IN CONTEXT

Novel

US: Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine, February 1890

Spencer Blackett publishers, October 1890

Mary Morstan Young governess.

Captain Morstan Mary’s father.

Thaddeus Sholto English gentleman.

Bartholomew Sholto Thaddeus’s brother.

McMurdo Pondicherry Lodge porter and gatekeeper.

Lal Rao Butler at Pondicherry Lodge.

Mrs. Bernstone Housekeeper at Pondicherry Lodge.

Major Sholto Thaddeus’s and Bartholomew’s father.

Jonathan Small Englishman.

Mahomet Singh, Abdullah Khan, Dost Akbar Jonathan Small’s associates.

Tonga Native Andaman islander.

Athelney Jones Scotland Yard detective.

Mordecai Smith Boat owner.

Mrs. Cecil Forrester Mary Morstan’s employer.

It is 1888 and Holmes, with no case to occupy him, resorts to cocaine, to Watson’s dismay. But a puzzle for Holmes to solve appears with the arrival of Mary Morstan, the daughter of a former Indian Army officer who vanished in London 10 years earlier. At the time, his friend Major Sholto told Mary that he had no idea the captain was in the country. Four years after Captain Morstan’s disappearance, Mary began to receive an annual, anonymous gift of a pearl, and now her mysterious benefactor wants to meet her. Mary shows Holmes a paper that she found in her father’s possessions, which is marked by four crosses and the words “The sign of the four—Jonathan Small, Mahomet Singh, Abdullah Khan, Dost Akbar.”

That evening, Holmes, Watson, and Mary go to meet her benefactor, who turns out to be Thaddeus Sholto, the major’s son. He explains that his father confessed on his deathbed that Captain Morstan had come to see him the night he disappeared, but died suddenly during an argument, and the major disposed of the body. The pair of them possessed a chest full of the “Agra treasure”—but the major died before revealing to Thaddeus and Bartholomew, his brother, where it was. They had only the pearls, and argued over Mary’s claim to them; this was when Thaddeus began to send the anonymous gifts.

Thaddeus tells the group that Bartholomew has found the chest at the family home. On arrival at the house, they find Bartholomew killed by a poisoned dart and the treasure gone. Holmes deduces that a wooden-legged man, who he surmises is Small, accompanied the murderer. Altheney Jones of Scotland Yard arrests Thaddeus. Holmes discovers that Small has rented a launch, the Aurora, but is lying low. When Thaddeus provides an alibi, a chastened Jones agrees to Holmes’s request for a police boat.

That night, the Aurora roars off downriver, with Holmes, Watson, and Jones in pursuit. The “savage” fires at them with his blowpipe, but they shoot him dead and he is lost overboard. Finally, they catch up with Small, but he has thrown the treasure into the Thames. Small reveals that during the Indian Mutiny of 1857, he and Singh, Khan, and Akbar killed a man for the treasure, and hid it in Agra Fort, only to be arrested and sent to the Andaman Islands penal colony. Years later, they offered a share of the treasure to two guards, Major Sholto and Captain Morstan, in exchange for freedom. But Sholto took the treasure and betrayed them. Vowing vengeance, Small escaped with an islander (the “savage”), and tracked Sholto down.

The story ends on a happy note with Watson announcing his engagement to Mary to Holmes.

Sherlock Holmes might have remained a one-book phenomenon had it not been for an invitation to dinner at the Langham Hotel in London’s Regent Street that Conan Doyle received in August 1889. The invitation came from John Marshall Stoddart, the managing director of the successful American Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine, who was in London to launch the UK edition. Stoddart had read A Study in Scarlet and enjoyed it. More importantly, he was canny enough to realize the detective story genre was about to bloom. This awareness was prompted, perhaps, by the high sales of Fergus Hume’s 1886 The Mystery of a Hansom Cab, set in Melbourne, Australia.

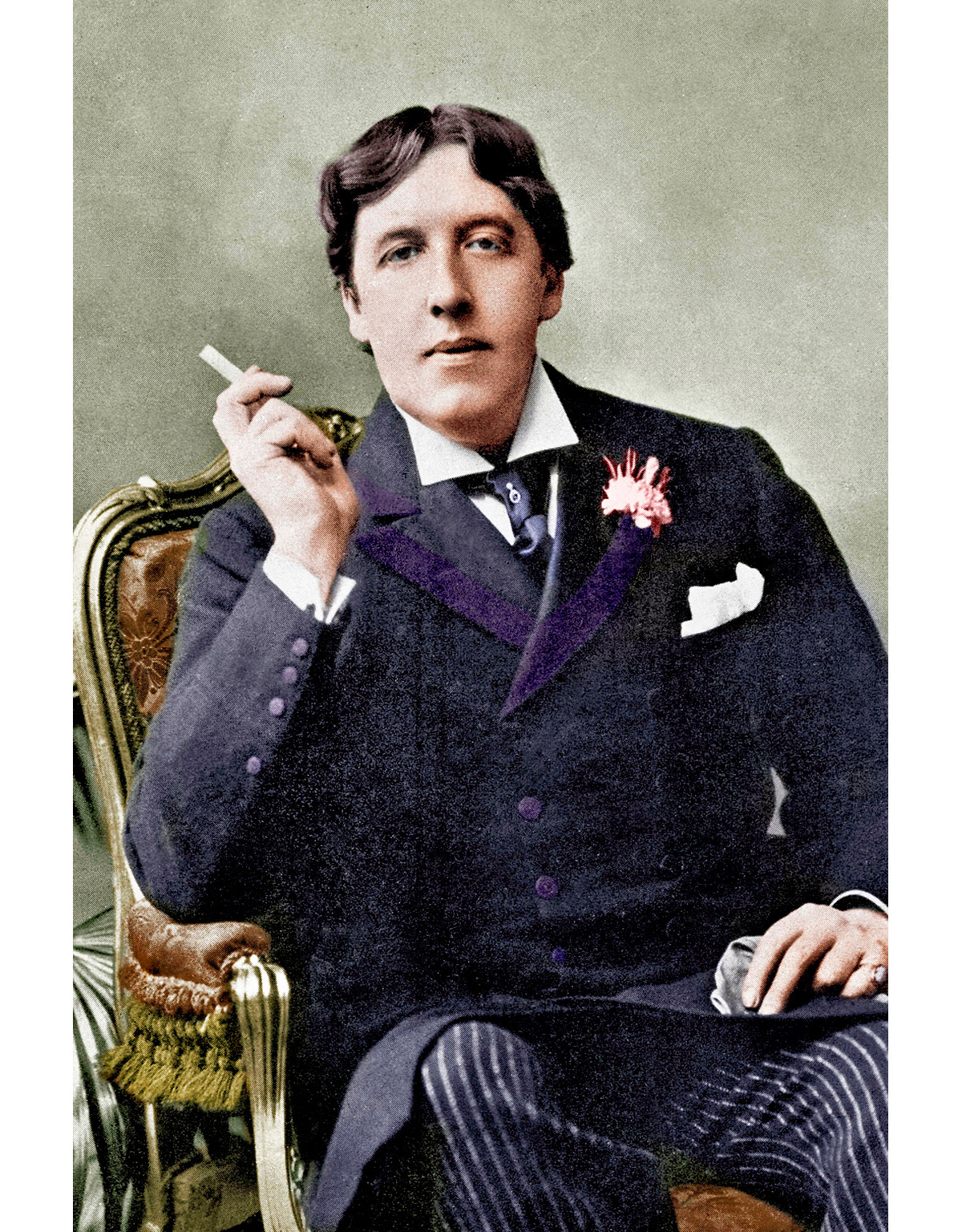

What Conan Doyle did not know was that another writer would be at the dinner: Oscar Wilde. The pair would have made very contrasting dinner guests—the conventional and serious Scottish doctor set against the flamboyant aesthete. In his autobiography, Conan Doyle called it “a golden evening.”

During the course of the dinner, Wilde and Conan Doyle were each asked to produce a novella-length mystery for the magazine. Wilde came up with The Picture of Dorian Gray. Shortly after, Conan Doyle wrote to Stoddart: “As far as I can see my story will either be called The Sign of the Six or The Problem of the Sholtos. You said you wanted a spicy title. I shall give Sherlock Holmes of A Study in Scarlet something else to unravel.”

Conan Doyle completed the book in less than a month. By then its title had become The Sign of the Four for the magazine, but when it was published later as a novel, the title became The Sign of Four.

Lippincott’s magazine gave The Sign of the Four top billing. It was renamed The Sign of Four when it was published in P. F. Collier’s Once a Week Library in the US in March 1890.

A richly drawn Holmes

Conan Doyle was by now a more accomplished writer than when he wrote A Study in Scarlet, and in The Sign of Four, he set about not only reestablishing Holmes in the consciousness of the reading public, but also adding more color, depth, and idiosyncrasies to the detective’s character.

Conan Doyle’s brush with Wilde prompted him to infuse Holmes with more bohemian extravagance than in the previous novel. In the opening paragraph of The Sign of Four, the reader discovers that the sleuth is a drug addict: “Holmes took his bottle from the corner of the mantelpiece, and his hypodermic syringe from its neat morocco case…” reports Watson. “Finally, he thrust the sharp point home, pressed down the tiny piston, and sank back into the velvet-lined armchair with a long sigh of satisfaction.”

Holmes takes both morphine and cocaine, although he seems to favor the latter. He assures Watson that he indulges in this dangerous pursuit merely to offset boredom. Only when he has a problem to solve can he really come alive and dispense with artificial stimulants.

Making Holmes a drug user was a clever way to embellish him as a character, making him immediately more edgy and interesting. For the first time, the reader also sees his theatrical side in his wonderfully convincing disguise as an old sea dog when trying to trace the Aurora, which leads Jones to observe, “You would have made an actor, and a rare one.” In A Study in Scarlet, the villain’s anonymous accomplice disguised himself as an old lady, but it is much more effective when the detective himself is in disguise. In his very next appearance, in “A Scandal in Bohemia”, Holmes disguises himself as both a drunken horse-groom and a simple-minded clergyman.

"I abhor the dull routine of existence. I crave for mental exaltation."

Sherlock Holmes

Glass and silver syringes like this were used in the 19th century. Holmes kept his in a similar case, and preferred “a seven per cent” solution of cocaine.

A literary detective

In the early days of their friendship in A Study in Scarlet, Watson made a note that Holmes’s knowledge of literature was “nil.” In this tale, however, Conan Doyle has Holmes demonstrate a broad appreciation not only for British literature, but for foreign writers too. Holmes recommends that Watson read Winwood Reade’s The Martyrdom of Man (1872)—an indictment of Christianity that was a favorite of Conan Doyle’s. Holmes quotes the German writer Goethe (1749–1832) when he disparagingly says of Jones, “Wir sind gewohnt dass die Menschen verhöhnen was sie nicht verstehen” “We are used to people making fun of things that they do not understand.”

This sophisticated literary knowledge, which may reflect Wilde’s influence on Conan Doyle, serves no plot purpose. It is simply window-dressing intended to allow Holmes to impress the reader with his accomplishments. Another echo of that “golden evening” can be seen in Watson’s portrait of Thaddeus Sholto, which is a veiled portrait of Wilde. “Nature had given him a pendulous lip,” observes Watson, “and a too visible line of yellow and irregular teeth, which he strove feebly to conceal by constantly passing his hand over the lower part of his face.” Wilde was well known for doing this.

Oscar Wilde had a sharp mind, outlandish dress and habits, and an apparent disdain for conventionalities, which left a lasting impression on the young Conan Doyle.

Holmes is a genius

Conan Doyle’s readers already knew that Holmes is clever, so it wasn’t necessary to make him a master of so many academic disciplines. But the author was pleased with his embellished portrait of the detective. He wrote to Stoddart, “Holmes, I am glad to say, is in capital form all through. I think it is pretty fair, though I am not usually satisfied with my own things.”

One aspect of Conan Doyle’s characterization that remains unchanged from A Study in Scarlet is the opportunity that he gives Holmes to show off his skills of observation and deduction before the case even gets going. Conan Doyle would continue to use this technique in many subsequent Holmes stories. For example, Holmes would test Watson’s own deductive skills using Dr. Mortimer’s stick in The Hound of the Baskervilles; Watson fails to make correct observations, but Holmes is able to determine that the doctor is young and owns a medium-sized dog. The repetition of the trick reminds readers already familiar with Holmes of his genius, while at the same time establishing it for new readers.

Here Holmes shows off his skills when he deduces from the color of the mud on Watson’s shoes and the untouched stamps and postcards on his desk that the doctor has been to the Wigmore Street Post Office to send a telegram. He goes on to examine a watch Watson has recently acquired and declares, with typical insensitivity, that it had belonged to Watson’s oldest brother, who, “taking to drink,” must have recently died.

"I cannot live without brain-work. What else is there to live for?"

Sherlock Holmes

The Sign of Four was made into a silent film in 1923, starring British actor Eille Norwood (1861–1948) as Holmes and Arthur M. Cullin as Watson. Norwood played Holmes in 47 movies.

Rival relationships

Conan Doyle adds a new dimension to the dynamic between Holmes and Watson with the arrival of the female client Mary Morstan, with whom Watson promptly falls head over heels in love. Throughout the story, the doctor behaves like a lovesick teenager, giving the lie to his claim that he has “experience of women which extends over many nations and three separate continents.” Any reader will wonder which nations and continents, and what kind of experiences. At one point he is so lovestruck that he babbles feebly to her about “how a musket looked into my tent at the dead of night, and how I fired a double-barreled tiger cub at it.” When Thaddeus thoughtlessly tells Mary that her father is dead, Watson says that he “could have struck the man across his face.” Yet when Thaddeus also reveals that Mary’s share of the treasure will be worth a quarter of a million pounds, Watson is overcome by the thought that this will put her beyond his reach. So much so that, when the hypochondriac Thaddeus asks for his professional opinion on his health, “Holmes declares,” says the doctor, “that he overheard me caution him [Thaddeus] against the great danger of taking more than two drops of castor-oil, while I recommended strychnine in large doses as a sedative.”

Much more convincing is Conan Doyle’s portrayal of the relationship between Watson and Holmes, a partnership that has moved on considerably since A Study in Scarlet. It is given real substance by the details of their domestic life together. The start of the story sees them bickering like old friends who are comfortable with each other and feel at ease in speaking their minds. Watson has no reservations at all about railing at Holmes’s drug habit, because he cares about him. The two men lounge in bachelor comfort, their rooms taking on the relaxed air of a gentlemen’s club. The only female is Mrs. Hudson, their housekeeper (named for the first time)—a motherly figure who stays in the background. Their residence, 221B Baker Street, is a well-established haven amid the hurly-burly of the metropolis.

It is sad for the reader that this cozy state of affairs seems set to end when Watson announces his engagement. Watson is about to depart for domestic bliss, leaving a solitary Holmes with his hypodermic needle—or so the reader thinks. In later Strand adventures, however, Watson is either a frequent visitor to 221B, or the story is set back in the days of his bachelorhood. Eventually, in “The Adventure of the Empty House”, we learn that Mary has died. And in “The Norwood Builder”, Watson has sold his medical practice and moved back in to 221B.

"A client to me is a mere unit, a factor in a problem. The emotional qualities are antagonistic to clear reasoning."

Sherlock Holmes

MARY MORSTAN

“What a very attractive woman!” Watson exclaims to Holmes after they first meet Mary. “Is she?” replies Holmes. “I did not observe.” Watson extols Mary’s radiant qualities, but to the reader she appears a rather unassuming figure. However, she shows strength of character when she learns that her father is dead, and has an instantly calming effect on Bartholomew Sholto’s hysterical housekeeper. “God bless your sweet, calm face!” the old woman cries. “It does me good to see you.” It is also obvious that her employer adores her. “She was clearly no mere paid dependent,” observes Watson, “but an honored friend.” The clincher is her relief on hearing that the treasure is lost.

When Watson tells Holmes of their engagement, he replies, “I really cannot congratulate you.” But he concedes that Watson has chosen well, adding that she “might have been useful in such work as we have been doing.” Clearly, her sole future role is to be a supportive wife.

In fine form

As in Conan Doyle’s previous novel, The Sign of Four is dotted with inconsistencies and minor errors. Contributing factors to this were the haste with which Conan Doyle wrote it, and his loathing of looking back at previous writings to cross-check facts and details. For example, Watson’s war wound migrates from his shoulder to his leg, and Watson now has an elder brother where before he had no living relatives. Of more concern is Conan Doyle’s questionable depiction of the indigenous Andaman islander, Tonga, who he portrays as a bestial “savage.” In an article in The Quarterly Review, 1904, Andrew Lang observed: “The [indigenous] Andamese are cruelly libelled [in The Sign of Four], and have neither malignant qualities, nor heads like mops, nor weapons.” It may be that Conan Doyle deliberately ignored the facts and made Tonga repulsive so that the reader is not distressed when “the savage” meets his demise. Yet inaccurate portrayals of “savages” were commonplace in the Victorian era, so in his portrayal of Tonga, Conan Doyle was very much a man of his times.

Overall, however, both Conan Doyle and his finest creation are on sparkling form in The Sign of Four. Holmes rattles off the names of streets as the four-wheeler taking him, Watson, and Mary to meet Thaddeus itself rattles through the night, demonstrating his intimate knowledge of London: “Rochester Row. Now Vincent Square. Now we come out on the Vauxhall Bridge Road. We are making for the Surrey side…” When they all arrive at Pondicherry Lodge, the ancestral family home of the Sholtos, Holmes once again behaves like a “trained bloodhound,” launching himself into a frenzied forensic investigation of the murder scene with the same gusto that he showed in A Study in Scarlet. Watson notes: “He whipped out his lens and a tape measure, and hurried about the room on his knees, measuring, comparing, examining…” Through his deductive brilliance Holmes makes a complete fool of Scotland Yard’s Athelney Jones, just as he did Gregson and Lestrade in the earlier tale, and manages to leave his partner Watson typically dumbfounded.

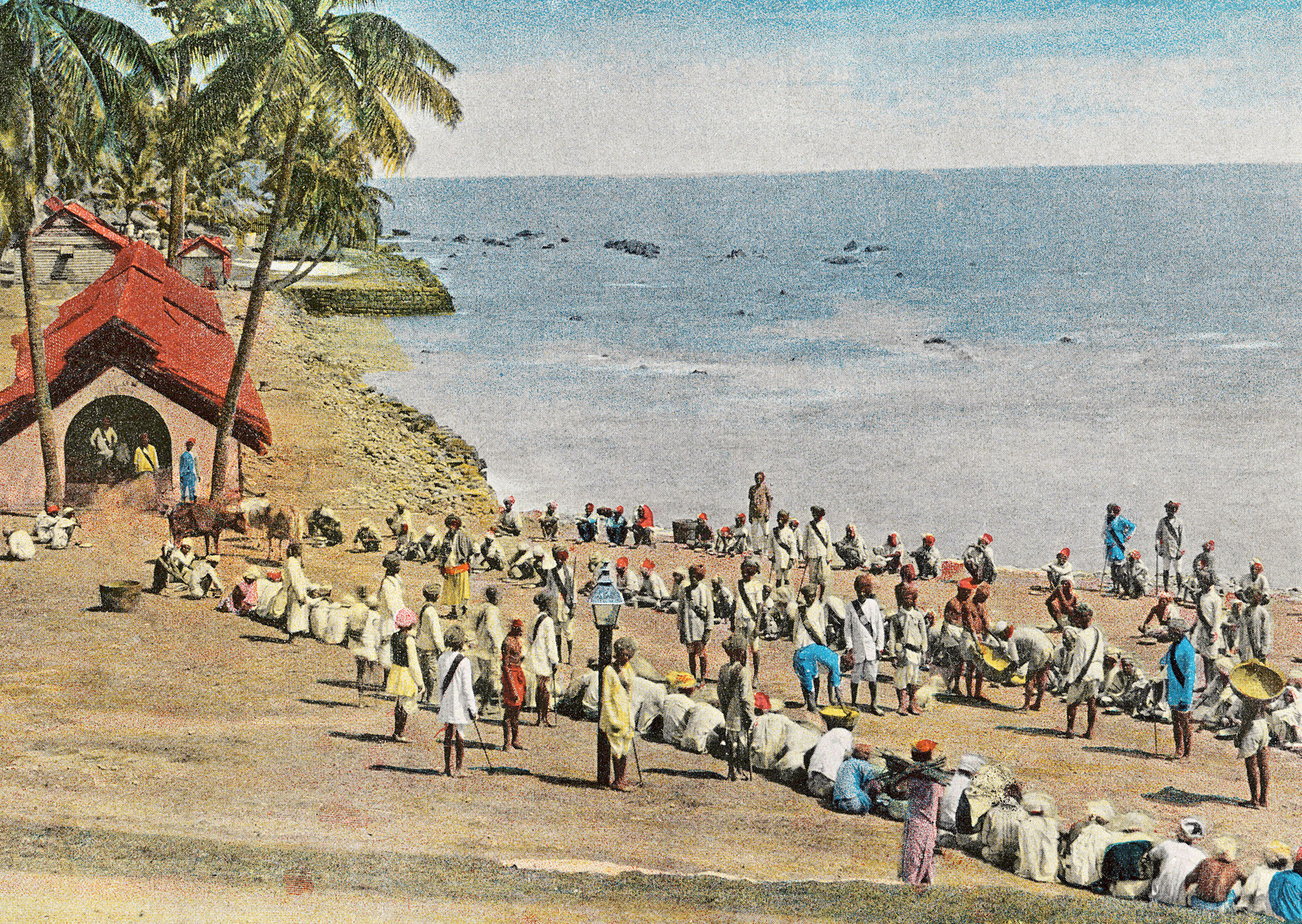

A penal colony was first established on Great Andaman Island in 1789. The British built a new prison after the Indian Mutiny to house their captives; here, prisoners take meals on the beach.

THE INDIAN MUTINY

Conan Doyle would have learned about the Indian Mutiny at school in the 1860s and 1870s, when the affair was fresh in British minds. It began in 1857, when sepoys—Indian soldiers—in the Bengal army shot British officers, escalating into full-scale rebellions across northern and central India. For months, garrisons such as Agra were beleaguered, until British authority was restored in 1858. Conan Doyle may well have gleaned details about Agra from Major-General Alfred Wilks Drayson, his sponsor at the Portsmouth Literary and Scientific Society. Drayson commanded the 21st Brigade Artillery in India from 1876–78, and helped rearm several forts, including Agra. Conan Doyle’s interpretation of the colonial mindset of the time, and how the rebellion revealed the true natures of those caught up in it, is fascinating. Small, Morstan, and Sholto alike are warped by their greed for the Agra treasure. Looting by British soldiers was common during the Mutiny, a subject Conan Doyle would revisit in “The Crooked Man”.

The villain’s character

The Sign of Four also has a more memorable, complex villain than the bland, one-dimensional Hope of A Study in Scarlet. With his wild eyes and wooden leg—the result of a crocodile attack—Small was largely inspired by Long John Silver in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1883). In Conan Doyle’s essay “Through the Magic Door” (1907), he wrote of Stevenson: “…he is the inventor of what may be called the mutilated villain,” and he “has used the effect so often, and with such telling results, that he may be said to have made it his own. To say nothing of Hyde… there is the horrid blind Pew, Black Dog with two fingers missing, Long John Silver with his one leg.”

Small wrestles with his conscience throughout The Sign of Four, which makes him a sympathetic character. What happens to him in the end is not clear. At worst he faces the gallows, the Victorians’ preferred method of execution, and at best “digging drains at Dartmoor,” as he puts it, presaging the looming presence of Princetown Prison in the later story The Hound of the Baskervilles.

"I never guess. It is a shocking habit—destructive to the logical faculty."

Sherlock Holmes

A police launch with “two burly police- inspectors” took Holmes, Watson, and Jones downriver in pursuit of the Aurora.

A classic tale

Two images in particular remain long in memory after reading this tale. First, the description of the victim at the murder scene—Bartholomew’s “ghastly, inscrutable smile,” and the way that “not only his features, but all his limbs were twisted and turned in the most fantastic fashion.” Second is Conan Doyle’s extraordinarily atmospheric, almost Dickensian, evocation of Victorian London. “Down the Strand the lamps were but misty splotches of diffused light, which threw a feeble circular glimmer upon the slimy pavement,” notes Watson in a particularly memorable passage. At the time, London was a thriving port, the hub of a great worldwide empire, and Conan Doyle’s busy riverside scenes are full of atmosphere. “Somewhere in the dark ooze at the bottom of the Thames lie the bones of that strange visitor to our shores,” says Watson, as he recalls Tonga’s dramatic demise.

Unlike A Study in Scarlet, this tale was widely reviewed on both sides of the Atlantic. London’s Morning Post commented rather pompously, “Mr. Conan Doyle has done better work… still, as a specimen of purely detective fiction, the tale has its merits.” The Daily Republican in Pennsylvania expressed a more general view when it stated, “…[Holmes’s] marvellous ingenuity in solving a seemingly insoluble mystery is portrayed with so graphic a pen that Conan Doyle must take rank as a leader in the line of such writers as Poe and Gaboriau. The Sign of Four is bound to become a classic.” However, by the time these reviews appeared, Conan Doyle had once again let Holmes slip from his mind, and was hard at work on one of his now long-forgotten historical romances.

Today The Sign of Four is indeed considered a classic. A 70-year-old Graham Greene wrote in the introduction to a 1974 edition of the book, “The Sign of Four… I read first at the age of ten and have never forgotten… the dark night in Pondicherry Lodge, Norwood, has never faded from my memory.”

The Thames was a hive of activity in the 19th century, its banks lined with ships, as can be seen in this painting of Tower Bridge from Cherry Garden Pier by Charles Edward Dixon (1872–1934).