IN CONTEXT

Social justice

Civil disobedience

1876–1965 The Jim Crow laws are implemented, legalizing a series of discriminatory practices in the southern states of the US.

1954 Brown versus Board of Education, a case adjudicated by the US Supreme Court, mandates the desegregation of public schools on the grounds that segregation is unconstitutional.

1964–68 In the US, a series of laws are passed banning discriminatory practices and restoring voting rights.

1973 US ground forces are withdrawn from Vietnam, amid waves of antiwar protest on the home front.

By the 1960s, the battle for civil rights in the United States was reaching its final stages. Since the reconstruction following the Civil War a century earlier, the Southern states of the US had been pursuing a policy of disenfranchisement and segregation of black Americans, through overt, legal means. This was codified in the so-called “Jim Crow” laws—a set of local and regional statutes that effectively stripped the black population of many basic rights. The struggle to win civil rights for black people had been ongoing since the end of the Civil War, but in the mid-1950s, it had developed into a broad movement based on mass protest and civil disobedience.

Struggle against ignorance

At the forefront of the movement was Dr. Martin Luther King, a civil rights activist who worked with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Inspired by the success of civil rights leaders elsewhere, and in particular by the nonviolent protests against British rule in India led by Mahatma Gandhi, King became perhaps the most significant figure to emerge from the struggle. In 1957, with other religious leaders, King had established the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), a coalition of black churches that broadened the reach of the organizations involved in the movement. For the first time, this had generated momentum on a national scale.

"Freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed."

Martin Luther King

Like many others in the civil rights movement, King characterized the struggle as one of enlightenment against ignorance. The long-standing beliefs of racial superiority and entitlement that dominated the government of the Southern states of the US had given rise to a political system that excluded black people and many other minorities. King felt that this position was fervently believed in by those in power, and that this “sincere ignorance” was at the root of the problems of inequality. Therefore, any attempt to deal with the problem solely through political means would be doomed to failure. Direct action would be needed to reform politics and win equality of participation and access in democratic life. At the same time, the movement for civil rights would also have to tackle the underlying attitudes of the majority toward minorities in order to achieve lasting change.

Nonviolent protest

In contrast to other leaders within the civil rights movement, such as Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael, King was committed to nonviolence as one of the fundamental principles of the struggle for equality. The utmost moral strength was required to adhere to nonviolence in the face of extreme provocation, but Gandhi had shown what was possible. Gandhi believed that the moral purpose of the protesters would be eroded, and public sympathy lost, if resistance became violent. As a result, King took great pains to ensure that his involvement in the civil rights movement did not promote violence, going so far as to cancel speeches and protests when he felt that they might result in violent action on the part of the activists. At the same time, King pursued a fearless confrontation of intimidation and violence when it was visited on civil rights activists. He frequently led demonstrations from the front, was injured more than once, and was jailed on numerous occasions. Images of the brutality of the police toward civil rights activists became one of the most effective means of garnering nationwide support for the cause.

"Nonviolence means avoiding not only external physical violence but also internal violence of spirit. You not only refuse to shoot a man, but you refuse to hate him."

Martin Luther King

King’s adherence to nonviolence also inspired his opposition to the Vietnam War. In 1967, he delivered his celebrated “Beyond Vietnam” speech, which spoke out against the ethics of conflict in Vietnam, branding it as American adventurism, and taking issue with the resources lavished upon the military. In part, King felt that the war was morally corrupt since it consumed vast amounts of the federal budget, which could otherwise be spent on relieving the problems of poverty. Instead, as he saw it, the war was in fact compounding the suffering of poor people in Vietnam.

The difference of opinion between those advocating non-violence and those prepared to use violence in the struggle for civil rights is a major area of debate in the discussion of civil disobedience to this day. In his “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” King articulated his strategy for confronting the ignorance of racism in the US, stating that “nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community, which has constantly refused to negotiate, is forced to confront the issue.” However, critics within the movement felt that the pace of change was too slow, and that there was a moral imperative to respond to violence and intimidation in kind.

Nonviolent civil disobedience took many forms during the fight for civil rights, such as refusing to sit in the “colored” section at the back of public buses.

Against all inequality

King’s vision for the civil rights movement developed as the 1960s progressed, and he broadened his focus to include inequality more generally, proposing to tackle economic, as well as racial, injustice. In 1968, he began the “Poor People’s Campaign,” focusing on income, housing, and poverty, and demanding that the federal government invest heavily in dealing with the problems of poverty. Specifically, the campaign promoted a minimum income guarantee, an expansion in social housing, and a commitment on the part of the state to full employment. The campaign was intended from the outset to unite all racial groups, focusing on the common problems of poverty and hardship. However, King died before it began and, despite a widely publicized march and series of protests, the movement did not match the success of the campaigns for civil rights. The link between racism and poverty had long been a theme of the civil rights movement, and formed a part of much of the activism in which King was involved. The 1963 “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom” had the fight against racism at its core, but also demanded the extension of economic rights. King’s stand against the Vietnam War had explicitly criticized US involvement in the conflict as distracting attention and financial support from the battle against poverty. Beyond these specific campaigns, a commitment to an extension of social welfare was a consistent theme throughout much of the activism King had pursued with the SCLC.

"Discrimination is a hellhound that gnaws at Negroes in every waking moment of their lives to remind them that the lie of their inferiority is accepted as truth."

Martin Luther King

King believed that solving the problems of poverty meant tackling another facet of the ignorance he had identified in the fight for racial equality. In his final book, Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?, he argued for the need for change in attitudes toward poor people. Part of the problem of poverty, he felt, lay in stereotyping the poor as idle. He suggested that prevailing attitudes had meant that “economic status was considered the measure of the individual’s abilities and talents” and that “the absence of worldly goods indicated a want of industrious habits and moral fibre.” In order to tackle poverty, this underlying attitude needed to be challenged.

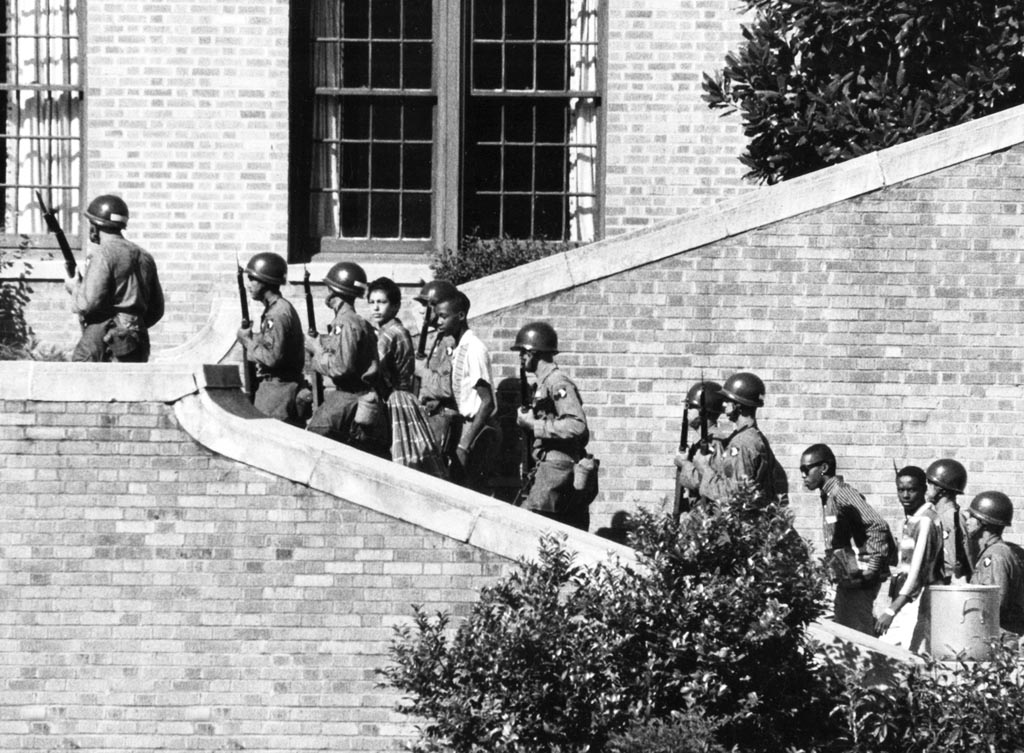

Nine black students challenged the segregation at Little Rock’s whites-only Central High School in 1957. They were refused entry, and federal troops were sent in to ensure their safety.

King’s legacy

King remains one of the most influential civil rights leaders of the modern era. His oratory is timeless and has passed into the modern vernacular, and his work has inspired the activists who followed him in the US and worldwide. Perhaps the most concrete measure of his influence, however, is in the reform of civil rights that occurred as a result of the movement he helped to lead. The Voting Rights Act introduced in 1965 and the Civil Rights Act of 1968 signaled the end of the Jim Crow laws, and removed overt discrimination from the Southern states. The last great injustice he tackled, however—the problem of poverty—remains unsolved.

"When an individual is protesting society’s refusal to acknowledge his dignity as a human being, his very act of protest confers dignity on him."

Bayard Rustin

King knew he was a target for assassination, but this did not stop him from leading the civil rights movement from the front. The Civil Rights Act was passed just days after his death.

MARTIN LUTHER KING

Born in Atlanta, Georgia, Martin Luther King, Jr. was educated at Boston University. By 1954, he had become a pastor and a senior figure within the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). In this capacity, he became a leader in the civil rights movement, organizing protests across the South, including the 1955 boycott of the Montgomery bus system. In 1963, he was arrested during a protest in Birmingham, Alabama, and jailed for more than two weeks.

On his release, King led the March on Washington and delivered his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964 and led the popular pressure for the repeal of the Jim Crow laws. King was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee, in March 1968, while on a visit in support of striking sanitation workers.

Key works

1963 Why We Can’t Wait

1963 Letter from Birmingham Jail

1967 Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?

See also: Henry David Thoreau • Mahatma Gandhi • Nelson Mandela • Frantz Fanon • Malcolm X