IN CONTEXT

Short story

UK: December 1892

US: January/February 1893

The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes, 1894

John Straker Racehorse trainer and retired jockey.

Fitzroy Simpson Wealthy London bookmaker and profligate gambler.

Colonel Ross Owner of the racehorse Silver Blaze.

Inspector Gregory Official investigating officer.

Silas Brown Trainer at Mapleton stables.

Ned Hunter Stable lad at King’s Pyland stables.

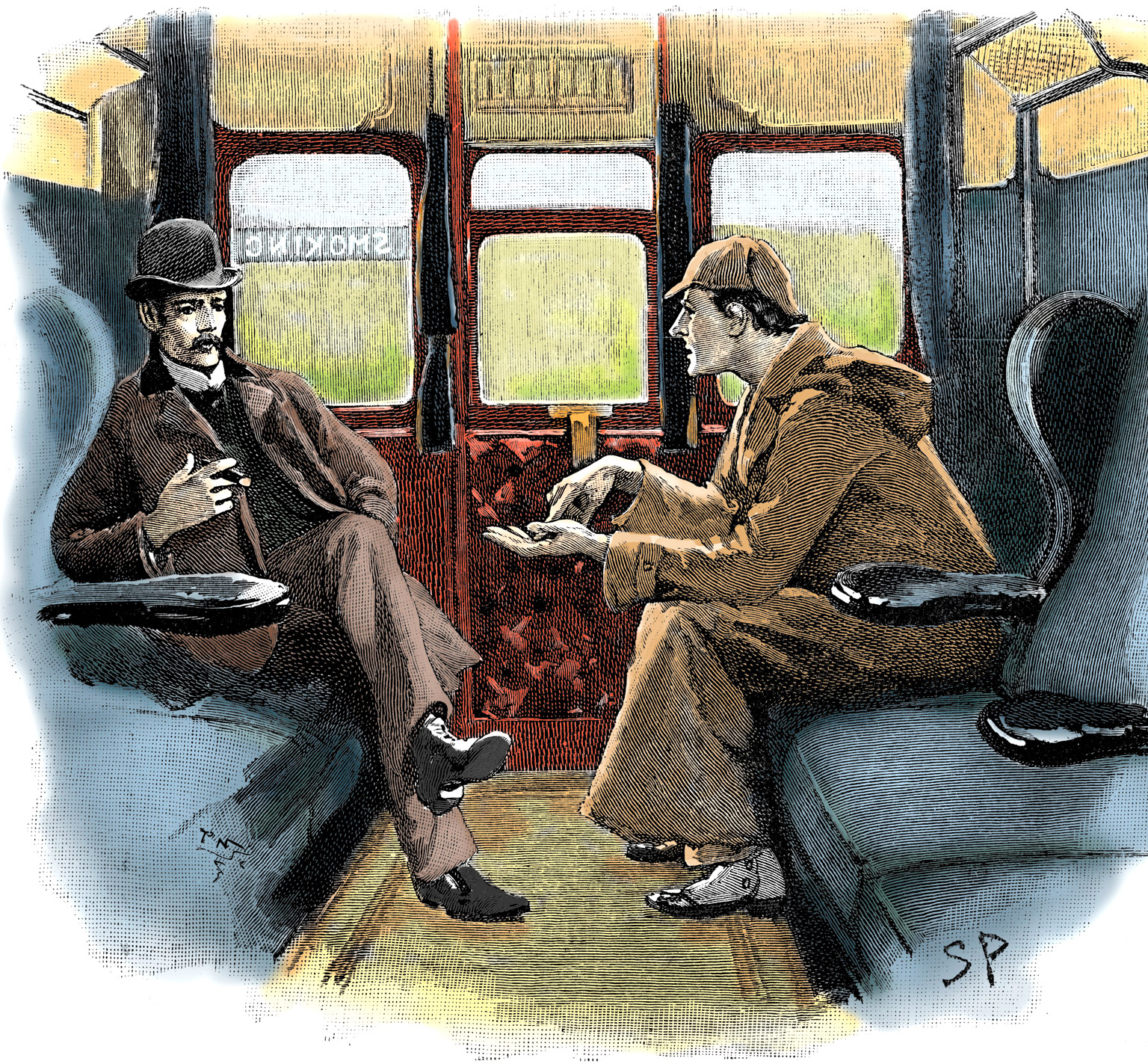

One of the most commonly reproduced images of Sherlock Holmes is a Sidney Paget illustration from “Silver Blaze,” showing a deerstalker-clad Holmes sitting in a train car. He is gesticulating with his long fingers as he expounds the mystery of a missing racehorse and its apparently murdered trainer to a cigar-toting Watson. Prior to this explanation, he (rather improbably) declares the train’s speed to be exactly 53½ miles an hour, based on the telegraph posts alongside the track being 60 yards apart. “Silver Blaze” is bookended by train journeys, during which both the exposition and the final explanation of the case take place.

A vanished favorite

The racehorse Silver Blaze, so named for his distinctive white forehead, has gone missing from his stable at King’s Pyland on Dartmoor, a week before he is due to run as odds-on favorite in the Wessex Cup. His trainer, John Straker, has been found dead out on the moor, his skull staved in and his hand gripped around a peculiar knife. Fitzroy Simpson, a bookmaker, is already in custody as prime suspect, having attempted to bribe his way into the stable on the evening in question. Furthermore, that same night he had dined at Straker’s house, where a portion of their curried mutton had been laced with opium and used to drug the stable boy who should have been guarding Silver Blaze. Simpson’s presence at dinner could have given him the opportunity to drug the food in order to later steal the horse. Simpson claims that in attempting to enter the stables he had merely been looking for some inside tips on the race, but his heavy palm-wood walking stick, a “Penang lawyer,” is a good fit for the murder weapon, and he seems entirely guilty of both the abduction and the killing—to everyone except Holmes, that is.

"…nothing clears up a case so much as stating it to another person."

Sherlock Holmes

Holmes is depicted here in his iconic deerstalker, in The Strand Magazine’s illustration from “Silver Blaze.” The watercolor version of this scene sold at Christie’s for $90,000 (£58,000) in 2014.

Dartmoor location

This case sees Holmes and Watson’s first encounter with Dartmoor, an evocative location to which they would return nine years later in The Hound of the Baskervilles. But whereas the Dartmoor of the later story is described as “forbidding,” “desolate,” and “melancholy”—a fitting setting for the chilling menace of the hound—here it is an invigorating place of unkempt beauty. As the two friends stroll across to the neighboring stables at Mapleton, Watson briefly describes how “the long sloping plain in front of us was tinged with gold, deepening into rich, ruddy brown where the fading ferns and brambles caught the evening light.” He bemoans only the fact that “the glories of the landscape were all wasted upon my companion,” although in fact even Holmes is not immune to its appeal, later thanking his hosts for “a charming little breath of your beautiful Dartmoor air.” In spite of this, the locals do seem to have an alarming propensity to set their dogs on strangers, and perhaps this is a subliminal hint of things to come.

An uncommon policeman

The investigating detective is Inspector Gregory, a policeman to whom Holmes is uncharacteristically complimentary, describing him as “an extremely competent officer.” Holmes is very impressed at the way Gregory has preserved the clues at the site of Straker’s apparent murder by instructing his men to stand on a piece of matting at the edge. This admiration for Gregory’s methods is in striking contrast to the ire Holmes expresses toward Lestrade when inspecting a crime scene in “The Boscombe Valley Mystery”: “Oh, how simple it would all have been had I been here before they came like a herd of buffalo and wallowed all over it.”

Gregory is consistently able to aid Holmes’s investigations—whether through appropriate snippets of information, a handy bag of boots, or a photograph produced from his pocket in timely fashion—which prompts the delighted detective to observe, “My dear Gregory, you anticipate all my wants.” Like another promising young inspector, Stanley Hopkins, who would not turn up at 221B Baker Street until more than a decade later, in “The Adventure of Black Peter”, Gregory makes great efforts to adopt Holmes’s own methods. And yet despite being a man who “was rapidly making his name in the English detective service,” the tall, leonine Gregory never appears again after “Silver Blaze.”

Facts that suit theories

Holmes’s one criticism of Gregory is his lack of imagination, and the value of this particular asset to an investigator is a point he returns to later on in the story. Yet this is a curious criticism for Holmes to make given that in “A Scandal in Bohemia”, he remarks that “It is a capital mistake to theorise before one has data.” In “Silver Blaze,” Holmes in fact advocates the exact opposite: he contrives a theory as to the missing horse’s whereabouts, then goes in search of proof. When he finally finds it, he crows, “See the value of imagination… We imagined what might have happened, acted upon the supposition, and find ourselves justified.”

The Epsom Derby was one of many popular races in Victorian England. The Wessex Cup in this story is fictional, yet the story has inspired several Silver Blaze Wessex Cup races globally.

Holmesian methods

Holmes employs a number of his stock deductive methods as he proceeds to unravel the crime at King’s Pyland. First, there is the sifting of information: he plows through all the accounts in the popular press in an effort “to detach the framework of fact—of absolute, undeniable fact—from the embellishments of theorists and reporters.” In doing this, he trims off the suppositions of others, leaving the reader with the impression that perhaps imagination is a grand thing—so long as it is Holmes’s own.

Once Holmes has arrived at the scene, there is the inevitable observation of small clues, in everything from the dead man’s effects to the environs of the stables and the murder scene. Various odds and ends of Holmes’s vast residual knowledge are here brought into play too, notably the fact of his being, as alleged in A Study in Scarlet, “well up in belladonna, opium, and poisons generally.” Most famously, there is Holmes’s last, tantalizing exchange with Inspector Gregory concerning the stable dog (see image), before he leaves Dartmoor.

A key clue for Holmes was the lack of noise made by the stable dog, which allowed the thief to lead Silver Blaze from the stable unheard. His deductions in this case gave rise to the phrase “the curious incident of the dog in the night-time,” later immortalized by Mark Haddon in his novel of the same name.

A flair for the dramatic

The matter of the stable dog’s silence as Silver Blaze was led out of his stall is one of several clues upon which the solution hangs, and soon Holmes has a firm handle on them all. The silent dog indicates its familiarity with the intruder; the curry used to mask the taste of opium and drug the stable boy in fact exonerates Simpson, as (being a guest) he could have had no hand in its preparation nor in its devising as a meal; and the “singular knife”—suited to surgical procedures—that was found on the dead man hints at a dark and specific purpose. It is well within Holmes’s power to resolve the matter before he leaves Dartmoor, but he chooses not to. Instead he assures Colonel Ross, the horse’s owner, that Silver Blaze will run in the Wessex Cup, and arranges to meet him at the Winchester Racecourse in four days.

Holmes justifies this delay as a playful form of retribution toward Ross, who has been dismissive of his abilities and somewhat prickly toward him: “The colonel’s manner has been just a trifle cavalier to me. I am inclined now to have a little amusement at his expense.” Whether we believe him entirely, of course, is a rather different matter, but Holmes is fond of a dramatic denouement and, as he remarks to a fellow detective in The Valley of Fear, “surely our profession… would be a drab and sordid one if we did not sometimes set the scene so as to glorify our results.”

Whatever Holmes’s motivation, the reappearance of the racehorse and the unmasking of the villain are beautifully staged. Silver Blaze turns out to have been both victim and killer, having fatally kicked his trainer in the head while the debt- ridden Straker attempted to rig the race by laming him with a “slight nick upon the tendons.” Since then, Silver Blaze has been hidden away at Mapleton, after being found wandering the moor by Silas Brown, Straker’s rival trainer, and subsequently disguised with dye to conceal his true coloring. Holmes neglects to reveal this fact to Ross, but as a bay-colored Silver Blaze dashes to victory at Winchester, the colonel is happy enough.

"I was marvelling in my own mind how I could possibly have overlooked so obvious a clue."

Sherlock Holmes

A vice revealed

At the races, Holmes cannot help indulging yet another vice: “But there goes the bell, and as I stand to win a little on this next race, I shall defer a lengthy explanation until a more fitting time.” His enthusiasm for the races is evidently shared by Watson who, in “The Adventure of Shoscombe Old Place’”, confesses that he spends half his pension on betting. It is, however, unlikely that Conan Doyle was an enthusiast himself. In his biography, Memories and Adventures, he acknowledges how his ignorance of horse racing “cries aloud to heaven” in “Silver Blaze,” which was at the time criticized by experts because had his characters really acted as he described, they would have either ended up in prison or been banned from the sport. “However,” Conan Doyle retorted, “I have never been nervous about details, and one must be masterful sometimes.”

VICTORIAN HORSE RACING

Horse racing was a hugely popular pastime in the Victorian era, one of the few events at which aristocrats and ordinary people met and mingled. Holmes has a shrewd understanding of the psychology of the betting man. In “The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle”, he tricks a wary poultry merchant into giving up information for a wager, observing that “when you see a man with …the ‘Pink ’un’ protruding out of his pocket, you can always draw him by a bet.” The “Pink ’un” was another name for The Sporting Times, one of several racing papers of the era. By the 20th century, however, the sport’s popularity had declined, and many of the smaller racecourses had disappeared, among them Winchester Racecourse at Worthy Down. In use since the 1600s, and patronized at one time by Charles II, its last race was run on July 13, 1887. By the end of World War I, it had been turned into an airfield.