The combined magic of Conan Doyle’s compelling fictional creation, and the evocative pictures by Sidney Paget that illustrated his adventures, have long made the detective-hero and his army-doctor companion a gift for dramatic portrayals. For well over 100 years, Sherlock Holmes has been a fixture of popular culture, starring in hundreds of plays, movies, and television shows, and even a Russian ballet.

These numerous appearances across a variety of different media have enhanced Sherlock Holmes’s legendary status. Different aspects of his iconic character have been explored in each new adaptation and interpretation of his famous adventures. On stage and screen, the subsidiary characters that populate the stories, such as Mrs. Hudson, Professor Moriarty, Irene Adler, and Inspector Lestrade, have also become more prominent, adding even more detail and color to Holmes’s unique world.

Curtain up

Conan Doyle had made several unsuccessful attempts to write for the stage when, in the 1890s, he created a five-act play featuring Sherlock Holmes. Charles Frohman, a US theater producer, expressed an interest in the work, but was unimpressed on reading it. He persuaded the author that the US actor and playwright William Gillette would be the ideal person to rewrite the script and take the lead role. Conan Doyle, happy to relinquish the project, agreed. Initially his only restriction was that Holmes should not fall in love; however, he was soon persuaded otherwise, writing to Gillette, “You may marry him, murder him, or do whatever you like to him.”

The play—the plot of which was drawn largely from “A Scandal in Bohemia” and “The Final Problem”—opened in New York in 1899. The critics sneered, but the public cheered, and William Gillette toured intermittently with the play for the rest of his life. He also appeared in a film adaptation in 1916, which was feared lost for many years, until, remarkably, a print of it was discovered in France in 2014. Conan Doyle did go on to write two plays that were performed on the London stage: a three-act version of “The Speckled Band” in 1910, and The Crown Diamond—a one-act drama later adapted as the short story “The Mazarin Stone”.

"He has that rare quality which can be described as glamour… His impersonation of Holmes amazes me."

Arthur Conan Doyle

on Eille Norwood’s performance

The Sign of Four (1923) was the final film in the Sherlock Holmes series made by Stoll Pictures. Conan Doyle enjoyed Eille Norwood’s “masterly” portrayal of Holmes.

Lights, Camera, Sherlock

To begin with, the film industry relied heavily on literary sources for material, and it was little surprise that the popular Sherlock Holmes stories became a recurring source of inspiration for silent movies. Indeed, between 1910 and 1920 more than 50 films were made featuring Holmes. These fell into one of two camps: either they attempted, with varying degrees of success, to be true to the plots and characters of the stories, or they simply took the detective’s basic characteristics and put him in new—and sometimes inappropriate—scenarios, and ignored most of his unique traits.

In the 1922 Goldwyn Pictures movie Sherlock Holmes, based on William Gillette’s successful play, matinee idol John Barrymore played Holmes as a youthful, handsome, tousled-haired fellow. By contrast, Professor Moriarty was portrayed as a grotesque figure by German actor Gustav von Seyffertitz; so eerie and powerful was von Seyffertitz’s performance that when the film was first released in Britain, its title was changed to Moriarty.

The British actor Eille Norwood is widely regarded as the greatest Holmes of the silent movie era—and the first actor to successfully embody the character beyond the pages of The Strand Magazine. He starred in 47 titles in two years for the Stoll film company, and while not possessing the gaunt, aquiline, Paget-like features, he was a convincing Holmes. He even went as far as shaving his hairline to create the impression of Holmes’s extra “frontal development.”

Premiering at Broadway in 1899, the Gillette-authored Sherlock Holmes was a big success, touring the US and the UK. It was also revived several times.

Holmes talks!

Conan Doyle did not live to see the first Sherlock Holmes film to feature sound—The Hound of the Baskervilles, produced in the UK by Gainsborough Pictures in 1930—but this is perhaps just as well, since the film was not a success. During the rest of the 1930s, the performer who received the critics’ thumbs-up for presenting “the perfect Holmes” was Londoner, Arthur Wontner. He starred in five features and faced Moriarty in two of them: The Triumph of Sherlock Holmes (1935) and Silver Blaze (1937).

Top billing

It is interesting to note that all the Holmes films up until the late 1930s were set in the period in which they were made, instead of in the Victorian or early Edwardian era of the original stories. Also, the actor playing Watson was always set well down the cast list, far away from Holmes’s star billing. All this was to change in 1939. In March, US film company Twentieth Century Fox released The Hound of the Baskervilles, featuring British actors Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce as Holmes and Watson, and set in the late Victorian period. Nigel Bruce received fourth billing and even Rathbone only second—below the romantic lead. The film was a surprise hit, and just months later Fox released a sequel, The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, featuring the same actors. This time, the doctor was given equal, top billing with his Holmes.

Filmmakers had long grappled with the problem of Watson’s role. In the stories, he is the narrator of the events, which is difficult to emulate on screen. Twentieth Century Fox found a solution to this—they transformed him into a bumbling, comic character, raising his cinematic profile in the process. Meanwhile, with his charismatic screen presence and strong resemblance to the detective of Paget’s illustrations, Basil Rathbone became the most authentic Holmes to that generation of moviegoers; his performance set the benchmark for the silver-screen portrayals that followed.

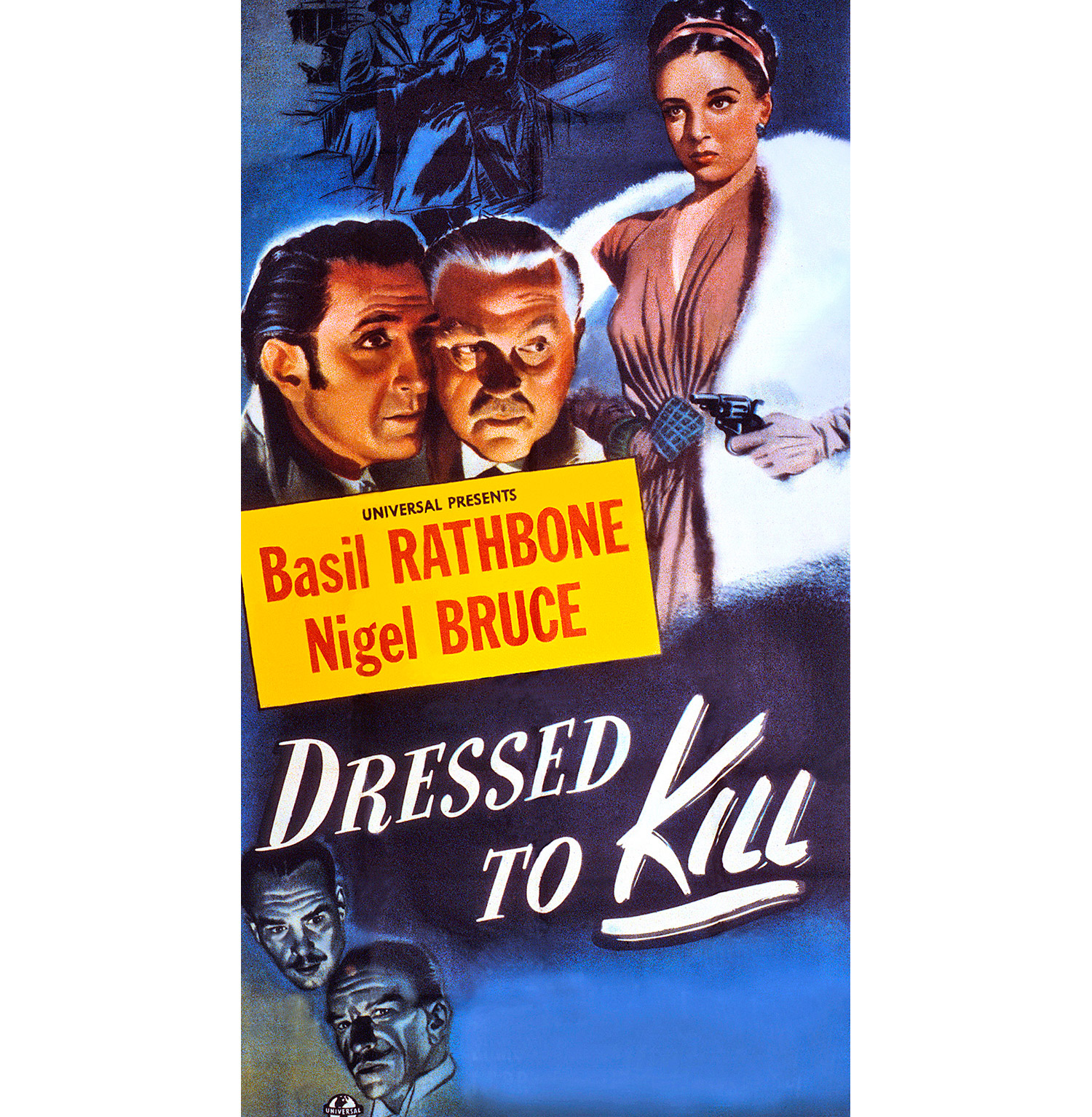

These two movies marked the beginning of a long run as Holmes and Watson for Rathbone and Bruce, and very shortly afterward they became involved in a highly successful, long-running radio show, The New Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. Fox no longer cared to finance further expensive, Victorian-themed films, and in 1942 Universal Pictures began a series of B movies starring Rathbone and Bruce as the Baker Street duo, transporting them to modern-day London. The first three Universal movies used the ongoing World War II as a backdrop, and Holmes found himself fighting the Germans and unmasking Nazi spies. This removal of the detective from his usual milieu had the effect of cutting him free from Conan Doyle’s influence, thereby helping to promote him as an independent character. However, Rathbone grew tired of playing the role, and in 1946, after a total of 14 outings, he decided to bring his Holmes film career to an end. In the 1950s he appeared briefly as Holmes on television and in an unsuccessful Broadway play.

Dressed to Kill (1946) was the fourteenth and final movie starring Rathbone and Bruce as Holmes and Watson. Its plot was based on “The Adventure of the Dancing Men.”

"Watson insists that I am the dramatist in real life… Some touch of the artist wells up within me, and calls insistently for a well staged performance."

Sherlock Holmes

The Valley of Fear (1915)

The horror Holmes

After the international success of their technicolor treatments of Frankenstein and Dracula in the mid-1950s, the British company Hammer Films next turned their attention to Conan Doyle’s chiller, The Hound of the Baskervilles. Horror-movie stalwart Peter Cushing took the lead—and was slightly alarmed to learn that producer James Carreras had presold his incarnation of the great detective as a “sexy Sherlock.” Watson was played by another Hammer regular, André Morell, whose intention to portray him as “a real person and not just a butt for Holmes” resulted in a realistic and solid cinematic portrayal of the doctor.

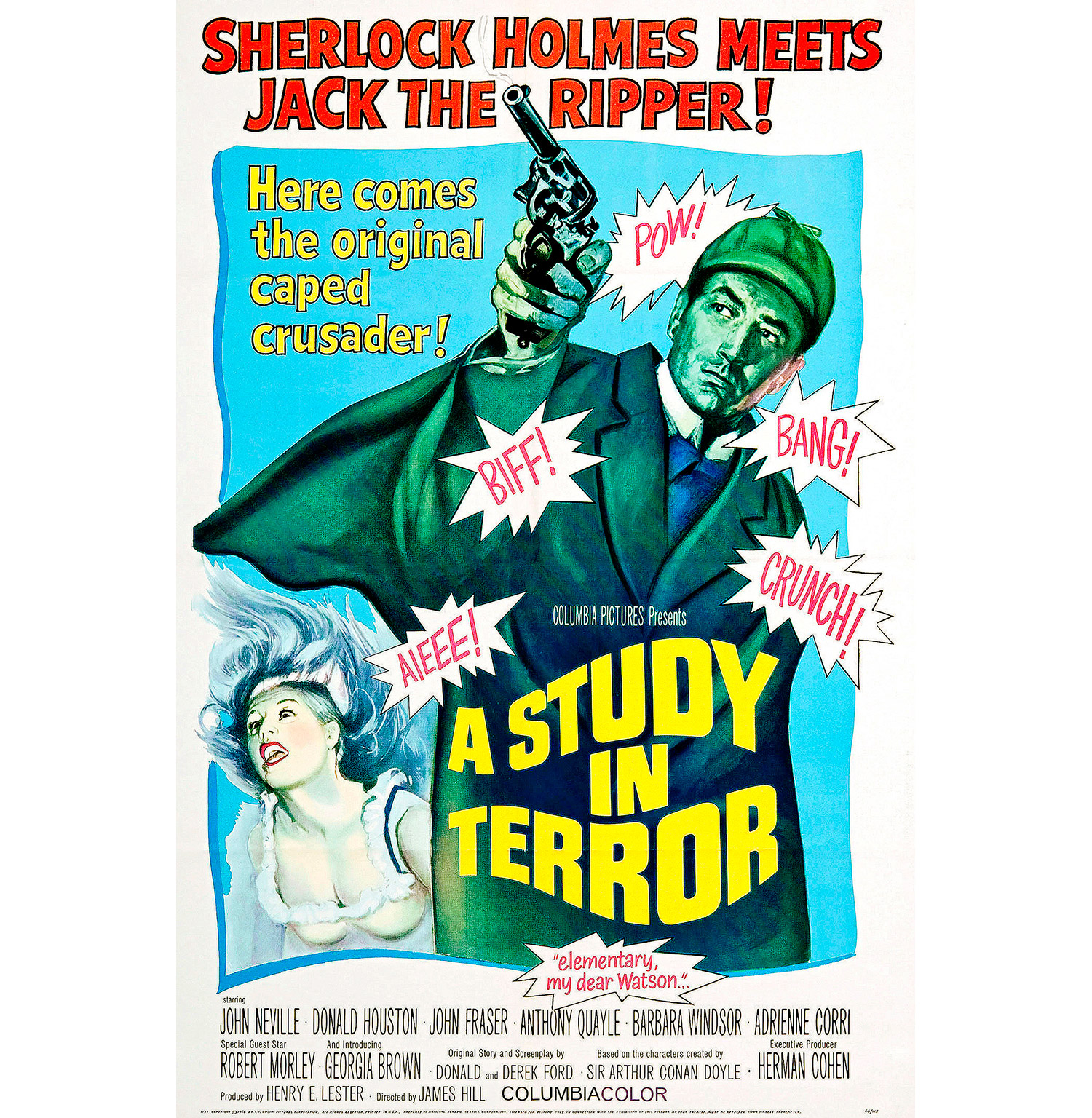

Sir Nigel Films, a British company formed by the Sir Arthur Conan Doyle Estate to film the author’s works, was the force behind another “horror Holmes”: 1965’s A Study in Terror. The movie’s storyline pitted the world’s greatest detective against its most vicious killer, Jack the Ripper. In a bid to capture the youth market, and cash in on the success of the Batman TV series that was very popular at the time, Holmes was billed as “Sherlock Holmes—the Original Caped Crusader.”

Holmes faced Jack the Ripper again in 1979, in the superior British- Canadian Murder by Decree, with long-established Hollywood actors Christopher Plummer as Holmes and James Mason as Watson. The pair formed a warm relationship, displaying a more human side to the characters for the first time.

In this gory Sherlock Holmes comic-book horror, released in 1965, the detective pits his wits against the real-life notorious Victorian serial killer, Jack the Ripper.

Holmes on the small screen

Sherlock Holmes’s television career took off in the early 1950s, with productions in both the UK and US. The first was a BBC six-part series (shown live, so no tapes exist). Sherlock Holmes, a 39-episode series made for the US market, was shot on a shoestring budget in France and broadcast in 1954. Wanting to appeal to younger viewers, its producer cast fresh-faced English actor Ronald Howard as Holmes; he gave a lively and appealing performance. His Watson, character actor Howard Marion Crawford, played the part in a buffoonish way.

In 1964, Douglas Wilmer donned the deerstalker in a second BBC series that kicked off with The Speckled Band and was followed by a further 12 stories the next year. His performance was closely modeled on that of Basil Rathbone, and was praised for its faithfulness to the original stories. However, Wilmer was unhappy with the scripts (sometimes even rewriting them himself) and the production values, and refused a second series.

In 1968, Peter Cushing stepped into Wilmer’s shoes for a two-part adaptation of The Hound of the Baskervilles, which remains one of the most faithful versions of the story. However, once the rest of the 16-episode series—the first to be made in color—got under way, Cushing experienced similar problems to those encountered by Wilmer. But the actor’s devotion to the character and attention to detail were unfailing: he requested that his costumes replicate those shown in the Paget illustrations, thus exploding the myth of the great detective’s Inverness cape: “It’s not an Inverness cape… it’s a long overcoat with a hood.”

"The stage lost a fine actor, even as science lost an acute reasoner, when [Holmes] became a specialist in crime."

Dr. Watson

“A Scandal in Bohemia”

Holmes on the radio

When Basil Rathbone gave up playing Holmes on screen, he also left the US radio series, but Nigel Bruce continued to play Watson with other Sherlocks. In Britain, the great detective was a comparative latecomer to radio, and it was not until the 1950s that he was granted a series. The pairing of two distinguished actors, Carleton Hobbs as Holmes, with his high, reedy, alien tones, and Norman Shelley as Watson, with his dark plum pudding of a voice, proved successful, and they inhabited the parts intermittently from 1953 to 1969. Today, the duo sound decidedly middle-aged, but they were very popular at the time.

Perhaps the most illustrious of all radio Holmes and Watsons were Sir John Gielgud and Sir Ralph Richardson—two of Britain’s greatest Shakespearean actors—who appeared on the BBC in 1954 in a short series.

In 1988, the BBC decided to adapt all of Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes tales for radio, including the novels, and within 10 years the whole canon had been recorded and broadcast.

Peter Cushing’s Holmes with Bishop Frankland (Mr. Frankland in the novel) in a scene from Hammer Film’s 1959 adaptation of The Hound of the Baskervilles.

Off-the-wall portrayals

Between the Peter Cushing television series of the late 1960s and the emergence of Jeremy Brett in the 1980s in one of the most notable of all depictions, there were a number of unusual Holmes portrayals. Perhaps the most refined of these was Robert Stephens in Billy Wilder’s The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (1970), an almost effeminate incarnation, with languid movements, a nasal drawl, and wavy hair. Mark Gatiss, the co-creator of the BBC’s successful Sherlock television series, has said that the movie was “a template of sorts for Steven Moffat and me as we made our adaptation.” James Bond star Roger Moore later presented a Simon Templar-like version in Sherlock Holmes in New York (1976); while acting heavyweight George C. Scott played a New York lawyer who thinks, and indeed acts, like the great detective in the bleak comedy They Might Be Giants (1971), featuring the first female Watson, Joanne Woodward. The mercurial Scottish-born stage actor Nicol Williamson was a neurotic and emotionally disturbed Holmes in 1976’s The Seven-Per-Cent Solution, which saw Holmes being treated by Sigmund Freud for cocaine-induced psychosis.

In 1985, Spielberg’s Young Sherlock Holmes billed itself as an “affectionate speculation” that addressed the question of what might have happened had Holmes and Watson first met at a boarding school. The ensuing mystery also introduces the young Moriarty and Inspector Lestrade. Holmes matures over the course of the action, acquiring a curly pipe and a deerstalker hat, and his doomed romance cleverly hints at why, in later life, he adopts a distant attitude toward women.

"The definitive Sherlock Holmes is really in everyone’s head. No actor can fit into that category because every reader has his own ideal."

Jeremy Brett

TV Times interview (1991)

Holmes around the world

In the 1930s, the German film industry produced a number of Holmes movies, essentially adopting the character for use in a series of wild adventure films. The 1937 De Hund Von Baskerville, featuring a gun-toting Sherlock Holmes in a leather overcoat and flat cap, was a favorite of Adolf Hitler: in 1945, a copy of the movie was found in the Führer’s private collection in the Berghof, his mountain residence. In 1967, Germany produced a television series based on the scripts for the BBC’s Douglas Wilmer series, with stage actor Erich Schellow as a rather down-at-heel, drug-addicted version of the Baker Street sleuth.

Between 1979 and 1986, Soviet television screened a series of Sherlock Holmes films, split into 11 episodes. In 1986, a movie adaptation, The Twentieth Century Approaches, was made from the last four episodes. Produced by Lenfilm, the series featured Russian actors Vassily Livanov as Holmes and Vitaly Salomin as Watson; they were chosen for the “Englishness” of their appearance and for their likeness to the Paget drawings. The adaptations themselves remained very close to the original Conan Doyle plots, but tended to include a great deal of humor.

In Sherlock Holmes, Conan Doyle created a template that can be used in almost any art form or genre. Arguably, no other fictional character is so adaptable. The enduring flexibility of Holmes is itself a subject of study.

ANIMATED APPEARANCES

Some of the most eccentric depictions of Holmes have been made for children—in the form of cartoons. As early as 1946, Daffy Duck met the detective in “The Great Piggy Bank Robbery.” In 1986, Disney produced Basil, the Great Mouse Detective, who, along with his friend Dr. David Q. Dawson, lived beyond the baseboards at 221B Baker Street. Professor Rattigan, their Moriarty-like adversary, was voiced by Vincent Price.

In the 1980s, Holmes’s ghost appeared in an episode of Scooby Doo, while in “Elementary, My Dear Turtle,” the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles enlisted Holmes’s help in thwarting Moriarty’s bid for world domination. In the 1999 US television series Sherlock Holmes in the 22nd Century, the detective was revived by a biologist to combat a clone of Moriarty; in order to assist him, Inspector Lestrade’s “compudroid” read Watson’s journals and assumed the doctor’s name, face, voice, and mannerisms. And in 2010, Holmes met Tom and Jerry in a full-length movie.

A definitive portrait?

During the 1980s and early 1990s, British actor Jeremy Brett gave what many consider to be the defining Holmes performance, in a series made by Granada Television. The intention was to create a truly authentic Holmes, and no actor before Brett had managed to embody so many of the attributes created by Conan Doyle. As Michael Cox, the series’ producer, observed, Brett “had the voice, the actor’s intelligence, the presence, the physique, the ability to jump over furniture, be convincing in a disguise, handle the horses, and whatever else that may be required.”

For millions of fans all around the world, Brett was Holmes. In his mesmerizing performance, the controlled eccentricities, the mannered delivery, and the furious outbursts combined to create an enduring portrayal of the great detective. Brett was partnered by two excellent but contrasting Watsons: David Burke, who gave a sensitive and at times jovial performance, and then Edward Hardwicke, who inhabited the role for eight years, combining a strong sense of loyalty and tolerance with quiet authority.

"I think people fall in love, not with Sherlock Holmes or with Dr. Watson, but with their friendship."

Steven Moffat

Co-writer of BBC’s Sherlock

Jeremy Brett portrayed Holmes in the 1984–1994 Granada Television series. The actor admitted that the role was “the hardest part I have ever played.”

Holmes in the 21st century

In the 21st century, the world’s fascination with the super sleuth of Baker Street is as strong as ever. In 2009 and 2011, two movies by British director Guy Ritchie presented an exaggerated, cartoonish, action-hero version of the great detective—played with anarchic relish by Robert Downey Jr.—with all his foibles and habits magnified or lampooned.

Meanwhile, on the small screen, two recent ventures have created a thoroughly modern reimagining of the detective and his world. In Elementary, which had its US premier in 2012, Sherlock Holmes (played by British actor Jonny Lee Miller) is a recovering drug addict who helps the New York City Police Department solve crimes. His female Watson (Lucy Liu) is a former surgeon who is initially appointed as his sober companion (to prevent him from relapsing), but becomes a pupil of sorts when they begin to investigate cases together. Canonical characters, such as Moriarty and Irene Adler (who becomes Holmes’s lover), are gradually added to the mix and given unexpected twists.

Meanwhile, in the UK, a pair of self-confessed Sherlock Holmes fans, writers Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss, conceived the notion of bringing Conan Doyle’s protagonists into a contemporary, high-tech London. The first series of Sherlock aired on the BBC in 2010, and its daring concept allowed the detective to manipulate modern technology in authentic Holmesian fashion to aid his investigations. He even has a website called “The Science of Deduction.”

The show has been hugely successful all over the world, especially with a younger audience. Its fast-paced, humorous, and intriguing plots are packed with references to the original stories, and its lead actors are also of similar ages to the literary Holmes and Watson when they first met. Benedict Cumberbatch’s Holmes is a geek, but despite his arrogance and, at times, lack of social skills, he is a fascinating individual. Martin Freeman’s Watson is a fragile mixture of independence of thought and unabashed loyalty to his friend. Indeed, his violent reaction to Holmes’s return after his “death” is more realistic than the rather tepid response of his literary counterpart. Andrew Scott’s Moriarty is perhaps the most chilling portrayal of the villain and a wonderful foil to Holmes.

Since he first appeared in print more than 125 years ago, Sherlock Holmes has been an almost constant presence in the media. Conan Doyle’s unstoppable creation has transcended literature to become a global phenomenon, continuing to fascinate and entertain fresh audiences.

Guy Ritchie’s Sherlock Holmes (2009) is set in 1890s London. Robert Downey Jr. is a bohemian Holmes, while Jude Law is a tolerant, if often exasperated, Watson. A sequel was released in 2011.

The BBC television series Sherlock brings Holmes and company firmly into the present day. Benedict Cumberbatch plays Holmes, while Martin Freeman’s Watson records their exploits in a blog.

MRS. HUDSON

Although she has no dialogue in the stories, landlady Mrs Martha Hudson is portrayed in numerous film and television adaptations, where she is used to show the human, sometimes humorous side of Holmes. She first made her mark in the Arthur Wontner movies as a cheeky Cockney (played by Minnie Rayner) who indulged in light-hearted banter with her lodger; in the Rathbone series she (Mary Gordon) was a motherly Scotswoman; and in The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, she (Irene Handl) was an East Londoner again, this time comically crotchety.

In the Jeremy Brett TV series, the character, played by Rosalie Williams, became more prominent. Mrs H’s affection for her lodger was obvious, but she grew irritated with his ways as the series wore on. In Guy Ritchie’s films, the landlady (Geraldine James) is stoical and rather stately, while in the BBC’s Sherlock, she (Una Stubbs) is fond but despairing of Holmes, declaring “I’m your landlady, not your housekeeper!”