IN CONTEXT

Utilitarianism

Public policy

1748 Montesquieu asserts in The Spirit of the Laws that liberty in England is maintained by the balance between the power of different parts of society.

1748 David Hume suggests that good and bad can be seen in terms of usefulness.

1762 Jean-Jacques Rousseau argues in The Social Contract that every law the people have not ratified in person is not a law.

1861 John Stuart Mill warns of the “tyranny of the majority,” and states that government should only interfere with individual liberties if they cause harm to others.

The idea that government has but a choice of evils runs right through the work of English philosopher Jeremy Bentham, from as early as 1769, when he was a young trainee lawyer, to the end of his life 50 years later, when he had become a hugely influential figure in British and European political thought.

The year 1769, Bentham wrote half a century later, was “a most interesting year.” At the time, he was reading the works of philosophers such as Montesquieu, Beccaria, and Voltaire—all forward-thinking leaders of the continental Enlightenment. But it was the work of two British writers—David Hume and Joseph Priestley—that set off great sparks of revelation in young Bentham’s mind.

Morality and happiness

In An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding (1748), Hume says that one way to distinguish good and bad is by usefulness. A good quality is only really good if it is put to good use. But for the sharp, no-nonsense lawyer Bentham, this was still too vague. What if you consider usefulness, or “utility,” to be the only moral quality? What if you decide whether an action is good or not entirely by its usefulness, by whether it produces a good effect—crucially, whether it makes people happier or not?

Looked at in this way, all morality is at root about creating happiness and avoiding misery. Any other description is an unnecessary elaboration or, worse, a deliberate veiling of the truth. Religions are often guilty of this obfuscation, Bentham says, but so too are those high-flown political idealists who assert people’s rights and so miss the point that it is all really about making people happy.

This is true, Bentham argues, not just on a personal and moral level, but on a public and political level, too. And if both private morality and public policy are reduced to this simple aim, everyone can agree—and men and women of good will can work together to achieve the same end.

So what, then, is a happy, useful outcome? Bentham is a realist and accepts that even the best action produces some bad along with the good. If one child has two sweets, another has one, and a third has none, the fairest action for the children’s parents would be to take a sweet from the child with two and give it to the one with none. This still leads to one of the children losing a sweet. Similarly, any government action will work to the advantage of some but the disadvantage of others. For Bentham, such actions should be judged according to the following criterion: an action is good if it produces more pleasure than pain.

The greatest good

Reading Priestley’s An Essay on the First Principles of Government (1768) sparked off the second great revelation of 1769 for Bentham. He draws from Priestley the idea that a good act is one that produces the greatest happiness for the greatest number. In other words, it’s all about arithmetic. Politics can be simplified to one question—does it make more people happy than it makes sad? Bentham developed a mathematical method, which he called “felicific calculus,” to work out whether a given government act produced more happiness or less.

This is where the idea that “government has but a choice of evils” comes in. Any law is a restriction on human liberty, argues Bentham—an interference with the individual’s freedom to act completely as he or she wants. Therefore, every law is necessarily an evil. But doing nothing may also be an evil. The decision rests on the arithmetic. A new law can be justified if, and only if, it does more good than harm. He likens government to a doctor who should only intervene if he is sure the treatment will do more good than harm—an apt analogy for Bentham’s time, when doctors frequently made patients more ill by bleeding them, draining some of their blood in an attempt to clear out disease. When deciding the punishment for a criminal, for instance, the lawmaker must take into account not just the direct effects of the mischief, but the secondary effects, too—a robbery does not just harm the victim, but creates alarm in the community. The punishment must also make the robber worse off, so that it outweighs any profit he gained by committing the crime.

For Bentham, each and every human should count as one unit in the sum of human happiness, regardless of wealth or status.

Hands-off government

Bentham extended his idea into the field of economics, endorsing the view of Scottish economist Adam Smith, who argued that markets work best without government restrictions. Since Bentham’s time, many people have used his warning to lawmakers as a justification for “hands-off” government—for scaling back bureaucracy and for deregulation. His views have even been used as an argument in favor of a conservative government that avoids introducing new laws, especially new laws that try to change people’s behavior. However, Bentham’s arguments also have far more radical implications. Governments cannot stand still until everyone is infinitely happy, which will never happen. This means there is always work to do. Just as most people continue to search for happiness throughout their lives, governments must constantly strive to make ever more people happy.

"It is the greatest good to the greatest number of people which is the measure of right and wrong."

Jeremy Bentham

Bentham’s moral arithmetic highlights not just the benefits of happiness, but its cost. It makes it clear that for someone to be happy, someone else may have to pay a price. For a very rich few to live in comfort, for instance, many others must live in discomfort. Each person only counts as one unit in Bentham’s sum of human happiness. This means that this imbalance is immoral, and it is every government’s duty to continually work to redress the situation.

"Good is pleasure or exemption from pain… Evil is pain or loss of pleasure."

Jeremy Bentham

Inequalities in society mean that a rich minority exists alongside the poor. For Bentham this is morally unacceptable, and a government’s role is to ensure that a balance is reached.

Pragmatic democracy

So how can rulers be persuaded to spread the wealth, when that would seem to make them less happy? The answer, Bentham argues, is more democracy, meaning the extension of the franchise. If rulers fail to increase human happiness for the greatest number, they get voted out at the next election. In a democracy, politicians have a vested interest in increasing happiness for the majority to ensure they are reelected. While other thinkers, from Rousseau to Paine, were pushing for democracy as a natural right—without which a man is denied his humanity—Bentham argued for it entirely pragmatically: as a means to an end. The idea of natural laws and rights is, to Bentham, nothing more than “nonsense on stilts.”

With their costs and benefits, profit and loss, Bentham’s arguments for extending voting rights appealed to hard-nosed British industrialists and businessmen—the rising new power base in the Industrial Revolution—in a way that no amount of idealism and talk of man’s natural rights could. Bentham’s down-to-earth, “utilitarian” arguments helped to shift Britain toward parliamentary reform and liberalism in the 1830s. Today, a Benthamite approach is a useful everyday benchmark for public policy decisions, encouraging governments to consider whether each policy is, on balance, good for the majority of people.

Bentham’s ideas were satirized by Charles Dickens, whose character Mr. Gradgrind, in the novel Hard Times, runs a school based on cold, hard facts, leaving little room for fun.

Hard facts

However, there are some real problems with Bentham’s ideal-free recipe of utilitarianism. The English author Charles Dickens hated the new breed of utilitarians that followed Bentham, and satirized them mercilessly in his novel Hard Times (1854), depicting them as killjoys stamping on the imagination and sapping the human spirit with their insistence on reducing life to hard facts. It is not a picture that Bentham, a deeply empathetic man, would necessarily recognize, but it was a clear reference to his reduction of every issue to arithmetic. One recurring criticism of Bentham’s idea is that it encourages scapegoating. The greatest happiness principle can permit huge injustices if the overall effect is general happiness. After a terrible terrorist bombing, for instance, the police are under great pressure to find the perpetrators. The general population will be much happier and the alarm will subside if the police arrest anyone who appears to fit the bill, even if they are not actually the guilty party (provided there are no further attacks).

Following Bentham’s argument, some critics claim, it is morally acceptable to punish the innocent if their suffering is outweighed by an increase in the happiness of the general population. Supporters of Bentham can get around this problem by saying that the general population would be unhappy to live in a society in which innocent people are made into scapegoats. But that issue only arises if the population finds out the truth; if the targeting of scapegoats is kept secret, it would appear justified according to Bentham’s logic.

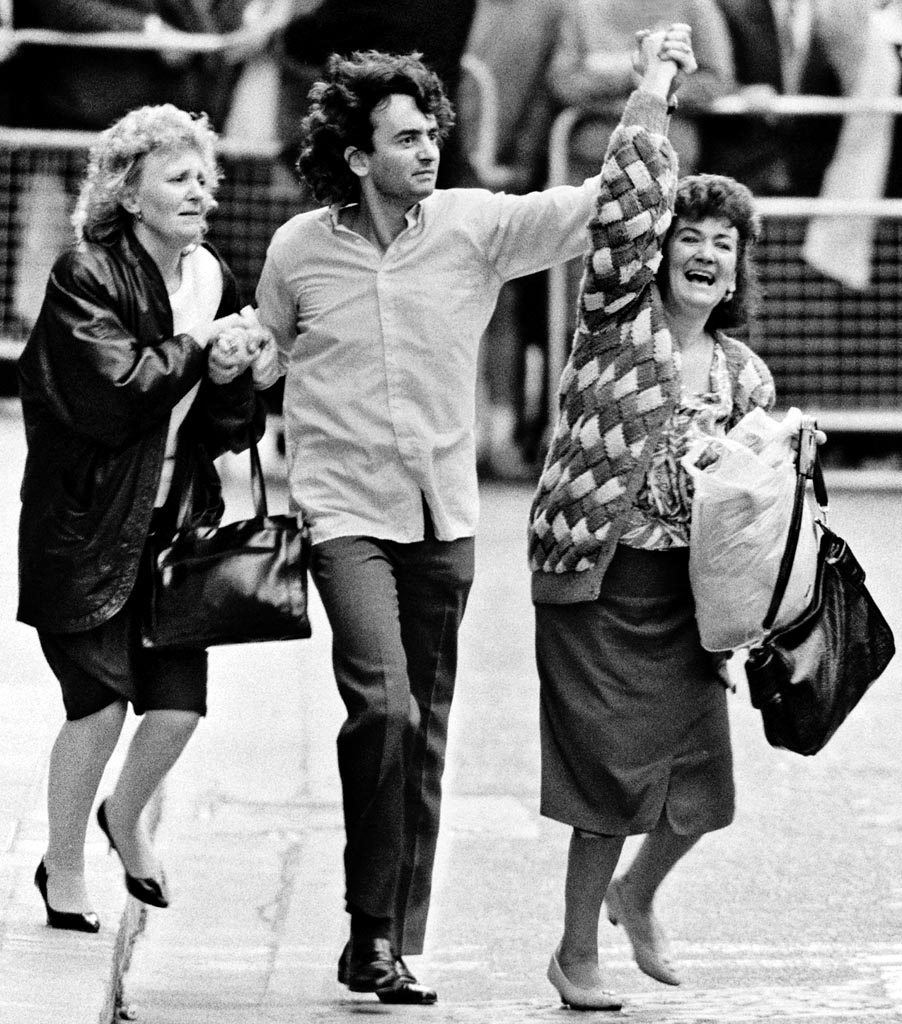

Utilitarian arguments have been used to justify the prosecution of innocent people—such as Gerry Conlon, accused of IRA bombings—on the basis that the majority is made happier.

JEREMY BENTHAM

Jeremy Bentham was born in Houndsditch, London, in 1748, to a family who were financially comfortable. He was expected to become a lawyer, and he went to Oxford University aged just 12, graduating to train as a barrister in London at 15. But the chicanery of the legal profession depressed him, and he became more interested in legal science and philosophy. Bentham retired to London’s Westminster to write, and for the next 40 years, he turned out works of commentary and ideas on legal and moral matters. He began by criticizing the leading legal authority William Blackstone for his assumption that there was nothing essentially wrong with Britain’s laws, then he went on to develop a complete theory of morals and policy. This was the basis of the utilitarian ethic that had already come to dominate British political life by the time of his death in 1832.

Key works

1776 Fragment on Government

1780 Introduction to Principles of Morals and Legislation

1787 Panopticon

See also: Jean-Jacques Rousseau • Immanuel Kant • John Stuart Mill • Friedrich Hayek • John Rawls