IN CONTEXT

Short story

UK: September 1904

US: December 1904

The Return of Sherlock Holmes, 1905

Stanley Hopkins Young police inspector.

Sir Eustace Brackenstall Wealthy man and owner of the Abbey Grange.

Lady Brackenstall (née Mary Fraser) Sir Eustace’s Australian wife.

Theresa Wright Lady Brackenstall’s maid.

Jack Croker Sailor and Lady Brackenstall’s admirer.

Frequently in the canon, Holmes’s sense of justice is at odds with legal convention—in “The Boscombe Valley Mystery”, for example, the detective sympathizes with the murderer because he was being blackmailed, and agrees to keep his crime a secret because he is an old man who is dying, and will soon have to answer “at a higher court than the Assizes.”

In “The Adventure of the Abbey Grange,” Holmes goes even further, allowing a healthy young killer to walk free. “Once or twice in my career,” he tells Watson, “I feel that I have done more real harm by my discovery of the criminal than ever he had done by his crime. I have learned caution now, and I had rather play tricks with the law of England than with my own conscience.” Watson, in turn, readily colludes with his friend’s morally dubious stance.

“The Abbey Grange” is notable, too, for tackling the dilemma of women trapped in abusive marriages: in this case with a husband who is a violent drunkard. Conan Doyle had had firsthand experience of alcoholism, for his own father, Charles, was a weak-willed alcoholic; he addresses the subject in several Holmes stories as well as in other works, including his short story “The Japanned Box.”

Like this grand house in Hampshire, Abbey Grange is a mansion built “in the fashion of Palladio.” Palladian design was popular in 18th-century Europe.

Holmes is summoned

“The Abbey Grange” begins early one bitterly cold winter morning in 1897. Holmes rouses Watson: they have been summoned by Inspector Hopkins to Abbey Grange—a Palladian mansion in Marsham, near Chislehurst, Kent—for what looks like a promising murder case.

On the train, Holmes indulges in some lighthearted criticism of Watson who, he claims, has a fatal habit of looking at everything with the eyes of a sensationalist storyteller, skating over the finer points. Watson’s grumpy riposte is that Holmes should try writing up his cases himself. Holmes assures his companion that he intends to do so in his old age. He claims that he will one day write a textbook that will “focus the whole art of detection into one volume.”

They are met at the doorway of Abbey Grange by Inspector Hopkins, who fills them in briefly on what has happened. The murder victim turns out to be Sir Eustace Brackenstall, “one of the richest men in Kent,” who is thought to have been killed when three burglars attacked him with a poker. Hopkins assumes from the descriptions given by Lady Brackenstall (and verified by her maid) that the attackers are the notorious Randall gang, who “did a job at Sydenham a fortnight ago,” rashly claiming that they did it “beyond all doubt.”

"A change had come over Holmes’s manner. He had lost his listless expression, and again I saw an alert light of interest in his keen, deep-set eyes."

Dr. Watson

The Brackenstall victims

Hopkins then introduces them to Lady Brackenstall—originally Mary Fraser from Adelaide, Australia. She is blonde, blue-eyed, and beautiful. “Seldom have I seen so graceful a figure, so womanly a presence, and so beautiful a face,” gushes Watson. She has a wound over one eye, along with two “vivid red spots” on one of her arms, which, she tells Holmes, have nothing to do with the events of the previous evening. However, the nature of these marks soon becomes clear when she explains that her husband of about a year was a “confirmed drunkard” who beat her up regularly and—we later learn—once doused her dog in gasoline and set it on fire. She has clearly been trapped in an abusive and desperately unhappy relationship.

She proceeds to tell her version of the events that occurred the previous evening. Around bedtime, on finding the dining-room window open, she was confronted by three burglars, who punched her in the eye and threw her to the ground, knocking her out. She awoke to find they had torn down the bell-rope, using it to tie her to a chair, and gagged her. Sir Eustace must have heard noises, as he burst into the room brandishing his “favourite blackthorn cudgel.” However, one of the burglars struck him down with a poker taken from the grate. He fell and never moved again. She passed out once more, and when she came to, saw that the men had picked up the silver from the sideboard. They were talking in whispers and each of them had a glass of wine in their hand, poured from a nearby bottle. When they finally left, she managed to free herself and raise the alarm.

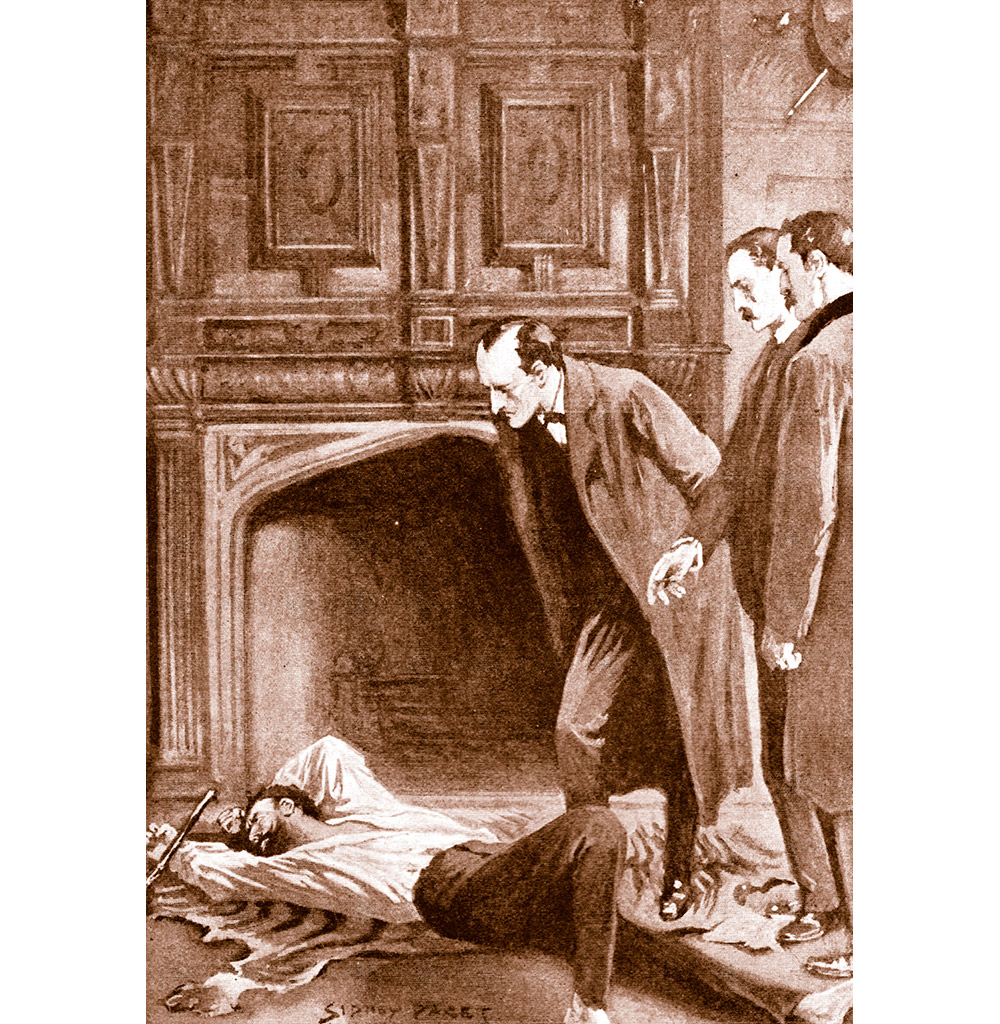

Murdered with a single blow from a fire poker, Sir Eustace Brackenstall—seen here in an illustration from The Strand Magazine—is not the helpless victim that he first appears.

Holmes has misgivings

The case seems to be clear-cut, and Holmes and Watson leave for London, and yet Holmes is plagued by doubts. Why would the Randall gang risk carrying out another burglary in the same area again so soon? Why murder Sir Eustace rather than simply overpower him, as the three of them could easily have done? Why steal so little? Why hit Lady Brackenstall to stop her screaming, as she would only scream more? And why did only one of the three wine glasses contain sediment? Holmes suspects that only two people drank the wine, but then poured the dregs into a third glass to give the impression three people had shared it. He decides to return and investigate further.

The three glasses of wine found near the victim are the most crucial evidence of all because they prove to Holmes that the crime scene has been faked. The presence of beeswing (sediment) in only one glass arouses his suspicions and leads him to conclude that only two people drank the wine.

Holmes investigates

Holmes locks himself in the dining room and, in the words of Watson, devotes himself “to one of those minute and laborious investigations” for which he is famous. Two hours later, he concludes that someone had not torn down the bell-rope, which would have rung the bell and alerted the servants, but instead climbed onto the mantelpiece and cut it cleanly with a knife. To do so, they had to be exceptionally tall—taller even than Holmes. And, from a bloodstain found on the chair where Lady Brackenstall was tied, he deduces that she was placed there after her husband’s death.

Establishing the truth

Lady Brackenstall has told a pack of lies, but after hearing from her austere but devoted maid Theresa the full extent of the abuse she has suffered at the hands of her husband, Holmes challenges her gently to tell him the truth. However, she maintains her story.

On leaving the Grange with Watson, Holmes stares at an unfrozen pond and scribbles a note for Hopkins, then suggests they visit the London shipping office of the Adelaide–Southampton line. From the real killer’s obvious agility, and the knots used to tie up Lady Brackenstall, Holmes has surmised that the culprit is a sailor, and most likely someone she met when she sailed to England. Sure enough, Holmes ascertains that one of the ship’s officers, Jack Croker, who lives in Sydenham, has not made the return passage. Hopkins, meanwhile, learns that the Randall gang has been arrested in New York, and therefore could not have committed the Abbey Grange “burglary.” Guided by Holmes’s note, he also finds the “stolen” silver at the bottom of the pond. Confused as to why the thieves had thrown away their haul, he does not take the hint when Holmes suggests it was put there “for a blind” to mislead people.

The case is resolved

Summoned by Holmes, Croker arrives at 221B Baker Street, where he is persuaded to tell the truth. “Be frank with me, and we may do some good. Play tricks with me, and I’ll crush you,” Holmes tells him.

Tall, handsome, blond, blue-eyed, and young, Croker stands for everything Sir Eustace did not: “as fine a specimen of manhood” as ever stood before them, reckons Watson. He is chivalrous, too, explaining that he fell in love with Lady Brackenstall on board the ship but, being a mere sailor, could only admire her from afar, and be happy for her when she later made a “favorable” marriage. However, a chance encounter with the maid Theresa revealed the horrible truth about Lady Brackenstall’s husband. He resolved to see her again and in due course she fell in love with him.

On the fateful night, the lovers were surprised by Sir Eustace, who rushed into the room, called his wife “the vilest name that a man could use to a woman,” and struck her with his cudgel. This is the crux of the story—the moment when Sir Eustace transgressed all moral boundaries. Croker grabbed the poker and struck him down, then gave Lady Brackenstall some wine to relieve her shock and had some himself. Croker and Theresa then acted swiftly to fake the scene. After dumping the silver in the pond to make it look as though a burglary had occurred, Croker departed, feeling he had done “a real good night’s work.”

Holmes plays judge

Satisfied with Croker’s account, Holmes sympathizes with his actions and says he will delay telling Hopkins for 24 hours so that he can flee. Croker is outraged, and swears that he would never dream of leaving Lady Brackenstall to be arrested as an accomplice. Delighted by this response, Holmes elects himself judge, and Watson jury. They duly pronounce him “not guilty,” and Holmes tells Croker to wait a year before claiming his beloved.

For Holmes, Captain Croker’s killing of a wife-beating tyrant is a case of justifiable homicide. His feelings of protectiveness toward Lady Brackenstall are reinforced by his admiration for Croker’s manly and unflinching loyalty. He has given Hopkins every chance to solve the case, and has insufficient faith that the law would acquit Croker. In this case, Holmes truly takes the law into his own hands.

"I should not sit here smoking with you if I thought that you were a common criminal, you may be sure of that. Be frank with me and we may do some good. Play tricks with me, and I’ll crush you."

Sherlock Holmes

INEQUALITY OF DIVORCE

It was once notoriously difficult for women in England to obtain a divorce, and Lady Brackenstall—trapped in a marriage to an abusive drunk—speaks with passion about the “monstrous laws” that prohibit her escape.

Before the mid-19th century, a full divorce was obtainable only through a Private Act of Parliament. In 1857, the Matrimonial Causes Act transferred divorce proceedings from Parliament to a civil court, but even then the grounds for divorce remained limited, and in practice it merely enshrined the double standard that existed between men and women. From 1857 to 1922, adultery was considered the sole ground for divorce. However, a husband’s adultery had to be accompanied by one or more other transgressions: incest, cruelty, bigamy, sodomy, or desertion. This did not apply to a husband who petitioned for divorce because of his wife’s adultery. Lady Brackenstall, therefore, confronted by great cruelty but evidently not adultery, was completely trapped.