Sherlock Holmes is the greatest fictional detective of all time; he is a man with exceptional powers of observation and reasoning, a master of disguise who is possessed of an uncanny ability to establish the truth. He is also an enigma.

The “emotional robot”

Initially, Holmes appears to be almost two-dimensional—a brilliant brain and human calculating machine with no personality or emotions. Even Conan Doyle said of him in an interview with The Bookman in 1892 that “Sherlock is utterly inhuman, no heart, but with a beautifully logical intellect.” And in “The Adventure of the Mazarin Stone” Holmes himself declares, “I am brain, Watson. The rest of me is a mere appendix.”

It may possibly have been Conan Doyle’s intention to create a cold, robotic character with no human feelings and the mind of a computer. If so, he did not succeed—and thank goodness, since such a character would not have been very interesting, let alone inspire the affection, and often adoration, that Holmes does. This public fondness is, to some extent, due to a natural inclination to fill in the blanks about him in one’s imagination—an innate tendency to believe that someone denying they have any feelings must be hiding a deep well of emotion. But it is also because of the undeniably deep affection Holmes inspires in others in the stories—Mrs. Hudson, Inspector Lestrade (eventually), and particularly Dr. John Watson. Watson may find Holmes’s vanity occasionally irritating, but his unstinting loyalty and indisputable fondness—so unmistakable that some commentators have, with no real evidence, suggested that he and Holmes are even lovers—reinforce the sense that Holmes is so much more than a brilliant robot. And every now and then, Holmes gives fleeting hints that the loyalty and fondness are returned.

Such is Holmes’s popularity that a blue plaque has been erected at 221B Baker Street. In Conan Doyle’s day, although Baker Street existed in real life, the house number 221 did not.

A complex interior

Conan Doyle also hints that there is a complex and deeply feeling character beneath the cool exterior. There is the drug use, which is an escape from boredom. There is the violin playing—so brilliant and yet so strange, which seems an outlet for emotions that cannot be expressed otherwise. And then there is the extraordinary river of compassion that runs through Holmes’s dealings with the many people, including villains, in his cases. On several occasions, Holmes lets a culprit go free once he feels that natural justice has been served, rather than subjecting them to the full letter of the “official” law. The picture Conan Doyle creates, and the one that makes Holmes so endlessly compelling, is the suggestion of hidden depths. He may be a person of extraordinary nobility who sacrifices his own feelings in order to serve the greater good by using his skills in detection. Or perhaps he is a man whose sense of inadequacy and interior pain lead him to bury his feelings and throw himself into his work. It is possible that both are true. In the BBC’s recent television series Sherlock, the detective’s difficulty with emotions is portrayed (by Benedict Cumberbatch) as a sign of mild autism.

Physical appearance

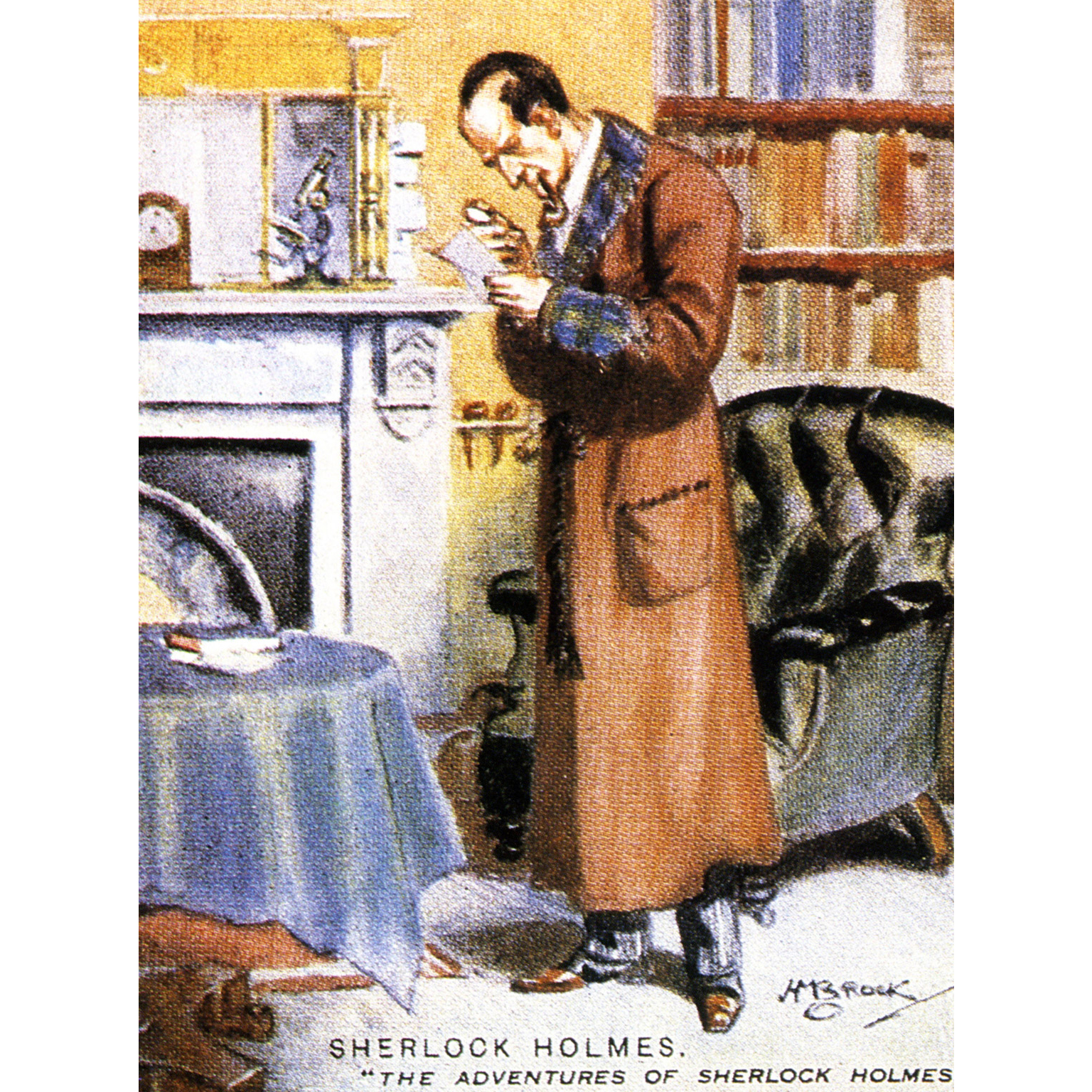

The one unambiguous thing about Holmes is his physical appearance, which was first brought to life by the Sidney Paget drawings in The Strand Magazine, which presumably Conan Doyle approved. In these, Holmes has sharp, angular features and is tall and thin, yet wiry and athletic, with reserves of strength that enable him to cope remarkably well in any physical tussle (aided by his knowledge of the martial art baritsu). Holmes’s tweedy attire, cape, and his now famous deerstalker hat—created by Paget in the drawings rather than by Conan Doyle—are as iconic as his trademark cane and pipe.

With his tall, gaunt frame, deep-set eyes, and aquiline nose, Sherlock Holmes is an instantly recognizable figure. Here, he features on a collectible cigarette card of the 1920s.

Holmes’s background

Conan Doyle gives away few details of Holmes’s life, adding to the enigma. “His Last Bow”, set in 1914, implies that Holmes is 60, meaning he was born in about 1854. His ancestors are “country squires”, and his grandmother the sister of the French artist Vernet—probably Charles Horace Vernet (1758–1836) as opposed to his father Claude Joseph (1714–1789). The only family member that the reader knows anything about is Holmes’s elder brother Mycroft.

Holmes claims that he developed his skills in deduction as an undergraduate. Commentators have, therefore, speculated where he went to university, the writer Dorothy L. Sayers theorizing that it was Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, while some scholars favour Oxford. There he had one true friend, Victor Trevor, who precipitated his involvement in “The Gloria Scott” case. He does not seem to have made any other friends since, except Watson. In “The Five Orange Pips” Watson suggests, “Some friend of yours, perhaps?” and Holmes replies, “Except yourself I have none.” His solitariness is lifelong.

In the 1870s, after university, Holmes moved to London and took up residence in Montague Street, near the British Museum. He had connections at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, which allowed him to conduct his experiments in the labs there, even though he was neither student nor staff. He was already developing his sideline as a consulting detective, but it was only after he met Watson in 1881 and moved into 221B with him as his co-lodger that the business became all-consuming.

Sidney Paget, the first illustrator of the Holmes stories in The Strand Magazine (some of which are shown here), was largely responsible for creating the popular image of Holmes.

Life with Watson

For eight years, Holmes and Watson were inseparable, and Watson was the witness and recorder of most of Holmes’s brilliant exploits as a detective—although some were kept from Watson. Then, in about 1889, Watson fell in love with Mary Morstan and moved away from 221B Baker Street to set up his own medical practice in west London.

The relationship between Watson and Holmes became more distant after Watson’s marriage, and we hear less of his cases—until the fateful one in “The Final Problem”, in which Holmes appeared to meet his death at Reichenbach Falls on May 4, 1891 in a struggle with the archvillain Moriarty. Years later, to the total amazement of Watson (and the reading public), he reappeared in London in “The Adventure of the Empty House”. His account of his missing three years, called the “Great Hiatus” by Holmes enthusiasts, was scant and involved hints of gripping adventures in Tibet, Persia, and Khartoum before he settled in Montpellier in southern France, where he conducted scientific experiments. The lack of information has led Holmes enthusiasts to speculate that he spent at least some of that time doing undercover work for the British government, via Mycroft.

By the time Holmes returned, Watson had been widowed, and they resumed their relationship, until Watson again moved out of 221B and Holmes retired to a cottage on the south coast near Eastbourne to indulge in the joys of the quiet life and his passion for beekeeping. But he could not entirely resist the urge to do a little detective work on his new home territory, as depicted in “The Adventure of the Lion’s Mane”, set in 1907, and later carried out vital work for the Foreign Office in the build-up to World War I in “His Last Bow.” After that, at age 60, Holmes finally vanished.

"I have chosen my own particular profession… I am the only one in the world."

Sherlock Holmes

Inspiration for Holmes

Although Holmes’s fame as a detective is unparalleled, he was by no means the first fictional sleuth. Edgar Allan Poe, Émile Gaboriau, and Wilkie Collins had all written about detectives, each of which can be seen, to some extent, in Holmes. From Poe, Conan Doyle drew upon the ideas of the “locked room mystery” and solving clues by clever deduction; from Gaboriau came forensic science and crime scene investigation; and from Collins something of Holmes’s appearance.

But when Conan Doyle was asked about his inspiration for Holmes, he didn’t mention any of these fictional figures. Instead, he referred to the real-life Dr. Joseph Bell—one of his former professors at Edinburgh University, who was renowned for his close observation and powers of deduction. Bell, too, had an interest in forensic science, and was often called as an expert for criminal trials. In 1892, Conan Doyle wrote to Bell, “It is most certainly to you that I owe Sherlock Holmes.” But Bell wrote back, “…you are yourself Sherlock Holmes and well you know it.”

MYCROFT HOLMES

Holmes’s elder brother Mycroft is a vibrant element in the Holmes canon—although, like Moriarty, he only appears directly in two stories. The reader is never told anything about his early life, except that he is seven years older than Sherlock Holmes, and, if anything, even cleverer. “He has the tidiest and most orderly brain,” says Sherlock, “with the greatest capacity for storing facts, of any man living”. His brilliance has given him a place at the heart of the secret government machinery in Whitehall, and he is a crucial source of intelligence. As Watson remarks, Mycroft is “the most indispensable man in the country”—“Again and again, his word has decided national policy.” Mycroft is considered by some critics to be the head of the secret service, although this is never specified.

The real-life inspiration for Mycroft Holmes may well have been Robert Anderson, whose role in government (as head of the secret service and the CID, and a key adviser on government policy in the 1890s) closely corresponds to that of Mycroft in the stories.