The plot of a presentation is its story line. A good plot has a beginning, a middle, and an end. As an audience, we like to be introduced to the presentation appropriately—we don’t want to jump right into the middle. We want to know where we’re going and what to expect. We want to travel an interesting road, not a boring, monotonous one. We want peaks and valleys, dangers and lulls; we want to be interested in the process. And when we’ve gotten to the end, we want to know we’re there.

In a good film, the first five minutes (and often less) tells us what to expect; we know whether it’s a thriller, romantic comedy, film noir, documentary, action/adventure, science fiction, etc. And this is important to us because our minds get emotionally prepared for what we are about to sit through.

And when the film/presentation starts winding down, we need to know that too. I’m sure you’ve seen movies that have two or three endings in a row—you think the zombie is dead and buried and the protagonists are safe when lo, up he pops out of the ground again. And again. It’s really annoying.

Plot also involves the story itself, the connection to the human in us. As you’re developing your talk, find ways to make visceral connections with your audience, if possible. You can do it with your visuals, your own manner of speaking, and the tale itself.

Have you ever noticed that a published book has a half-title page (often), a copyright page, a full title page, a dedication page, an introduction, perhaps a preface, and sometimes even more pages before you finally get to the actual book? This is not just a process of legal notifications—it’s the foreplay before you start reading. We enjoy that process.

A film works the same way—even if the film starts before the credits roll or it starts along with the credits, the first few minutes are still an introductory time, a setup, before we jump directly into the film. Think of your presentation in the same way.

I’ve seen too many slideshows where the first slide jumps right into the topic, sort of like opening a book and the very first page is Chapter One. Too often, the presenter has placed his introductory notes on the first page and reads them.

Think of your presentation as a story, even if you’re telling the story of how to create a business plan or how to get divorced amicably or how to read Chaucer. Let the minds of the audience members move into your emotional space appropriately. You are much more likely to carry them along with you if you’ve set the scene and they know where you’re going.

With this first slide, we jump right into the presentation. Remember, it doesn’t cost any extra to make more slides. Give me an introduction, ease me into it.

In this Keynote template, one of the slides has a holding space for a graphic, so let’s use that to show off a sample journal. Then walk me through it, one step/one slide at a time.

After you give me an introduction to the general concept, spend a minute to describe where we’re going. Whether it’s a sales pitch, a teaching lesson, a moment in history, or a corporate overview, let me know where you plan to take me and even give me an idea of how long this will take. You can feel what happens inside yourself when I tell you this is going to take fifteen minutes, or if I tell you it’s going to be two hours. I’m more likely to go with you for two hours if I know from the get-go to expect that. I’m even more willing if you give me a brief rundown of what we’re going to see along the way.

Before launching directly into Step 1, I’d like an overview of the entire process so I know what to expect, how long it will take, am I gonna get dirty, what will I end up with?

Not all presentations need images—many work perfectly well with simply text, especially if it’s nice-looking text. And a few presentations work just fine using only images while the presenter talks.

Most of the time, however, we use a combination of both text and images. One way to think of the two of these working together is to consider the text on the slides as the data; the visual images as the emotional impact. You might be telling me the statistics on the number of women impacted by microcredit in a certain part of Africa, while you show me a woman in Magnambougou with her goat herd and children.

As you choose images to go with your presentation, keep in mind the difference between data and emotion; combine the two wisely.

Whenever possible, try to show the human side of topics in your presentation. This is not so hard to do when you have ideas and charts and graphs that have to do with people; it’s more difficult to do when you’re teaching a class about NMR spectroscopy. So don’t force a human story into a topic where it doesn’t belong or where it might just complicate things, but if it does belong, take advantage of it.

For instance, do you have statistics about how many children go to kindergarten in Korea? Instead of just the dry data, find an image of Korean children going to school so we connect the human beings with the statistics. Try to include the emotional impact of a relevant image that embodies that data. But remember, don’t add arbitrary or useless or confusing images just to create some random emotional moment.

Your manner of speaking, your manner of telling your presentation, can bring people into your talk or put them to sleep. You must talk to your audience. Look at them. Watch their faces for signs of boredom or enlightenment or confusion and respond accordingly.

In a Shakespearean play, it is most often the bad guy who talks directly to the audience in a soliloquy. Interestingly, this technique is what makes us love those bad guys in an odd way—Richard iii, Edmund, Iago. Falstaff and Hamlet are not bad guys, but they have more soliloquies than any other characters in the canon and they are two of the most beloved of all. What Shakespeare knew is that by talking directly to the audience, we (the audience) develop a relationship with the speaker. Whether the speaker is a fat, cowardly realist or a ruthless murderer, we have a relationship and they bring us along with them. We want to go where they go and we want to follow them through their process.

Think of the storytelling you grew up with. Did your Grandma tell you a story and never include you in it, never look at you, never exclaim in wonder with you? Of course not. By drawing in your audience, you are more likely to get them on your side.

This can be true whether you are teaching the art of losing weight or of changing the world through green-energy automobiles or the quantitative analysis of molecular biophysics. Look at your audience, speak to them, listen to them—as one human to another—and they will come with you.

We hear a lot about this idea of creating your presentation as a “story.” Some people get a wee bit confused with this thought and think they should provide their entire presentation as a story or series of personal anecdotes.

One book I bought about giving presentations is told through the tale of two cavemen, an example of the idea of “story” taken to the extreme. To get the gist of the information I had to slog through silly baloney about cavemen creating presentations. “Oh Robin,” you say, “Enjoy the process, go along for the ride, be in the moment.” Personally, I would rather get to the point of what I need to know and save that precious time for talking to my kids, creating mosaic art, hiking across the desert. And then get back to work.

Yes, anecdotal true stories of the lives of people or animals or yourself can elucidate things—sometimes. Sometimes they just add unnecessary words and it’s annoying. It seems to be a fine line.

Many, many presentations can benefit by uncovering the human interest. But stories are not critical to every presentation. Guy Kawasaki (GuyKawasaki.com) has a 10-20-30 rule for entrepreneurs who pitch to venture capitalists: 10 slides, 20 minutes, 30-point type. He wants straight talk.

If the story you want to tell is perfectly germane to the topic, if it moves the presentation forward, if it has an important life lesson that is integral to your subject, and if it’s fascinating in some relevant way, go ahead and tell me. But be careful about making the presentation about you. I have seen presenters weave in their personal stories throughout an entire 60-minute presentation and what most of the audience comes away with is, “It’s all about him.”

Please understand that I am not denigrating the importance of story. I realize story is vitally important to the human race. When Prodigy did a study on how people used their Internet service after it had been out a year or two, they were surprised to discover that the overwhelming majority of people used it—not for business or trade or research—they used it to talk to each other, to listen to each other, to create relationships, to build stories.

I just encourage you to think long and hard about whether the personal stories you plan to include in your talk are about the information you are trying to communicate, or about you. Don’t confuse the focus of your presentation by including irrelevant personal stories.

Think of your favorite film and about how the pace varied throughout it: sometimes there’s a fast onslaught of an exciting happening, then a restful pause, then some more stuff that isn’t quite as exciting but it still moves the plot forward, then an intriguing slow moment, then a fast pace followed by another romantic pause. The story in your presentation can learn some lessons from films.

If you carry on through your presentation at the same pace, whether that pace is fast and furious or slow and thoughtful, it becomes monotonous. Consider how you can find some moments to breeze through half a dozen slides in thirty seconds, pause on one slide to discuss that topic for four minutes, show/discuss three slides in the next two minutes, stop on a slide for five minutes, open up a short discussion to the audience, etc. Vary your tone, move around, wave your arms, point your fingers, speak with authority and emotion. Remember that you are a human—don’t become a mere appendage to the slide.

I would bet that your presentation automatically arranges itself in a varied pace—you just need to be conscious of that pace and work with it. Don’t be afraid to show a few slides very quickly, even half a second per slide. In one of the screenwriting courses I’ve taken, the instructor showed a six-minute video clip of stills from hundreds of movies, shown for varying amounts of time. Some of the clips were only visible for a quarter of a second. The amazing thing was that our emotional minds instantly recognized the images—we knew who that was and which film, but our brains could not process it into words fast enough. It was kind of exhausting, not only because our pea-brains kept struggling to find the names and spew them out, but because each image evoked the entire movie, all the passion and hate and anxiety and tension and drama and love and humor. Images are so powerful.

So the point is that you can use explanatory imagery to skim through some parts of your presentation quickly—our minds absorb the images quickly enough. Slow down for other parts. Even words (in lowercase, not all capital letters) go into our brains instantly, so experiment with one or two words on slides that you skim through quickly. You’ll find all kinds of ways to vary the pace—you just need to be aware of the concept and work with it.

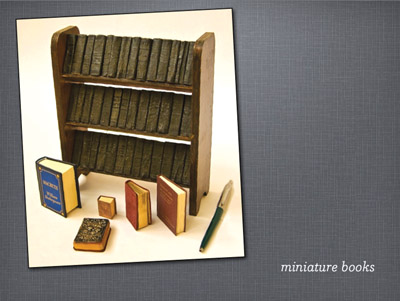

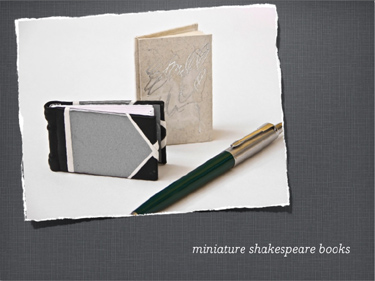

Consider this portion of a talk I gave to graphic design teachers and students on the trend in design to use handmade elements. I was relating it to my own journey in doing things with my hands again and how those things you’re interested in can lead to new ideas in your graphic design projects. The first six slides of this particular segment took about fifteen seconds, then we paused on the next two slides to talk about ways to incorporate images and text from old books into graphic design projects. (The template is from Keynote.)

“Several years ago I joined the Miniature Book Society and started collecting miniature books . . .

specifically miniature Shakespeare books . . .

specifically really crummy miniature Shakespeare books . . .

because I was also teaching myself the art of bookbinding to bind the 65 letters home . . .

from Europe that I had written in my early twenties into books for my kids . . .

and this process led to my collecting old, destroyed books whose pages can be used in a variety of ways in graphic design projects.”

Let the audience know when your presentation is over—don’t let them have to awkwardly figure it out because you stopped talking. Just as a story has an ending, let your presentation have an ending. As an audience, we need to have that closure—it sets off a certain cue in our minds. You know that feeling at a play or performance when the lights go off and you’re not sure if it’s the end or just a scene change so you don’t know whether or not to clap? We need the “. . . and they lived happily ever after” closing moment.

When you are close to the end, you might say something like, “I have one more point to make,” or “Let me say this before I close,” or “The final important thing to understand is . . . .” This sets us up, the audience, to tie it all together in our minds, get our questions ready, close our notebooks, and send one last tweet.

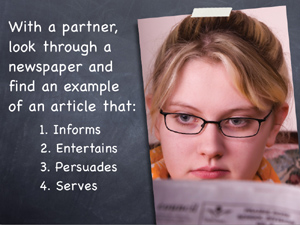

This is the last slide in a presentation for high school students about using the newspaper. Is it clear that this is the end? Not really—there’s no clue whether or not another task follows this one.

Even if the instructor says, “And here is your last task,” we still like a final opportunity to close the window. Give me a goodbye slide, please! End of story.

Then create a “Thank you” slide so there is no question that you are finished and they can applaud now. Or your slide might say, “Questions?” or “Applause Now” or “Thank goodness it’s over” or anything else appropriate and relevant. Because it’s your last slide and you haven’t used much animation throughout your presentation (except where entirely relevant, right?), feel free to use your favorite gaudy transition to this goodbye slide (as shown on the opposite page). It might wake up your audience.

Saying goodbye and thank you is the perfect time to use the most obnoxious transitions in your collection.

An audience, as you well know because you’ve been in an audience many a time, always appreciates the opportunity to ask questions at the end of a presentation, whether or not they actually ask any. I spent two days at a seminar given by a very famous communications guru who not only hated any sort of visual presentation so I don’t even remember nine-tenths of what he talked about (I don’t retain much of what goes in my ears), but he also refused to answer questions from the group. It made me feel like he was hiding something, like he didn’t want to be put on the spot about anything, sort of like the people who demo software at trade shows but refer all questions to the other people who actually know what they’re talking about.

So stand up and be honest—ask for questions. If you can’t field questions about your subject, you shouldn’t be talking about it. You might be in a situation where someone can catch tweets or other online questions for you; this is a great resource for people who are too shy to stand up in a crowd and ask. Obviously, there are some presentation situations where questions are not part of the program, but if it’s expected, rise to the occasion. If you ask for questions and there are none after about six seconds, say, “Thank you very much,” and leave the stage to thunderous applause.