DOMAIN 6

Legal, Risk, and Compliance

THE CLOUD OFFERS COMPANIES and individuals access to vast amounts of computing power at economies of scale only made possible by distributed architectures. However, those same distributed architectures can bring a unique set of risks and legal challenges to companies due to the geographic distribution of services the cloud provides. The cloud, powered by the Internet, flows freely across the borders of countries as information is stored in data centers worldwide and travels the globe. Determining what laws apply to cloud computing environments is an ongoing challenge, as in many situations, the company may be based in one country, host services in another, and be serving customers across the globe. In addition, the convenience and scalability offered by the cloud necessitates the acceptance of additional risks introduced by the reliance on a third-party provider.

ARTICULATING LEGAL REQUIREMENTS AND UNIQUE RISKS WITHIN THE CLOUD ENVIRONMENT

One indisputable fact that has arisen with cloud computing is that the legal and compliance efforts of computing have become more complex and time-consuming. With data and compute power spread across countries and continents, international disputes have dramatically increased. Hardly a day goes by without a news story about a conflict relating to violations of intellectual property, copyright infringements, and data breaches. These types of disputes existed well before the ascendence of cloud computing, but they have definitely become more commonplace and costly. It is in many ways the simplicity of cloud computing to have services span jurisdictions that has led to the marked increase in complexity of compliance. To prepare for these challenges, a cloud security professional must be aware of the legal requirements and unique risks presented by cloud computing architectures.

Conflicting International Legislation

With cloud technologies comes the inherent power to distribute computing across countries and continents. Though it is certainly possible to use the cloud on a local or regional scale through configuration or policy, many cloud customers use cloud services across regions and jurisdictions to provide redundancy and closer service delivery across the crowded Internet. So how do companies address the fact that their servers, customers, and physical locations may in fact be governed by completely separate sets of laws? It is a constant challenge that requires cloud security practitioners to be familiar with multiple sets of laws and when they might apply. Take, for instance, the law of the land in the European Union (the EU, a group of 27 European countries that share a common set of laws and economic policies). The EU is governed by data privacy laws known as the General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) that we will cover later in the chapter. Do these laws apply to U.S.-based companies doing business in the EU or with EU citizens? What about in situations where EU laws conflict with state and federal laws in the United States? Because of the international nature of cloud offerings and customers, cloud practitioners must be aware of multiple sets of laws and regulations and the risks introduced by conflicting legislation across jurisdictions. These conflicts may include the following:

- Copyright and intellectual property law, particularly the jurisdictions that companies need to deal with (local versus international) to protect and enforce their IP protections

- Safeguards and security controls required for privacy compliance, particularly details of data residency or the ability to move data between countries, as well as varying requirements of due care in different jurisdictions

- Data breaches and their aftermath, particularly breach notification

- International import/export laws, particularly technologies that may be sensitive or illegal under various international agreements

Craig Mundie, the former chief of Microsoft's research and strategy divisions, explained it in these terms:

People still talk about the geopolitics of oil. But now we have to talk about the geopolitics of technology. Technology is creating a new type of interaction of a geopolitical scale and importance… . We are trying to retrofit a governance structure which was derived from geographic borders. But we live in a borderless world.

In simple terms, a cloud security practitioner must be familiar with a number of legal arenas when evaluating risks associated with a cloud computing environment. The simplicity and inexpensive effort of configuring computing and storage capabilities across multiple countries and legal domains has led to a vast increase in the complexity of legal and compliance issues.

Evaluation of Legal Risks Specific to Cloud Computing

The cloud offers delivery and disaster recovery possibilities unheard of a few decades ago. Cloud service providers can offer content delivery options to host data within a few hundred miles of almost any human being on Earth. Customers are not limited by political borders when accessing services from cloud providers. However, the ability to scale across the Internet to hundreds of locations brings a new set of risks to companies taking advantage of these services. Storing data in multiple foreign countries introduces legal and regulatory challenges. Cloud computing customers may be impacted by one or more of the following legislative items:

- Differing legal requirements; for example, state laws in the United States requiring data breach notifications, which have varying timeframes and state-level reporting entities versus international with country-level reporting entities.

- Different legal systems and frameworks in different countries, such as legislation versus case law/precedent. A Certified Cloud Security Professional (CCSP) shouldn't be a master of all but should acquire advice from competent legal counsel.

- Challenges of conflicting law, such as EU GDPR and the U.S. CLOUD Act, one of which requires privacy and the other that mandates disclosure. A CCSP needs to be aware that these competing interests exist and may need to be used to drive business decisions (for example, corporate structure to avoid the conflict.)

Legal Frameworks and Guidelines That Affect Cloud Computing

Cloud security practitioners should be keenly aware of a number of legal frameworks that may affect the cloud computing environments they maintain. The following frameworks are the products of multinational organizations working together to identify key priorities in the security of information systems and data privacy.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) guidelines lay out privacy and security guidelines. (See www.oecd.org/sti/ieconomy/privacy-guidelines.htm.) The OECD guidelines are echoed in European privacy law in many instances. The basic principles of privacy in the OECD include the following:

- Collection limitation principle: There should be limits on the collection of personal data as well as consent from the data subject.

- Data quality principle: Personal data should be accurate, complete, and kept up-to-date.

- Purpose specification principle: The purpose of data collection should be specified, and data use should be limited to these stated purposes.

- Use limitation principle: Data should not be used or disclosed without the consent of the data subject or by the authority of law.

- Security safeguards principle: Personal data must be protected by reasonable security safeguards against unauthorized access, destruction, use, or disclosure.

- Openness principle: Policies and practices about personal data should be freely disclosed, including the identity of data controllers.

- Individual participation principle: Individuals have the right to know if data is collected on them, access any personal data that might be collected, and obtain or destroy personal data if desired.

- Accountability principle: A data controller should be accountable for compliance with all measures and principles.

In addition to the basic principles of privacy, there are two overarching themes reflected in the OECD: first, a focus on using risk management to approach privacy protection, and second, the concept that privacy has a global dimension that must be addressed by international cooperation and interoperability. The OECD council adopted guidelines in September 2015, which provide guidance in the following:

- National privacy strategies: Privacy requires a national strategy coordinated at the highest levels of government. CCSPs should be aware of the common elements of national privacy strategies based on the OECD suggestions and work to help their organizations design privacy programs that can be used across multiple jurisdictions. Additionally, a CCSP should be prepared to help their organization design a privacy strategy using business requirements that deliver a good cost-benefit outcome.

- Data security breach notification: Both the relevant authorities and the affected individual(s) must be notified of a data breach. CCSPs should be aware that multiple authorities may be involved in notifications and that the obligation to notify authorities and individuals rests with the data controller.

- Privacy management programs: These are operational mechanisms to implement privacy protection. A CCSP should be familiar with the programs defined in the OECD guidelines.

Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation Privacy Framework

The Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation Privacy Framework (APEC) is an intergovernmental forum consisting of 21 member economies in the Pacific Rim. (See www.aicpa.org/content/dam/aicpa/interestareas/informationtechnology/resources/privacy/downloadabledocuments/10252-346-records-management-pro.pdf.) The goal of this framework is to promote a consistency of approach to information privacy protection. This framework is based on nine principles.

- Preventing harm: An individual has a legitimate expectation of privacy, and information protection should be designed to prevent the misuse of personal information.

- Collection limitation: Collection of personal data should be limited to the intended purposes of collection and should be obtained by lawful and fair means with notice and consent of the individual. As an example, an organization running a marketing operation should not collect Social Security or national identity numbers, as they are not required for sending marketing materials.

- Notice: Information controllers should provide clear and obvious statements about the personal data that they are collecting and the policies around use of the data. This notice should be provided at the time of collection. You are undoubtedly familiar with the banners and pop-ups in use at many websites to notify users of what data is being collected.

- Use of personal information: Personal information collected should be used only to fulfill the purposes of collection and other compatible or related purposes except: a) with the consent of the individual whose personal information is collected; b) when necessary to provide a service or product requested by the individual; or, c) by the authority of law and other legal instruments, proclamations, and pronouncements of legal effect.

- Integrity of personal information: Personal information should be accurate, complete, and kept up-to-date to the extent necessary for the purposes of use.

- Choice and consent: Where appropriate, individuals should be provided with clear, prominent, easily understandable, accessible, and affordable mechanisms to exercise choice in relation to the collection, use, and disclosure of their personal information.

- Security safeguards: Personal information controllers should protect personal information that they hold with appropriate safeguards against risks, such as loss or unauthorized access to personal information or unauthorized destruction, use, modification, or disclosure of information or other misuses.

- Access and correction: Individuals should be able to obtain from the personal information controller confirmation of whether the personal information controller holds personal information about them, and have access to information held about them, challenge the accuracy of information relating to them, and have the information rectified, completed, amended, or deleted.

- Accountability: A personal information controller should be accountable for complying with measures. Companies must identify who is responsible for complying with these privacy principles.

General Data Protect Regulation

The General Data Protect Regulation (GDPR) is perhaps the most far-reaching and comprehensive set of laws ever written to protect data privacy. (See gdpr.eu/what-is-gdpr

.) In the EU, the GDPR mandates privacy for individuals, defines companies' duties to protect personal data, and prescribes punishments for companies violating these laws. GDRP fines for violating personal privacy can be massive at 20 million Euros or 4 percent of global revenue (whichever is greater). For this reason alone, a CCSP should be familiar with these laws and the effects that they have on any company operating within, housing data in, or doing business with citizens of these countries in the 27-nation bloc. GDPR became the law of the land in May 2018, and incorporated many of the same principles of the former EU Data Protection Directive.

GDPR identifies formally the role of the data subject, controller, and processor. The data subject is defined as an “identified or identifiable natural person,” or, more simply, a person. The GDPR draws a distinction between a data controller and a data processor to formally recognize that not all organizations involved in the use and processing of personal data have the same degree of responsibility.

- A data controller under GDPR determines the purposes and means of processing personal data.

- A data processor is the body responsible for processing the data on behalf of the controller.

In cloud environments, this is often separate companies, where a company may be providing services (the data controller) on a cloud provider (the data processor).

The GDPR is a massive set of regulations that covers almost 90 pages of details and is a daunting challenge to many organizations. A CCSP should be familiar with the broad areas of the law, but ultimately organizations should consult an attorney to ensure that operations are compliant. GDRP encompasses the following main areas:

- Data protection principles: If a company processes data, it must do so according to seven protection and accountability principles.

- Lawfulness, fairness, and transparency: Processing must be lawful, fair, and transparent to the data subject.

- Purpose limitation: The organization must process data for the legitimate purposes specified explicitly to the data subject when it was collected.

- Data minimization: The organization should collect and process only as much data as absolutely necessary for the purposes specified.

- Accuracy: The organization must keep personal data accurate and up-to-date.

- Storage limitation: The organization may store personally identifying data for only as long as necessary for the specified purpose.

- Integrity and confidentiality: Processing must be done in such a way as to ensure appropriate security, integrity, and confidentiality (for example, by using encryption).

- Accountability: The data controller is responsible for being able to demonstrate GDPR compliance with all of these principles.

- Data security: Companies are required to handle data securely by implementing appropriate technical measures and to consider data protection as part of any new product or activity.

- Data processing: GDPR limits when it is legal to actually process user data. There are very specific instances when this is allowed under the law.

- Consent: Strict rules are in place for how a user is to be notified that data is being collected.

- Personal privacy: The GDPR implements a litany of privacy rights for data subjects, which gives individuals far greater rights over their data that companies collect. This includes rights to be informed, access, rectify, restrict, obtain, and the much touted “right to be forgotten,” which allows the end user to request deletion of all personal data.

Additional Legal Controls

The cloud service provider has also significantly complicated the legal landscape when it comes to legal controls. The provider of the infrastructure, platform, or software as a service must be evaluated as an additional party when considering compliance. If a cloud provider is responsible for a violation of a legal control, the company can still be responsible for the legal ramifications. This applies to legal and contractual controls such as the following:

- Heath Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA): This 1996 U.S. law regulates the privacy and control of health information data.

- Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS): The current standard version 3.2 affects companies that accept, process, or receive electronic payments.

- Privacy Shield: This provides a voluntary privacy compliance framework through which companies can comply with portions of the GPDR in order to facilitate the movement of EU citizens' data into the United States by companies based in the United States. Note that this agreement is facing legal challenges in the EU.

- Sarbanes–Oxley Act (SOX): This law was enacted in 2002 and sets requirements for U.S. public companies to protect financial data when stored and used. It is intended to protect shareholders of the company as well as the general public from accounting errors or fraud within enterprises. This act specifically applies to publicly traded companies and is enforced by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). It is applicable to cloud practitioners in particular because it specifies what records must be stored and for how long, internal control reports, and formal data security policies.

- Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act (GBLA): U.S. federal law that requires financial institutions to explain how they share and protect their customers' private information.

Laws and Regulations

The cloud represents a dynamic and changing environment, and monitoring/reviewing legal requirements is essential to staying compliant. All contractual obligations and acceptance of requirements by contractors, partners, legal teams, and third parties should be subject to periodic review. When it comes to compliance, words have real meaning. You (and Microsoft Word's thesaurus) might think that the terms law and regulation are interchangeable, but when it comes to data privacy issues, they can have starkly different outcomes if they are not satisfied. Understanding the type of compliance that your company is subject to is vital to a CCSP. The outcome of noncompliance can vary greatly, including imprisonment, fines, litigation, loss of a contract, or a combination of these. To understand this landscape, a CCSP must first recognize the difference between data protected by legal regulations and data protected by contract.

- Statutory requirements are required by law.

- U.S. federal laws, such as HIPAA, GLBA, and SOX outlined in the previous section

- Additional federal laws such as the Family Education Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), which deals with privacy rights for students, and the Federal Information Security Management Act (FISMA), which protects federal data privacy

- State data privacy laws, which now exist in all 50 states as well as U.S. territories

- International laws, which we will discuss in a later section covering country-specific laws

- Regulatory requirements may also be required by law, but refer to rules issued by a regulatory body that is appointed by a government entity.

- In the United States, many regulatory examples exist, mostly dealing with contractor compliance to do business with the government. An example would be security requirements outlined by NIST that are necessary to handle government data (such as NIST 800-171).

- At the state level, several states use regulatory bodies to implement their cybersecurity requirements. One example is the New York State Department of Financial Services (NY DFS) cybersecurity framework for the financial industry (23 NYCRR 500).

- There are numerous international requirements dealing with cloud legal requirements (including APEC and GDPR).

- Contractual requirements are required by a legal contract between private parties. These are not laws, and breaching these requirements cannot result in imprisonment (but can result in financial penalties, litigation, and terminations of contracts). Common contractual compliance requirements include the following:

- Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS)

- Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA)

- Service Organization Controls (SOC)

- Generally Accepted Privacy Principles (GAPP)

- Center for Internet Security (CIS) Critical Security Controls (CSC)

- Cloud Security Alliance (CSA) Cloud Controls Matrix (CCM)

It is vital to consider the legal and contractual issues that apply to how a company collects, stores, processes, and ultimately deletes data. Few companies or entities have the luxury of not considering the important national and international laws that must be complied with to do business. Perhaps not surprisingly, company officers have a vested interest in complying with these laws. Laws and regulations are specific in who is responsible for the protection of information. Federal laws like HIPAA spell out that senior officers within a company are responsible for (and liable for) the protection of data. International regulations like GDPR and state regulations such as NYCRR 500 identify the role of a data protection officer or chief information security officer and outline their culpability for any data loss incident.

If you are using cloud infrastructure from a cloud provider, you the customer must impose all legal, regulatory, and contractual obligations that are imposed on you by relevant legislation onto your cloud provider. No matter who is hosting your data or services, you the customer are accountable for compliance of effective security controls and data security.

Forensics and eDiscovery in the Cloud

When a crime is committed, law enforcement or other agencies may perform eDiscovery using forensic practices to gather evidence about the crime that has been committed and to prosecute the guilty parties. eDiscovery is defined as any process in which electronic data is pursued, located, secured, and searched with the intent of using it as evidence in a civil or criminal legal case. In a typical eDiscovery case, computing data might be reviewed offline (with the equipment powered off or viewed with a static image) or online (with the equipment on and accessible). In the cloud environment, almost all eDiscovery cases will be done online due to the nature of distributed computing and the difficulty in taking those systems offline.

Forensics, especially cloud forensics, is a highly specialized field that relies on expert technicians to perform the detailed investigations required to adequately perform discovery while not compromising the potential evidence and chain of custody. In any forensic investigation, a CCSP can typically expect to work with an expert outside consultant or law enforcement personnel.

eDiscovery Challenges in the Cloud

For a security professional, the challenges of eDiscovery are greatly increased by the use of cloud technologies. If you received a call from an outside law enforcement agency (never a phone call that anyone likes to receive) about criminal activities on one of your servers in your on-premise data centers, you might immediately take that server offline in order to image it, always having the data firmly in your possession. Now imagine if the same service was hosted in a SaaS model in the cloud distributed across 100 countries using your content delivery network. Could you get the same data easily? Could you maintain possession, custody, or control of the electronically stored information? Who has jurisdiction in any investigation? Can a law enforcement agency compel you to provide data housed in another country? All of these questions make cloud eDiscovery a distinct challenge.

eDiscovery Considerations

When you’re considering a cloud vendor, eDiscovery should be considered during any contract negotiation phase. If you think about your cloud providers today, can you recall how many conversations you might have had with their support teams? Would you know who to contact if an investigation was needed?

To pose another question, do you actually know where the data is physically housed? Many companies make use of the incredible replication and fail-over technologies of the modern cloud, but that means data may be in different time zones, countries, or continents when an investigation is launched. As we have outlined, laws in one country or state may in fact clash or break with laws of another. It is the duty of the cloud security profession to exercise due care and due diligence in documenting and understanding to the best of their ability the relevant laws and statutes pertaining to an investigation prior to it commencing.

In some cases, proactive architectural decisions can simplify issues down the road. For example, if a company chooses to house customer data within their legally defined jurisdiction (for example, EU citizen data is always housed on cloud servers within the EU), it can simplify any potential investigations or jurisdictional arguments that might arise.

Conducting eDiscovery Investigations

Where there is a problem in technology, there is usually a solution, and the marketplace for eDiscovery tools has grown commensurately with the explosion in the use of cloud service providers. There are a healthy number of vendors that specialize in this area. For a CCSP, it is important to learn about eDiscovery actors when evaluating contracts and service level agreements (SLAs) to determine what forms of eDiscovery are permissible. These are the main types of investigatory methods:

- SaaS-based eDiscovery: Why not use the cloud to perform eDiscovery on the cloud? These tools from a variety of vendors are used by investigators and law firms to collect, preserve, and review data.

- Hosted eDiscovery: In this method, your hosting provider includes eDiscovery services in the contractual obligations that can be exercised when and if necessary. This may limit a customer to a preselected list of forensic solutions, as CSPs are often wary of customer-provided tools due to the potential for affecting other cloud customers during the process.

- Third-party eDiscovery: When there are no obligations in a contract, a third party may be contracted to perform eDiscovery operations. In this model, the CCSP must work especially closely with the third party to provide appropriate access to necessary resources in the cloud.

Cloud Forensics and Standards

As you can see, the forensic and eDiscovery requirements for many legal controls are greatly complicated by the cloud environment. Unlike on-premises systems, it can be difficult or impossible to perform physical search and seizure of cloud resources such as storage or hard drives. Standards from bodies such as the International Organization for Standardization (ISO)/International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) and the Cloud Security Alliance (CSA) provide guidance to cloud security practitioners on best practices for collecting digital evidence and conducting forensics investigations in cloud environments. CCSPs should be familiar with the following standards:

- Cloud Security Alliance: The CSA Security Guidance Domain 3: Legal Issues: Contracts and Electronic Discovery highlights some of the legal aspects raised by cloud computing. Of particular importance to CCSPs are the guidance provided on negotiating contracts with cloud service providers in regard to eDiscovery, searchability, and preservation of data.

- ISO/IEC 27037:2012: This provides guidelines for the handling of digital evidence, which include the identification, collection, acquisition, and preservation of data related to a specific case.

- ISO/IEC 27041:2014-01: This provides guidance on mechanisms for ensuring that methods and processes used in the investigation of information security incidents are “fit for purpose.” CCSPs should pay close attention to sections on how vendor and third-party testing can be used to assist with assurance processes.

- ISO-IEC 27042:2014-01: This standard is a guideline for the analysis and interpretation of digital evidence. A CCSP can use these methods to demonstrate proficiency and competence with an investigative team.

- ISO/IEC 27043: The security techniques document covers incident investigation principles and processes. This can help a CCSP as a “playbook” for many types of incidents, including unauthorized access, data corruption, system crashes, information security breaches, and other digital investigations.

- ISO/IEC 27050-1: This standard covers electronic discovery, the process of discovering pertinent electronically stored information involved in an investigation.

UNDERSTANDING PRIVACY ISSUES

The Internet age has brought with it an unprecedented amount of information flow. Knowledge (and cat videos) is shared by billions of Internet-connected humans at the speed of light around the world every day. The flow of information is two-way, however, and corporations and governments work hard to analyze how you interact with the Internet, both from your web activity as well as from your phone habits. Billions of consumers have installed listening devices in their homes (think Google Home and Amazon Alexa) and carry a sophisticated tracking device willingly on their person each and every day (the smart phone). All of this data allows better marketing investments as well as more customized recommendations for consumers.

With the advent of cloud computing, the facilities and servers used to store and process all of that user data can be located anywhere on the globe. To ensure availability and recoverability, it is good practice to ensure that data is available or at least backed up in multiple geographic zones to prevent loss due to widespread natural disasters such as an earthquake or hurricane. Indeed, in certain countries (like the tiny nation of Singapore at under 300 square miles), it would be impossible to protect from natural disasters without sending data to additional countries (and therefore legal jurisdictions).

Difference between Contractual and Regulated Private Data

In any cloud computing environment, the legal responsibility for data privacy and protection rests with the cloud consumer, who may enlist the services of a cloud service provider (CSP) to gather, store, and process that data. If your company uses Amazon Web Services (AWS) to host your website that gathers customer data, the responsibility for that data rests with you. You as the data controller are responsible for ensuring that the requirements for protection and compliance are met and that your contracts with the cloud service provider stipulate what requirements must be met by the CSP.

There are a number of terms that describe data that might be regulated or contractually protected. Personally identifiable information (PII) is a widely recognized classification of data that is almost universally regulated. PII is defined by the NIST standard 800-122 as “any information about an individual maintained by an agency, including (1) any information that can be used to distinguish or trace an individual‘s identity, such as name, social security number, date and place of birth, mother‘s maiden name, or biometric records; and (2) any other information that is linked or linkable to an individual, such as medical, educational, financial, and employment information.” (See nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/Legacy/SP/nistspecialpublication800-122.pdf.)

Protected health information (PHI) was codified under the HIPAA statutes in 1996. Any data that might relate to a patient's health, treatment, or billing that could identify a patient is PHI. When this data is electronically stored, it must be secured using best practices, such as unique user accounts for every user, strong passwords and MFA, principles of least privilege for accessing PHI data, and auditing all access and changes to a patient's PHI data.

Table 6.1 outlines types of regulated private data and how they differ.

TABLE 6.1 Types of Regulated Data

| DATA TYPE | DEFINITION |

|---|---|

| Personally identifiable information (PII) | Personally identifiable information is information that, when used alone or with other relevant data, can identify an individual. PII may contain direct identifiers (such as SSN numbers) that can identify a person uniquely, or quasi-identifiers (such as race) that can be combined with other quasi-identifiers (such as date of birth) to successfully recognize an individual. |

| Protected health information (PHI) | Protected health information, also referred to as personal health information, generally refers to demographic information, medical histories, test and laboratory results, mental health conditions, insurance information, and other data that a healthcare professional collects to identify an individual and determine appropriate care. |

| Payment data | Bank and credit card data used by payment processors in order to conduct point-of-sale transactions. |

There are two main types of regulated private data that we will discuss in further detail.

Contractual Private Data

When your organization collects, processes, transmits, or stores private data as part of normal business processes, the information must be protected according to relevant laws and regulations. If an organization outsources any of those functions to a third party such as a cloud service provider, the contracts must specify what the applicable rules and requirements are and what laws that the cloud service provider must adhere to.

For example, if a company is handling PHI that must be processed within the United States, any contracts with a CSP must clearly specify that fact. It is the obligation of the data owner to make all terms and conditions clear and transparent for the outsourcing contract.

Regulated Private Data

The biggest differentiator between contractual and regulated data is that regulated data must be protected under legal and statutory requirements, while contractual data is protected by legal agreements between private parties. Both PII and PHI data are subject to regulation, and the disclosure, loss, or altering of these data can subject a company (and individuals) to statutory penalties including fines and imprisonment. In the United States, protection of PHI data is required by HIPAA, which provides requirements and penalties for failing to meet obligations.

Regulations are put into place by governments and government-empowered agencies to protect entities and individuals from risks. In addition, they force providers and processors to take appropriate measures to ensure protections are in place while identifying penalties for lapses in procedures and processes.

One of the major differentiators between contracted and regulated privacy data is in breach reporting. A data breach of regulated data (or unintentional loss of confidentiality of data through theft or negligence) is covered by myriad state and federal laws in the United States. There are now data privacy laws covering PII in all 50 states, with legislative changes happening every year. Some states have financial penalties of as little as $500 for data privacy violations, while others have fines in the hundreds of thousands of dollars as well as prison time for company officers. The largest state fine for a data privacy breach was handed to Uber for a 2016 breach and totaled over $148 million dollars in fines to the state of California.

Components of a Contract

As we have detailed, the outsourcing of services to a cloud service provider in no way outsources the risk to the company as the data owner. A CCSP must be familiar with key concepts when contracting with cloud service providers to ensure that both parties understand the scope and provisions when private data is concerned. Key contract areas include the following:

- Scope of data processing: The provider must have a clear definition of the permitted forms of data processing. For example, data collected on user interactions for a cloud customer should not be used by the CSP to inform new interface designs.

- Subcontractors: It is important to know exactly where all processing, transmission, storage, and use of data will take place and whether any part of the process might be undertaken by a subcontractor to the cloud service provider. If a subcontractor will be used in any phase of data handling, it is vital that the customer is contractually informed of this development.

- Deletion of data: How data is to be removed or deleted from a cloud service provider is important and helps protect against unintentional data disclosure. In the old days, data was often physically destroyed (with a screwdriver through a hard drive). In the cloud environment, that is next to impossible, so contracts must spell out the methods that data is to be securely removed from any environment (and subcontractor environment). One example is cryptoshredding, or rendering data inaccessible by cryptographic methods.

- Data security controls: If data requires a level of security controls when it is processed, stored, or transmitted, that same level of security control must be ensured in a contract with a cloud service provider. Ideally, the level of data security controls would exceed what is required (as is often the case for cloud service providers). Typical security controls include encryption of data while in transit and while at rest, access control and auditing, layered security approaches, and defense-in-depth measures.

- Physical location of data: Knowledge of the physical location of where data is stored and processed (and, in some cases, transferred) is vital to ensure compliance with legal and regulatory requirements. Contractually indicating what geographic locations are acceptable for data storage and processing (and failover/backup) can protect a company from falling victim to unintended legal consequences. In addition to the location of the data, it is important to consider the location of the cloud service provider's offices and the offices of any subcontractors in use.

- Return or surrender of data: How does one break up with a cloud service provider? They know a lot about you, and they have your data. It is important to include in any contract the termination agreements, which should specify how and how quickly data is to be returned to the data owner. In addition, the contract should outline how returned data is ensured to be removed from the cloud service provider's infrastructure. Cloud data destruction standards should be identified when entering into a contract to ensure that methods are standardized and documented when data is returned or destroyed.

- Audits: Right to audit clauses should be included to allow a data owner or an independent consultant to audit compliance to any of the areas identified earlier. In practice, most CSPs will agree to be bound by standardized audit reports such as SOC 2 or ISO 27001, and most contracts specify the frequency that these reports must be produced.

Country-Specific Legislation Related to Private Data

If by now you're sensing a theme that data privacy is a complicated problem, it's about to get reinforced. An individual's right to privacy (and therefore their right to have their data handled in a secure and confidential way) varies widely by country and culture. As a result, the statutory and regulatory obligations around data privacy are vastly different depending on the citizenship of a data subject, the location of data being stored, the jurisdiction of the data processor, and even multinational agreements in place that may require data disclosure to government entities upon request.

There are many different attitudes and expectations of privacy in countries around the world. In some more authoritarian regimes, the data privacy rights of the individual are almost nonexistent. In other societies, data privacy is considered a fundamental right. Let's take a look around the world to examine some of the differences in data privacy around the globe.

The European Union (GDPR)

The 27-member EU serves as the bellwether for personal privacy in the developed world. The right to personal and data privacy is relatively heavily regulated and actively enforced in Europe, and it is enshrined into European law in many ways. In Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), a person has a right to a “private and family life, his home and his correspondence,” with some exceptions. Some additional types of private data under the GDPR include information such as race or ethnic origin, political affiliations or opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, and information regarding a person's sex life or sexual orientation.

In the European Union, PII covers both facts and opinions about an individual. Individuals are guaranteed certain privacy rights as data subjects. Significant areas of Chapter 3 of the GDPR (see gdpr.eu/tag/chapter-3) include the following on data subject privacy rights:

- The right to be informed

- The right of access

- The right to rectification

- The right to erasure (the so-called “right to be forgotten”)

- The right to restrict processing

- The right to data portability

- The right to object

- Rights in relation to automated decision-making and profiling

Australia

Australian privacy law was revamped in 2014, with an increased focus on the international transfer of PII. (See www.oaic.gov.au/privacy/australian-privacy-principles.)

Current law in Australia, under the Australian Privacy Act, allows for the offshoring of data but requires the transferring entity (the data processor) to ensure that the receiver of the data holds and processes it in accordance with the principles of Australian privacy law. As discussed in the previous section, this is commonly achieved through contracts that require recipients to maintain or exceed privacy standards. An important consequence under Australian privacy law is that the entity transferring the data out of Australia remains responsible for any data breaches by or on behalf of the recipient entities, meaning significant potential liability for any company doing business in Australia under current rules.

The United States

Data privacy laws in the United States generally date back to fair information practice guidelines that were developed by the precursor to the Department of Health & Human Services (HHS). (See Ware, Willis H. (1973, August). “Records, Computers and the Rights of Citizens,” Rand. Retrieved from www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/papers/2008/P5077.pdf.) These principles include the following concepts:

- For all data collected, there should be a stated purpose.

- Information collected from an individual cannot be disclosed to other organizations or individuals unless specifically authorized by law or by consent of the individual.

- Records kept on an individual should be accurate and up-to-date.

- There should be mechanisms for individuals to review data about them, to ensure accuracy. This may include periodic reporting.

- Data should be deleted when it is no longer needed for the stated purpose.

- Transmission of personal information to locations where “equivalent” personal data protection cannot be assured is prohibited.

- Some data is too sensitive to be collected unless there are extreme circumstances (such as sexual orientation or religion).

Perhaps the defining feature of U.S. data privacy law is its fragmentation. There is no overarching law regulating data protection in the United States. In fact, the word privacy is not included in the U.S. Constitution. However, there are now data privacy laws in each of the 50 states as well as U.S. territories.

There are few restrictions on the transfer of PII or PHI out of the United States, a fact that makes it relatively easy for companies to engage cloud providers and store data in other countries. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and other regulatory bodies do hold companies accountable to U.S. laws and regulations for data after it leaves the physical jurisdiction of the United States. U.S.-regulated companies are liable for the following:

- Personal data exported out of the United States

- Processing of personal data by subcontractors based overseas

- Projections of data by subcontractors when it leaves the United States

Several important international agreements and U.S. federal statutes deal with PII. The Privacy Shield agreement is a framework that regulates the transatlantic movement of PII for commercial purposes between the United States and the European Union. Federal laws worth review include HIPAA, GLBA, SOX, and the Stored Communications Act, all of which impact how the United States regulates privacy and data. At the state level, it is worth reviewing the California Consumer Protection Act (CCPA), the strongest state privacy law in the nation.

Privacy Shield

Unlike the GDPR, which is a set of regulations that affect companies doing business in the EU or with citizens of the EU, Privacy Shield is an international agreement between the United States and the European Union that allows the transfer of personal data from the European Economic Area (EEA) to the United States by US-based companies. (See www.impact-advisors.com/security/eu-us-privacy-shield-framework/ and iapp.org/media/pdf/resource:center/Comparison-of-Privacy-Shield-and-the-Controller-Processor-Model.pdf.) This agreement replaced the previous safe harbor agreements, which were invalidated by the European court of justice in October 2015. The Privacy Shield agreement is currently facing legal challenge in European Union courts as of July 2020. Adherence to Privacy Shield does not make U.S. companies GDPR-compliant. Rather, it allows the company to transfer personal data out of the EEA into infrastructure hosted in the United States.

To transfer data from the EEA, U.S. organizations can self-certify to the Department of Commerce and publicly commit to comply with the seven principles of the agreement. Those seven principles are as follows:

- Notice: Organizations must publish privacy notices containing specific information about their participation in the Privacy Shield Framework; their privacy practices; and EU residents' data use, collection, and sharing with third parties.

- Choice: Organizations must provide a mechanism for individuals to opt out of having personal information disclosed to a third party or used for a different purpose than that for which it was provided. Opt-in consent is required for sharing sensitive information with a third party or its use for a new purpose.

- Accountability for onward transfer: Organizations must enter into contracts with third parties or agents who will process personal data for and on behalf of the organization, which require them to process or transfer personal data in a manner consistent with the Privacy Shield principles.

- Security: Organizations must take reasonable and appropriate measures to protect personal data from loss, misuse, unauthorized access, disclosure, alteration, and destruction, while accounting for risks involved and nature of the personal data.

- Data integrity and purpose limitation: Organizations must take reasonable steps to limit processing to the purposes for which it was collected and ensure that personal data is accurate, complete, and current.

- Access: Organizations must provide a method by which the data subjects can request access to and correct, amend, or delete information the organization holds about them.

- Recourse, enforcement, and liability: This principle addresses the recourse for individuals affected by noncompliance, consequences to organizations for noncompliance, and compliance verification.

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996

The HIPAA legislation of 1996 defined what comprises personal health information, mandated national standards for electronic health record keeping, and established national identifiers for providers, insurers, and employers. Under HIPAA, PHI may be stored by cloud service providers provided that the data is protected in adequate ways.

The Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act (GLBA) of 1999

This U.S. federal law requires financial institutions to explain how they share and protect their customers' private information. GLBA is widely considered one of the most robust federal information privacy and security laws. This act consists of three main sections:

- The Financial Privacy Rule, which regulates the collection and disclosure of private financial information

- The Safeguards Rule, which stipulates that financial institutions must implement security programs to protect such information

- The Pretexting provisions, which prohibit the practice of pretexting (accessing private information using false pretenses)

The act also requires financial institutions to give customers written privacy notices that explain their information-sharing practices. GLBA explicitly identifies security measures such as access controls, encryption, segmentation of duties, monitoring, training, and testing of security controls.

The Stored Communication Act of 1986

The Stored Communication Act (SCA), as enacted as Title II of the Electronic Communication Privacy Act, created privacy protection for electronic communications (such as email or other digital communications) stored on the Internet. In many ways, this act extends the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution—the people's right, to be “secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures”—to the electronic landscape. It outlines that private data is protected from unauthorized access or interception (by private parties or the government).

The California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018

It may seem odd to talk about a state privacy law in the context of international privacy protection, but the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) is at present the strongest data privacy law in the United States. The act is intended to protect within state law the rights of a California citizen to the following:

- Know what personal data is being collected about them

- Know whether their personal data is sold or disclosed and to whom

- Opt out of the sale of personal data

- Access their personal data

- Request a business to delete any personal information about a consumer collected (the right to be forgotten)

- Be protected from discrimination (by service or price) for exercising their privacy rights

The CCPA outlines what entities need to comply with the law, the responsibility and accountability of the law's provisions, and the sanctions and fines that may be levied for violations of the law. Those fines can vary between $100 to $750 per consumer per data incident (or actual damages, whichever is greater), which makes the CCPA the most stringent privacy law in the United States.

Jurisdictional Differences in Data Privacy

As you have seen, this small review of different locations, jurisdictions, and legal requirements for the protection of private data demonstrates the challenge of maintaining compliance while using global cloud computing resources. Different laws and regulations may apply depending on the location of the data subject, the data collector, the cloud service provider, subcontractors processing data, and the company headquarters of any of the entities involved. A CCSP should always be aware of the issues in these areas and consult with legal professionals during the construction of any cloud-based services contract.

Legal concerns can prevent the utilization of a cloud services provider, add to costs and time to market, and significantly complicate the technical architectures required to deliver services. Nevertheless, it is vital to never replace compliance with convenience when evaluating services. In 2020, the video conferencing service Zoom was found to be engaged in the practice of routing video calls through servers in China in instances when no call participants were based there. This revelation caused an uproar throughout the user community and led to the abandonment of the platform by many customers out of privacy concerns. (See www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/apr/24/uk-government-told-not-to-use-zoom-because-of-china-fears.) In this example, customers abandoned the platform in large numbers because their data would certainly not enjoy the same privacy protections within China as would be expected in most liberal democracies.

Standard Privacy Requirements

With so many concerns and potential harm from privacy violations, entrusting data to any cloud provider can be daunting for many companies. Fortunately, there are industry standards in place that address the privacy aspects of cloud computing for customers. International organizations such as ISO/IEC have codified privacy controls for the cloud. ISO 27018 was published in July 2014, as a component of the ISO 27001 standard and was most recently updated in 2019. A CCSP can use the certification of ISO 27000 compliance as assurance of adherence to key privacy principles. Major cloud service providers such as Microsoft, Google, and Amazon maintain ISO 27000 compliance, which include the following key principles:

- Consent: Personal data obtained by a CSP may not be used for marketing purposes unless expressly permitted by the data subject. A customer should be permitted to use a service without requiring this consent.

- Control: Customers shall have explicit control of their own data and how that data is used by the CSP.

- Transparency: CSPs must inform customers of where their data resides and any subcontractors that might process personal data.

- Communication: Auditing should be in place, and any incidents should be communicated to customers.

- Audit: Companies must subject themselves to an independent audit on an annual basis.

Privacy requirements outlined by ISO 27018 enable cloud customers to trust their providers. A CCSP should look for ISO 27018 compliance in any potential provider of cloud services.

Generally Accepted Privacy Principles

Generally Accepted Privacy Principles (GAPP) consists of 10 principles for privacy from the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). (See www.aicpa.org/content/dam/aicpa/interestareas/informationtechnology/resources/privacy/downloadabledocuments/10252-346-records-management-pro.pdf.) The GAPP is a strong set of standards for the appropriate protection and management of personal data. The 10 main privacy principle groups consist of the following:

- Management: The organization defines, documents, communicates, and assigns accountability for its privacy policies and procedures.

- Notice: The organization provides notice of its privacy policies and procedures. The organization identifies the purposes for which personal information is collected, used, and retained.

- Choice and consent: The organization describes the choices available to the individual. The organization secures implicit or explicit consent regarding the collection, use, and disclosure of the personal data.

- Collection: Personal information is collected only for the purposes identified in the notice (see “Notice,” earlier in the list).

- Use, retention, and disposal: The personal information is limited to the purposes identified in the notice the individual consented to. The organization retains the personal information only for as long as needed to fulfill the purposes or as required by law. After this period, the information is disposed of appropriately and permanently.

- Access: The organization provides individuals with access to their personal information for review or update.

- Disclosure to third parties: Personal information is disclosed to third parties only for the identified purposes and with implicit or explicit consent of the individual.

- Security for privacy: Personal information is protected against both physical and logical unauthorized access.

- Quality: The organization maintains accurate, complete, and relevant personal information that is necessary for the purposes identified.

- Monitoring and enforcement: The organization monitors compliance with its privacy policies and procedures. It also has procedures in place to address privacy-related complaints and disputes.

Standard Privacy Rights Under GDPR

In the EU, the GDPR codifies specific rights of the data subject that must be adhered to by any collector or processor of data. These rights are outlined in Chapter 3 of the GDPR (Rights of the Data Subject) and consist of 12 articles detailing those rights:

- Transparent information, communication, and modalities for the exercise of the rights of the data subject

- Information to be provided where personal data are collected from the data subject

- Information to be provided where personal data have not been obtained from the data subject

- Right of access by the data subject

- Right to rectification

- Right to erasure (“right to be forgotten”)

- Right to restriction of processing

- Notification obligation regarding rectification or erasure of personal data or restriction of processing

- Right to data portability

- Right to object

- Automated individual decision-making, including profiling

- Restrictions

The complete language for the GDPR data subject rights can be found at gdpr.eu/tag/chapter-3

.

UNDERSTANDING AUDIT PROCESS, METHODOLOGIES, AND REQUIRED ADAPTATIONS FOR A CLOUD ENVIRONMENT

The word audit can strike a nerve of terror in many IT professionals (and in the context of the IRS, most taxpayers as well). Even in simple IT architectures, the audit process can consist of rigorous, time-consuming efforts that must be followed exactly. Auditing in a cloud environment presents some additional challenges when compared to traditional on-premises requirements. This section will detail some of the controls, impacts, reports, and planning processes for a cloud environment.

It is important for cloud professionals to work in concert with other key areas of the business to successfully navigate the journey to and in cloud computing. Since the cloud can be utilized and affect so many departments within an organization, it is vital to coordinate efforts with legal counsel, compliance, finance, and executive leadership.

One key resource for navigating the challenges of cloud compliance that all CCSPs should be familiar with is the Cloud Controls Matrix (CCM) provided by the Cloud Security Alliance (CSA). As of this writing, version 4.0 of the CCM (updated August 2019) provides some of the latest guidance in the form of a “Rosetta Stone” mapping control domains to dozens of relevant compliance specifications, including HIPAA, GAPP, FERPA, FedRAMP, ISO 27001, ITAR, NIST, and many others. This free resource gives cloud practitioners a comprehensive list of control domains, best-practice guidance in control specifications, relevant architectures, delivery models, and supplier relationships, as well as direct mappings to each of the compliance specifications. CCSPs should make use of this resource whenever they’re conducting an assessment of a cloud service provider or designing a compliant architecture in the cloud.

Internal and External Audit Controls

Internal audit and compliance have a key role in helping to manage and assess risk for both a cloud customer and provider. An organization may choose to keep internal audit functions within the company or outsource this function to a consultant or outside party.

Internal audit is an important line of defense for an organization. Many times, audits uncover issues with security or governance practices that can be corrected before more serious issues arise.

An internal auditor acts as a “trusted advisor” as an organization takes on new risks. In general, this role works with IT to offer a proactive approach with a balance of consultative and assurance services. An internal auditor can engage with relevant stakeholders to educate the customer to cloud computing risks (such as security, privacy, contractual clarity, Business Continuity Planning (BCP) and Disaster Recovery Planning (DRP) compliance with legal and jurisdictional issues). An internal audit also helps mitigate risk by examining cloud architectures to provide insights into an organization's cloud governance, data classifications, identity and access management effectiveness, regulatory compliance, privacy compliance, and cyber threats to a cloud environment.

It is desirable for an internal auditor to maintain independence from both the cloud customer and the cloud provider. The auditor is not “part of the team” but rather an independent entity who can provide facts without fear of reprisals or political blowback. An addition to the advisory role, an internal auditor will generally perform audits in the traditional sense, making sure the cloud systems meet contractual and regulatory requirements and that security and privacy efforts are effective.

Security controls may also be evaluated by external auditors. An external auditor definition does not work for the firm being audited. An external audit can be required by various pieces of financial legislation as well as information security standards such as ISO 27001. An external auditor is focused on ensuring compliance and therefore does not take on the role of a “trusted advisor” but rather more of regulator with punitive capability.

Impact of Audit Requirements

The requirement to conduct audits can have a large procedural and financial impact on a company. In a cloud computing context, the types of audit required are impacted largely by a company's business sector, the types of data being collected and processed, and the variety of laws and regulations that these business activities subject a company to. Some entities operate in heavily regulated industries subject to numerous auditing requirements (such as banks or chemical companies). Others may be brokers of data from international data subjects (such as big tech companies like Facebook, Google, and Microsoft).

Due to the changing nature of the cloud environment, auditors must rethink some traditional methods that have been used to collect evidence to support an audit. Consider the problems of data storage, virtualization, and dynamic failover.

- Is a data set representative of the entire user population? Cloud computing allows for the relatively easy distribution of data to take advantage of geographic proximity to end users, so obtaining a holistic representative sample may be difficult.

- Physical servers are relatively easy to identify and locate. Virtualization adds a layer of challenge in ensuring that an audited server is, in fact, the same system over time.

- Dynamic failover presents additional challenge to auditing operations for compliance to a specific jurisdiction.

Identity Assurance Challenges of Virtualization and Cloud

The cloud is fundamentally based in virtualization technologies. Abstracting the physical servers that power the cloud from the virtual servers that provide cloud services allows for the necessary dynamic environments that make cloud computing so powerful. Furthermore, the underlying virtualization technologies that power the cloud are changing rapidly. Even a seasoned systems administrator that has worked with VMware or Microsoft's Hyper-V may struggle with understanding the inherent complexity of mass scalable platforms such as AWS, Google, or Azure cloud.

Identity assurance in a computing context is the ability to determine with a level of certainty that the electronic credential representing an entity (whether that be a human or a server) can be trusted to actually belong to that person. As Peter Steiner famously captured in The New Yorker, “On the internet, nobody knows that you're a dog.” Bots and cyber criminals make identity assurance for end users much more difficult. The cloud greatly increases the difficulty of assurance for machines.

Depending on the cloud architecture employed, a cloud security professional must now perform multiple layers of auditing (of both the hypervisor and the virtual machines themselves) to obtain assurance. It is vital for any cloud security to understand the architecture that a cloud provider is using for virtualization and ensure that both hypervisors and virtual host systems are hardened and up-to-date. Change logs are especially important in a cloud environment to create an audit trail as well as an alerting mechanism for identifying when systems may have been altered in inappropriate ways by accidental or intentional manners.

Types of Audit Reports

Any audit, whether internal or external, will produce a report focused either on the organization or on the organization's relationship with an outside entity or entities. In a cloud relationship, oftentimes the ownership of security controls designed to reduce risk resides with a cloud service provider. An audit of the cloud service provider can identify if there are any gaps between what is contractually specified and what controls the provider has in place.

Service Organization Controls

The American Institute of CPAs (AICPA) provides a suite of offerings that may be used to report on services provided by a service organization that customers can use to address risks associated with an outsourced service. See Table 6.2.

TABLE 6.2 AICPA Service Organization Control Reports

Table source: www.aicpa.org

| REPORT | USERS | CONCERNS | DETAILS REQUIRED |

|---|---|---|---|

| SOC 1 | User entities and the CPAs that audit their financial statements | Effect of the controls at the service organization on the user entities' financial statements | Systems, controls, and tests performed by the service auditor and results of tests. |

| SOC 2 | Broad range of users that need detailed information and assurance about controls | Security, availability, and processing integrity of the systems the service organization uses to process users' data and the confidentiality and privacy of the information processed by these systems | Systems, controls, and tests performed by the service auditor and results of tests. |

| SOC 3 | Broad range of users that need detailed information and assurance about controls but do not have the need for or knowledge to make effective use of SOC 2 reports | Security, availability, and processing integrity of the systems the service organization uses to process users' data and the confidentiality and privacy of the information processed by these systems | Referred to as a “Trust Services Report,” SOC 3 reports are general used and can be freely distributed. |

The differences between the SOC reports are as follows:

- Service Organizations Controls 1 (SOC 1): These reports deal mainly with financial controls and are intended to be used primarily by CPAs that audit an entity's financial statements.

- SOC for Service Organizations: Trust Services Criteria (SOC 2): Report on Controls at a Service Organization Relevant to Security, Availability, Processing Integrity, Confidentiality, or Privacy. These reports are intended to meet the needs of a broad range of users that need detailed information and assurance about the controls at a service organization relevant to security, availability, and processing integrity of the systems the service organization uses to process users' data and the confidentiality and privacy of the information processed by these systems. These reports can play an important role in the following:

- Organizational oversight

- Vendor management programs

- Internal corporate governance and risk management processes

- Regulatory oversight

There are two types of reports for these engagements:

- Type 1: Report on the fairness of the presentation of management's description of the service organization's system and the suitability of the design of the controls to achieve the related control objectives included in the description as of a specified date.

- Type 2: Report on the fairness of the presentation of management's description of the service organization's system and the suitability of the design and operating effectiveness of the controls to achieve the related control objectives included in the description throughout a specified period.

- Service Organization Controls 3 (SOC 3): Similar to SOC 2, the SOC 3 report is designed to meet the needs of users who need the same types of knowledge offered by the SOC 2, but lack the detailed background required to make effective use of the SOC 2 report. In addition, SOC 3 reports are considered general use and can be freely distributed, as sensitive details have been removed and only general opinions and nonsensitive data are contained.

AICPA definitions of SOC controls can be found at the following locations:

- SOC 1:

www.aicpa.org/interestareas/frc/assuranceadvisoryservices/aicpasoc1report.html - SOC 2:

www.aicpa.org/interestareas/frc/assuranceadvisoryservices/aicpasoc2report.html - SOC 3:

www.aicpa.org/interestareas/frc/assuranceadvisoryservices/aicpasoc3report.html

The Statement on Standards for Attestation Engagements (SSAE) is a set of standards defined by the AICPA to be used when creating SOC reports. The most current version (SSAE 18) was made effective in May 2017, and added additional sections and controls to further enhance the content and quality of SOC reports.

The international counterpart of the AICPA, the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board, issues the International Standard on Assurance Engagements (ISAE). There are a number of differences between the two standards, and a security professional should always consult the relevant business departments to determine which audit report(s) will be used when assessing cloud systems.

Cloud Security Alliance

The Cloud Security Alliance (CSA) offers a Security Trust Assurance and Risk (STAR) certification that can be used by cloud service providers, cloud customers, or auditors and consultants to ensure compliance to a desired level of assurance. (See downloads.cloudsecurityalliance.org/assets/research/security-guidance/security-guidance-v4-FINAL.pdf.) STAR consists of three levels of certification:

- Level 1: Self-Assessment is a complimentary offering that documents the security controls provided by various cloud computing offerings, helping users assess the security of cloud providers they currently use or are considering using.

- Level 2: Attestation is a collaboration between CSA and the AICPA to provide guidelines for CPAs to conduct SOC 2 engagements using criteria from the AICPA (Trust Service Principles, AT 101) and the CSA Cloud Controls Matrix. STAR Attestation provides for rigorous third-party independent assessments of cloud providers.

- Level 3: Continuous monitoring through automated processes that ensure security controls are monitored and validated at all times.

Restrictions of Audit Scope Statements

Audits are a fact of life to ensure compliance and prevent sometimes catastrophic effects of security failures. Though no employee relishes the thought of undergoing an audit, they are somewhat of a necessary evil to ensure that risks are adequately controlled and compliance is met. Any audit must be appropriately scoped to ensure that both the client and the auditor understand what is in the audit space and what is not. This is almost always driven by the type of report being prepared. An audit scope statement would generally include the following:

- Statement of purpose and objectives

- Scope of audit and explicit exclusions

- Type of audit

- Security assessment requirements

- Assessment criteria and rating scales

- Criteria for acceptance

- Expected deliverables

- Classification (for example, secret, top secret, public, etc.)

Any audit must have parameters set to ensure the efforts are focused on relevant areas that can be effectively audited. Setting these parameters for an audit is commonly known as the audit scope restrictions. Why limit the scope of an audit? Audits are expensive endeavors that can engage highly trained (and highly paid) content experts. In addition, the auditing of systems can affect system performance and, in some cases, require the downtime of production systems.

Scope restrictions can be of particular importance to security professionals. They can spell out the operational components of an audit, such as the acceptable times and time periods (for example, days and hours of the week) as well as the types of testing that can be conducted against which systems. Carefully crafting scope restrictions can ensure that production systems are not impacted adversely by an auditor's activity. Additionally, audit scope statements can be used to clearly define what systems are subject to audit. For example, an audit on HIPAA compliance would only include systems that process and store PHI.

Gap Analysis

As a precursor to a formal audit process, a company may engage in a gap analysis to help identify potential trouble areas to focus on. A gap analysis is the comparison of a company's practices against a specified framework and identifies any “gaps” between the two. These types of analysis are almost always done by external parties or third parties to ensure that they are performed objectively without potential bias. Some industry compliance standards (such as HIPAA or PCI) may require an outside entity to perform such an analysis. The reasoning is that an outside consultant can often catch gaps that would not be obvious to personnel working in the area every day.

If a gap analysis is being performed against a business function, the first step is to identify a relevant industry-standard framework to compare business activities against. In information security, this usually means comparison against a standard such as ISO/IEC 27002 (best-practice recommendations for information security management). Another common comparison framework used as a cybersecurity benchmark is the NIST cybersecurity framework.

A gap analysis can be conducted against almost any business function, from strategy and staffing to information security. The common steps generally consist of the following:

- Establishing the need for the analysis and gaining management support for the efforts.

- Defining scope, objectives, and relevant frameworks.

- Identifying the current state of the department or area (which involves the evaluation of the department to understand current state, generally involving research and interviews of employees).

- Reviewing evidence and supporting documentation, including the verification of statements and data.

- Identifying the “gaps” between the framework and reality. This highlights the risks to the organization.

- Preparing a report detailing the findings and getting sign-off from the appropriate company leaders.

Since a gap analysis provides measurable deficiencies and, in some cases, needs to be signed off by senior leadership, it can be a powerful tool for an organization to identify weaknesses in their efforts for compliance.

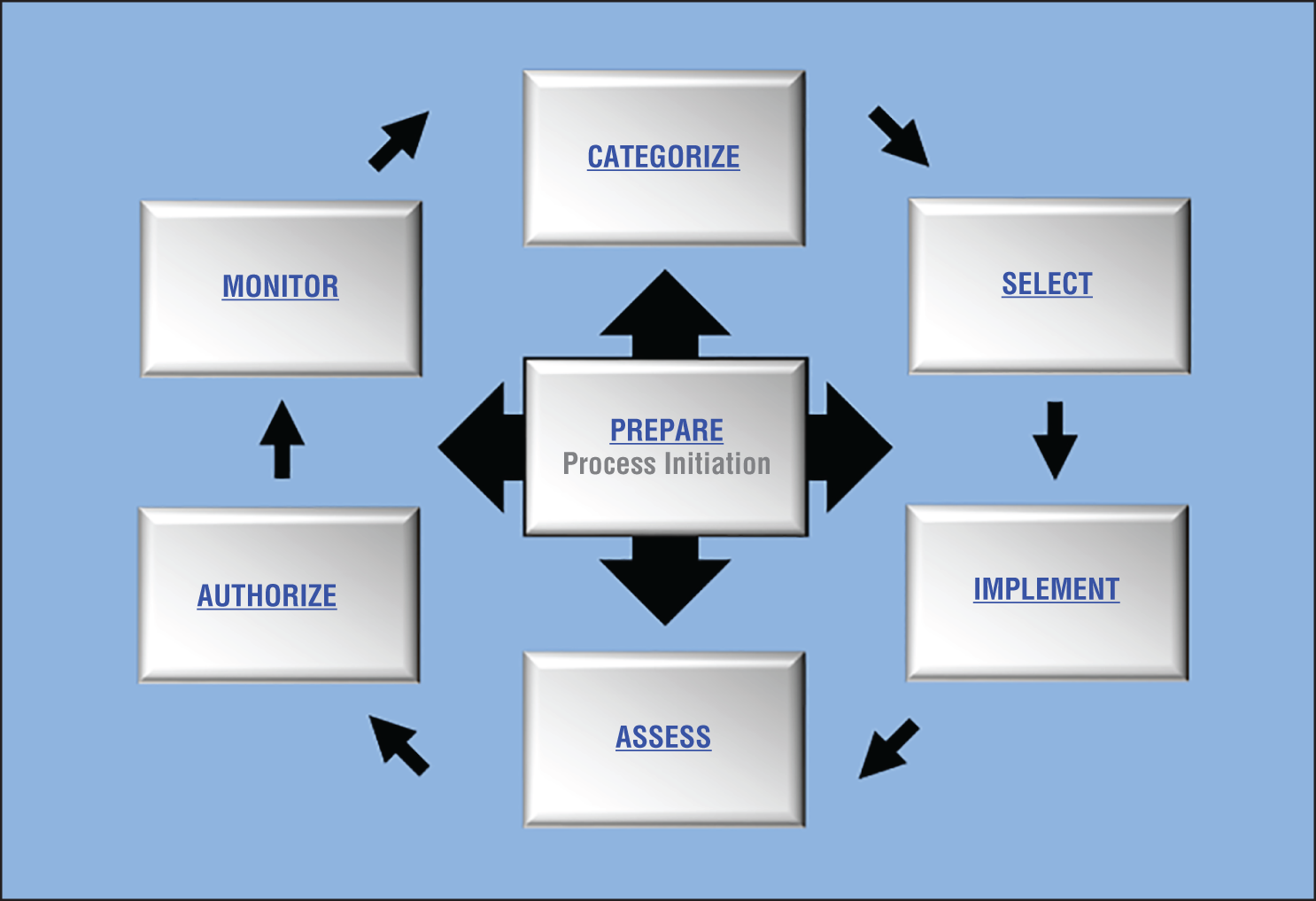

Audit Planning

Any audit, whether related to financial reporting, compliance, or cloud computing, must be carefully planned and organized to ensure that the results of the audit are relevant to the objectives. Audits genevrally consist of four phases, outlined in Figure 6.1.

FIGURE 6.1 Four phases of an audit

The four phases of an audit consist of the following:

- Audit planning

- Documentation and definition of audit objectives. This process is a collaborative effort to define what standards are being measured.

- Addressing concerns and risks.

- Defining audit output formats.

- Identifying auditors and qualifications.

- Identifying scope and restrictions.

- Audit fieldwork

- Conducting general controls walk-throughs and risk assessments.

- Interviewing key staff on procedures.

- Conducting audit test work, which may include physical and architectural assessments with software tools.

- Ensuring criteria are consistent with SLA and contracts.

- Audit reporting

- Conducting meetings with management to discuss findings.

- Discussing recommendations for improvement.

- Allowing for departmental response to findings.

- Audit follow-up

- Additional inquiry or testing could be performed to ensure compliance to recommendations.

- Identify lessons learned in the audit process.

In many organizations, audit is a continuous process. This is often structured into business activities to provide an ongoing view into how an organization is meeting compliance and regulatory goals. As a cloud security professional, audit is a powerful tool to ensure that your organization is not in the news for the wrong reasons.

Internal Information Security Management Systems

An information security management system (ISMS) is a systematic approach to information security consisting of processes, technology, and people designed to help protect and manage an organization's information. These systems are designed to strengthen the three aspects of the CIA triad: confidentiality, availability, and integrity. An ISMS is a powerful risk management tool in place at most medium and large organizations, and having one gives stakeholders additional confidence in the security measures in place at the company.