IN CONTEXT

Republicanism

The general will

1513 Niccolò Machiavelli’s The Prince offers a modern form of politics in which a ruler’s morality and the concerns of state are strictly separate.

1651 Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan argues for the foundation of the state on the basis of the social contract.

1789 The Jacobin Club begins meeting in Paris. Its extremist members attempt to apply Rousseau’s principles to revolutionary politics.

1791 In Britain, Edmund Burke blames Rousseau for the “excesses” of the French Revolution.

For centuries in Western Europe, a certain style of thinking about human affairs prevailed. Under the sway of the Catholic Church, the writings of ancient Greece and Rome had been steadily studied and rehabilitated, with outstanding intellectuals such as Augustine of Hippo and Thomas Aquinas rediscovering ancient thinkers. A scholastic approach, treating history and society as essentially unchanging and the higher purpose of morality as fixed by God, had come to dominate the ways in which society was considered. It took the upheavals associated with the development of capitalism and urban life to begin to tear this approach apart.

Rethinking the status quo

In the 16th century, Niccolò Machiavelli, in a radical departure with the past, had turned the scholastic tradition on its head in The Prince, drawing on ancient examples not to act as a guide to a moral life, but to demonstrate how an effective statecraft or politics could be cynically performed. Thomas Hobbes, writing his Leviathan during the English Civil War of the mid-17th century, used the scientific method of deduction, rather than the reading of ancient texts, to argue for the necessity of a strong state to preserve security among the people.

"You are undone if you once forget that the fruits of the Earth belong to us all, and the Earth itself to nobody."

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

However, it was Jean-Jacques Rousseau, an idiosyncratic Swiss exile from Geneva whose personal life scandalized polite society, who proposed the most radical break with the past. Rousseau’s autobiographical Confessions, published after his death, reveal that it was during his time in the Italian island-port of Venice—while working as an underpaid ambassadorial secretary—that he decided “everything depends entirely on politics.” People were not inherently evil, but could become so under evil governments. The virtues he saw in Geneva, and the vices in Venice—in particular, the sad decline of the city-state from its glorious past—could be traced not to human character, but to human institutions.

Society shaped by politics

In his Discourse on Inequality of 1754, Rousseau broke with previous political philosophy. The ancient Greeks and others writing on society—including Ibn Khaldun in the 14th century—viewed political processes as subject to their own laws, working with an unchanging human nature. The Greeks, in particular, had a cyclical view of political change in which good or virtuous modes of government—whether monarchy, democracy, or aristocracy—would degenerate into various forms of tyranny before the cycle was renewed again. Society, as such, did not change, merely its form of government.

Rousseau disagreed. If, as he argued, society could be shaped by its political institutions, there was—in theory—no limit to the ability of political action to reshape society for the better.

This assertion marked Rousseau as a distinctively modern thinker. Nobody before Rousseau had systematically thought of society as something distinct from its political institutions, as an entity that was itself capable of being studied and acted upon. Rousseau was the first, even among the philosophers of the Enlightenment, to reason in terms of social relations among people. This new theory begged an obvious question: If human society was open to political change, why, then was it so obviously imperfect?

The corruption Rousseau found in Venice exemplified for him the way in which bad government causes people to be bad. He contrasted this with the propriety of his home town, Geneva.

On property and inequality

Rousseau provided, again, an exceptional answer, and one that scandalized his fellow philosophers. As his starting point, he asked that we consider humans without society. Thomas Hobbes had argued such people would be savages, living lives that were “poor, nasty, brutish, and short,” but Rousseau asserted quite the opposite. Human beings free from society were well-disposed, happy creatures, content in their state of nature. Only two principles guided them: the first, a natural self-love and desire for self-preservation; the second, a compassion for their fellow human beings. The combination of the two ensured that humanity reproduced itself, generation after generation, in a state close to that of other animals. This happy condition was, however, brutally brought to a close by the creation of civil society and, in particular, the development of private property. The arrival of private property imposed an immediate inequality on humanity that did not previously exist— between those who possessed property, and those who did not. By instituting this inequality, private property provided the foundations of further divisions in society— between those of master and slave, and then in the separation of families. On the foundation of these new divisions, private property then provided the mechanism by which a natural self-love turned into destructive love of self, now driven by jealousy and pride, and capable of turning against other human beings. It became possible to possess, and acquire, and to judge oneself against others on the basis of this material wealth. Civil society was the result of division and conflict working against a natural harmony.

"The mere impulse of appetite is slavery, while obedience to the law we prescribe to ourselves is liberty."

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

The advent of private property was responsible for all of the divisions and inequalities that exist within society, according to Rousseau.

The loss of liberty

Rousseau built on this argument in The Social Contract, published in 1762. “Man was born free, and he is everywhere in chains,” he wrote. While his earlier writings had been resolutely bleak in their opposition to conventional society, The Social Contract sought to provide the positive foundations for politics. Like Hobbes and Hugo Grotius before him, Rousseau saw the emergence of a sovereign power in society as the result of a social contract. People could choose to forfeit their own rights to a government, handing over their full liberty to a sovereign in return for the king—in Hobbes’s account—providing security and protection. Hobbes argued that life without a sovereign pushed humanity back to a vile state of nature. By handing over a degree of liberty—in particular, liberty to use force—and swearing obedience, a people could guarantee peace, since the sovereign could end disputes and enforce punishments.

Rousseau rejected this. It was impossible, he thought, for any person or persons to hand over their liberty without also handing over their humanity and therefore destroying morality. A sovereign could not hold absolute authority, since it was impossible for a free man to enslave himself. Establishing a ruler superior to the rest of society transformed humanity’s natural equality into a permanent, political inequality. For Rousseau, the social contract envisioned by Hobbes was a form of hoax by the rich against the poor—there was no other way that the poor would agree to a state of affairs in which the social contract preserved inequality.

The societies that existed, then, were not formed in the state of nature, deriving their legitimacy from improvement over that time. Rather, Rousseau argued, they were formed after we had left the state of nature, and property rights—with the resultant inequalities—had been established. Once property rights were in place, conflicts would ensue over the distribution of those rights. It was civil society and property that led to war, with the state as the agency through which war could be pursued.

Revising the social contract

What Rousseau offered in The Social Contract was the possibility of this dire situation transforming into its opposite. The state and civil society were burdens on individuals, depriving them of a natural freedom. But they could be changed into positive extensions of our freedom, if political institutions and society were organized effectively. The social contract, instead of being a pact written in fear of our evil natures, could be a contract written in the hope of improving ourselves. The state of nature might have been free, but it meant people had no greater ideals than that of their animal appetites. More sophisticated desires could only appear outside the state of nature, in civil society. To achieve this, a new kind of social contract would be written.

Where Hobbes saw law only as a restraint, and freedom existing only in the absence of law, Rousseau argued that laws could become an extension of our freedom, provided that those subject to the law also prescribed the law. Freedom could be won within the state, rather than against it. To achieve this, the whole people must become sovereign. A legitimate state is one that offers greater freedom than is obtainable in the raw state of nature. To secure that positive freedom, a people must also be equal. In Rousseau’s new world, liberty and equality march together, rather than in opposition.

Popular sovereignty

In The Social Contract, Rousseau laid down, in outline, many of the claims that would underlie the development of the left in politics over subsequent centuries: a belief that freedom and equality were partners, not enemies; a belief in the ability of law and the state to improve society; and a belief in the people as a sovereign entity, from which the state gained its legitimacy. Despite the vehemence of his attack on private property, Rousseau was not a socialist. He believed that the total abolition of private property would pitch liberty and equality into conflict, while a moderately fair distribution of property could enhance freedom. Indeed, he later went on to argue for an agrarian republic of small-scale farmers. Nonetheless, Rousseau’s ideas were, for the time, dramatically radical. By investing the whole people with sovereignty, and by identifying sovereignty with equality, he offered a challenge to an entire existing tradition of Western political thought.

Rousseau was not against property, as long as it was distributed fairly. He considered a small, agrarian republic in which all citizens were farmers to be an ideal form of state.

A new contract

Rousseau did not equate this idea of popular sovereignty with democracy as such, fearing that a directly democratic government, requiring all citizens to participate, was uniquely prone to corruption and civil war. Instead, he envisioned sovereignty being invested in popular assemblies capable of delegating the tasks of government—via a new social contract, or a constitution—to an executive. The sovereign people would embody the “general will,” an expression of popular assent. Day-to-day government, however, would depend on specific decisions, requiring a “particular will.”

It was in this very distinction, Rousseau thought, that conflict between the “general will” and the “particular will” opened up, paving the way for the corruption of the sovereign people. It was this corruption that so marked the world of Rousseau’s time, in his view. Instead of acting as a collective, sovereign body, the people were consumed by the pursuit of private interests. In place of the freedom of popular sovereignty, society had pushed people into separate, private spheres of endeavor, whether in the arts, science, or literature, or in the division of labor. This numbed people into habitual deference, and instilled a spirit of passivity.

To ensure the government was an authentic expression of the popular, general will, Rousseau believed that participation in its assemblies and procedures should be compulsory, removing—as far as possible—the temptations of the private will. But this belief in the necessity of combating private desires is exactly where Rousseau’s later, liberal critics have found the deepest fault.

Private versus general will

The “general will,” however desirable in theory, could easily be vested in deeply oppressive arrangements. Not least was the difficulty in actually ascertaining the “general will.” The road for an individual or a group claiming to express the general will, when merely exercising their own particular wills, was clearly wide open. Rousseau, in desiring to make the people sovereign, could be presented as the forefather of totalitarianism. What repressive regime since his time has not attempted to claim the support of “the people”?

Indeed, Rousseau’s provisions against factions and divisions among the people—which he, like Machiavelli, saw as undermining the state—could certainly turn into a tyranny of the majority, in which unpopular minorities suffer at the hands of those exercising the “general will.” Rousseau’s recommendation for dealing with this dilemma was to recognize the inevitability of factions, and to multiply them indefinitely—making so many particular wills that no one of them would stand a chance of representing the general will, nor would any one faction be dominant enough to oppose the general will.

States formed under illegitimate social contracts based on the fraud of the powerful were not capable of expressing this will, precisely because their subjects were bound to them only by deference to authority, not by mutual assent. However, if the apparent contracts between rulers and ruled were illegitimate, based on a denial of people’s sovereignty rather than its expression, it would follow that the people had every right to depose their rulers. That, at least, is how the more radical of Rousseau’s later followers came to interpret him. Rousseau himself was at best ambiguous on the issue of outright revolt, frequently denouncing violence and civil unrest and urging respect for existing laws.

The French Revolution began when an angry mob stormed the Bastille in Paris on July 14, 1789. The medieval fortress and prison was a symbol of royal power.

A revolutionary icon

Rousseau’s belief in the sovereignty of the people, and the perfectibility of both people and society, has had an immense impact. In the French Revolution, the Jacobins adopted him as a figurehead for their own belief in the necessity of a ruthlessly complete, egalitarian transformation of French society. In 1794, he was reinterred in the Panthéon, Paris, as a national hero. Over the next two centuries, Rousseau’s work also acted as a touchstone for all those who wished to see society radically overhauled for the common good, from Karl Marx onward.

"We are approaching a state of crisis and the age of revolutions."

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Similarly, the arguments against Rousseau, during his life and after, have helped to shape both conservative and liberal thought. In 1791, Edmund Burke, one of the founders of modern conservatism, held Rousseau to be almost personally responsible for the French Revolution and what he saw as its excesses. Writing almost 200 years later, the radical-liberal philosopher Hannah Arendt believed the errors in Rousseau’s thinking helped to drive the Revolution away from its liberal roots.

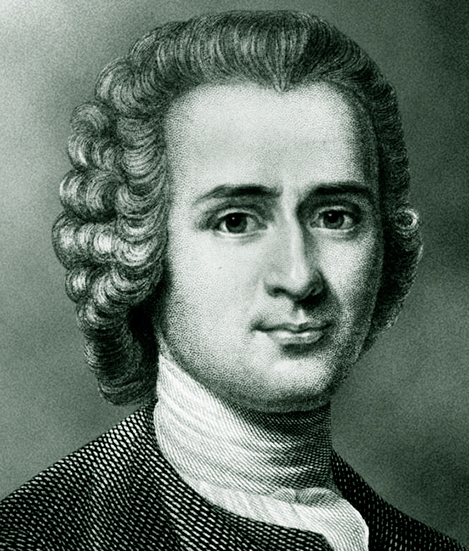

JEAN-JACQUES ROUSSEAU

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was born in Geneva, Switzerland. The son of a freeman entitled to vote in city elections, he never wavered in his appreciation of Geneva’s liberal institutions. Inheriting a large library and a voracious appetite for reading, Rousseau received no formal education. At the age of 15, an introduction to the noblewoman Françoise-Louise de Warens led to his conversion to Catholicism, exile from Geneva, and disownment by his father.

Rousseau began studying in earnest in his 20s and was appointed secretary to the ambassador to Venice in 1743. He left soon after for Paris, where he built a reputation as a controversial essayist. When his books were banned in France and Geneva, he fled briefly to London, but soon returned to France where he spent the rest of his life.

Key works

1754 Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men

1762 Emile

1762 The Social Contract

1770 Confessions

See also: Ibn Khaldun • Niccolò Machiavelli • Hugo Grotius • Thomas Hobbes • Edmund Burke • Hannah Arendt