IN CONTEXT

Federalism

Armed citizenry

44–43 BCE Cicero argues in his Philippics that people must be able to defend themselves, just as wild beasts do in nature.

1651 Thomas Hobbes argues in Leviathan that by nature, men have a right to defend themselves forcefully.

1968 After the assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, federal restrictions on gun ownership are introduced.

2008 The Supreme Court decides that the Second Amendment protects an individual’s right to keep a gun at home for self-defense.

Even as the Founding Fathers were putting the finishing touches on the US Constitution in 1788, demands came for the addition of a Bill of Rights. The idea that the people have a right to keep and bear arms appears as the Second Amendment in this bill with the words, “the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” The exact wording is crucial, since it has become the focus of modern debate over gun control, and how much freedom US citizens have by law to own and carry guns.

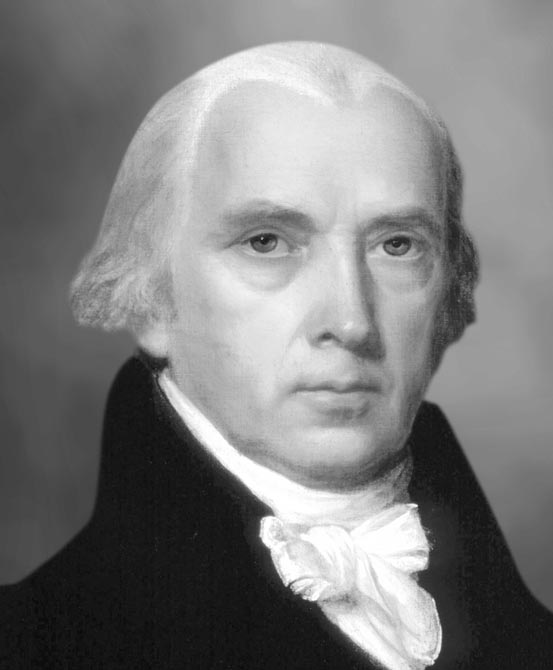

The architect of the Bill of Rights was Virginia-born James Madison, who was also one of the main creators of the Constitution itself. This makes him possibly unique among political thinkers in that he was able to put his ideas directly into practice—ideas that are still, two centuries later, the basis of the political way of life of the world’s most powerful nation. Indeed, in later becoming president, Madison climbed to the very peak of the political edifice that he had himself created.

The Bill of Rights is considered by some as the very embodiment of the Enlightenment thinking on natural rights, which began with John Locke and culminated in Thomas Paine’s inspirational call for the Rights of Man. Though the latter stressed the importance of democracy (the universal right to vote) as a principle in his treatise, Madison’s intentions were more pragmatic. They were rooted in the tradition of English politics—where parliament sought to prevent the sovereign from overreaching his power, rather than striving to protect basic universal freedoms.

Defense from the majority

As he admitted in a letter to Thomas Jefferson, the only reason Madison put forward the Bill of Rights was to satisfy the demands of others. He personally believed that the establishment of the Constitution by itself, and so the creation of proper government, should have been enough to guarantee that fundamental rights are protected. Indeed, he admitted that the addition of a Bill of Rights implied that the Constitution was flawed, and could not protect these rights in itself. There was also a risk that defining specific rights would impair protection of rights that were not specified. Moreover, Madison acknowledged that bills of rights had not had a happy history in the United States.

But there were also strong reasons why a bill of rights might be a good idea. Like most of the Founding Fathers, Madison was nervous of the power of the majority. “A democracy,” wrote Thomas Jefferson, “is nothing more than mob rule, where fifty-one percent of the people may take away the rights of the other forty-nine.” A Bill of Rights might help protect the minority against the mass of the people.

“In our Governments,” Madison wrote, “the real power lies in the majority of the Community, and the invasion of private rights is chiefly to be apprehended, not from acts of Government contrary to the sense of its constituents, but from acts in which the Government is the mere instrument of the major number of the constituents.” In other words, the Bill of Rights was actually intended to protect property owners against the democratic instincts of the majority.

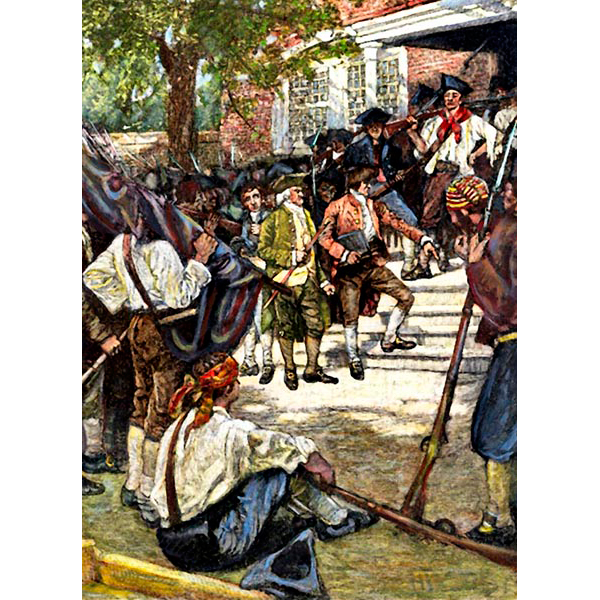

Shay’s Rebellion in 1786–87 saw a rebel militia seize Massachusetts’s courthouse. Quashed by government forces, it encouraged the principle of strong government in the Constitution.

Militias legitimized

Madison also had a simple political reason for creating the Bill of Rights. He knew he would not gain support for the Constitution from the delegates of some individual states if he did not. After all, the Revolutionary War had been fought to challenge the tyranny of centralized power, so these delegates were wary of a new central government. They would only ratify the Constitution if they had some guarantee of protection against it. So rights were not natural laws, but the states’ (and property owners’) protection against the federal government.

"The ultimate authority…resides in the people alone."

James Madison

This is where the Second Amendment came in. Madison ensured that states or citizens would not be deprived of the ability to protect themselves by forming a militia against an overbearing national government, just as they had done against the British crown. Such a situation envisioned a community banding together to resist an army of oppression. The Second Amendment actually says in its final version: “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” The amendment, then, was about a militia and “the people” (in other words, the community) protecting the state, not people as individuals.

Though Madison believed that the existence of the Constitution would ensure that basic rights were protected under a federal government, he formulated the Bill of Rights as an extra measure to counteract the power of the majority in a democracy.

Individual self-defense

Madison was not talking about individuals carrying arms to defend themselves against individual criminal acts. Yet that is how his words in the Second Amendment have come to be used, and many Americans now claim that the right to carry guns is enshrined in the Constitution—challenging any move to institute gun controls as unconstitutional.

Attempts to overturn this interpretation in the courts have repeatedly met with failure, with the insistence that the Constitution upholds citizens’ rights to bear arms in defense of themselves as well as the state. Many argue even further that, regardless of Madison’s intentions, owning and carrying a gun should be considered a basic freedom. A century before Madison’s bill, English philosopher John Locke, in identifying the right to self-defense as a natural right, took his cue from an imagined “natural” time before civilization. Just as a wild animal will defend itself with violence if cornered, so, Locke argues, may humans. The implication is that government is in some way an unnatural imposition from which people need protection. In retrospect, some commentators have put a Lockean gloss on the Bill of Rights, and assume that it is confirming self-defense by violent means as a natural, inalienable right.

However, it seems possible that Madison and his fellow Founding Fathers were more in tune with Scottish philosopher David Hume’s view of government than with Locke’s. Hume is too pragmatic to pay much attention to the idea of a natural time of freedom before rights were curtailed by civilization. For Hume, people want government because it makes sense, and rights are something negotiated and agreed upon, like every other aspect of law. So there is nothing fundamental about the right to bear arms—it is simply a matter that people generally agree about, or not. According to Hume, freedoms and rights are just examples of tenets on which people concur—and perhaps decide mutually to enshrine in law to ensure that they are adhered to. Taking this view, there is no fundamental principle at stake in the right to bear arms—rather, it is a consensus. And consensus does not necessarily require a democratic majority.

Lasting controversy

Gun control remains a hot issue in the US, with powerful lobbies—such as the National Rifle Association (NRA)—campaigning against any restrictions on gun ownership at all. Those against gun control appear to have the upper hand, with most states allowing people to own firearms. Still, there are very few states where gun ownership is entirely unregulated, and there are arguments over whether, for instance, people should be allowed to carry concealed guns. The high level of gun crime in the US, and the increasing frequency of mass murders—such as the cinema killings in Aurora, Colorado in July 2012—have led many to question whether unrestricted ownership of firearms is appropriate in a nation that is no longer a frontier state.

It is remarkable that Madison’s Bill of Rights is still, with only a few changes, at the heart of the US political system. Some, maybe even Madison himself, would argue that a good government would have protected these rights without need of a bill. Yet the Bill of Rights remains perhaps the most powerful meld of political theory and practice ever devised.

Natural self-defence as used by wild animals against attack is cited by exponents of natural law to justify the right of an individual to defend themselves by any means.

JAMES MADISON

James Madison, Jr. was born in Port Conway, Virginia. His father owned Montpelier, the largest tobacco plantation in Orange County, worked by 100 or so slaves. In 1769, Madison enrolled at the College of New Jersey, now Princeton University. During the Revolutionary War, he served in the Virginia legislature and was the protégé of Thomas Jefferson. At 29, he became the youngest delegate to the Continental Congress in 1780, and gained respect for his ability to draft laws and build coalitions. Madison’s draft—the Virginia Plan—formed the basis of the US Constitution. He cowrote the 85 Federalist Papers to explain the theory of the Constitution and ensure its ratification. Madison was one of the leaders of the emerging Democratic-Republican party. He followed Jefferson to become the fourth US president in 1809, and held the office for two terms.

Key works

1787 United States Constitution

1788 Federalist Papers

1789 The Bill of Rights

See also: Cicero • Thomas Hobbes • John Locke • Montesquieu • Pierre-Joseph Proudhon • Jane Addams • Mahatma Gandhi • Robert Nozick