IN CONTEXT

Short story

UK: June 1893

US: June 1893 (as “The Reigate Puzzle”)

The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes, 1894

Colonel Hayter Old Military friend of Watson’s.

Inspector Forrester Local police detective.

Old Mr. Cunningham Elderly local squire and justice of the peace.

Alec Cunningham Mr. Cunningham’s son.

Mr. Acton Neighbor in a land dispute with the Cunninghams.

William Kirwan Victim.

When it was originally published in The Strand Magazine in June 1893, Conan Doyle’s story about a landowning father and son was called “The Reigate Squire,” referring to the father, Old Mr. Cunningham, only. When it was included in The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes, however, it was retitled “The Reigate Squires,” to include the son as well. To complicate matters further, when published in the US in Harper’s Weekly (at the same time as the UK Strand publication) it was called simply “The Reigate Puzzle.” Interestingly, this was also the title used by Strand illustrator Sidney Paget in his account book in March 1893, so it may be that “The Reigate Puzzle” was in fact Conan Doyle’s original, working title.

Whatever title Conan Doyle preferred, the idea for the story came from “Health and Handwriting,” an article published in the Edinburgh Medical Journal in January 1890 and sent to him by its author, Alexander Cargill. He wrote to Cargill in 1893, saying, “I would like now to give Holmes a torn slip of a document, and see how far he could reconstruct both it and the writers of it. I think, thanks to you, I could make it effective.”

In 1927, Conan Doyle had to choose between this story, “The Adventure of the Bruce-Partington Plans,” “The Crooked Man,” “The Man with the Twisted Lip,” “The Gloria Scott,” “The Greek Interpreter,” and “The Resident Patient” for the final spot in his list of his 12 favorite Holmes stories (see Conan Doyle’s favorite stories). “I might as well draw the name out of a bag…” he wrote, “…they are all as good as I could make them.” But in the end he chose “The Reigate Squire,” on the basis that it was the story in which Holmes had shown the most ingenuity.

To prove that the earth is spheroid, Pierre-Louis Moreau de Maupertuis, the model for Conan Doyle’s villain, did experiments in Lapland in 1736.

The exhausted hero

The setup for the story is unusually dramatic, and lays the ground for the parochial crime that follows. Holmes has just broken a major international conspiracy. The villain of the piece was “the most accomplished swindler in Europe,” one Baron Maupertuis—named, with delicious irony on Conan Doyle’s part, after one of the greatest French scientists and adventurers. Pierre-Louis Moreau de Maupertuis (1698–1759) was the leading champion of Newtonian science in 18th-century France, and led an extraordinary expedition to the Arctic to prove Newton’s ideas about the shape of the world, during which he survived the winter conditions by sheltering in a tent.

Watson does not explain what Maupertuis’s evil namesake, the baron, has actually done, stating that his schemes are not “fitting subjects for this series of sketches.” However, it seems Holmes’s success in bringing him down was such a feat that all of Europe is “ringing” with the detective’s name, and his hotel room in Lyons is “ankle-deep with congratulatory telegrams.”

Holmes, though, was so utterly worn out by the struggle that Watson had to rush to his side and escort him back to 221B baher Street. Caring as ever, Watson has decided that they should take up the offer of a quiet stay in the Surrey countryside around Reigate, at the home of Colonel Hayter, “a fine old soldier” and Watson’s friend from his army days in Afghanistan.

And so, by the time they arrive at Colonel Hayter’s house, we have a complete picture of Holmes, the exhausted hero of international crime fighting, and of the dependable Watson. The shift from Lyons to Reigate also allows Holmes to solve a local murder rather than a grand crime, without being any less the great detective.

"I have usually found that there was method in his madness."

Dr. Watson

And so it begins

Their sojourn in Reigate has barely begun before news of a crime reaches Holmes’s ears. There has been a break-in at the nearby home of old Mr. Acton, during which some very odd things were stolen, including a ball of string. The very next morning they hear news of a murder at the “fine old Queen Anne house” of some other neighbors, old Mr. Cunningham and his son Alec: the Reigate squires. Moments later, Inspector Forrester—“a smart, keen-faced young fellow”—arrives. He has heard that Holmes is staying locally and is eager for him to help with the investigation. Watson tries in vain to persuade Holmes to stay out of it for the sake of his health. But, as Holmes teases him, “The Fates are against you, Watson.”

It is an intriguing case. The Cunninghams have both apparently witnessed a man wrestle with their coachman, William Kirwan, outside their house, shoot him dead in the struggle, then leap over the hedge and run away. The only clue is a scrap of paper found gripped in the dead coachman’s fingers, on which is written “at quarter to twelve learn what maybe.” This immediately sets Holmes’s mind racing, but he keeps his ideas to himself for now.

The deceptive letter that lured Kirwan to his death offers many clues to Holmes. Whoever wrote it was involved in the crime, and the time it occurred is clear. As Holmes observes, “Why was someone so anxious to get possession of it? Because it incriminated him.”

Meeting the squires

Holmes and the inspector head off to investigate the murder scene, where Holmes observes another clue that he keeps to himself. Holmes, Watson, the inspector, and Colonel Hayter then return to the Cunninghams’ house, where they are received by the father and son, the former elderly and with a “heavy-eyed face,” the latter a cheery, flashily dressed young man.

The two men inquire about the investigation, and Inspector Forrester is about to tell them about the scrap of paper when Holmes falls to the ground as if in a fit. Inside the house, however, he quickly recovers, and explains that he has recently been under a great deal of stress. He then composes an offer of a reward for information, but makes an uncharacteristic error when writing “at a quarter to one” instead of “at a quarter to twelve.” Old Mr. Cunningham happily corrects the text for him. Watson puts the apparent mistake down to Holmes’s illness, but Holmes has in fact, with his customary ingenuity, erred deliberately in order to get the old man to write down the very same phrase, “quarter to twelve,” so that he can compare his handwriting with that on the piece of evidence.

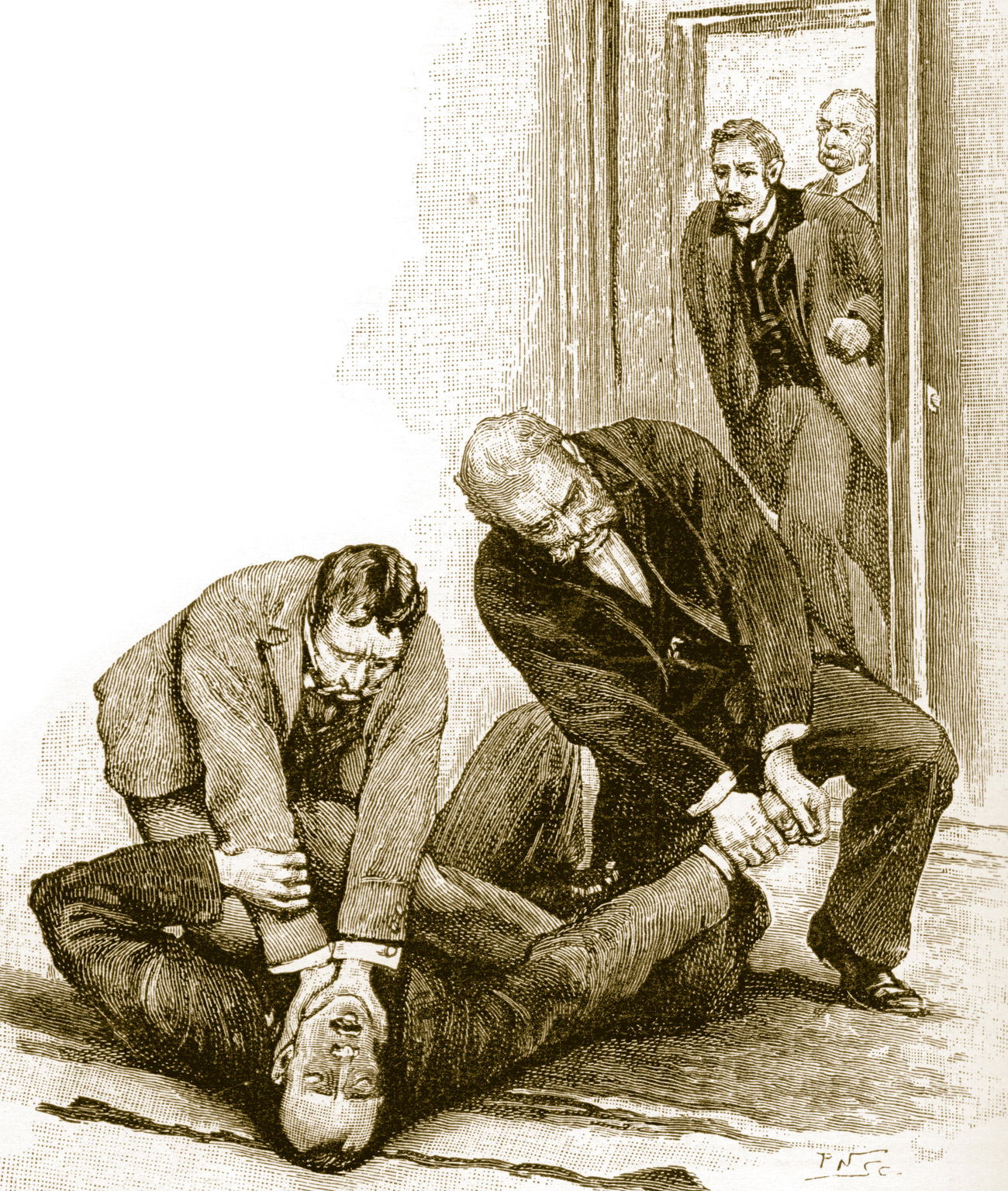

Holmes then asks if he might be shown around the Cunninghams’ home. When they are in old Mr. Cunningham’s bedroom, he hangs back with Watson, and, when no one else is looking, he deliberately knocks over a small table with a carafe of water and a dish of oranges on it, before loudly blaming Watson. As a confused Watson and the inspector stoop to clear up the mess, they hear a sudden cry of “Help! Help! Murder!” coming from Alec’s dressing room. Rushing in, they find Alec strangling Holmes, with his father trying to wrestle a piece of paper from Holmes’s grasp. Alec then tries to pull out a revolver, but within seconds both he and his father are under arrest. All that remains is for Holmes to explain how he solved the case.

In a rare physical attack, as drawn by Sidney Paget for The Strand Magazine, Holmes is overpowered and throttled by Alec Cunningham until Watson and Forrester rush to his aid.

Holmes tells all

Back at Colonel Hayter’s house, Holmes explains his methods. The key to solving the case was to concentrate on the scrap of paper, rather than allowing himself to be distracted by the Cunninghams’ witness statements. “It is of the highest importance in the art of detection,” he insists, “to be able to recognize, out of a number of facts, which are incidental and which vital.”

Someone, Holmes says, must have torn a piece of paper from the murdered coachman’s grip, leaving just the fragment found in his hand. If the murderer fled instantly, as the Cunninghams had said, it could not have been him. Could it therefore have been Alec, who was first on the scene?

Holmes explains how Forrester ignored this possibility because he assumed such respectable landowners could not be involved. “I make a point,” Holmes says, “of never having any prejudices, and of following docilely wherever fact may lead me.” This is a central plank in Holmes’s methods. He knows how easy it is to be blinded by preconceptions and so miss vital clues, which is why the police so often get it wrong. Even he must be vigilant to ensure he does not fall into the same trap.

The handwriting on the scrap of paper yielded key clues to Holmes’s sharp eyes. Holmes, it seems, is an expert in graphology: determining someone’s character from their handwriting. He explains how differences in the shape of the letters reveal that the writing was the work of two people. One has a stronger hand, and wrote parts of the message first, leaving the weaker hand to fill in the gaps. Holmes asserts that the stronger hand is that of the ringleader; that it is firmer and steadier also suggests that it was written by the younger of the pair. Similarities in the shaping of the letters also indicates that the writers are related. It must have been that Alec coerced his father into writing the note with him, so that they were equally responsible.

Holmes’s inferences are entirely plausible, but this is one instance in which Conan Doyle was wrong. Graphology has not turned out to be the exact forensic science that Holmes claims it to be, and it very rarely proves much help in criminal investigations. Experts can identify someone from their handwriting, even when that person tries to disguise it, but it is not possible to tell a person’s age, character, or gender from their handwriting.

"I tumbled down in a sort of fit and so changed the conversation."

Sherlock Holmes

GRAPHOLOGY

There was huge interest in the “scientific” study of personality in late Victorian times. Many people believed personality was revealed by physical traits, such as the pattern of bumps on the head—a now discredited idea called phrenology. Others believed in handwriting analysis, with some experts claiming that subtle differences in handwriting could reveal life stories. The theory originated with French priest Jean-Hippolyte Michon (1806–1881) and his followers, who, from 1830, established the “science” that came to be called graphology. In the same year that Conan Doyle wrote “The Reigate Squire,” French psychologist Alfred Binet (1857–1911, pictured) published a key text on the subject, which he considered to be “the science of the future.” Just a year later, graphology received a major blow when handwriting “experts” in France were exposed for their role in the conviction of Jewish artillery officer Alfred Dreyfus, wrongly accused of treason. Graphology never proved itself, and today it is considered a pseudoscience, like phrenology.

On closer inspection

An examination of the crime scene confirmed to Holmes that Alec’s witness statement was false on at least two counts. Firstly, the nature of the murdered man’s wound and the lack of powder-blackening around it showed Holmes, a pioneer in the science of ballistics, that the gun must have been fired from at least four yards away, and not at point-blank range. Secondly, there was no trace of any boot marks beyond the hedge that Alec claimed the murderer had leapt over. Alec, therefore, was lying, and must himself have been the murderer—in which case, he must also have torn the piece of paper from the dead man’s hand, and most likely thrust it into his dressing-gown pocket.

With the Cunninghams firmly in his sight, Holmes then sought a motive—and in the initial burglary he found one: the men were looking to destroy a document that proved Mr. Acton’s claim on half their land. When they could not find it, they took the strange items to make it seem like a burglary.

Land ownership was a hot issue at the time Conan Doyle was writing. In 1873, the UK government had commissioned “a second Domesday book” to record who owned each piece of land in the country. It was not only a huge work, but also political dynamite, since it revealed that just 4.5 percent of people owned all of the land in the UK, while 95.5 percent owned nothing. At the same time, 100,000 copies of American land reformer Henry George’s radical book Progress and Poverty were sold in the 1880s. In 1889, the Land Nationalization Society was formed to campaign for land to become the common property of all, and then in 1892 Alfred R Wallace wrote the best-selling Land Nationalization. Thus greedy, conniving landowners were very much in the spotlight.

Henry George (1839–1897) was an influential writer and politician who argued that the benefits derived from resources and opportunities belonged to all—not just wealthy landowners.

Diversionary tactics

With a motive established and strong evidence pointing to the two men, Holmes needed the piece of paper that had been torn from Kirwan’s hand. Once inside the Cunninghams’ house, Holmes had to create a diversion that would enable him to slip into Alec’s room and find the piece of paper—hence the reason he knocked over the table and pinned the blame on Watson. However, the Cunninghams followed him, and, seeing that he had found the note, they had become desperate.

Evidently, Kirwan had seen the Cunninghams in Mr. Acton’s house as they searched for the document, and had attempted to blackmail them as a result. The torn paper was a letter primarily designed to lure Kirwan to his death, but also cleverly worded in order to imply that he was guilty of the theft, thus staining his character too. The idea had been Alec’s—“a stroke of positive genius on his part,” says Holmes admiringly.

Having solved the crime, Holmes feels entirely rejuvenated. “Watson,” he says cheerfully, “I think our quiet rest in the country has been a distinct success, and I shall certainly return much invigorated to Baker Street tomorrow.”

Disputes of land ownership, such as that between the Cunninghams and Acton, were common in the 19th century, as ownership of land was based on voluntary registration.

ALEC CUNNINGHAM

Young, energetic, and full of life and cheeriness—Alec Cunningham seems to be the very opposite of how a murderer would be expected to look and behave. When Watson first encounters him, he describes Alec as “a dashing young fellow”; there seems nothing furtive or dangerous in him. But, as Holmes is quick to realize, looks can be deceptive; indeed, Alec is a perfect illustration of Holmes’s policy of the need to be wary of any kind of prejudice. Alec is not only involved in the murder but is also the leader who bullies his elderly father into going along with him. Alec’s bonhomie and fashionable clothes are a perfect mask for his brutal personality. He is perhaps the epitome of the rapacious English landowner with a sense of entitlement. His performance is so convincing that Inspector Forrester still thinks he is innocent even after seeing him try to strangle Holmes. Only when Alec pulls out his revolver does Forrester finally see the truth.