IN CONTEXT

Anti-colonialism

Decolonization

1813 Simón Bolívar is called “The Liberator” when Caracas in Venezuela is taken from the Spanish.

1947 Gandhi’s nonviolent protests eventually achieve independence for India from British rule.

1954 The Algerian War of Independence against French colonial rule begins.

1964 At a meeting of the UN, Che Guevara argues that Latin America has yet to obtain true independence.

1965 Malcolm X speaks of obtaining rights for black people “by any means necessary.”

By the middle of the 20th century, European colonialism was in fast decline. Exhausted by two world wars and challenged by the social changes that accompanied industrialization, the grip of many colonial powers on their territories had loosened.

Grassroots movements demanding independence emerged with growing speed in the post-war era. The UK’s hold over Kenya was shaken by the growth of the Kenyan African National Union, while India secured independence in 1947 after a long struggle. In South Africa, the fight against colonial rule was entrenched in the far longer battle against apartheid oppression. Yet questions began to emerge about exactly what form postcolonial nations should take, and how best to deal with the legacy of violence and repression left behind by years of colonial rule.

Postcolonial thinking

Frantz Fanon was a French-Algerian thinker whose work deals with the effects of colonialism, and the response of oppressed peoples to the end of European rule. Drawing on the earlier perspectives of Marx and Hegel, Fanon takes an idiosyncratic approach to the analysis of racism and colonialism. His writing is concerned as much with language and culture as with politics, and frequently explores the relations between these different areas of enquiry, showing how language and culture are shaped by racism and other prejudices. Perhaps the most influential theorist of decolonization—the process of emancipation from colonial oppression—Fanon has had a major impact on anti-imperialist thinking, and his work inspires activists and politicians to this day.

"What matters is not to know the world but to change it."

Frantz Fanon

Fanon examined the impact and legacy of colonialism. His view of colonialism was closely tied up with white domination, and linked with a strong egalitarianism, rejecting the human oppression and loss of dignity that colonial rule entails. In part, this reflects Fanon’s role as a participant in the fight against oppression. In his book A Dying Colonialism, he puts forward an eyewitness view of the Algerian struggle for independence from French colonial rule, detailing the course of the armed conflict and the way it led to the emergence of an independent nation. The strategy and ideology of the armed anticolonial struggle are presented in their entirety, and he carries out a detailed analysis of the tactics used by both sides.

The Algerian War raged from 1954–1962 as French colonial forces tried to quell the Algerian independence movement. Fanon became a passionate spokesman for the Algerian cause.

Framework of oppression

Fundamentally, however, Fanon’s contribution was theoretical rather than practical, exposing the structures of oppression at work within colonial systems. He examined the hierarchies of ethnicity that provided the backbone of colonial oppression, showing how they ensure not only a strictly ordered system of privilege, but also an expression of difference that is cultural as well as political. In Algeria—and in other countries, such as Haiti—a postcolonial political order was created with the explicit intention of avoiding this kind of domination.

"The settler keeps alive in the native an anger which he deprives of an outlet; the native is trapped in the tight links of colonialism."

Frantz Fanon

Fanon’s vision of decolonization has an ambivalent relationship with violence. Famously, his work The Wretched of the Earth is introduced by Jean-Paul Sartre in a preface that emphasizes the position of violence in the struggle against colonialism. Sartre presents the piece as a call to arms, suggesting that the “mad impulse to murder” is an expression of the “collective unconsciousness” of the oppressed, brought about as a direct response to years of tyranny. As a result of this, it would be easy to read Fanon’s work as a clarion call to armed revolution.

The Mau Mau uprising against colonial rule in Kenya was violently suppressed by British forces, causing divisions among the majority Kikuyu, some of whom fought for the British.

Colonial racism

However, concentrating on the revolutionary aspect of Fanon’s work does a disservice to the complexity of his thought. For him, the violence of colonialism lay on the part of the oppressors. Colonialism was indeed violence in its natural state, but a violence that manifested itself in a number of different ways. It might be expressed in brute force, but also within the stereotypes and social divisions associated with the racist worldview that Fanon identified as defining colonial life. The dominance of white culture under colonial rule meant that any forms of identity other than those of white Europeans were viewed negatively. Divisions existed between colonizers and the people they ruled on the basis of the presumed inferiority of their culture.

Fanon believed that violence was part and parcel of colonial rule, and his work is a damning indictment of the violence meted out by colonial powers. He argues that the legitimacy of colonial oppression is supported only by military might, and this violence—as its solitary foundation—is focused on the colonized as a means of ensuring their acquiescence. Oppressed peoples face a stark choice between accepting a life of subjugation and confronting such persecution. Any response to colonialism needed to be developed in opposition to the assumptions of colonial rule, but also independently of it, in order to shape new identities and values that were not defined by Europe. Armed struggle and violent revolution might be necessary, but it would be doomed to failure unless a genuine decolonization could take place.

Toward decolonization

The Wretched of the Earth remains Fanon’s most significant publication, and provides a theoretical framework for the emergence of individuals and nations from the indignity of colonial rule. Exploring in depth the assumptions of cultural superiority identified elsewhere in his work, Fanon develops an understanding of white cultural oppression through a forensic analysis of the way it functioned: forcing the white minority’s values onto the whole of society. Nevertheless, he prescribes an inclusive approach to the difficult process of decolonization. Fanon’s ideas are based on the dignity and value of all people, irrespective of their race or background. He stresses that all races and classes can potentially be involved in—and benefit from—decolonization. Moreover, for Fanon, any attempt at reform based on negotiations between a privileged elite leading the decolonization process and colonial rulers would simply reproduce the injustices of the previous regime. Such an attempt would be rooted in assumptions of privilege and, more significantly, would fail, because there is a tendency of oppressed peoples to mimic the behavior and attitudes of the ruling elites. This phenomenon is particularly prevalent in the middle and upper classes, who are able—through their education and relative wealth—to present themselves as culturally similar to the colonialists.

"I am not the slave of the slavery that dehumanized my ancestors."

Frantz Fanon

By contrast, a genuine transition from colonialism would involve the masses, and represent a sustained move towards the creation of a national identity. A successful decolonization movement would develop a national consciousness, generating new approaches to art and literature in order to articulate a culture that was simultaneously in resistance to, and separate from, the tyranny of colonial power.

Fanon’s influence

These ideas about the violence of colonialism, and the importance of identity in shaping the future political and social direction of a nation, have had a direct impact on the way activists and revolutionary leaders treat the struggle against colonial power—The Wretched of the Earth is, in essence, a blueprint for armed revolution. Beyond this, Fanon’s role in shaping the understanding of colonialism’s workings and effects has left a lasting legacy. His insightful perspectives on the racist underpinnings of colonialism, and, in particular, his theories concerning the conditions for a successful decolonization, have been hugely influential in the study of poverty and the phenomenon of globalization.

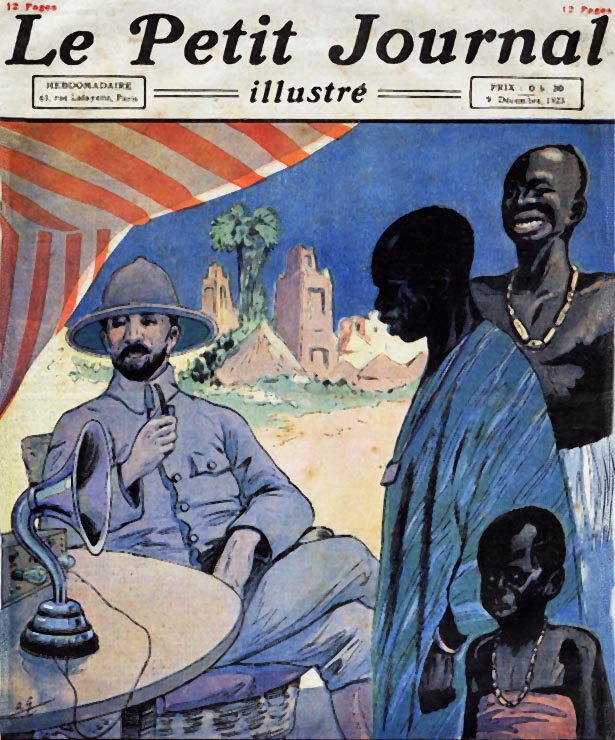

In France, colonizers were portrayed as civilized Europeans bringing order to savage natives. Such racist attitudes were used to justify the use of oppression and violence.

FRANTZ FANON

Frantz Fanon was born in Martinique in 1925 to a comfortably well-off family. After fighting for the Free French Army during World War II he studied medicine and psychiatry in Lyon. Here, he encountered the racist attitudes that were to inspire much of his early work.

On completing his studies, he moved to Algeria to work as a psychiatrist, and became a leading activist and spokesman for the revolution. He trained nurses for the National Liberation Front, and published his accounts of the revolution in sympathetic journals. Fanon worked to support the rebels until he was expelled from the country. He was appointed ambassador to Ghana by the provisional government toward the end of the struggle, but fell ill soon afterward. Fanon died of leukemia in 1961 at the age of just 35, managing to complete The Wretched of the Earth shortly before his death.

Key works

1952 Black Skin, White Masks

1959 A Dying Colonialism

1961 The Wretched of the Earth

See also: Simón Bolívar • Mahatma Gandhi • Manabendra Nath Roy • Jomo Kenyatta • Nelson Mandela • Paulo Freire • Malcolm X