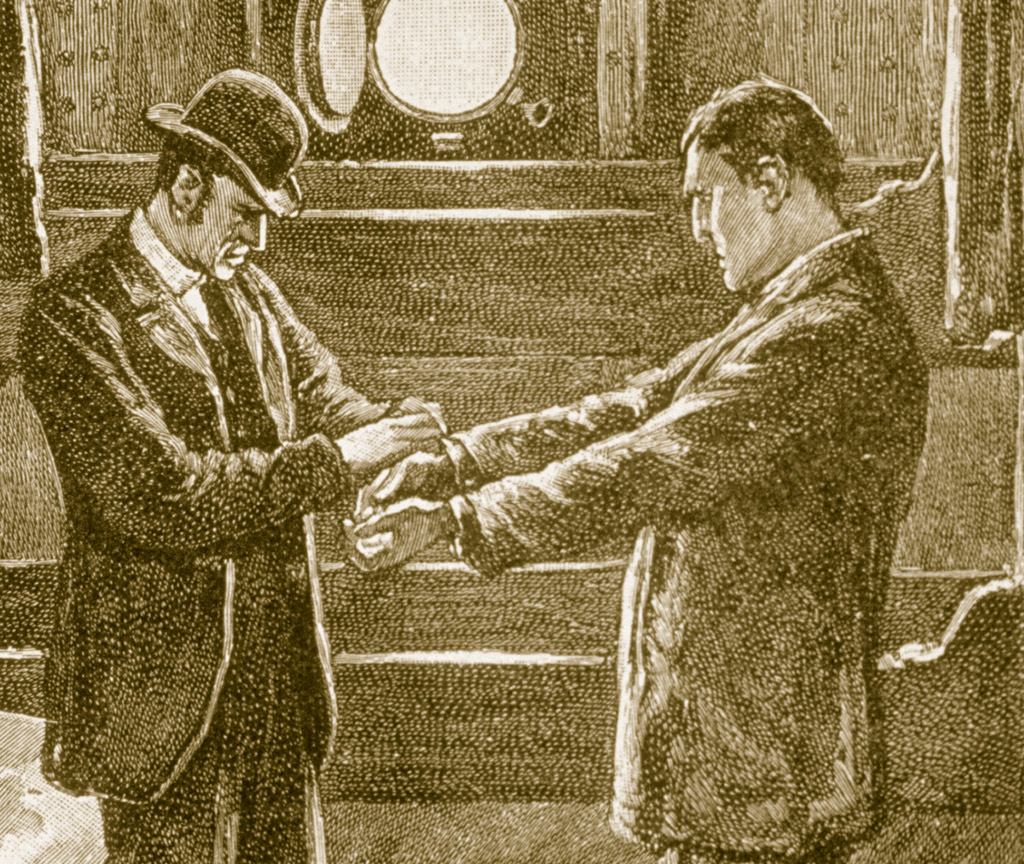

Inspector G. Lestrade is the Scotland Yard detective who appears repeatedly throughout the Holmes canon. Many other police detectives make a fleeting appearance, from Inspector Stanley Hopkins in “The Adventure of Black Peter” to Inspector Bardle in “The Adventure of the Lion’s Mane”, but Lestrade is the only persistent presence. First appearing in A Study in Scarlet in 1887, Lestrade is still there in “The Adventure of the Three Garridebs”, which Conan Doyle wrote 37 years later.

Conan Doyle seems to have gotten Lestrade’s name from a fellow medical student at Edinburgh, Joseph Alexandre Lestrade, and the initial “G” may be an echo of the Prefect of Police known only as “G___” in Edgar Allan Poe’s story The Purloined Letter (1845). Watson describes the inspector as “a little sallow rat-faced, dark-eyed fellow” and later as “a lean, ferret-like man, furtive and sly-looking.” Very little else is known about Lestrade, but he is probably part of the new breed of tenacious professional policemen who made their way up through the ranks from humble beginnings—the kind first depicted in fiction in the form of Inspector Bucket in Charles Dickens’ Bleak House (1853) and Inspector Cuff in Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone (1868).

Inspector Lestrade arresting Jim Browner in “The Cardboard Box,” first published in the UK in The Strand Magazine (1893).

Fact or fiction?

Both Bucket and Cuff were based on the real-life Detective Inspector Jonathan “Jack” Whicher (1814–1881), one of the eight original members of the Detective Branch set up at Scotland Yard in 1842. Whicher reached the pinnacle of his fame with the infamous Constance Kent murder mystery in 1860, recalled in Kate Summerscale’s 2009 book The Suspicions of Mr. Whicher. Readers both of the fictional stories and of the real-life crime reports at the time got a particular frisson from the way such lowly men probed behind the facade of well-to-do respectability to lay bare their corruption. Holmes, of course, has a more aristocratic brilliance, and when he first meets Lestrade, he can barely conceal his low opinion. “[Gregson and] Lestrade are the best of a bad lot. They are both quick and energetic, but conventional—shockingly so…” His ridicule soon becomes so marked it seems almost snobbery. But Conan Doyle may have been drawing inspiration from real life.

"I really cannot undertake to go about the country looking for a left-handed gentleman with a game leg. I should become the laughing-stock of Scotland Yard."

Inspector Lestrade

A tarnished reputation

By the 1880s, Scotland Yard’s reputation, so bright in Whicher’s day, had been tarnished by the way in which Inspector John Shore and his fellow detectives were given the runaround by Adam Worth, the real-life criminal mastermind who was one of the inspirations for Conan Doyle’s Moriarty . Worth made Shore look flat-footed and incompetent, and Shore never caught his man despite years of dogged pursuit. Scotland Yard’s reputation hit another low in 1888, when they failed to make any headway with the appalling Jack the Ripper murders.

Mutual respect

Over the years, however, Holmes’s contemptuous attitude toward Lestrade seems to mellow. At first, Lestrade doesn’t think much of Holmes either. So, perhaps sensing Holmes’s ridicule, he declares himself to be a practical detective who deals in facts—in contrast to the abstract thinking of amateurs like Holmes. But as he sees Holmes solve case after case, he comes to admire the detective’s methods. Holmes, in turn, begins to respect some of Lestrade’s qualities, and allows the inspector to take the credit for his deductions.

In “The Cardboard Box”, Holmes admits that Lestrade is “tenacious as a bulldog when he once understands what he has to do, and indeed, it is just this tenacity which has brought him to the top at Scotland Yard.” And when Holmes comes back from the dead in “The Adventure of the Empty House”, he trusts Lestrade enough to let him in on his secret. Lestrade returns the compliment, saying, “It’s good to see you back in London, sir.” By the time of “The Adventure of the Six Napoleons”, it turns out that Lestrade regularly drops by at 221B Baker Street with updates and for advice. Lestrade even admits to a genuinely touched Holmes that “… we are very proud of you [down at Scotland Yard], and if you come down to-morrow there’s not a man, from the oldest inspector to the youngest constable, who wouldn’t be glad to shake you by the hand.”

THE BAKER STREET IRREGULARS

Despite appearances, Holmes rarely works entirely alone. In a number of investigations the detective is aided by his invisible army of helpers—the motley crew of street urchins known as the Baker Street Irregulars. In A Study in Scarlet, Watson describes them as “half a dozen of the dirtiest and most ragged street Arabs that ever I clapped eyes on,” but Holmes knows their value, calling them “the Baker Street division of the detective police force.” Shabby they may be, but for the price of a shilling a day, they can “go everywhere and hear everything.” No one but Holmes pays any attention to these dirty little children, led by a boy named Wiggins, but in many stories they provide crucial information. Besides the Irregulars, Holmes picks various other more humble members of society to help him—from the 14-year-old messenger Cartwright, who goes through hotel garbage cans in The Hound of the Baskervilles, to Billy the pageboy in The Valley of Fear.