together speed up conversations and improve the quality of the strategy as it is being implemented.

Remember that at most firms only 5% of the workforce understands the strategy. As you lead, strive to help ensure that the team, organization, and/or company achieves a 20/20 score rather than the abysmal 1 in 20.

That is how you begin to change the norms. You become more of an organizational leader—in other words, you are putting the success of your entire organization first, creating safety to co-create solutions, and making sure that the how of strategy gets created along with the what. You are creating a New How.

The Seven Responsibilities

Just as for individual champions of ideas, the way you do your job has a huge impact on your team’s readiness to collaborate. Your approach to leading influences how you establish (or reestablish) connections among your company’s people and their ideas. The patterns of thinking and acting that we demonstrate unlock how our people create and execute new strategies for the business. As you lead, you can transform how people work, interact, and talk with one another so that the root causes of the Air Sandwich start to resolve themselves naturally.

In your role as a collaborative leader, you can change the way we work and unlock the power of people and their ideas by taking on seven responsibilities. Together, these responsibilities are about establishing a new mindset for yourself and fostering a similar mindset in each team member. The seven responsibilities are:

Manage Cadence

Generate Ideas

Nurture Safe Culture

Develop Connections

Satisfice

Engage Issues

Trace Topography

To simplify the job of maintaining your awareness of these responsibilities, I’ve arranged their labels so that they spell out the word “mindset.” Let’s explore each of these responsibilities and why they are part of the way we lead collaborative strategy.

1. Manage Cadence

Managing cadence is about setting the pace. From your vantage point, you’ll show your team how they are progressing, so they can sense incremental accomplishment and thus maintain a sense of forward motion. You will always keep people informed to let them know where they are and what other mountains lie ahead. You will use whatever means are appropriate and comfortable, regardless of whether you rely on “one-on-ones,” email, voicemail updates, or standing meetings.

Pay attention to the frequency, volume, and duration of your communication. Pace matters. Be cautious that you don’t drive your people so hard that they fatigue and become less effective. (And this applies to you, the leader, also! Go to the gym, garden, whatever helps you stay balanced, and do it regularly to mentally reboot.) Operating for extended periods at just a few percentage points over their capacity can leave people feeling overwhelmed and apprehensive about participating. Push hard, take a break and assess the pace, and then push hard again.

If you observe that your direction and communication leave people energized and looking forward to meeting each new challenge, then you may have found a good pace. Still, remember that a good pace for the team might be too fast for some individual members of that team, depending on what other responsibilities they have. Stay attuned to pacing at the individual level as well as at the team level.

Also pay special attention to what people are saying about the process, and don’t shy away from asking them how they feel.

If and when the collaborative strategy process gets chaotic or confusing, remember to reorient people, manage expectations, and set context whenever the need arises.

You will manage various phases of the methodology covered in detail in Part II. Keep that context in mind when checking on people’s response to pace. If you hear your people saying things such as “I don’t know which way is up,” consider:

Investing the time to reorient them in whatever way seems appropriate. It might make sense to reassure them that the process is right on track.

Reminding them which phase of the process they are currently in.

Informing them of what’s likely to happen next.

Pointing out how much time is left in the current phase.

Giving them a break from the activity to chill and to reboot their gray matter.

Generally, acting as an “Official Process Guide” is easy if you maintain a clear view of the big picture and where you all are in the thick of it. Remember to communicate it early and often so others know it, too.

You can give your people a sense of security by making it clear that it’s your responsibility to guide them forward. This will help individual team members be open to stepping outside of their comfort zones and taking risks that might pay off further down the road.

Keep people in the loop and let them know what else is going on. Feel free to send quick one-liner emails, or use microblogging tools to let the team know that things are on track. It’s a great idea to send a quick note when someone on the team has gained a useful insight; for example, “Joelle just did 30 phone calls with customers and learned that the key reason why advertisers are using our competitor is xyz.”

Celebrate milestones. It’s simple yet powerful to send a message or “tweet” when you accomplish something, even something small. You can even celebrate team learning. Collaborative strategy creation can, at times, be a challenging back-and-forth process, so help your team coalesce and stay aligned by helping them create meaning around what they are doing. If your team has just finished deciding something they deem important to the company, celebrate it. Celebrate the fact that your team has declared, “This really matters to us.” Help your team manage perspective by seeing that they belong to something larger than themselves, and that as a group they are contributing to something greater. What you punctuate with your actions and language indicates what is important to you and will be noticed.

When you invest in managing team perspective, you help people stay in motion. This keeps the overall momentum up, and when people sense they are in motion, they are far more likely to continue putting in the effort to make progress.

2. Generate Ideas

Sparking ideas is about illuminating insights, empowering people to see what they already know in a new light. When you perform this assignment, you’ll often find yourself generating ideas as you create new connections, as well as reinvigorating existing connections. You will use these interactions to create fresh opportunities that allow ideas to bubble to the surface, expand, and even pop.

New ideas and solutions to present-day problems rarely fall out of a cloudless blue sky. What typically precipitates a new idea is a shift in thinking prompted by the tension between competing ideas, or the pressure of an unexpected challenge in a tight timeframe. Sometimes new technologies can spark that shift in thinking. Another rich source of opportunities comes from talking to others about specific improvements, especially if the improvements are driven by outside market forces. Conducting brainstorming sessions can also be a good source of concept sparks. Such sessions have the added value of helping people to explore the natural tensions that create friction between opposing ideas.

Sometimes ideas come back from groups and they are counterintuitive to a leader’s experience or wishes. When that happens, you get to take them on then and there, rather than have that perspective hidden within the hearts and minds of people. Idea generation with the spark of debate leads to shaping each other’s ideas, but it also can be about explaining why something really won’t work. It doesn’t mean that a leader has to succumb to the mass democratic nature of the people generating ideas. Collaboration is not meant to be a democracy, but rather a meritocracy or a benevolent dictatorship in which the larger good of the company is achieved.

Ask your people to find ways to clear their minds and inspire new thinking, such as listening to an insightful industry speaker, hunting down interesting blogs, or watching a TED talk.[9] In each case, the topic may be only peripherally related to work. You might share a radical new concept and push the group to “prove you wrong,” just to stir things up and give them practice at convincing you of what they believe. It also lets them see that you don’t expect everthing you say to be treated as gospel.

Frequently challenge assumptions. Question the way things are. How did the status quo become the status quo? Probe and challenge in situations where your team can learn that doing so is accepted and valid. Make sure your team is fully supported as they come up with the best ideas possible to solve your particular strategy problem.

People will share their ideas most effectively in the right environment. And so another one of your responsibilities is nurturing a safe environment that invites new ideas.

3. Nurture Safe Culture

Leading collaborative strategy requires nurturing a culture in which people feel safe, so that you lower the sense of risk people feel as they begin to work together to invent new solutions. A simple reality of collaboration is that people can’t create together if they don’t trust each other.

Some people find that team-building activities let them get acquainted, begin establishing a sense of trust, and have conflict-free conversations before the pressure of schedules, budgets, and conflicting interests enter the picture. Once your people feel safe enough to risk expressing their precious ideas, you must encourage everyone to bring their best selves and creative ideas to the table. Your job is not to control this, but to facilitate it (Figure 3-5).

To create the space for people to express their opinions without fear of ridicule or condemnation, you must temper your own criticism and that of others. Insist that criticism is given constructively so that it pushes the conversation forward and advances learning.

In a larger sense, your job involves welcoming and accepting contradictory voices. Although there is an appropriate time to critique and discard weak ideas (as we will highlight in the process framework), most organizations have a number of team members that are adept at “stone throwing.” We need to get all the ideas out in order to discover the good ones, and that is not as easily done if people are afraid of getting stones thrown at their ideas. Ask that people express their opinions and ideas so that they build on the ideas of others rather than chip away at them. A great example of this happens in improv theater where participants learn to say “yes, and” instead of “no, but.” This technique keeps the conversation moving forward. Both Google and Whole Foods offer their people classes in improv to teach them how to apply these kinds of techniques in business.[10]

The story of Hans Grande in the sidebar "Profile of a Collaborative Leader" on page 87 provides a memorable example from my own experience of someone who was extraordinarily successful in building a culture where people felt comfortable collaborating.

As we reflect on how Hans approached his assignment, we can see that he did more than simply create safety. He also established connections. It’s a part of our job as leaders to build the bridges that bring people together and create a group or ensemble to address particular challenges or problems. Developing connections across boundaries—across corporate silos, divisions, functions, departments, and teams—is at the heart of building a truly productive and collaborative environment.

4. Develop Connections

Developing connections is about bridging divides, large and small. When working on this assignment to assemble the right group of people to tackle an issue, you will be linking departments, divisions, and individuals across the organization in new and sometimes unexpected ways. You will use your understanding of how different parts of your organization operate, and you’ll encourage conversations across the invisible boundaries that might have kept people from working together in the past.

As you compose any team, think about individual personality types and styles. Whether you rely on systems such as Myers-Briggs, colors, or the Enneagram, or you use your own “spidey-sense” intuition, keep in mind that certain styles can be quite compatible or incompatible, and that “compatible” may not mean “similar.”

Do what you can to encourage that every connection is a kind of creative partnership. However, if a specific connection doesn’t click, try building a connection with a different person, one where there’s better chemistry between people.

As you build each connection, carefully think through each choice you are making and how it will impact the team, because it will determine who’s at the table and who needs to play what role. By figuring out who specifically needs to engage and by catalyzing the right connections, you will help different parts of the organization come together and work on the problem at hand.

Developing connections is particularly important because addressing the toughest challenges in business requires getting the right people to work together in alignment with a shared vision of success.

And connecting people across organizational boundaries lets you leverage the company’s strengths, wherever they happen to be found.

As you initiate connections, provide context of business issues to discuss. Kindle each connection with the spark of a new idea to test the chemistry. New ideas provide the fuel and the energy to develop creative new solutions to ever-changing problems. New ideas provide the power for collaborative strategy.

One thing that everyone will want to know is when you have arrived at a destination. Please note that there are many destinations along the way to the end of a project. As simple as this might sound, you’d be amazed to discover how difficult most people find the process of recognizing the finish line. When there is no checkered flag, how do you know when you’re done? As a leader, you can clarify where the finish line is by influencing how and when decisions are made. In particular, you can orient your team to recognize situations where seeking the absolute best option is not justified. Quite often, it is more than acceptable to achieve a milestone or result that is “good enough,” meaning it meets or exceeds the needs of the situation. This is the process of satisficing.

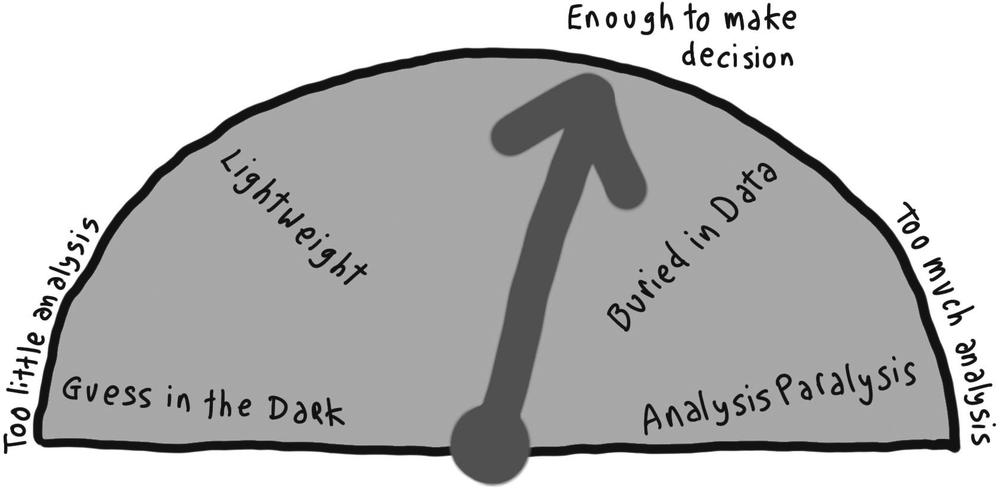

5. Satisfice

The job of figuring out when done is done (or when you need to keep trying) is a judgment call. When I discovered the concept of satisficing many years ago (in Scientific American, of all places), I found the word that describes the perfect stopping point.[11] Satisficing is a decision-making strategy that uses criteria for adequacy rather than perfection. It’s a concept that helps us know when we’re done. Satisficing is about defining when enough is enough and it’s time to move on. It is a pragmatic alternative to maximizing, minimizing, or optimizing. When you engage this technique, you choose to stop one thing and move on to another while managing the time and resource constraints. You help your team make the best decisions for the situation at hand, knowing that you might need to make more decisions later.

Satisficing is the opposite of trying to achieve the “perfect” solution. As Voltaire said, “The perfect is the enemy of the good.” When you’re balancing a dozen competing demands, there is no clear notion of “perfect,” so seeking it does not add value. Other times, investing in some element makes no difference to the larger outcome. Does your website need a custom feedback form? Or is an email address enough? Would travelers choose Southwest more often if it served almonds and cashews, or are they really driven by low fares and on-time arrivals? Satisficing is about helping your people recognize they’ve succeeded given the scope of what you were working on (Figure 3-6). Sometimes peanuts are a perfectly acceptable answer.

6. Engage Issues

When you engage the issues, you lead the simple act of getting people to talk. You pose questions such as: What will it take us to address this problem? Is this something we are willing to look at right now? Do we all agree on what the full problem is? Do we agree this is a priority for us given where we are on other things? Which factors are most critical to our success?

Engaging the issues is an act of bravery because you demonstrate the ability to deal with issues head-on. Engaging the issues does not mean having the answers, but it does mean being committed to learning. For example, where someone says X is the most important problem and another says the most critical issue is Y, the question to ask is: how can both be true? It is possible you will learn that X is most important to customers and Y is most important to finance (or operations, or channel partners). By engaging the issues, you create the opportunity to learn what the organization is willing to do in more detail.

Engaging the issues accomplishes two things that can dramatically shape culture. It allows you to:

Communicate to the people working around you that you value openness and risk taking.

Lead by example, showing your people they can acknowledge the truth and talk about it.

People at all levels actually want to be able to understand the issues, they want to be able to talk about what is really going on, and they want to do it without fear.

By engaging the issues, you lead this effort, giving others permission to speak to what they see, ask questions, and contribute freely. By choosing to engage the issues, you shed light into dark corners and take the discussions in your company to a higher level. You also diffuse pent-up concerns that something important is being ignored.

Tip

Most people don’t see how conflict can serve business. They think appeasing everyone creates peace, but that just waters down solutions. It is our ability to work through tension that resolves issues and creates new solutions.

In general, people tend to shy away from engaging the issues in an effort to protect themselves. They fear difficult conversations, and they want to avoid feeling uncomfortable, incompetent, unsuccessful, or blamed. They don’t want to be perceived as causing conflict. When a culture lacks a pattern of dealing cleanly and fairly with tension and conflicting viewpoints, those natural avoidance behaviors are understandable. Not healthy, but understandable.

However, engaging the issues does not mean blame, judgment, or conflict. It does mean having conversations about present and future risks, such as customers defecting, competition winning, or markets disappearing. We have these conversations because the benefits of engaging the issues will ultimately outweigh the consequences of staying silent.

Engaging the issues requires some consideration about how people might receive information. Avoid getting personal, and keep the discussion focused on the business impact. For example, don’t say, “What Kristine did is causing a lot of pain.” Instead, you might say, “This situation is impacting us a lot. What would it actually cost us to solve the problem?”

Often problems arise through reasonable actions, and it can sometimes help to acknowledge this: “It seems that in the rush to meet our last milestone, we took some shortcuts. That’s understandable, but as often happens, some of the shortcuts have caused a problem, and we need to deal with it. Do we have the capacity to solve this problem now? What would be the impact of waiting six months?” By showing the impact and asking questions with room for choice, you empower your colleagues to decide how best to move forward.

By engaging the issues and opening up a dialogue, you enable your company to begin talking about key decision points. It is not necessary to get commitment about solving a problem, only to get the conversation going, so that it can be solved at some point in time. In some situations, you may find that a group’s decision to postpone dealing with a particular problem can be the absolute right decision, if, for example, there is a larger issue that needs addressing first. If you find yourself unable to deal with conflict and you avoid it to the detriment of yourself or your business, figure out the underlying reason and resolve it by participating in the Hoffman Program referenced in Appendix B.

To make it easier to engage the issues, here are some helpful hints:

Take other people’s perspectives into account, and speak as though you are peers. Refer to Appendix B for resources on how to speak the truth with clarity and power.

How do you tell a powerful leader that you think he is missing something? The answer is to get inside his mind and see through his eyes. This can sound like: “It seems like we’re doing A, B, and C because we’re assuming X, Y, and Z are going to happen. But there’s a real chance that Y will not turn out quite the way we’re anticipating. We might be better off doing D, E, and F instead. Can we talk about that?” The more articulate and specific you can be, the more you can have a conversation about facts, and not about who is right or wrong.

Keep the conversation on topic. The curious thing about dealing with the issues is that people often want to go off into the weeds. Tangential topics can pop up, and people will get uncomfortable and want to change the subject. People often want to defend their actions, even when no one is targeting them. They may feel anxiety and implicit blame. You can defuse much of that anxiety by taking a brief moment to acknowledge that the current situation may very well have arisen from legitimate and reasonable efforts. Make the point that the discussion at hand is focused on moving forward, not looking backward.

Name your intent (and keep reinforcing it if you need to). It often helps people to accept your involvement when you tell them why you are involved and what your interests are. It’s also helpful to tie the topic to what the person, company, division, or team wants. When asked to research an issue, it’s useful to share with everyone involved that your purpose is not to find the flaw in what’s not working (and to blame), but to help the team find out what to do next and regain its success.

Be open about your own mistakes and culpability (if they exist). Be up front about your past contributions to the situation, if any, and focus the conversation on the present and the future. Show your humanity and lead by example. Don’t leave it to others to tell you that the emperor has no clothes.

Stay focused on simply engaging with the issues versus finding a specific outcome. When well-intentioned people engage on a topic, they will often uncover misunderstandings, and it may take some time to find a resolution. The less attached you are to a particular outcome, the more you can simply focus on getting people to start talking and making progress.

Engage a professional facilitator or someone from elsewhere in the firm (like Hans Grande) if you personally expect to be an active participant in the discussion. A facilitator will be able to help you by tracking and managing the rational, emotional, and intuitive parts of the discussion. This will leave you free to participate fully in the conversation.

Be open to learning. You will likely find out something you don’t yet know or don’t want to see. Without being open to whatever comes, you can’t work through the tension.

You set the tone by what you allow to happen and by what you reinforce or ignore. Whenever you are involved, engage the issues in a healthy way. I’ve had executives watch an aggressive power play happen right in front of them and say, “I’ll let you two work it out.” That rarely works; instead, it signals that it’s OK to do power plays within the organization. If you let power games go unchecked, you are setting up a catastrophic failure in your business. You may not want to choose sides, but you can strongly urge that the merits of the issue get addressed instead of allowing the issue to become political.

Keep power games and passive-aggressive behavior in check. If you let them go unchecked, you end up letting people work from positional power, which undermines the power of good ideas. It ends only when we say that it’s not OK to work from positional power. To get from us-versus-them to a collaborative culture, that stuff is no longer allowed (see Figure 3-7).

Our cultural norm going forward is about having each of us co-create our future, defining together what we want to build for our teams, divisions, or companies. So we need to start demanding that people focus on the problem and get on the same side of the table to do it.

Tell your people that any energy spent showing one another up is wasted energy that could have been spent on winning the market. (A tip: when I see a power play, I find just chuckling and saying, “What’s that about? Are you taking that approach because you don’t have a good cost-benefit argument for your position?” works wonders to get people to cut it out.) And if you tend to hush up issues as a way to avoid conflict, just know that you are missing out on opportunities to learn. Conflict is a signal that there may be an opportunity to improve on the status quo. Until some shift happens (like learning a new fact or point of view), change and growth never can.

When creating strategy, maintaining forward progress is essential to overall success; satisficing supports this. When you engage this responsibility, you establish what is ahead and make sure that people don’t get stuck in one place for too long. The next responsibility is about navigating the terrain.

7. Trace Topography

The collaborative strategy process is most effective when teams use the phases of the process described in Part II. But it’s not always easy to do. Nuisances and distractions unavoidably crop up. You must manage these things. When you perform this assignment, you’ll be holding the “topo map” of where you are, even when your team is mired in the details of the rugged terrain. You’ll remind your team of the larger goals and guide them away from paths that you know lead to a dead end.

In this role, you’ll answer questions. You’ll give directions. You’ll encourage your team to keep going even when they feel lost. When there is a decision to make, you will know what this decision looks like at the ground level and how it fits into the larger landscape of what you are trying to do. This, of course, means that you keep perspective and don’t get caught up in the act of doing.

One common nuisance is that some team members will tend to arrive at a new phase of a process unprepared for what they are about to do. This is normal when people have a lot on their plates. Still, it’s essential to ensure that participants do not accidentally sabotage the process with their lack of adequate preparation, and part of this responsibility is pushing the members to be prepared.

Conversely, other team members will be all fired up and itching for the next phase before the rest of the team has agreed to close the current one. This is also normal. Normal or not, collaborative strategy requires that people support constant progress. They must work together in a loosely coordinated fashion to ensure that the necessary work gets done at roughly the right time and is of adequate quality to support constant progress. Your job is to help them.

All the nuisances and challenges of keeping creative, motivated human beings focused and working together require sequencing. Sequencing what, you ask? Sequencing is an advanced, high-level skill related to managing the following:

Logical flow of conversations among people

Steps of work that follow one another

Hierarchical decision making

It is about managing the readiness of change.

The best way to manage orientation is to stay on top of events and activities as they unfold over time. You can achieve this simply by staying keenly aware of what’s happening as it’s happening.

By doing two things consistently, there is a simple way to accomplish this: establish an explicit purpose or intent for everything the team must do, and refrain from holding regular meetings out of habit, regardless of cultural norms or the convenience of setting up an automated, recurring calendar event. Yes, I’m giving you permission to have fewer meetings. That biweekly meeting in which you see eyes glazing over like Krispy Kremes? You’re allowed to cancel it.

Instead, convene people in ways to keep the team fresh. Move in small groups or in other flexible ways so you are not designing strategy “by committee.” Spend less time knowing the answers in advance; instead, clarify the agenda each time you meet with any department, team, group, or subgroup, and start each session with what you need to accomplish together and why it matters.

Maintaining strong momentum through the process requires that you proactively work to minimize the nuisances. As we lead, our deep understanding of collaborative strategy phasing gives us a leg up and helps emphasize when we need to:

Foreshadow what’s to come

Begin preparing the next phase

Celebrate meeting all of the objectives in the phase you’re working on

In short, you know and signal when team members can embark on the next phase.

It can go without saying (but I’ll say it anyway) that preparing for the next phase includes making sure the current phase of the collaborative strategy process is being done thoroughly enough, and that critical resources—especially time—are available in sufficient quantities to complete the next phase.

Here is a simple example of sequencing that recently took place with one of my long-term strategy clients:

The head of sales operations and her extended team were working hard to redefine part of their channel strategy, but they were facing a dilemma. On the one hand, they were under pressure to implement some near-term changes to reduce costs. On the other hand, they wanted time to think through longer-term product assortment issues, i.e., which products are sold by which channel.

The key was to figure out what issues needed to get resolved immediately while simultaneously leaving the door open wide enough to change the product assortment in case the product team later arrived at another conclusion.

In this case, sequencing the conversation, workflow, and decisions meant that the sales team could begin talking to the channel partners to make short-term decisions they needed to act on. At the same time, the internal product teams could begin working and have enough time to get answers to the larger questions in front of them. As the leader, the head of sales operations recognized how to organize and sequence these activities to improve the collaborative approach to developing the strategy flow.

Launching some activities, deferring others, and cueing up the next conversation, task, or decision as the active thread completes are all important because they keep the collaborative strategy creation process moving forward.

Nobody waits—not the world, not the competition, not your customers—for you to get it all right. Figuring out what needs to happen at what point will give people a sense of what is on the horizon, so they have enough time to learn and reflect and act with grace.

Be a Collaborative Leader

These seven responsibilities and their corresponding assignments—managing cadence, generating ideas, nurturing a safe culture, developing connections, satisficing, engaging the issues, and tracing the topography of the conversation, workflow, and decisions—are task-independent. Meaning that, when you do them, you are leading co-creators, not just a leader of any particular effort to solve a problem.

By enabling people to interact this way, you are helping them fill in the pervasive Air Sandwich that limits an organization’s success. As a leader, you will foster the necessary learning, discovery, debates, and discussions; provide the context; set the cadence; decide when to move on; and know what happens next. It’s a tough role, but it’s a fun one, because you get to help an entire crew of people bring their passion and ideas to the table to benefit the company.

And without someone managing these responsibilities, the collaboration process won’t work. While intentions can be good and people can aim to be collaborative, they need a way to participate, take on the tough topics, and still move forward quickly. The leader’s role as described in this chapter is central to the work of collaboration.

Sure, being the Chief of Answers is fun. But being a conductor of co-creators is even more fun. Somewhat like jazz, collaborative strategy is a structured yet improvisational performance. As the leader, you get to be the band arranger. The responsibility for how the performance is structured falls to you. And you get to invite the “players” to jump in at the right points. The quality of the “music” your ensemble creates will then be shaped by the stage you step on, what each musician brings to the piece, and how well you all co-create the future together. By taking on this role, you are enabling the organization to have more velocity in its ability to set and achieve direction.

Up to this point we’ve covered a lot of ground. Without changing the role each of us plays and how we lead, we can’t take on the tasks of collaborating well. For some of you who are already behaving collaboratively, you may already know the importance of the “how” in the business results. We are ready to apply what we’ve covered in a practical, roll-up-your-sleeves-and-get-dirty kind of way.

So let’s now turn our attention toward putting all of this into practice. Let’s explore how leaders and individuals can take their new understanding of roles and responsibilities and apply it to the phases of the collaborative strategy process. That’s next.

[1] Source for merger statistics: http://blogs.computerworld.com/node/255. Fifty-eight percent of mergers failed to reach the value goals set by top management. (1999 A.T.Kearney study of 115 transactions cited in the book After the Merger, published by Pearson.) Fifty-three percent of mergers failed to deliver their expected results. (2001 Booz Allen & Hamilton study of 78 deals.) Seventy percent of mergers failed to achieve expected revenue synergies. Twenty-five percent of merger execs overestimated the cost savings by at least 25%.

[2] Hans Grande was an incredibly humble guy who would have protested my honoring him in public like this. He passed away shortly after the integration effort. I share his story because he believed, like I do, that the way we work together matters and helps us create value. Thanks to Dave Burkett of Adobe for sharing his memorial notes. More of Hans’s story can be read here: http://www.haas.berkeley.edu/groups/pubs/calbusiness/winter2007/alumni06.html.