IN CONTEXT

Novel

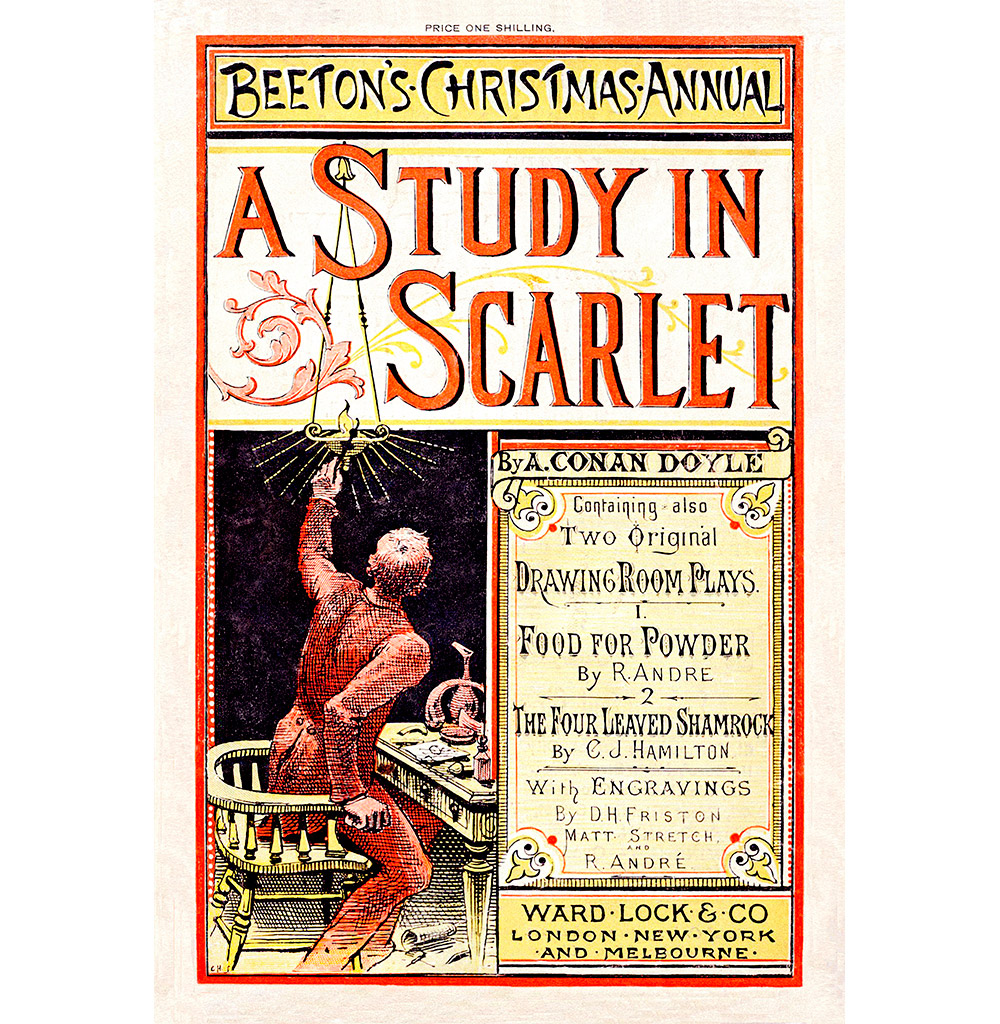

UK: Beeton’s Christmas Annual, December 1887

Ward, Lock & Co. July 1888

Stamford Former medical colleague of Watson’s.

Inspectors Lestrade and Tobias Gregson Scotland Yard policemen.

Enoch J. Drebber Elder of the Mormon church.

Joseph Stangerson Mormon elder, and Drebber’s secretary.

Jefferson Hope Young American.

Constable John Rance Policeman.

Wiggins Leader of a gang of London street urchins.

Madame Charpentier Drebber’s landlady.

Arthur Charpentier Naval officer, and son of Madame Charpentier.

Alice Charpentier Madame Charpentier’s daughter.

John Ferrier Wanderer found by Mormons.

Lucy Ferrier John Ferrier’s daughter.

Brigham Young Real-life leader of the Mormon church.

The year is 1880 and military surgeon Dr. John H. Watson has been discharged from the army after being wounded in Afghanistan. Back in London and living on a meager army pension, he is looking for someone to share lodgings with. An old colleague of Watson, Stamford, introduces him to Sherlock Holmes (who calls himself the world’s only “consulting detective”), and the two men take up rooms at 221B Baker Street.

On receiving a request for help from the police, Holmes invites Watson to accompany him. The pair meet inspectors Gregson and Lestrade of Scotland Yard at a house in Brixton, where a body has been found. Holmes deduces from the sour smell on the man’s lips that he has been poisoned. Documents identify him as Enoch Drebber, a US citizen, who is traveling with his secretary, Stangerson, and lodging with a Madame Charpentier.

A woman’s wedding ring has been left at the scene, and after questioning Constable Rance, who found the body, Holmes suspects that a drunk seen hanging around the house was in fact the murderer returning to claim the ring. Other evidence suggests to Holmes that the murderer is a cabbie, although he does not reveal this to Watson.

Gregson arrests the landlady’s son, Arthur Charpentier, who had confronted Drebber over his coarse behavior toward his sister Alice. Lestrade suspects the secretary Stangerson, but finds him stabbed to death, killed while Arthur was in custody. A pillbox containing two pills is found with his body. Back at 221B, Holmes tests the pills on a sick terrier; the first is harmless, but the second kills the dog.

Learning from the police in the US that Drebber had sought protection from a man named Jefferson Hope, Holmes instructs a gang of street urchins, known as the “Baker Street Irregulars,” to trace a cabbie by that name and lure him to Baker Street. When Hope arrives, Holmes arrests him before an astonished Gregson and Lestrade.

The second section of the novel begins in Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1847. Here, it is revealed that Hope had been in love with a young woman called Lucy, who had died of a broken heart after Stangerson killed her father and she was forced to marry Drebber. The action then returns to Baker Street, where Hope reveals how he forced Drebber to make a choice between two pills; Drebber would take one while he would take the other. Drebber chose the poisoned pill and died. Hope accidentally left a keepsake, Lucy’s wedding ring, at the scene.

Hope dies of a heart condition before he can be brought to trial. To Watson’s indignation, a newspaper report gives all the credit for solving the case to Gregson and Lestrade, and barely mentions Holmes.

This is where the legend of Sherlock Holmes begins. Within the first few pages of his 1887 novel A Study in Scarlet, Conan Doyle establishes not only the eccentric and brilliant nature of his hero Holmes, but also the great detective’s essential partnership with Watson and his atmospheric vision of Victorian London. The relationship between the two men and the setting of their adventures both played an essential role in the success of the many Holmes stories that would follow.

Before the two future partners meet, Watson’s friend Stamford warns him that his potential fellow lodger “appears to have a passion for definite and exact knowledge,” and may be a bit too scientific and cold-blooded for his tastes. He tells Watson that Holmes even beats corpses in the dissecting-rooms with a stick to see how a dead body bruises after death (in mentioning this, Conan Doyle is eager to show that his sleuth is at the forefront of current developments in criminal investigation). Holmes claims to have created a new and ground-breaking process for detecting bloodstains—“the Sherlock Holmes’s test”. The fact that we never hear of this test again in any subsequent Holmes tale is not that important; Conan Doyle is simply trying to establish Holmes as the world’s first forensic detective.

Holmes the magician

But Holmes’s genius does not end with forensics. On first meeting Watson, he famously says, “You have been in Afghanistan, I perceive,” revealing his remarkable powers of observation. Holmes is able to pick out minute details, assemble them in a rational and inspired fashion, and reach a conclusion that makes him seem like a magician performing an amazing trick.

Later, in 221B, Watson picks up a magazine and reads an article on “the Science of Deduction and Analysis” which says, “By a man’s finger-nails, by his coat-sleeve, by his boot, by his trouser-knees, by the callosities of his forefinger and thumb, by his expression, by his shirt-cuffs... a man’s calling is plainly revealed.” When Watson dismisses this extract out loud as “ineffable twaddle” and “the theory of some armchair lounger,” Holmes reveals that he was the author. He then explains how he knew Watson had recently been in Afghanistan.

Watson is a doctor, and this fact, combined with the details that Holmes observes about his person and clothing, enables Holmes to deduce that Watson has recently seen service in war-torn Afghanistan that ended in an injury (see flowchart). “The whole train of thought did not occupy a second,” says Holmes, with typical immodesty.

"You have brought detection as near an exact science as it ever will be brought in this world."

Dr. Watson

Watson was injured at the Battle of Maiwand, July 1880, in the Second Anglo-Afghan war. This painting shows the British Royal Horse Artillery saving their guns from the Afghans.

Creating a legend

Conan Doyle famously based Holmes’s powers of observation on those of his mentor at Edinburgh University’s medical school, Dr. Joseph Bell. In the preface to Sherlock Holmes—The Complete Long Stories (1929), he later wrote: “Having endured a severe course of training in medical diagnosis, I felt that if the same austere methods of observation and reasoning were applied to the problems of crime some more scientific system could be constructed.”

For Holmes to appeal to the reader, Conan Doyle knew that he had to be more than a scientific cypher: he had to be enthralling in his own right. To the hypocritical society of the time—which covered up the legs of a piano for the sake of decorum, yet allowed prostitution to flourish in London’s East End—there was nothing more fascinating than a flamboyant bohemian with a disregard for convention.

Conan Doyle imbued his sleuth with an array of idiosyncrasies. The reader learns quickly that Holmes plays the violin well, and is a boxer, a swordsman, and an expert in singlestick (a martial art that uses a wooden stick). He has written a monograph on cigarette ash, keeps a tape measure and a magnifying glass in his pocket, and chatters to himself as he looks for clues.

Holmes is particularly proud of his “brain-attic,” in which he stores only essential information. As he explains: “I consider that a man’s brain originally is like a little empty attic, and you have to stock it with such furniture as you choose… It is a mistake to think that that little room has elastic walls and can distend to any extent.” When Holmes declares, to Watson’s amazement, that he did not know that the Earth orbits the sun, he tells Watson: “Now that I do know it I shall do my best to forget it.”

"The most commonplace crime is often the most mysterious, because it presents no new or special features from which deductions may be drawn."

Sherlock Holmes

The armchair detective

Holmes explains to Watson that when either the police or the many private detectives in London are stumped by a case, they come to him, and he puts them on the right track, without ever having to leave his armchair. In A Study in Scarlet more than in any of the subsequent Holmes stories, this is indeed his main role. Even before the start of the central case, Watson notes how a stream of visitors of both sexes, and all ages and classes (police inspectors, “a young girl,” “a Jew pedlar,” “a railway porter,” and an “old white-haired gentleman”), are redirected by private inquiry agencies to call upon Holmes at 221B for help.

When the main case in A Study in Scarlet does get underway, Holmes travels to the crime scene, where he investigates enthusiastically. “As I watched him,” says Watson, “I was irresistibly reminded of a pure-blooded, well-trained foxhound as it dashes backwards and forwards through the covert, whining in its eagerness, until it comes across the lost scent.” But for most of the story, the action occurs without direct involvement from Holmes, and the culprit is ultimately apprehended in his Baker Street sitting room.

Conan Doyle had to adjust this approach in later stories, allowing Holmes to go out and investigate crime, and be more of a man of action, or an “amateur bloodhound,” as Watson calls him in A Study in Scarlet. However, he never fully loses his propensity for solving crimes from the comfort of his armchair.

"…he was as sensitive to flattery on the score of his art as any girl could be of her beauty."

Dr. Watson

Watson’s vital role

Every genius needs someone more ordinary to illuminate their powers, and Conan Doyle uses Watson in this role, defining his character in the first few chapters. A man who is in the best of neither health nor spirits, Watson is friendless and has no real purpose in life at the beginning of the story. He says of himself “how objectless was my life, and how little there was to engage my attention.” He fills his time closely observing his fellow lodger, even to the extent of making a list called “Sherlock Holmes—his limits.” Many of its observations, such as that Holmes’s knowledge of literature is “nil,” prove in later stories to be inaccurate.

For a short while, Watson’s study of Holmes becomes a kind of hobby—“this man stimulated my curiosity,” he notes. But Watson very quickly assumes the role of Holmes’s full-fledged assistant in investigating the Brixton murder. Presumably it is for his own interest that Watson makes detailed notes during the investigation. However, these jottings come in very handy when he decides to write up the notes to showcase the genius of Holmes in bringing the murderer to justice. It is also this act that seals the burgeoning relationship between Holmes and Watson: transforming himself from Holmes’s companion to his biographer, Watson follows in the footsteps of the celebrated diarist James Boswell, who became the biographer of the famous writer Samuel Johnson a century earlier.

AN INSPIRATIONAL TEACHER

In his 1924 autobiography, Conan Doyle explained the inspiration behind Holmes’s amazing powers of deduction. “I thought of my old teacher Joe Bell…” At Edinburgh University’s medical school, Dr. Joseph Bell (1837–1911) had made Conan Doyle his outpatient clerk, who recalled that Bell “…often learned more of the patient by a few quick glances than I had done by my questions.”

On one occasion, Bell amazed the students gathered around him by pronouncing that the patient standing before them had served in the army, and had been recently discharged from serving as a noncommissioned officer in a Highland regiment on Barbados. Bell explained, “You see, gentlemen, the man was a respectful man but did not remove his hat. They do not in the army, but he would have learned civilian ways had he been long discharged. He has an air of authority and he is obviously Scottish. As to Barbados, his complaint is elephantiasis, which is West Indian and not British.”

Holmes’s London

While Conan Doyle recreates the streets and gardens of London in A Study in Scarlet, he had not lived in the city by that point; at the time he wrote the story he was residing in Southsea near Portsmouth, Hampshire. Instead, he must have acquired all his knowledge of the English capital from maps and gazetteers. The story takes us from Baker Street via hansom cabs to just a few well-known London areas, such as Brixton, Camberwell, Kennington Park, and Euston. Like Robert Louis Stevenson in Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886), Conan Doyle used his own home city, Edinburgh, as a model for London. The fictional Lauriston Gardens in Brixton, where the first corpse is discovered, was actually based on Lauriston Place in the Scottish capital. But interspersed with these fictional locations are real-life London landmarks, some of which still survive. For example, in the first pages of the book, Watson waits for Stamford standing at the Criterion Bar in Piccadilly, which exists to this day.

Victorian London was the backdrop for many of the Holmes tales, even before Conan Doyle moved to the city. The London settings included fictional places and real landmarks.

Forgivable faults

It is easy to find fault with A Study in Scarlet. The structure is clumsy and the mystery itself somewhat contrived, and the central villain Jefferson Hope is a fairly featureless character too. Hope lacks any of the distinguishing qualities of the charismatic villains who were to cross Holmes’s path in later stories; Conan Doyle merely uses him as a pawn to further his plot.

Another problem with A Study in Scarlet is that Holmes is such a brilliant detective that he very quickly sees to the heart of any case. Because he succeeds in solving the murder mystery and apprehending the culprit halfway through the narrative, there is little left for Holmes to do. Conan Doyle then takes the reader on a long flashback to the wilds of Utah, detailing the history of the links between Hope, Drebber, and Stangerson, and their connection to the Mormon church. As a result, Holmes necessarily disappears from the scene, and only returns in the last two short chapters.

The almost-too-quick genius of Holmes was a structural problem that Conan Doyle did not fully resolve in his later Sherlock Holmes novels either. He resorted to the flashback device once again in The Sign of Four and The Valley of Fear. And Holmes is also absent for much of The Hound of the Baskervilles, although Watson is on hand for the entire story. It may seem strange to the modern reader that Conan Doyle inserted such a long flashback into the middle of a detective story. At the time the author believed it would add an exotic appeal to the story, especially since the Mormons were very much in the news when Conan Doyle sat down to write this tale. The previous year he had attended a meeting of the Portsmouth Literary and Scientific Society, where the subject of Mormon polygamy had been addressed. By the time he was writing A Study in Scarlet, he had clearly carried out some extensive reading on the church—so much so that he felt he could even include the real-life figure of Brigham Young in his cast of characters. Conan Doyle researched various volumes for his descriptions of Utah, as he did for London in the English section of the book. But he was not sufficiently careful in his placing of the Rio Grande, which appears to have wandered from its usual setting; “These little things happen,” Conan Doyle is said to have admitted when this was pointed out to him.

"There is a mystery about this which stimulates the imagination; where there is no imagination there is no horror."

Sherlock Holmes

Seldom bettered

While it is possible to pinpoint numerous holes in the plot of this tale if you look hard enough, in the end none of these faults are what really matters. What remains in the reader’s mind is the well-defined central character of Holmes.

This brilliant characterization is most sharply demonstrated in the first part of A Study in Scarlet, in which the detective makes a succession of brilliant deductions about the corpse in the house in Brixton—a sequence that has rarely been bettered in crime fiction. On his arrival at the scene, Holmes immediately chastises Gregson for allowing everyone to trample over the pathway, destroying potentially vital footprint evidence. “If a herd of buffaloes had passed along there could not be a greater mess,” he says. Inside the house, Holmes flings himself to the ground with his magnifying glass before rattling off a list of facts to the dumbfounded Watson, Gregson, and Lestrade.

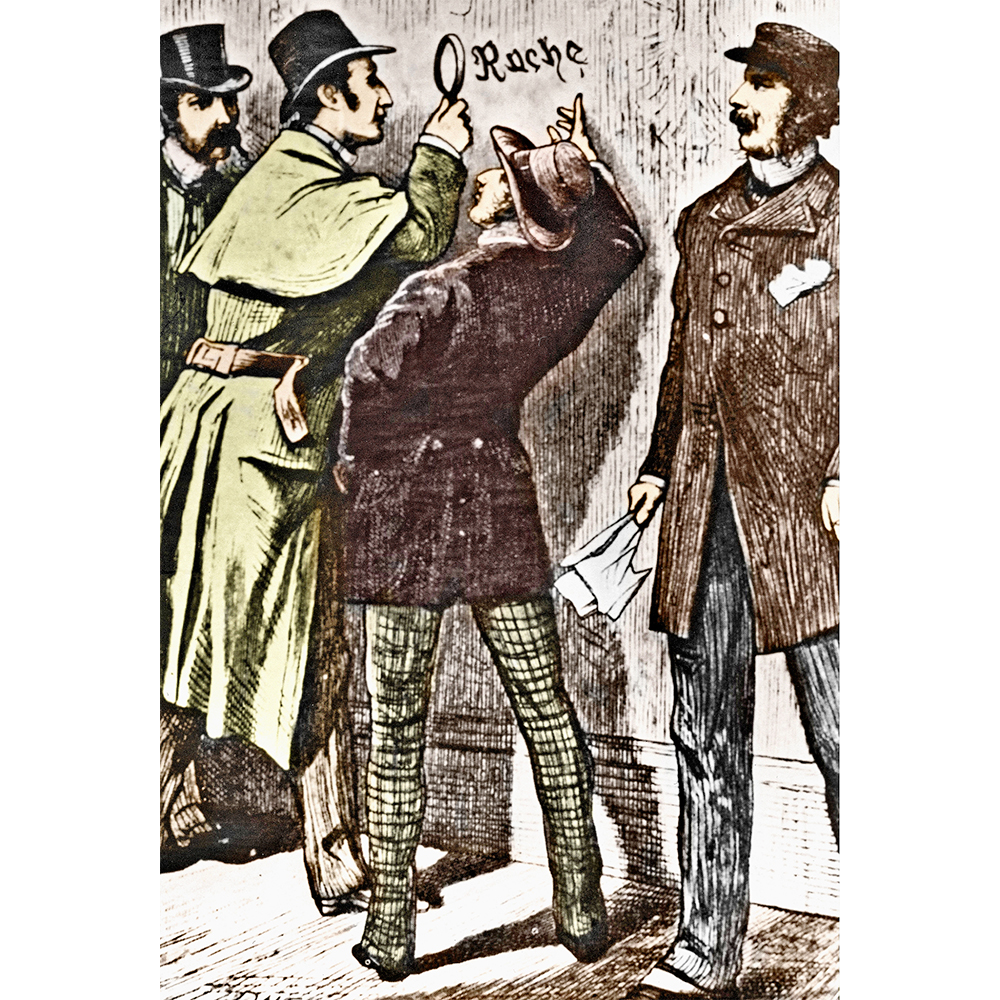

When Conan Doyle juxtaposes Holmes’s powers with Watson’s ordinariness, he makes those powers seem even more impressive; this effect is then amplified when Holmes is compared to the two bungling detectives. In their efforts to better one another, Lestrade and Gregson show just how far behind Holmes they are in terms of both acumen and perception. Neither of the two inspectors can explain the blood spattered around the murder scene, though Holmes privately surmises (correctly, it is later revealed) that the murderer must have had a nose bleed. Lestrade boasts to Gregson and Holmes that the murderer wrote “Rache” on the wall because he was disturbed before he could finish spelling the word “Rachel,” but Holmes bursts his bubble by pointing out that Rache is German for “revenge.”

Holmes carefully examines the word “Rache” written in blood on a wall at the murder scene. The way the letters have been written gives him vital clues as to the identity of the killer.

Immortality beckons

In his 1947 essay “Lear, Tolstoy and the Fool,” George Orwell wrote of Shakespeare that, like every other writer, sooner or later he will be forgotten. If the same applies to Conan Doyle, it is hard to envision his most famous creation suffering the same fate—Sherlock Holmes now has an identity beyond the pages of the novels and stories in which he first appeared.

Conan Doyle had great hopes for A Study in Scarlet, which it is believed took him only three weeks to write. But potential publishers were initially less enthusiastic: The Cornhill Magazine rejected it as reading like a cheap “shilling dreadful.” In the end, Conan Doyle accepted the derisory one-time fee of £25 for it to appear in Beeton’s Christmas Annual for 1887, which indeed cost just a shilling—five pence in modern money. To add insult to injury, its magazine debut caused barely a ripple with the reading public. Having signed away the rights to it, Conan Doyle would never receive another penny for this, his first Holmes story, even when it was reprinted in book form just over a year later. However, A Study in Scarlet has remained in print ever since, just like every other Holmes story.

Beeton’s Christmas Annual was a paperback magazine produced from 1860 to 1898. Only 10 copies of the magazine containing the first Holmes adventure are known to have survived.

BRIGHAM YOUNG

The only real-life historical figure Conan Doyle used as a character in a Holmes story was Brigham Young (1801–77). Born in Vermont, Young became a Methodist in 1823. He joined Joseph Smith’s Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints after reading The Book of Mormon, and rose to become its leader. He was called the “American Moses” after leading his followers through the desert to the “promised land” of Utah, where the Mormons founded their headquarters in Salt Lake City.

Conan Doyle’s depiction of both Young and Mormonism may be harsh, but he was never one to let facts get in the way of a good story, and at the time it was not regarded as particularly controversial. However, Conan Doyle was later criticized for defaming the faith, and years after his death, Brigham Young’s descendant Levi Edgar Young claimed that Conan Doyle had privately apologized, saying that “he had been misled by writings of the time about the Church,” and admitted that he had written “a scurrilous book.”