IN CONTEXT

Short story

UK: July 1891

US: August 1891 (also as “Woman’s Wit” and “The King’s Sweetheart”)

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, 1892

Wilhelm Gottsreich Sigismond von Ormstein King of Bohemia.

Irene Adler American opera singer, and King Wilhelm’s former mistress.

Godfrey Norton British lawyer who marries Irene.

The first of the 56 Sherlock Holmes short stories to be published in The Strand Magazine, “A Scandal in Bohemia” is the tale that introduces the beautiful Irene Adler—the most talked-about minor character in the Holmes canon after Moriarty.

Even in the story, Irene appears directly only briefly, yet a world of scholarship and speculation has built up around her. Many screen adaptations have developed her in their own ways: in the US series Elementary, Moriarty is Irene Adler in disguise, and in the BBC’s series Sherlock, she is a high-class dominatrix who greets Holmes while naked.

Holmes and women

In the very first sentence of “A Scandal in Bohemia,” Watson tells the reader that “to Sherlock Holmes she [Irene Adler] is always the woman,” with “the” italicized to ensure the significance is clear. However, he then quickly stresses that “it was not that he [Holmes] felt any emotion akin to love for Irene Adler.” In fact, the whole idea of love is “abhorrent to his cold, precise but admirably balanced mind.”

And yet Conan Doyle has planted the irresistible hint that Holmes, emotionally cold and misogynistic, might have found his true love. It is a testament to Conan Doyle’s brilliant realization of his creation that readers wish so much for the apparently emotionless detective to find his mate. Watson implies that Holmes has rejected the love of women in order to keep his mind focused on the rational work of detection, turning himself into a noble and almost tragic figure. It is no wonder that some literary commentators have likened the detective’s behavior to that of the courtly knights of the Middle Ages, who desisted from sensuality in order to uphold their chivalric ideals. However, Holmes is a far more psychologically complex figure than any medieval hero.

"In his eyes she eclipses and predominates the whole of her sex."

Dr. Watson

Deep under cover in one of the convincing disguises he adopts when gathering evidence, Holmes (Jeremy Brett) finds himself accidentally caught up in Irene Adler’s wedding ceremony.

Holmes the bohemian

Since his marriage and move away from 221B Baker Street, Watson has seen little of his former companion. However, he is aware that Holmes spends a lot of time in his lodgings, interspersing bouts of work with regular drug binges—alternating weekly “between cocaine and ambition, the drowsiness of the drug, and the fierce energy of his own keen nature.” It seems that the detective needs a suitable outlet for his overactive brain when he is without a case to occupy his mind.

Although this story’s title ostensibly refers to a potential scandal for the King of Bohemia, the first mention of Bohemia is in relation to Holmes, when Watson tells the reader that the detective “loathed every form of society with his whole Bohemian soul.” The term “bohemian” was in vogue at the time, and referred to free-spirited individuals who led an unconventional lifestyle and rejected social norms. However, love and passion were also at the heart of the bohemian ideal—emotions that are anathema to Holmes. In calling this story “A Scandal in Bohemia,” Watson is perhaps hinting that the real scandal may lie not within King Wilhelm’s Bohemia but within Holmes, in a rare moment when a woman is able to capture both his respect and his admiration.

THE BOHEMIANS

Bohemia is a real place that was once a kingdom, but is now a region in the Czech Republic. However, “Bohemia” was also the imaginary spiritual home of the gypsy people, which is why, in the mid-19th century, the term “bohemian” came to refer to the unconventional, rootless lifestyle practiced by some artists, writers, and musicians. The bohemians were associated with romantic living—they were dedicated to artistic creation and free love—and some rejected material wealth. With their soft, colorful clothes and unkempt hair, they were easy to recognize. Some bohemians were political rebels, but for many it was just a way of life. Most were poor and lived in run-down neighborhoods such as Montmartre in Paris, Soho in London, and Telegraph Hill in San Francisco, but there were rich bohemians, too—those who rejected society’s values.

Bohemianism appeared in cities in Europe and the US in the mid-1800s, and reached its peak in the 1890s, when Conan Doyle wrote “A Scandal in Bohemia.”

Holmes at work

After his lengthy, slightly wistful introduction, Watson sets the story in motion. He is standing in the street below the Baker Street rooms. He looks up to the window and spots Holmes: “his tall, spare figure pass[ing] twice in a dark silhouette against the blind.” Holmes is remote and above the normal world, as he must inevitably be, but Watson can tell from his energetic pacing and alert posture that he is at work again: “He had risen out of his drug-created dreams and was hot upon the scent of some new problem.” Watson has already mentioned Holmes’s indulgence in narcotics, and he stresses it a second time in order to portray the great detective as a dramatic, romantic figure who switches between light and dark—his career illuminated as if by flashes of lightning in the night.

Eager to reconnect with his friend, Watson makes his way up to the rooms. Holmes is as cool and incisive as ever, noting several things with unnerving accuracy: the amount of weight Watson has gained since they last met; that he has gone back into practice as a doctor; that he has been out in the rain a lot recently; and that he has an incompetent serving girl. When Watson, astonished, asks how he does it, the detective explains his method by demonstrating that it all depends on observation. Watson sees things, he says, but he does not observe. Ordinary people fail to notice life’s minutiae, which is why Watson has no idea of the number of steps on the stairs up to 221B, but Holmes can tell him it is 17.

Such sharp observations are central to Holmes’s method, and today this is still considered the principal skill of a detective. However, as Holmes points out, a detective also needs to understand exactly what he is seeing, as he demonstrates when he goes on to show the doctor an anonymous note that he has just received. Watson can deduce only that the writer is wealthy, whereas Holmes can also reveal that he is a native German speaker (as only the German language would construct sentences with the verb falling at the end) and that the notepaper comes from the German kingdom of Bohemia. Furthermore, when his client arrives a few moments later, giving a false name and with his face hidden behind a mask, Holmes realizes immediately that this large, flamboyantly dressed man is in fact Wilhelm Gottsreich Sigismond von Ormstein—the King of Bohemia.

"A Frenchman or Russian could not have written that. It is the German who is so incourteous to his verbs."

Sherlock Holmes

The King and the diva

Holmes quickly makes his attitude toward royalty plain by adopting a curt, businesslike manner, aware that to anyone but the self-centered King, his disdain would be apparent. The King reveals that when he was Crown Prince he had a romantic liaison with a young American opera singer named Irene Adler, and was careless enough to have his photograph taken with her, thus leaving evidence of their affair. Recently, he has become engaged to a Scandinavian princess, and he is afraid that if her principled family were to be made aware of his past indiscretion, they will oppose the match. Irene has threatened to make the photograph public when the engagement is announced in a few days’ time, presumably, the King says, because she does not want him to marry another woman, and so he has been forced to seek Holmes’s help in locating and recovering the incriminating photo.

The King refers to Irene as a “well-known adventuress,” and many readers have taken his description of her at face value—the myth persists that she is a conniving blackmailer who uses her sexual wiles to make her way in the world. However, the King presents Irene in this way in order to justify his ill-treatment of her: he admits he has made several high-handed, even criminal, attempts to recover the photograph—including offering to pay for its return, hiring burglars to steal it, and even twice ransacking her home—all of which have failed.

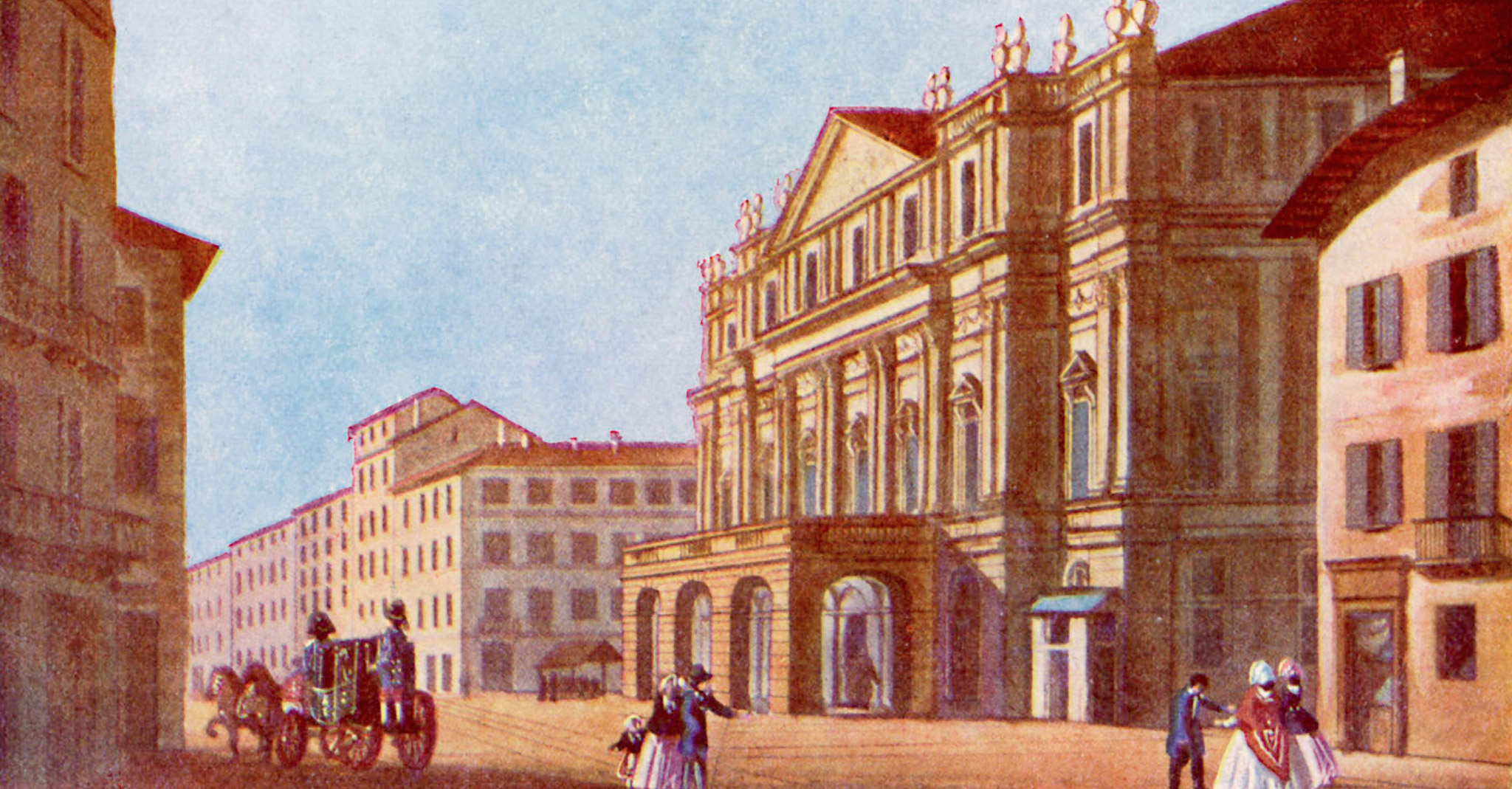

When Holmes consults his biographical card index, it reveals Irene Adler to be a retired opera singer who has sung at La Scala in Milan and was prima donna at the Warsaw Opera. To have reached those heights, she must have been a serious artist, rather than an amoral gold-digger. When the King admits Irene has not attempted to extort money from him, it is clear Holmes has already come to a different conclusion about Irene. Holmes yawns at the King’s arrogance, and can barely wait for him to leave. Uncharacteristically, he also discusses his fee—making the point that his only interest in this case is financial.

Disguise is an ongoing theme in this story, and despite Holmes’s usual mastery in the art of disguise, it is only Irene Adler who is completely successful in concealing her identity.

Holmes’s plan in action

The following afternoon, Holmes meets Watson after a morning’s investigation. He is amused and excited about the success of his efforts, and by the astonishing turn that events have taken. Disguised as a groom, he has been chatting with the men caring for the horses in a mews behind Irene’s house, and has learned a great deal about her.

The grooms, who would usually be first to spot anything salacious, described Irene respectfully as “the daintiest thing under a bonnet on this planet.” Indeed, she seems to live a normal, ordered life, and their only noteworthy observation is that she receives frequent visits from a handsome young lawyer named Godfrey Norton. Spotting Irene and Godfrey both leaving the house hurriedly in separate carriages, Holmes swiftly followed, only to find himself drafted in as witness to their legitimate and happy wedding in the Church of St. Monica in Edgware Road.

No wonder Holmes can barely contain his delight, especially as he has devised a “fool-proof plan” for recovering the photo, based on what he believes is his infallible knowledge of female psychology.

Later in the day, as per Holmes’s scheme, Watson is standing outside Irene’s house and watches the events that unfold: as Irene steps out of her carriage, a staged brawl between several men breaks out, and Holmes, this time disguised as a clergyman, comes to Irene’s rescue. However, he soon collapses to the ground with blood dripping down his face. Concerned for his welfare, Irene has him carried inside the house, to recover on the sitting room sofa. What Watson sees through the window is a lovely, kind young woman tenderly nursing the injured Holmes—not a femme fatale with a victim in her clutches. As he battles to decide what to do, Holmes gives him the pre-arranged signal to hurl a smoke bomb through the window and raise the alarm with a cry of “Fire!”

Just as Holmes has predicted, in the panic caused by the bomb Irene rushes to save the one thing that is most important to her—the photograph—and so reveals its hiding place in a recess behind a sliding panel. After confirming the fire was a false alarm, Holmes slips out of the house, intending to return the following day with the King to claim the picture. Holmes is so pleased with himself that he barely notices the young man who greets him cheerily in a strangely familiar voice as he and Watson arrive at the front door of 221B.

Holmes’s file on Irene Adler reveals that she was a talented contralto who once sang at the prestigious La Scala in Milan (pictured).

A surprise for Holmes

The next morning, when Holmes and Watson arrive at Irene’s home for their surprise visit, Holmes is amazed to find that the house-keeper has been expecting him—and to hear that Irene left for the Continent hours earlier, along with her new husband, taking the photograph with her. In its hiding place, she has left a letter to Holmes, and a photograph of herself in evening dress for the King.

Irene’s letter explains that she had realized the clergyman was Holmes in disguise the instant she betrayed the photograph’s hiding place—although she congratulates him on his performance. But to be certain that he was indeed the famous detective, she had dressed up as a youth and followed him home, and it was she who had greeted him outside his door.

One of the fascinating things about this episode is the way that it focuses on Holmes’s mastery of disguise—and yet Irene beats him at his own game. She tells Holmes that, as a trained actress, it is easy for her to wear “male costume,” and that she has dressed up as a youth on many occasions, in order to enjoy the freedom of being incognito. In fact, it may not have been so unusual for a woman to disguise herself in male clothes to pass in a man’s world. There is the renowned story of James Barry (born Margaret Ann Bulkley)—a woman who spent her entire life disguised as a man so she could pursue a career as a military doctor; likewise, there are many folk songs about women who joined the army in disguise.

The tradition of the undercover detective, though, goes back to the famous Eugène Vidocq (1775–1857), a French criminal-turned-detective in Napoleon’s time, whose amazing stories captivated 19th-century writers, such as Victor Hugo, Alexander Dumas, as well as Honoré de Balzac. They were surely an inspiration for Conan Doyle, too, together with the famous explorer Richard Burton (1821–1890), whose many exploits in disguise, such as sneaking into Mecca dressed as a Muslim, so intrigued Victorians.

"Male costume is nothing new to me. I often take advantage of the freedom which it gives."

Irene Adler

A worthy adversary

In “A Scandal in Bohemia,” Irene sees through Holmes’s disguise, despite his brilliance, and it is she who pulls the wool over his eyes. She escapes with her picture, and it seems that for her—as so often with Holmes—winning the game is enough. Now happily married, she declares in the letter that she has no interest in making the photo public, but will keep it as insurance should it ever be needed.

The King is certain that Irene will keep her word, and goes on to rue that she was not of his rank, as she would have made a great queen. “From what I have seen of the lady” Holmes responds coolly, “she seems indeed to be on a very different level to your Majesty.” It is clear that in Holmes’s opinion, she is far above him. The King offers Holmes an emerald ring as a reward for his work, but he asks instead to have Irene’s photograph. Some readers insist that Holmes’s choice shows he is in love with Irene. But he never mentions her again in the stories, except to acknowledge, as in “The Five Orange Pips”, that there was one woman who got the better of him. His regard for her is unmistakable, and the photograph is either simply for his files or a memento of a worthy adversary.

There is no doubt that Irene Adler is a fascinating character, and many feminist critics have commented on how she presents a challenge to the notion that reason, logic, and independent action are a male prerogative. American scholar Rosemary Jann believes that Irene “threatens male authority.” Yet Holmes, although shaken, does not seem threatened. Instead, he demonstrates perfectly his dictum that one should not be blinded by preconceptions. Irene has opened his eyes wonderfully.

In realizing his error, and being aware that a woman can easily take control of a situation without resorting to sexual power games or emotionalism, Conan Doyle’s Holmes seems far ahead of his time. More than a century on, it is a lesson that some adapters of this story have been slower to learn.

"…the best laid plans of Mr. Sherlock Holmes were beaten by a woman’s wit."

Dr. Watson

IRENE ADLER

Critics are divided in their analysis of Irene Adler (portrayed here by Lara Pulver). Some say she reflects the emergence of a new kind of young woman in the late 1800s: smart, self-confident, and assertive, a phenomenon some scholars now call “first wave” feminism. Not all would join the suffragettes’ campaign for votes for women, but these daughters of the middle class were beginning to believe in their right and ability to control their own lives. Increasingly, girls chose to go to the new women’s universities—significantly, Irene comes from America, where women’s education was further advanced than in Europe—and then to enter the workplace as teachers, doctors, and office clerks. However, others claim Irene represents a patriarchal Victorian view that only the most exceptional woman could match Holmes’s intellect on his own ground. After her brief triumph, she must slip back into the shadows of marriage. Still others view her as a male fantasy figure, giving men the salacious illusion of submission.