IN CONTEXT

Anti-colonial nationalism

Non-violent resistance

5th–6th centuries BCE Jainist teachings stressing nonviolence and self-discipline develop in India.

1849 Henry David Thoreau publishes Civil Disobedience, defending the morality of conscientious objection to unjust laws.

1963 In his “I have a dream” speech in Washington DC, civil rights leader Martin Luther King outlines his vision of black and white people living together in peace.

2011 Peaceful protests in Cairo’s Tahrir Square lead to the overthrow of Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak.

In the worldwide empires that European powers built from the 16th century onward, it was the example of the imperialists themselves that ultimately gave rise to the nationalist movements that sprang up in opposition to colonial rule. Witnessing the colonizers’ strong sense of national identity, based on European ideas about nations and the importance of sovereignty within geographical borders, eventually ignited a desire for nationhood and self-determination in the colonized peoples. However, the lack of economic or military strength led many anticolonial movements to develop distinctly non-European modes of resistance.

A spiritual weapon

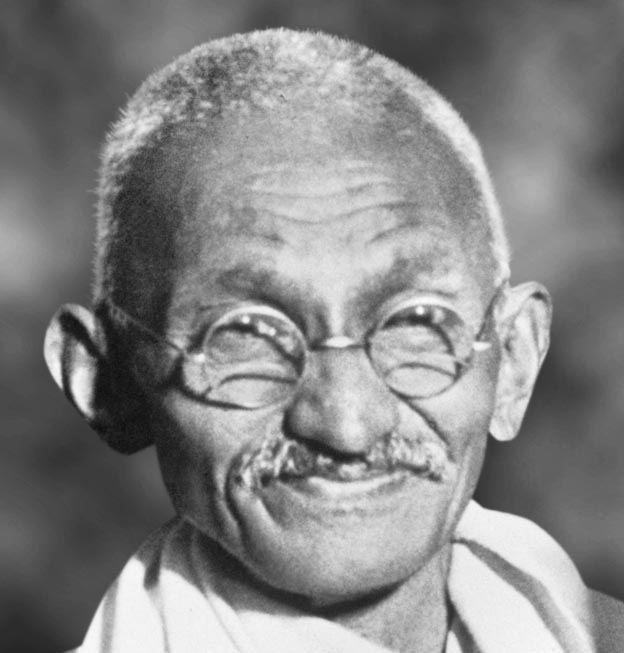

In India, the fight for independence from the UK in the first half of the 20th century was characterized by the political and moral philosophy of its spiritual leader, Mohandas Gandhi, more commonly known by the honorific title “Mahatma,” meaning “Great Soul.” Although he believed in a strong democratic state, Gandhi held that such a state could never be won, forged, or held by any form of violence. His ethic of radical nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience, which he named satyagraha (“adherence to truth”), focused a lens of morality and conscience on the tide of anticolonial nationalism that was transforming the political landscape of the 20th century. He described this method as a “purely spiritual weapon.”

Gandhi believed that the universe was governed by a Supreme Principle, which he called satya (“Truth”). For him, this was another name for God, the one God of Love that he believed to be the basis of all the great world religions. Since all human beings were emanations of this divine Being, Gandhi believed that love was the only true principle of relations between humans. Love meant care and respect for others and selfless, lifelong devotion to the cause of “wiping away every tear from every eye.” This enjoined ahimsa, or the rule of harmlessness, on Gandhi’s adherents. Although a Hindu himself, Gandhi drew on many different religious traditions as he developed his moral philosophy, including Jainism and the pacifist Christian teachings of Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy, both of which stressed the importance of not causing hurt to any living creature.

Political ends

Gandhi’s ideology was an attempt to work out the rule of love in every area of life. However, he believed that the endurance of suffering, or “turning the other cheek” to abusive treatment at the hands of an individual or a state, as opposed to violent resistance or reprisal, was a means to a political end as well as a spiritual one. This willing sacrifice of the self would operate as a law of truth on human nature to secure the reformation and cooperation of an opponent. It would act as an example to wider society—political friend and foe alike. Home rule for India would be, for Gandhi, the inevitable outcome of a mass revolution of behavior based on a rich brew of peaceful transcendental principles.

South African activist

Gandhi’s first experience of opposing British rule came not in India, but in South Africa. After training as a lawyer in London, he worked for 21 years in South Africa—then another British colony—defending the civil rights of migrant Indians. It was during these years that he developed his sense of “Indianness,” which he saw as bridging every divide of race, religion, and caste, and which underpinned his later vision of a united Indian nation. In South Africa, he witnessed firsthand the social injustice, racial violence, and punitive government exploitation of colonial rule. His response was to develop his pacifist ideals into a practical form of opposition. He proved his gift for leadership in 1906 when he led thousands of poor Indian settlers in a campaign of disobedience against repressive new laws requiring them to register with the state. After seven years of struggle and violent repression, the South African leader, Jan Christiaan Smuts, negotiated a compromise with the protestors, demonstrating the power of nonviolent resistance. It might take time, but it would win out in the end, shaming opponents into doing the right thing.

In the years that followed, Gandhi had considerable success in promoting his idea that non-violent resistance was the most effective resistance. He returned to India in 1915 with an international reputation as an Indian nationalist, and soon rose to a position of prominence in the Indian National Congress, the political movement for Indian nationalism. Gandhi advocated the boycott of British-made goods, especially textiles, encouraging all Indians to spin and wear khadi, or homespun cloth, in order to reduce dependence on foreign industry and strengthen their own economy. He saw such boycotts as a logical extension of peaceful noncooperation and urged people to refuse to use British schools and law courts, to resign from government employment, and to eschew British titles and honors. Amid increasing excitement and publicity, he learned to distinguish himself as an astute political showman, understanding the power of the media to influence public opinion.

Gandhi was influenced by Jainism, a religion whose central principle is to avoid harming living things. Jain monks wear masks so that they do not inadvertently breathe in insects.

Public defiance

In 1930, with the British government refusing to respond to Gandhi’s congressional resolution calling for Indian dominion status, full independence was unilaterally declared by the Indian National Congress. Soon after, Gandhi launched a new satyagraha against the British tax on salt, calling on thousands to join him on the long march to the sea. As the world watched, Gandhi picked up a handful of the salt that lay in great white sheets along the beach, and was promptly arrested. Gandhi was imprisoned, but his act of defiance had publicly demonstrated the unjust nature of British rule in India to commentators around the world. This carefully orchestrated act of nonviolent disobedience began to shake the hold of the British empire on India. Reports of Gandhi’s campaigns and imprisonment appeared in newspapers all over the world. German physicist Albert Einstein said of him: “He has invented a completely new and humane means for the liberation war of an oppressed country. The moral influence he had on the consciously thinking human being of the entire civilized world will probably be much more lasting than it seems in our time, with its overestimation of brutal violent forces.”

"A religion that takes no account of practical affairs and does not help to solve them is no religion."

Mahatma Gandhi

Thousands joined Gandhi’s protest against the tax on salt imposed by the British. They marched to the coast at Dandi in Gujarat in May 1930 to gather salt water and make their own salt.

Gandhi believed that the nonviolent means used to achieve his end were just as important as the end itself. He used the example of procuring a person’s watch to illustrate his point.

Strict pacifism

However, Gandhi’s absolute confidence in his doctrine of non-violence sometimes seemed unbalanced when he applied it to the conflicts unfolding in the wider world, and this earned him criticism from many quarters. “Self-suffering endurance” appeared sometimes to require mass suicide, as shown by his weeping plea to the British Viceroy of India that the British give up arms and oppose the Nazis with spiritual force only. Later, he criticized Jews who had tried to escape the Holocaust or had fought back against German repression saying, “The Jews should have offered themselves to the butcher’s knife. They should have thrown themselves into the sea from cliffs. It would have aroused the world and the people of Germany.” Criticism also came his way from the left, and British Marxist journalist Rajani Palme Dutt accused him of “using the most religious principles of humanity and love to disguise his support of the property class.” Meanwhile, British prime minister Winston Churchill attempted to dismiss him as a “half-naked fakir.”

Whatever the limits of their application in other situations, Gandhi’s methods were certainly successful in eventually winning independence for India in 1947, although he bitterly opposed the Partition of India into two states split along religious lines—predominantly Hindu India and Muslim Pakistan—which led to the displacement of millions of people. Soon after Partition, Gandhi was assassinated by a Hindu nationalist who accused him of appeasing Muslims.

"Christ gave us the goals and Mahatma Gandhi the tactics."

Martin Luther King

Today’s rapidly industrializing India is a far cry from the rural romanticism and asceticism of Gandhi’s political ideals. Meanwhile, the ongoing tension with neighbor Pakistan shows that Gandhi’s belief in an Indian identity that transcended religion has ultimately been unfulfilled. The caste system, which Gandhi had steadfastly opposed, also maintains a strong hold on Indian society. However, India remains a secular, democratic state, which still aligns with Gandhi’s fundamental belief that it is only through peaceful means that a just state can emerge. His example and methods have been taken up by activists around the world, including civil rights leader Martin Luther King, who credited Gandhi as the inspiration for his peaceful resistance to racially biased laws in the US in the 1950s and 60s.

Forms of nonviolent protest, from blocking roads to boycotting goods, have become popular and powerful methods of civil disobedience in today’s political world.

MAHATMA GANDHI

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born on October 2, 1869, to a prominent Hindu family in Porbandar, part of the Bombay Presidency in British India. Gandhi’s father was a senior government official and his mother a devout Jain.

Gandhi was married at the age of just 13. Five years later, his father sent him to London to study law. He was called to the bar in 1891 and set up a law practice in South Africa, defending the civil rights of Indian migrants. While there, Gandhi embarked upon a strict course in brahmacharya, or Hindu self-discipline, beginning a life of asceticism. In 1915, he returned to India, where he took a vow of poverty and founded an ashram. Four years later, he became head of the Indian National Congress. He was killed on his way to prayer by a Hindu extremist who blamed him for the Partition of India and the creation of Pakistan.

Key works

1909 Hind Swaraj

1929 The Story of My Experiments with Truth

See also: Immanuel Kant • Henry David Thoreau • Peter Kropotkin • Arne Naess • Frantz Fanon • Martin Luther King