3

The Power of the Message

IN SPITE OF all the progress we've made in becoming a truly diverse society, there are still lingering questions—spoken and unspoken— about the abilities of certain groups Are individuals from certain schools, cultures, or a particular socioeconomic status better prepared for the rigors of a career? Can women make the tough calls that are necessary at the highest corporate levels? Can professionals of color lead effectively in traditionally white organizations? At one time or another, most of us have had to confront stereotypes like these in order to secure the opportunities and recognition we deserve.

Having to prove we are capable and committed can be frustrating and draining, but the greater harm happens when we let others' doubts creep into our psyches—when we begin to seriously question whether we're smart enough or bold enough or creative enough to attain our goals. Internalizing those doubts begins to undermine our confidence, and when that happens, our development is at risk.

Almost all of us can recount a situation where our abilities were questioned and the doubts affected our mindset and effort. I have a particularly painful and striking example from early in my career as a human resources manager. I felt I had conquered the demands of my position at the time, and I was eager for more challenges and new responsibilities. So I was excited when Bob, my vice president, announced he was recruiting for a new director‐level position. I thought this was a chance to advance my career.

I still vividly remember discussing the opportunity with Bob and the sting of being told I was “intellectually weak” and didn't “have the bandwidth for the job.” He told me that my current position was the peak of my potential and that he expected me to assist him in recruiting and hiring the director who would eventually become my new boss.

I was devastated. And I accepted that what he had said to me was true. I began forgetting simple tasks. I was reluctant to speak up in meetings for fear of appearing dumb. I began to question whether I was cut out for corporate life. Every day was a struggle to get out of bed to come to work, and I felt pretty defeated about where my life might go.

Fortunately for me, Bob was replaced by Susan, a vice president from our corporate finance department. Susan had never worked in the human resources division before, so the first thing she did was to reach out to her direct reports to ask for our collective experience to assist her in building the best department possible. I remember thinking, “She assumes I have something to offer.” With just that little acknowledgment of my value, it got easier to get out of bed in the morning.

Susan also revealed that she was aware of my interest in the new director position and didn't want to make a decision until she had given me an opportunity to demonstrate my capabilities. She even went one step further: she reassured me she'd partner with me to develop the needed skills. I can't tell you how awesome I felt after that meeting. Not only was Susan giving me a chance, but she was actively supporting my success.

Susan was true to her word. She took the time to explain the big picture behind her decisions. She asked me for my perspective. She gave me assignments that stretched me and increased my visibility among other senior executives.

As you can imagine, my confidence returned with this kind of partnership. Coming to work was fun again. I worked doubly hard to be effective, and I did everything in my power to aid her success in her new role. You should have seen the tears in my eyes when I was promoted to director six months later.

As I think back on my experience now, I'm struck by the realization that I had the same set of talents and potential when Bob chopped away at my belief in myself as I did when Susan positioned me for success. The difference was that I let Bob's assessment of my abilities destroy my confidence and undermine my efforts. For a while, I let his negative expectations determine who I was and how I performed. His messages hit some vulnerability in me at a time when there weren't a lot of young Black men in corporate America and I was still struggling to establish myself and ground my professional identity. I often wonder where my career would have gone if Bob hadn't been replaced.

I've heard countless stories like my own. Some professionals recount a positive ending; others are still struggling to let go of negative beliefs they've internalized about themselves, sometimes going back to childhood. It is inevitable that we will experience some level of difficulty when we're stretching ourselves to take on new and demanding challenges. And it's probable that we will experience some level of judgment and doubts from others. We can't control the assumptions others make about us, but we can control the impact of these messages. We can be intentional about how we respond when others expect less of us than we are truly capable of. My dream is for no one to be dependent on a manager like Susan appearing on the scene to perform at his or her best.

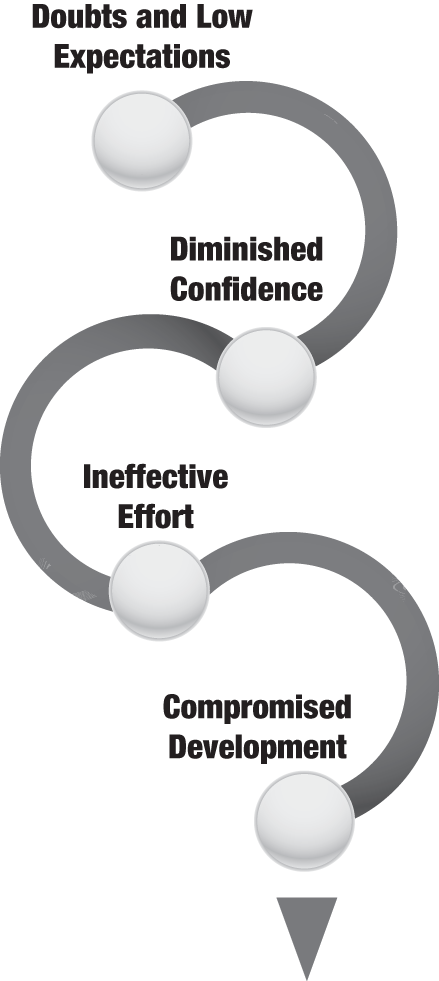

A Downward Spiral

Here's the pattern that typically emerges when someone overtly or subtly raises doubts about our abilities or expresses low expectations in an area where we're vulnerable: The doubts and low expectations erode confidence and undermine our efforts. Because our effort is compromised, our performance is less likely to be satisfactory, which confirms the original low expectations—in our minds and in the minds of others. (See Figure 3.1.) The cycle can then become self‐sustaining because we've internalized the low expectations. Even after there's no longer a Bob in the picture, we doubt ourselves and our capabilities.

Low expectations are seldom as stark as those that I received from Bob. Usually, they are more subtle, but they can be equally capable of damaging your belief in yourself. Your manager might ask who helped you with a project or why you think you can lead a team. Other times, you might detect doubt in a colleague's voice, notice that you're not considered for opportunities as regularly as your peers, or observe that few professionals like you have been successful in a particular role or at a particular level of leadership. Sometimes it's just the feeling of invisibility; no one notices you. You have the title but not the authority; people make decisions without you.

Some of the negative messages you receive might even be well intentioned. Family or friends advise you not to take a promotion and “avoid all that stress.” Or colleagues tell you to pass on a challenging opportunity because “it will never get you anything but trouble.” These types of counsel might be intended to protect us from disappointment or failure, but they nevertheless convey a negative assessment of our potential for success and discourage the risk‐taking that promotes growth.

Sometimes negative external messages have minimal impact. We become frustrated or angry that we have to address them again and again, but overall, they don't affect our confidence in our capabilities or our commitment to developing them.

Other times, we are vulnerable. We remember a parent or teacher who doubted us. We recall a past failure or difficulty. We focus on some problem we're currently having and wonder whether the low assessment of our ability could be true. Or perhaps at some level we've absorbed the stereotyped messages. The result is that our confidence in our ability to be successful is compromised. We start to doubt ourselves.

When we begin to wonder whether others' doubts about our abilities could be true, the resulting anxiety and tension impede our best efforts.

I was reminded of this when a colleague of mine was agonizing about her ten‐year‐old son's batting slump in Little League. He'd had several at‐bats where he missed the ball and struck out. At first, he was disappointed. But now his fear of not hitting the ball had begun to overwhelm his ability to react to a pitch. He was stuck in a downward spiral: strikes produced anxiety, which crippled his ability to perform, in turn producing more anxiety and more strikes. And because he was in a slump, the coach wasn't playing him as much since he couldn't count on him to get a hit.

Low expectations can create the professional equivalent of a batter's slump. Our focus is divided between worrying about failing and actually working on the challenges of the situation. So our effort is compromised—and ultimately so is the outcome.

Then, faced with less than stellar performance, we have to explain our lack of success. We've already been primed to view the situation as one where there's some deficiency on our part. So we're likely to confirm in our minds the initial negative expectations we received from others. The downward spiral is now complete: we've internalized the original low expectations.

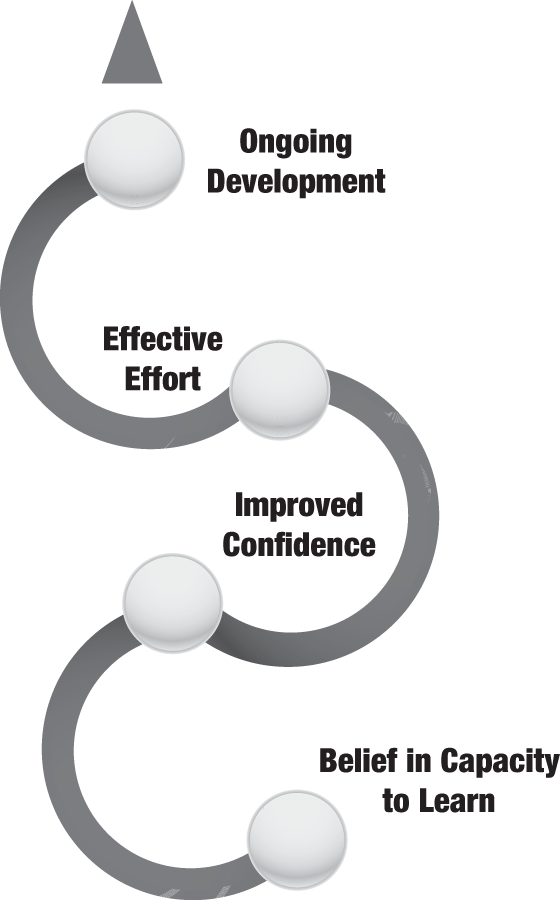

Creating an Upward Spiral

How do we break this downward spiral and create an upward one? How do we maintain the confidence we need to pursue our development? In short, by embracing the capacity‐building mindset—the belief that we can learn any skill, provided we use failure as feedback and invest effort to improve. (See Figure 3.2.) A capacity‐building mindset makes us less vulnerable to external questions about our capabilities. It allows us to focus on the effort required to learn and develop new skills.

I recently coached Alberto, an Argentinean by birth, who had made a presentation to a group of leaders. When it wasn't going well, his manager jumped in and took over the discussion and then gave him some pointed criticism about how he handled the group. As a result, Alberto concluded his accent and poor communication skills prevented him from taking on any leadership roles that involved public speaking. (Notice the big leap he had made from a presentation that didn't go well to assessing his leadership potential in general!) Our conversations helped him make a more objective assessment of his situation. He realized that it was more accurate to say, “Day to day, I communicate effectively. However, when I'm nervous, I speak too quickly, and it's hard for others to understand me. I need to practice the strategies that help me be at ease in front of a group.” I encouraged him to look for new opportunities to practice his presentation skills rather than prematurely closing doors. Once he builds up his confidence, he'll be ready to take on more visible leadership roles.

You can't eliminate stereotypes and low expectations. You can, however, become more aware of how these subtle messages affect your confidence

The greater your awareness of the dynamics created by low expectations, the better you can intervene to shore up your confidence and commitment to develop your abilities. Awareness gives you greater choice in how you respond. Will you succumb to the low expectations of others or choose to believe in your potential for learning and development?

Tell‐Tale Signs of the Impact of Low Expectations

Often, the first signal that low expectations have affected your self‐confidence is that you avoid or procrastinate on some task. You might even devise a variety of seemingly reasonable explanations for your behavior. You tell yourself that the challenge in front of you really isn't an area of interest, it's not important to your advancement, or you don't have time. If you're serious about your development, get serious about realizing when you're making excuses or rationalizations rather than confronting your fears and pursuing your development.

Over the years, I've asked many groups about their behavior when they are questioning their capacity to succeed. According to one group, at such a time they are most likely to:

- Stay busy but never find time for the things that are most critical

- Avoid the project or withdraw

- Tell themselves their family needs them and they shouldn't take on a new opportunity

- Not take any risks and play it safe

- Take unrealistic risks so they can't be blamed if they fail

- Dress, talk, or act in a way that puts others off

- Avoid feedback and deny that there are areas in which they need to improve

One of the women in the group even confided that she had four children—each five years apart. Every time her youngest child was entering kindergarten, she acknowledged that she would contemplate returning to the paid workforce. Although the prospect of returning to work excited her, it also scared her. So, in retrospect, she realized she resolved the issue by becoming pregnant. Certainly with a new baby on the way, it was no time to face the uncertainty of a new job.

Deciding to have a baby, turn down an assignment, or stay in the same job is not necessarily an indication that you're avoiding a challenge, but it could be. If you're serious about advancing your career and going after what's important to you, be honest with yourself. Are you making excuses for why you're not investing fully in some endeavor when in reality you're doubting yourself or fearing the possibility of failure? Such misgivings are normal; we all experience them. However, you can choose how you respond. Will you let your possibilities be driven by others' low expectations and your own fears? Or will you take the risk of engaging in challenging opportunities that feed your growth and development?

Each of us has to decide what we want to accomplish and make decisions and choices that honor those goals. We all have to develop the emotional and intellectual resilience to confront stereotypes, embrace new and challenging tasks, and risk failure. We have to trust that we can develop the skills necessary to be successful in whatever endeavors we undertake. For only by making a strong commitment to our development and taking those risks can we develop the skills that prove to ourselves, and others, that we have the capacity to be the person we dream of being.