IN CONTEXT

Radical environmentalism

Deep ecology

1949 Aldo Leopold’s “Land Ethic” essay, calling for a new ethic in conservation, is posthumously published.

1962 Rachel Carson writes Silent Spring, a key factor in the birth of the environmental movement.

1992 The first Earth Summit is held in Rio, Brazil, signaling an acknowledgment of environmental issues on a global scale.

1998 The “Red/Green” coalition takes power in Germany, the first time an environmental party is elected to national government.

In recent decades, the economic, social, and political challenges of climate change have provided an imperative for the development of new political ideas. Environmentalism as a political project began in earnest in the 1960s, and has now entered the mainstream of political life. As a field of inquiry, the green movement has developed a variety of offshoots and avenues of thought.

The first environmentalists

Environmentalism has well-established roots. In the 19th century, thinkers such as the English critics John Ruskin and William Morris were concerned with the growth of industrialization and its subsequent impact on the natural world. But it was not until after World War I that a scientific understanding of the extent of the damage humans were causing to the environment began to develop. In 1962, American marine biologist Rachel Carson published her book Silent Spring, an account of the environmental problems caused by the use of industrial pesticides. Carson’s work suggested that the unregulated use of pesticides such as DDT had a dramatic effect on the natural world. Carson also included an account of the effects of pesticides on humans, placing mankind within the ecosystem rather than thinking of man as separate from nature.

"Earth does not belong to humans."

Arne Naess

Carson’s book provided the catalyst for the emergence of the environmental movement in mainstream politics. Arne Naess, a Norwegian philosopher and ecologist, credited Silent Spring with providing the inspiration for his work, which focused on the philosophical underpinnings for environmentalism. Naess was a philosopher of some renown at the University of Oslo, and was primarily known for his work on language. From the 1970s on, however, he embarked on a period of sustained work on environmental and ecological issues, having resigned from his position at the university in 1969, and devoted himself to this new avenue of thought. Naess became a practical philosopher of environmental ethics, developing new responses to the ecological problems that were being identified. In particular, he proposed new ways of conceiving the position of human beings in relation to nature.

Fundamental to Naess’s thought was the notion that the Earth is not simply a resource to be used by humans. Humans should consider themselves as part of a complex, interdependent system rather than consumers of natural goods, and should develop compassion for nonhumans. To fail to understand this point was to risk destroying the natural world through narrow-minded, selfish ambition.

Early in his career as an environmentalist, Naess outlined his vision of a framework for ecological thought that would provide solutions to society’s problems. He called this framework “Ecosophy T,” the T representing Tvergastein, Naess’s mountain home. Ecosophy T was based on the idea that people should accept that all living things—whether human, animal, or vegetable—have an equal right to life. By understanding oneself as part of an interconnected whole, the implications of any action on the environment become apparent. Where the consequences of human activity are unknown, inaction is the only ethical option.

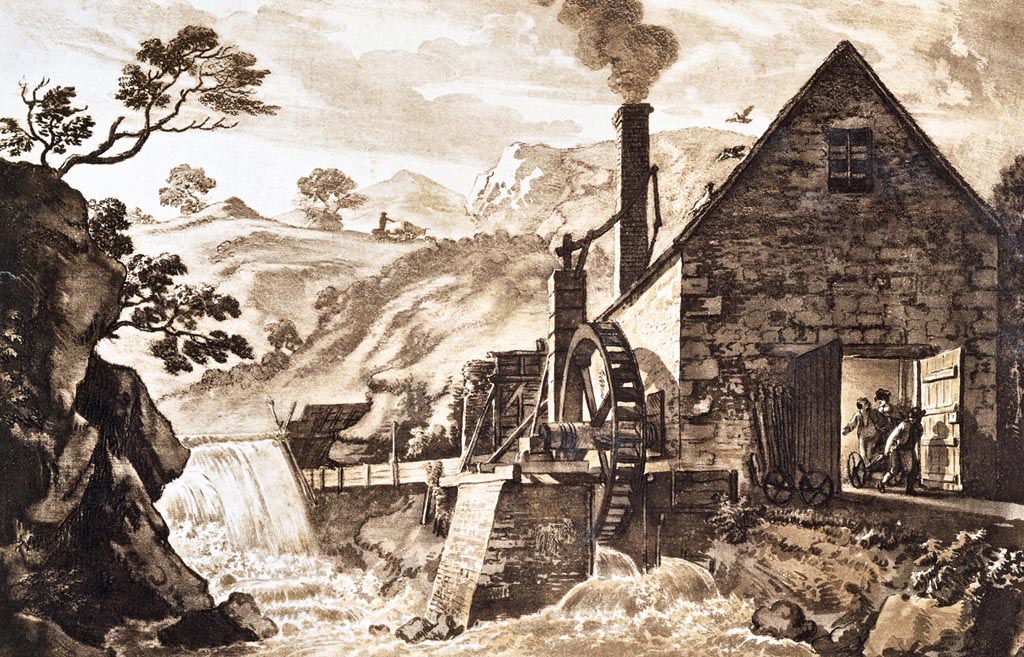

The Industrial Revolution changed people’s thinking about the environment. It was seen as a resource to be exploited, an attitude that Naess thought could lead to the destruction of mankind.

Deep ecology

Later in his career, Naess developed the contrasting notions of “shallow” and “deep” ecology to expose the inadequacies of much existing thinking on the subject. For Naess, shallow ecology was the belief that environmental problems could be solved by capitalism, industry, and human-led intervention. This line of thinking holds that the structures of society provide a suitable starting point for the solution of environmental problems, and imagines environmental issues in a human-centric way. Shallow ecology was not without value, but Naess believed it had a tendency to focus on superficial solutions to environmental problems. This view of ecology, for Naess, imagined mankind as a superior being within the ecosystem and did not acknowledge the need for wider social reform. The broader social, philosophical, and political roots of these problems were left unsolved—the primary concern was with the narrow interests of humans, rather than nature in its entirety.

"The supporters of shallow ecology think that reforming human relations towards nature can be done within the existing structure of society."

Arne Naess

In contrast, deep ecology says that, without dramatic reform of human behavior, irreparable environmental damage will be brought upon the planet. The fast pace of human progress and social change has tilted the delicate balance of nature, with the result that not only is the natural world being damaged, but mankind—as part of the environment—is ushering itself towards destruction. Naess proposes that, in order to understand that nature has an intrinsic value quite separate from human beings, a spiritual realization must take place, requiring an understanding of the importance and connection of all life. Human beings must understand that they only inhabit, rather than own, the Earth, and that only resources that satisfy vital means must be used.

Direct action

Naess combined his engagement in environmental thought with a commitment to direct action. He once chained himself to rocks near the Mardalsfossen, a waterfall in a Norwegian fjord, in a successful protest against the proposed site of a dam. For Naess, the realization that accompanied a deep ecological viewpoint must be used to promote a more ethical and responsible approach to nature. He was in favor of reducing consumerism and the standards of material living in developed countries as part of a broad-reaching program of reform. However, Naess disagreed with fundamentalist approaches to environmentalism, believing that humans could use some of the resources provided by nature in order to maintain a stable society.

Resolving environmental issues within current political, economic, and social systems is doomed to failure, according to Naess. What is needed is a new way of looking at the world around us, seeing mankind as a part of the ecological system.

Naess’s influence

Despite his preference for gradual change and his disdain for fundamentalism, Naess’s ideas have been adopted by activists with more radical perspectives. Earth First!, an international environmental advocacy group that engages in direct action, has adapted Naess’s ideas to support their own understanding of deep ecology. In their version of the philosophy, deep ecology can be used to justify political action that includes civil disobedience and sabotage.

As awareness of environmental issues grows, Naess’s ideas are gaining ever-greater resonance at a political level. Environmental issues show no respect for the boundaries of national governments, and generate a complex set of questions for theorists and practitioners alike. The green movement has entered the political mainstream, both through formal political parties and advocacy groups such as Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth. Naess’s work has an important place in providing a philosophical underpinning to these developments. His ideas have attracted controversy, and criticism has come from many quarters, including the accusation that they are disconnected from the reality of socioeconomic factors and given to a certain mysticism. Despite these criticisms, the political questions raised by the environmental movement, and the place of deep ecological perspectives within them, remain significant and seem sure to grow in importance in the future.

ARNE NAESS

Arne Naess was born near Oslo, Norway, in 1912. After training in philosophy, he became the youngest ever professor of philosophy at the University of Oslo at the age of 27. He maintained a significant academic career, working particularly in the areas of language and semantics. In 1969, he resigned from his position to devote himself to the study of ethical ecology, and the promotion of practical responses to environmental problems. Retreating to write in near solitude, he produced nearly 400 articles and numerous books.

Outside of his work, Naess was passionate about mountaineering. By the age of 19, he had built a considerable reputation as a climber, and he lived for a number of years in a remote mountain cabin in rural Norway, where he wrote most of his later work.

Key works

1973 The Shallow and the Deep, Long-Range Ecology Movement: A Summary

1989 Ecology, Community and Lifestyle: Outline of an Ecosophy

See also: John Locke • Henry David Thoreau • Karl Marx