7

Corporate Advantage

Large firm diversification activity has frequently been followed by a process of ignominious sell-offs and retrenchment.

Michael E. Porter, Harvard Business Review

In February 2017, Kraft Heinz made a £112bn ($143bn) hostile bid for Anglo-Dutch Unilever to create the world’s second-largest consumer goods company by revenue. Kraft Heinz was formed in 2015 through the merger of Kraft Food Group and Heinz and focuses upon food and drinks products. Unilever has major foods and refreshments divisions as well as home care and personal care divisions. Since 2015, Unilever has been shifting its focus away from slow growing food brands towards health and beauty products. The unwanted bid raised questions of the Unilever management team, and their shareholders, about whether they are managing the organisation effectively and whether other managers might do a better job. Implicitly it questioned whether Unilever’s businesses add benefit to each other or whether they are just a collection of separate activities. Should any of them be sold off? Not surprisingly, the bid got a sharp reaction from Unilever which said it had “no merit, financial or strategic, for Unilever shareholders. There is no basis for any further discussions.” Two days later Kraft Heinz withdrew its bid. However, some months afterwards Unilever has announced that it has turned its spreads business including Flora, Stork, County Cork and other low-growth brands into a separate business unit, perhaps as a prelude to a sale?1

Takeover bids for multi-business organisations, by acquirers that believe they can sell off some of the target business units and achieve a total value greater than they had paid for the whole acquisition, raise fundamental questions about the strategy of large multi-business firms:

- Why do multi-business firms exist?

- What businesses should they be in?

- How can the corporate centre add value?

These questions are the core concerns of the role of the corporate centre and corporate strategy.

Why Does the Multi-Business (M-form) Exist?

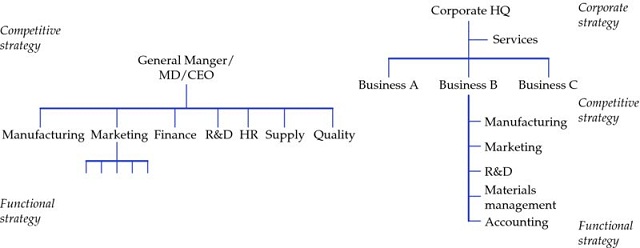

Historically, companies in the US were configured as a “unitary” whole, divided into functional responsibilities. The CEO’s major strategic role in managing this U-form was to coordinate the efforts of the various functions of the business (see Figure 7.1). However, the weakness of the U-form became apparent as firms grew in size and complexity and attempted to adjust to environmental changes. CEOs became overly involved in routine matters and neglected their longer-term strategic role. Functional managers saw their role as an end in itself. Coordination between increasingly stand-alone “functional silos” became more demanding and less fruitful.

Figure 7.1 The U-form (left) and the M-form (right)

Facing such problems, the large US companies Sears Roebuck, DuPont, General Motors and Jersey Standard moved to the “Multi-divisional” (M-form2) structure in the early 1920s. They were divided into semi-autonomous profit centres, later known as “strategic business units” (SBUs), responsible for a stand-alone segment of the organisation’s operations, such as a particular product, brand or national/regional market. In this structure (see Figure 7.1) the new business managers were able to specialise in the operations of their particular competitive arena and engage in “competitive” strategy – managing the customer/competitor dynamic as the ultimate source of profit. This freed corporate managers at the centre of the firm to focus on the overall strategic direction of the company, or “corporate” strategy. Here the concerns are the scope of the product markets, industries and geographies addressed by the organisation and how value may be added above the sum of the component parts.

By the late 1960s, over 80% of the Fortune 500 companies were structured in this way with similar trends in other industrialised countries. Now the M-form of organisation is the most prevalent structure among large businesses. It has established a new layer of management, the corporate office, and with it, corporate strategy.

What Businesses Should They Be In?

The original M-form adopters had a relatively narrow product-market focus. Their component businesses had similarities in terms of products, processes, markets, underlying capabilities or some other important attribute. These businesses can be described as related. However, companies faced limits to growth in their original product markets and, over the past 80 years, other factors encouraged further increases in product market diversity:

- Many companies had significant levels of free cash and managers tend to reinvest rather than return money to shareholders – this is linked to the fact that managerial salary and perks are often positively related to the size of their business empire.3

- The concept of the company as a portfolio of risky assets became popular in the 1970s and the risk of the bundle could be reduced by diversifying into different assets.

- The M-structure made the acquisition and divestment of business units easier than before as the messy tie-ups with other products/regions had been cut.

These factors encouraged expansion through related diversification, which is typically manifested as vertical and/or horizontal integration beyond the original narrow product-market focus.

Firms vertically integrate by buying other businesses upstream in their value chain (i.e. they buy into their supplier base) or downstream (i.e. they buy into the customer end) (see discussion about the value chain in Chapter 4). The original Ford Motor Company was integrated from the forests supplying the wood for the dashboard facia to the dealers selling the final, black product. Essentially vertical integration can be characterised as the “make” side of the “make or buy” decision. The benefits of vertical integration lie in the reduction of transaction costs. In particular, where businesses are dependent on one supplier or customer, then they are vulnerable to being held to ransom and hence might be better off buying that supplier or customer.4

Horizontal integration means buying businesses with products, processes or services that are complementary to those of other businesses in the portfolio. Typical manifestations are when firms buy other businesses selling the “same” products in the same industry (e.g. Morrison buying Sainsbury in the UK supermarket industry; Daimler buying Chrysler in the automobile industry) or buy other businesses with complementary skills (e.g. Procter & Gamble buying Gillette on the basis of complementary consumer branding capabilities). The value from horizontal integration lies in optimising economies of scale and scope. These kinds of gains are what managers often mean when they justify an acquisition on the grounds of “synergy” (more on synergy later). A firm might also gain through an increase in market power through being able to exert increased pressure on suppliers or customers, by reducing their choice, or by simply reducing competitive rivalry by acquiring rivals or complementary firms.

Where businesses are brought into the corporate portfolio and have no common characteristic, they can be described as unrelated diversifications. In extremis these are conglomerate companies of which Berkshire Hathaway (of Warren Buffett fame) is a classic example. Unrelated diversification initially emerged as a means for corporate growth when anti-monopoly legislation prevented related diversification. It was also encouraged by developments in the practices and theory of corporate strategy, particularly those emphasising the value of general management and the risk reduction of diversified portfolios. The value logic of unrelated diversification relies on the corporate centre acting as a better-informed and powerful “shareholder”. In stand-alone businesses, managers can maximise their “on-the-job consumption” by, for example, taking “business trips” to exotic locations with their wives. They can also disguise or hide poor performance. As part of a corporation the business is subject to the frequent reporting and the use of auditing functions to maintain the integrity of information. Managers are paid at market rates but are compelled to perform to high standards to maintain their position and the corporate level can intervene at an early stage to correct poor performance.

As the number of multi-divisional firms grew, so too did the interest in their financial performance, with the debate generally centring on the differences between related and unrelated diversifiers. In an early study, Richard Rumelt5 came up with the intuitively appealing conclusion that, in terms of value creation, related diversifiers outperformed unrelated diversifiers – “intuitively appealing” because “synergy” seems more logical among related businesses. Subsequent research has not unanimously supported this finding, and it seems that the characteristics of the business, its industry, regional and national context, the skills and imagination of management and the corporate strategy being implemented all have impacts on performance.

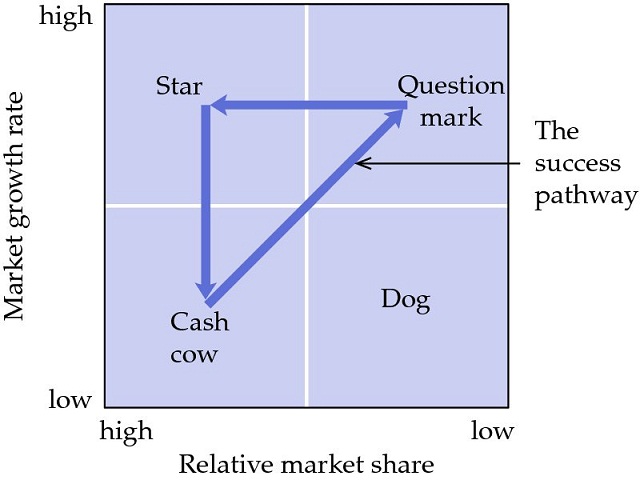

With these strategic options available to corporate centres, there was a need to make decisions about which direction of development was most desirable. This corporate strategy question of “where should we expand/invest?” gave rise to portfolio management tools, the most famous of which was the growth-share matrix or, more colloquially, the “Boston Box” (from its origins with the Boston Consulting Group). Beginning life in the early 1970s, as a doodled framework for the Mead Paper Corporation, the Boston Box evolved into the now-famous cash cows, dogs (initially “pets”), question marks and stars (Figure 7.2). It combined insights about the cost-reducing effects of the experience curve (and hence the importance of relative market share) with the notion of sustainable growth and fostered the orientation that cash-generating cows provided funds for cash-needy question marks so that they might become cash rich and growing stars. This virtuous cycle is illustrated in the figure. Dogs were either run down for cash or sold off.6

Figure 7.2 The growth-share matrix

Other more complex matrices followed.7 McKinsey, through its association with GE, developed the GE/McKinsey business screen – a well-known, nine-cell portfolio planning matrix with an “industry attractiveness” axis in place of the “market growth rate” and the business unit’s “competitive strength” instead of “relative market share” (Figure 7.3). The industry attractiveness axis combines an aggregate weighting8 of factors deemed important in the organisation’s industry (e.g. market size, projected growth, structure, profitability) while the competitive strength axis aggregates such factors as market share, advertising effectiveness, experience curve effects and others deemed relevant.

Figure 7.3 The GE/McKinsey business screen

Both matrices generated strategic imperatives (such as “invest”, “divest”, “harvest” and “manage for cash”) that depended on a business unit’s position in the matrix. Through these matrices the corporate direction of the firm could be established. For instance, if a business unit has a strong competitive position in an industry of medium attractiveness, then the GE/McKinsey matrix suggests that the parent should invest further, perhaps by making a horizontal acquisition. If a business unit has a dominant position in a very attractive industry, although it may wish to continue to increase its dominance, it is likely that regulators will prevent any acquisitions in the same industry. The business unit may then decide to make an acquisition in a related industry, such as buying a supplier. This is what Tesco PLC, the UK supermarket, is trying to do in 2017 with its £3.7bn bid for wholesale food supplier, Booker Plc.

By the end of the 1970s, nearly half of the Fortune 500 companies were using portfolio planning as a driver of their corporate strategy. What had begun as an analytic aid to one corporation had become a strategic model for all multi-business companies. Corporate strategists believed in the need for “balance” in their portfolio of companies, where balance extended to risk,9 cash generation, geographical spread etc. This logic legitimated the acquisition of businesses outside of the parent’s core activity and gave rise to a huge wave of diversifying mergers and acquisitions during the 1970s and 1980s. Share markets responded positively and “rewarded” diversification moves through increased stock prices. Businesses were treated as financial instruments to be bought and sold in the context of an existing portfolio of assets rather than to be managed. The stand-alone dynamics of the M-form structure facilitated this orientation, as did the movement towards controlling business units through financial outputs rather than managing them through behavioural inputs.

Unfortunately, the search for cash and risk balance brought more and more unconnected businesses together under one corporate umbrella, and the complexity of managing these different organisations became too much for even the most capable corporate office. As a result, the stock market began to devalue conglomerates and the stock value of the firm became lower than the sum of the market capitalisation of the separate businesses – the so-called conglomerate discount. The corporate raiders of the 1980s benefited from this by recognising that the sum of the parts of these conglomerates greatly exceeded the value of the whole. They borrowed huge amounts to buy these conglomerates and then “un-bundled” the component businesses, paid back their borrowings and became even richer on the proceeds. At the time of writing, though, commentators are beginning to take a more nuanced view of conglomerates and the value of diversification strategies. Although in sophisticated stock markets there is still suspicion about conglomerates, despite the success of several famous companies such as Berkshire Hathaway under Warren Buffett, there may be some evidence that wider diversification is beneficial in economic downturns and, in other geographic contexts where institutional structures are not well developed, conglomerates make a good deal of sense (see Chapter 9 on Crossing Borders).

By the end of the 1980s, the academic, business and investment worlds had largely turned away from portfolio management as a viable corporate strategy, despite the odd exception like GE. Even here it is worth noting that Jack Welch vigorously attacked anyone who described GE as a conglomerate, and, in the UK, anyone using the “C” word in a takeover contest was reprimanded by the Monopolies and Mergers Commission because the term had a deleterious effect on share prices (cf. Granada plc’s hostile takeover of Trusthouse Forte plc).

Even though debate continues as to the relative merits of related versus unrelated acquisitions, the overall picture is that most corporate acquisitions destroy rather than create value (see Angwin (2000) for a review of performance). As Goold et al. (1994) point out, companies have to overcome the “beating the odds” paradox, in that the probability of value-adding success through acquisition is empirically low. Indeed, the Tesco/Booker bid mentioned earlier has attracted Schroders, Artisan Partners and Hermes investment managers’ criticism for offering too much money and deflecting management attention from more important matters, which they perceive as turning around Tesco’s core business. They also mention the low probability of acquisition success.

While the portfolio technique was a major approach to determine which businesses to own, it became clear that the corporate centre had to provide inputs to add value to these businesses. Without group-based value, shareholders should invest in the separate businesses themselves without the imposition of expensive corporate overhead. This raises the questions, then, of how to achieve synergistic value between the businesses in excess of their value as individual units and how the corporate centre can bring about such added value.

Corporate Strategy in Practice

The beginning of the chapter described the bid for Unilever that has clearly forced it to reconsider the scope of its portfolio of businesses. The question has to be asked: how can the firm justify not breaking itself up, and spinning off separate stand-alone businesses in which shareholders can invest as they see fit?

There are two important interrelated questions here for those managing a multi-business organisation (and for those planning to invest in multi-divisional firms):

- What is the added value created by having a set of businesses in one “organisation”? To make sense from an economics/financial perspective, any multi-divisional business must have a greater ongoing value (Vc) than the sum of its component, stand-alone businesses (As, Bs, etc.): i.e. Vc > As + Bs + Cs. This is the age-old corporate dynamic of synergy. In non-economic terms, the quest for synergy has been expressed in terms of a dominant logic10 (the concept that a unifying idea links disparate business units) and/or in shared core competencies11 (a unifying set of resources or capabilities that underpin the value-generating processes or product of all business units).

- How should this grouping be managed to develop and maintain this added value? The answers to this question lie in the organisational processes of corporate strategy, with a particular focus on the role and activities of the corporate centre.

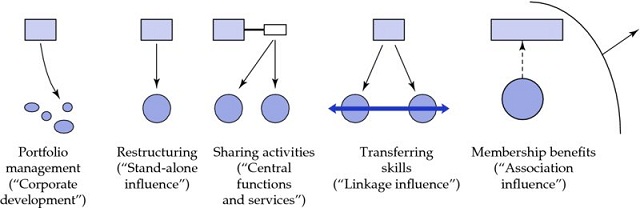

In addressing these questions, Michael Porter12 suggested four mechanisms of value creation. Michael Goold and his colleagues also identified four routes to parenting advantage,13 which, although named differently, are congruent with Porter’s classification. These mechanisms (Goold et al.’s version in brackets) are as follows:

- Portfolio management (“Corporate development”)

- Restructuring (“Stand-alone influence”)

- Sharing activities (“Central functions and services”)

- Transferring skills (“Linkage influence”).

These four styles can be represented diagrammatically as shown in Figure 7.4.

Figure 7.4 Value-adding approaches of the centre

Portfolio management (corporate development)

Despite the negative view of the portfolio-based conglomerate, this does not mean that it no longer exists as a business technique, nor that those that use it inevitably perform badly. GE, even post Jack Welch, remains a formidable corporation that provided 30.9% returns to shareholders in its 2003 financial year and has averaged a 15.8% annual return from 1993–2003. These impressive returns are despite the fact that the company was a classic conglomerate, with a portfolio of four slow-growth “cash generators” in insurance, consumer and industrial products, advanced materials and equipment services supporting seven “growth businesses” in commercial finance, consumer finance, energy, transportation, healthcare, media and infrastructure. The smallest of these 11 businesses (infrastructure), with a 2003 turnover of US$3.5bn, would be comfortably placed in the Fortune 500 in its own right were it not in the GE stable. GE divests poorly performing businesses and acquires others that have more potential for value generation – a classic portfolio orientation but one that seems to work well for this company.

Restructuring (stand-alone influence)

In its purest sense, “restructuring” relies for its value-adding potential on (1) the insight of the corporate office in spotting and buying an underperforming business at a low price and (2) its capability to then address the weaknesses of the business and bring it to its full potential (and then re-sell it at a higher price commensurate with its new value). The sale rarely happens in practice and this form of corporate strategy more generally entails the corporate layer (including the CEO) exerting ongoing and direct stand-alone influence on the actions and decisions of otherwise autonomous business units.

Business units may still be fully autonomous with respect to other business units but they are subject to strategic and operational direction and control from above. Influence occurs through a variety of mechanisms, ranging from direct commands (“do this!”) to indirect control through policy manuals, pronouncements or a set of prescribed targets (“achieve this!”). The frequency, intensity and focus of interaction depends on the culture of the corporation and the personality of the CEO, and varies from the “light touch” of strategic reviews to the “blowtorch” inquisition of every negative variance.

Classic restructurers make a practice of acquiring companies in mature, asset-based industries providing essential goods and services. Their criteria for purchase often include the business needing to have a leading position (and, hence, a good cash flow) and a well-known name in its market and, most importantly, be performing at a level below its capability. Having acquired the business, the restructurer will send in a team to lift operating efficiency, reduce waste and excess overhead, cull non-profitable products and customers, divest non-core assets and identify strategic focus and new management. The local management then can run the business in a completely decentralised way, although heavily incentivised through substantial bonus payments or the threat of dismissal, to meet fiercely demanding operating and growth targets “agreed” with the parent body.

For this type of corporate strategy, the centre is an active manager of its businesses rather than the passive investor of the portfolio management approach. However, it is still difficult for the centre, having completed any restructuring, to add value on an ongoing basis over that of a motivated, informed set of business managers. Goold et al. refer to the “10 percent versus 100 percent” paradox, wherein it defies logic that “part-time” corporate managers can, by spending only 10% of their time in the business, do better in terms of business performance than the dedicated business managers spending 100% of their time on the same issues. If this were to be the case it would suggest a chronic incapability in the business managers, and the solution to that problem is obvious.

Sharing activities (central functions and services)

Parenting advantage, or core competence, from this category of corporate strategy, where central functions and services are shared, arises from functional or process experts at the corporate level. These individual or departmental experts either augment the existing expertise in the business or substitute for it.

In an augmenting structure, the central resources have the time and resources to develop world-class capability in their functional expertise whereas the business function, through time and resource restriction, must focus on the day-to-day operations. One corporation in the automotive components industry in the UK has a “kaizen” (continuous improvement) team in each of its businesses but also has a corporate team that brings best practice kaizen processes to the businesses. In a corporation with an augmenting orientation, the business units may still have autonomous capability but be subject to compulsory oversight by the corporate function (an influencing relationship) or may have a voluntary consultancy or customer–supplier relationship. A classic example of a mix of compulsory/voluntary inputs is the corporate manufacturing services function of the American company Cooper Industries. New businesses acquired by Cooper underwent a compulsory process of “Cooperisation” by the Manufacturing Services group, who worked with the operations staff of the acquired business to transfer Cooper’s processes and know-how. Once businesses had become fully fledged members, however, the Manufacturing Services group intervened only on invitation from the Division Manager.14

Substitution means that particular functions or facilities are taken out of the businesses and centralised at corporate level. As well as the standard “service” functions, such as taxation and legal offices, more strategic functions, including distribution, branding, quality, R&D, finance, manufacturing and others have been centralised by various M-form companies around the world. Synergistic value is added through economies of scale, benefits of functional specialisation, and increased focus on a smaller number of key processes at operational level. Businesses are no longer completely autonomous in their overall day-to-day functioning, but rely on “sharing activities” with the corporate function to work as a business. A typical example of substitution took place at a UK based multi-business automotive company that centralised the purchasing of steel. The corporate centre realised that autonomous purchasing by the businesses was not exploiting the potential supplier power that concentrating the buying might bring. Annual savings of over £3m were achieved by this consolidation.

To truly add value at the level of sharing activities, Goold and his colleagues emphasise that the corporate centre has to overcome the “beating the specialists” paradox. Stand-alone businesses are free to outsource any function or process to outside specialists who have greater capability and/or higher efficiency in that arena. This is happening on a worldwide scale, as companies outsource call centres, software writing, manufacturing and other functions to North Africa, Mexico, India, China or any other country with comparative advantage. To justify its place as the “external” provider of a business function/process, the corporate centre needs to show that it has a sustainable competitive advantage over other external providers. The fact that the corporate centre can provide a central service better than the businesses can do separately is only one part of the corporate strategy question. An increasingly important second part is: can the corporate centre provide that service better than a world-class specialist?

Transferring skills (linkage influence)

Corporate strategy in this category of transferring skills is based on interactions between the businesses. The primary source of parenting advantage lies in the transfer of knowledge-based best practice and competitive capabilities and occurs in practice through such mechanisms as staff transfer, cross-business work teams and shared objectives. Economists describe this as facilitating economies of scope wherein related business units share specialised physical capital, learning and knowledge, management expertise and so on. Of all of the categories of corporate strategy, this is the level that seems to have most theoretical support as having the potential for adding value beyond the individual businesses through the development of core competencies that transcend business boundaries.

Canon’s capabilities in optics, mechanics, and electronics transcend its product–business boundaries in printers, cameras, copiers, faxes, etc., as do Sony’s focus on miniaturisation and Walmart’s complex capability in logistics. Honda’s complex matrix structure in Europe aims to exploit a core competence in engine design as well as economies of scale across all its country-based businesses and its product groupings of motorcycles, lawn mowers and cars. Similarly, 3M’s obsession with innovation is primary whereas the product groups resulting from this obsession are the secondary consequence of this competence. Large corporate staffs often manage these pan-corporate competencies; they require ongoing effort, commitment and expense. Another requirement is to do battle with business/country/product managers, who rarely relinquish their autonomy without a fight – a fight they continue to engage in even when the benefits of sharing seem well established.15

Goold et al. (1994) suggest that the paradox to overcome here is one of “enlightened self-interest”, wherein the managers of stand-alone businesses could link with other businesses equally well outside of a corporate framework. While such sharing is theoretically possible for stand-alone businesses, it is unlikely because these (related) businesses would normally be competitors and the risk of opportunistic exploitation is difficult to eliminate. The risks are particularly acute where the sharing involves knowledge-based competencies. Once the knowledge is transferred from one party there is little incentive for the other party to reciprocate or to maintain the relationship unless there are significant ongoing and/or future gains that are contingent on continuous dealing. Many well-intentioned alliances flounder when one party or other begins to feel that their outcomes from the engagement are minor compared with those of their partner. Once businesses are part of the same corporation, however, these issues of exploitation theoretically disappear because all parties are on the same team and therefore have a mutual interest in the overall value of the interactions.

Hence, corporate strategy of this type offers the potential for substantial value creation, but the force of a corporate hierarchy is generally needed to ensure the development and maintenance of pan-business capabilities, as business units cease to be autonomous in the conventional sense of stand-alone operation. While not necessarily dependent on other units or functions for day-to-day operating, they become strategically interdependent on one another or on a corporate function or activity they all share. The businesses are participants in or users of important strategic resources that they cannot unilaterally direct or control. Their delegated, stand-alone activities are fewer and narrower and performance measurement is more ambiguous. Rarely do the managers in the businesses become completely comfortable with these constraints and rarely do they totally cease struggling against them.

Corporate Advantage and the Role of the Centre

The unwelcome bid by Kraft Heinz for Unilever, which opened the chapter, asked a pertinent question of a multi-business firm: is the value of the whole greater than the sum of the parts? This questions directly whether the corporate centre is adding value beyond the intrinsic components of the firm.

If we viewed Unilever as an unrelated group of businesses, then corporate managers should be better-informed shareholders who have access to their businesses in a way that outside shareholders do not and they can intervene earlier if there are signs of underperformance. Being closer to the businesses, they can ask more relevant questions of local managers and replace those who are unable to achieve. The corporate centre is also able to allocate resources and capital more efficiently than external markets. Clearly Kraft Heinz did not perceive Unilever’s corporate centre to be adding sufficient value to all parts of the business and felt they would be able to reduce costs, something they have a great deal of experience at doing, dispose of “non-core” assets, and make better use of brands within their own group.

If we viewed Unilever as a set of related businesses, then we would expect to find value added from the sharing of activities and linkages between the businesses. The corporate centre would provide centralised facilities – coaching at both general and functional management level and coordinating and driving the inter-business relationships. It may be that Kraft Heinz believed that this was not achieved to the extent that it could be, or that some of the business units might be better off somewhere else.

Kraft Heinz’s hostile bid poses a generic question for all multi-businesses: why should their portfolios not be floated and become truly autonomous without the encumbrance of an additional layer of expensive management? Although ultimately unsuccessful in its bid, the fact that Unilever has moved quickly to repackage its spreads businesses into a unit, and earmark for disposal, suggests that Kraft Heinz may have had a point. Also, perhaps, with such a disposal, Unilever is removing a reason for Kraft Heinz to rebid. Kraft Heinz’s question was a good one.

Corporate Advantage Key Learnings Mind-Map

Having read and reviewed this chapter, outline what you believe to be the key learnings from the chapter and the relationships between these on the note pages below.

7-1 Z Enterprises: Parenting Problems

Chen Song, the CEO of Z Enterprises,16 had a dilemma. Although Z was profitable and growing, it had failed to achieve a number of operating targets for the most recent financial year. The key among these were Quality, Inventory control and product Cost reduction (Table 7.1). The US-based board, on which Chen Song sat, had expressed their disappointment with these shortfalls and had asked him to prepare a report detailing how he planned to get these measures back on track for the following year.

Table 7.1 Selected operational outcomes (targets) for latest financial year (best in bold)

| A | B | C | Z | |

| Quality* (%) | 6.12 (4.5) | 4.54 (4.0) | 3.03 (3.5) | 4.51 (4.0) |

| Inventory (turns) | 16.34 (20.0) | 22.18 (20.0) | 15.17 (24.0) | 18.23 (22.0) |

| Cost (%) | 27.24 (25.0) | −2.1 (−4.0) | 0 (−6.0) | −3.5 (−5.0) |

*These measures are aggregates: i.e. quality, expressed as a percentage of output that is faulty, combines production and customer reject figures; inventory measures all stock (i.e. raw material, components, work in progress (WIP), and finished goods (FG)) and is expressed as stock turns; and cost is the real (i.e. inflation adjusted) decrease in overall direct product costs for the year. |

||||

Z is a corporation made of three businesses which design and manufacture parts for the domestic and export automotive industry. They all use capital-intensive processes in value-added manufacture and have to meet the same quality, cost and delivery standards; 70% of the Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) customer base is common to all three with over 90% being common to at least two. The managers and technical staff and many of the senior shopfloor personnel have expertise in a variety of the processes that contribute to increasing productivity and quality such as total quality management (TQM), business process reengineering (BPR) and just-in-time (JIT) inventory control. The Managing Directors (MDs), along with the Corporate Finance Office and a small Human Resources department, report to Chen Song as part of the Corporate Management Board (CMB) which meets monthly, hosted by each business in turn (Figure 7.5).

Figure 7.5 Organisational structure of Z’s Corporate Management Board

A in Table 7.1 was the original business of Z enterprises. It had originally been a state-owned enterprise (SOE) making parts for agricultural machinery but had been bought by an overseas group and switched to manufacturing exhaust systems for automobiles after China’s acceptance into the WTO. Chen Song had been the Managing Director of A when it was acquired. He had impressed the new owners with his energy and dedication and the way in which he had transformed the culture and operations of A from an inefficient, bloated, rundown SOE to a productive, lean, state-of-the-art company.

A, a Shanghai-based operation, now employs 530 people (down from over 2,000). The MD, Wu Min, who had risen through the engineering function to become Chen Song’s understudy, is regarded as a tough but fair manager who engenders a shared passion (and expertise) for cost reduction in all employees. B and C were acquired in the past three years. They had both been start-up companies aimed at cashing in on the growing automotive industry. B, located near Guangzhou, has 370 employees engaged in the manufacture of various pressed metal components. MD Yu XiuBao, part of the original start-up syndicate, is an aggressive, entrepreneurial woman who believes that inventory is the basis of all (manufacturing) evil. C, close to Beijing, employs 250 people in generating the highest margins in the corporation from its high-technology components for sophisticated “vision systems” (“mirrors”). MD Song Xiaodi is well-liked but has a reputation for sometimes favouring analysis over action, except when it comes to his obsession with quality. The managers of C feel superior to their counterparts in A and B. This sense of superiority is well known by the others and is strongly resented.

In addition to a salary, each MD earns a significant bonus based on a percentage of his/her business’s profit. Business (and hence corporate) profits had initially grown rapidly but the industry was maturing, sales growth had plateaued and there was increasing pressure on price. Hence it was clear to Chen Song that more returns needed to be squeezed from internal processes. The businesses currently operate as stand-alone, autonomous units with the only structured contact being between the MDs at the monthly CMB meeting. As well as direct instruction to the MDs at these meetings (and individually), Chen Song had often pointed out to the group that each of the businesses was excellent at some things but poor at others (Table 7.1) and that it would benefit everyone if this “best practice” was shared. “We have islands of excellence – we need bridges!” he exhorted. The MDs insisted that they did share knowledge but, in reality, inter-business relationships were highly competitive; there had been too many examples where managers had “forgotten” to pass on necessary knowledge to their counterparts outside of their own business. Even Chen Song’s practice of rotating the CMB meetings between businesses was to avoid charges of a “Shanghai” bias that would arise from meeting in his office in Pudong (Shanghai).

Chen Song pondered his dilemma. When he was a business MD he had vehemently defended business autonomy and the right to manage “his” business without corporate interference. “Let me run it and if you’re not happy – sack me” was one of his typical responses. He knew that his own MDs would be just as aggressive. Despite this, he could see clearly that without some corporate intervention the business improvement in their areas of weakness would take far too long. Having thought about it for some time he could see a variety of options, each with its own benefits and challenges.

What are the options, their strengths and weaknesses, and what would you recommend?

Some suggestions

Some suggestions

Chen Song faces a dilemma that confronts many who are in charge of multi-divisional companies. The businesses and their MDs are fiercely autonomous and want to stay that way, but this desire for separateness, what Prahalad and Hamel (1990) refer to as the “tyranny of the SBU” (Strategic Business Unit), prevents the development of pan-corporate competencies and/or the sharing of best practice. From Table 7.1 in this case we can see, for example, that business A is the best at cost reduction. Hence the corporation can benefit from A sharing its expertise with B and C while at the same time benefiting from their knowledge of inventory control techniques and quality management, respectively. Similarly, B and C will improve by sharing with each other and A. Note that although each business is meeting its target on one of the measures, the corporation as a whole is not meeting its targets on any measure. Chen Song has three major options (and, of course, any mixture of the three) each of which has advantages and disadvantages:

-

Use direct influence on stand-alone units

In this corporate style, Chen Song would be a “guru”. He would work directly with each MD to improve the areas of shortfall. So, for example, he would work with Wu Min to improve A’s quality and inventory management. This might involve such things as changing the bonus structure to incorporate more measures than just profit (i.e. an internal “balanced scorecard”), insisting that A hired more experts or used outside consultants to focus on those areas, or merely threatening to replace Wu Min if improvements are not forthcoming.

The advantages of this approach are that it maintains the focus of the businesses on their particular product/market/customers and their particular problems (what the economists would call “optimising economies of specialisation”). Also, it does not add to corporate overheads and keeps the MDs happy in that they are running autonomous businesses. The disadvantages are that it does not promote any pan-corporate competencies but maintains the “islands of (different) excellence”. It also puts Chen Song in a “supervisory” role and will take up all his time. It is unlikely that he is an expert in all three processes, therefore the potential for conflict between him and his subordinates is high, particularly if business priorities change and he is forced to change focus.

-

Develop corporate centres of excellence

In this option the corporate centre develops competence in a process or function. For example, Chen Song could hire a Corporate Quality Manager who would put together a team of experts to form the Corporate Quality Department. There are three general mechanisms by which such corporate services operate:

- As advisory experts to the business function to be called on when needed by the business or to be imposed if targets are not met.

- As a centralised function wherein the responsibility is at corporate level, not at business level. Functional employees, although perhaps located in the business, are controlled and administered from the corporate level.

- As a matrix-like amalgam of (a) and (b), whereby the business function reports to both the MD of the business and the corporate department. This is a very common structure for the finance function, for example, which often reports to both the local business manager and the corporate finance function.

With arrangements of this sort, the corporate centre becomes a facilities manager. The advantages are such that Chen Song can be more confident that business functions will be directly focused on corporate level targets without him having to try to influence this through the MDs and spending a lot of time on it. The corporate-level functions, free from the grind of day-to-day operations, can maintain a world-class capability by visiting and benchmarking world leaders and attending training events. They can then pass this expertise on to the business level through normal interactions (tacit knowledge is shared by interaction). The disadvantages lie in the added costs at corporate level (and the MDs are always very sensitive to allocated overhead costs) and the fact that it may engender an “us (business) versus them (corporate)” dynamic. Mr Chen would need to be sure that the benefits would outweigh the added cost (including the costs of the turmoil of “start-up”) because he can be sure that the MDs and his corporate bosses will notice if they don’t.

-

Broaden the responsibility of the businesses

With this approach, Chen Song changes the roles of the MDs. Currently they “own” their business and are rewarded in both monetary and psychological terms for championing their own causes. It is the sense of what they “own” that needs to change under this approach. The MDs need to see themselves as “stewards” of the businesses and (part) “owners” of the corporation. Some mechanisms for moving to this approach include:

- Changing the bonuses of the MDs from being based on business results to being based on corporate results, or a combination of both (e.g. the bonus is based on business results but is only triggered if the corporation achieves its targets).

- Making the MDs accountable for overall operating processes (i.e. corporate level) rather than just the business processes. So Song Xiaodi might become the corporate quality manager, for example, as well as the MD of C. In this way, he has a vested interest in sharing his expertise around the other businesses because his quality responsibilities have been broadened. In a similar way, the MDs of the other businesses can be given corporate responsibilities.

- Ensuring that robust inter-business processes, such as regular meetings, exchange of employees, co-located functions (i.e. multi-site), shared databases, joint presentation to customers etc. are established and maintained.

In this approach, the corporate centre (Chen Song) acts as a “boundary rider” ensuring that fences are being knocked down and not rebuilt. It has the advantages of developing truly pan-corporate best practice across a number of dimensions and getting the MDs (and eventually all employees) to have a broader perspective. Its disadvantages lie in the additional costs, including those of complexity and hassle and the strong possibility that by getting managers to focus on both the business and the corporation they will not focus sufficiently on either. As somebody once said, “more than one objective is no objective”.

So now what would you do?

![]()

7-2 GE: A Conglomerate By Any Other Name?

In 1879, Thomas Edison invented the electric light bulb and by 1890 had organised his various businesses into the Edison General Electric Company – now the General Electric Company (GE). GE is the sole survivor of the Dow Jones index of 1896 and was number 4 by revenues in the 2009 Fortune 500. While in the top ranks by revenue, the company has failed to translate its revenues into returns to shareholders. For the 2009 financial year, its total return to shareholders was a loss of 0.4% (ranking the company 404th in the top 500). Over the 10-year period up to 2009, GE had lost an average of 8.9% per year for its shareholders, which ranked it in 351st position. A lot of this underperformance is attributable to the company’s high exposure to financial markets during the Global Financial Crisis. Nevertheless, such performance levels do not look good for Jeff Immelt who, in 2001, was appointed GE’s 9th CEO as successor to the legendary Jack Welch who, in his 20-year reign as CEO, had overseen the growth of the company from $13bn to several hundred billion and was famous (notorious?) for managing steady income growth.

GE comprises five segment divisions made up of various businesses (Table 7.2). On the basis of 2009 sales revenue, the smallest of these divisions (Consumer and Industrial) ranks at 243 as a stand-alone company in the Fortune 500, above such firms as Eastman Kodak and Yahoo. The largest (Capital Finance) is at number 40 in line with such well-known companies as Dell, Goldman Sachs and Pfizer. Jeff Immelt, however, like his predecessor, has always denied that GE is a conglomerate: “a conglomerate generates returns by trading in and out of businesses; it’s basically a gigantic mutual fund. By contrast, GE generates returns by undertaking projects that only it has the wherewithal to undertake: the biggest, the most difficult, the longest term. Scale is one of GE’s traditional strengths” (Fortune, 4 May 2004).

In its report on its 2009 performance, GE does refer to its “portfolio” and shows how the composition of that portfolio has changed from “early in the decade” to “now” then to the “future” as a consequence of an overarching corporate strategy (Table 7.2, Table 7.3, Table 7.4 and Table 7.5). The report also indicates how the majority of future profits are seen to come from “Infrastructure”, and while “ongoing NBC–Universal investment” is foreshadowed, this is in the context of operating via a subsidiary relationship rather than full operational ownership, as NBC was classified as “held for sale” at the end of December 2009.

Given the diversity and size of its past and ongoing operations, and its acquisition/divestment approach to managing its past, present and future strategy, it is difficult to see how GE is not a conglomerate even in the terms of its current CEO (see Jeff Immelt’s quote above).

Table 7.2 GE’s 2009 segments (GE Annual Report)

| Division | Products/businesses | |

| Capital Finance | CLL, Consumer, Real Estate, Energy Financial Services, GEGAS | |

| Revenues: $50,622m | Profits: $2,344m | |

| Consumer and Industrial | Appliances and Lighting, Intelligent Platforms | |

| Revenues: $9,703m | Profits: $400m | |

| Energy Infrastructure | Energy, Oil & Gas. | |

| Revenues: $37,134m | Profits: $6,842m | |

| Technology Infrastructure | Aviation, Healthcare, Enterprise Solutions, Transportation | |

| Revenues: $42,474m | Profits: $7,489m | |

| NBC-Universal | Revenues: $15,436m | Profits: $2,264m |

Table 7.3 GE portfolio and strategic orientation: “Decade ago”

| Segments: | Insurance |

| Capital Finance | |

| Infrastructure | |

| Plastics, Media and Consumer & Industrial | |

| Corporate Strategy: | Reduce Risk and Investment |

Table 7.4 GE portfolio and strategic orientation: “Today”

| Segments: | Capital Finance |

| Infrastructure | |

| Media and Consumer & Industrial | |

| Corporate Strategy: | Reposition, Simplify & Invest |

Table 7.5 GE portfolio and strategic orientation: “Future”

| Segments: | Capital Finance |

| Infrastructure | |

| Consumer | |

| Corporate Strategy: | Growth & Value Creation |

7-3 easyGroup: Easy Does It?

In 1995, Stelios Haji-Iannou, only 27 years old and with a loan from his family, launched easyJet. Starting with just six hired planes working one route, by 2016 it had 200 aircraft flying 820 routes to 30 countries and is the second-largest airline in Europe by numbers of passengers flown per year. easyJet has a dense point-to-point network, linking major airports with large catchments with very frequent flights. easyJet’s large fleet of over 200 aircraft are modern, and relatively environmentally friendly. The brand is very strong, with a high degree of consumer awareness of the company’s orange colour and logo.

easyJet aims to be the lowest fare on a route and a low-cost philosophy permeates the business. Tickets are not issued to passengers and around 90% are purchased online. Because 100% of sales are direct to consumers, easyJet does not pay intermediaries. The fare system is dynamic: “the earlier you book, the less you pay”. There are no free in-flight refreshments, although they can be purchased. Travellers are expected to clear up after themselves and this helps to reduce the amount of time aircraft need to remain on the ground. There is no distinction between economy or business class.

While easyJet went from strength to strength, Stelios started up other new ventures. This dynamic, serial entrepreneur, as he describes himself, is a highly energised presence, a terrific talker and full of ideas and reasons. His mission is to “paint the world orange”. easyCar resulted from his observation that the cost of renting cars from airports that easyJet served was a “rip-off”. With easyCar, a Mercedes A-class, in the trademark orange of the group, can be rented for a very competitive price. Other ventures include easyBus, easyCruise, easyHotel, easyInternet café, easyMobile, easyOffice, easy4Men and easyCinema.

easyCinema is a good example of the way in which Stelios identifies and establishes his business ventures. It followed the familiar Stelios mission of identifying industries where a new venture can compete on low cost, innovation and fun. In cinema, Stelios observed asset underutilisation – with only one in five seats on average being sold – inflated prices, which also did not reflect that films become less valuable over time, and overpriced popcorn and coke for sale. Stelios felt that an “easy” makeover was called for. He searched for a location to offer a cinema based on easyGroup values. Eventually, he found an ageing multiplex in Milton Keynes, a large conurbation some 40 miles north of London.

The interior of the once-lavish multiplex was ripped out and the whole complex painted a bright orange, much to the annoyance of passers-by. Gone were the popcorn, drink and ticketing facilities. In the words of his posters, “If you really want to eat popcorn, bring your own, but don’t make a mess!” Tickets are purchasable over the internet. Through payment by credit or debit card, the customer can print out a bar code for use at the entry scanners in the multiplex. Prices start at 20p per ticket, compared with around £4.60 per ticket at neighbouring cinemas.

With just two weeks to go before opening, Stelios did not have films to show at his new cinema. The only major blockbuster to open near this time was The Matrix Reloaded. However, none of the four major film distributors was interested in supplying Stelios with their films when they heard that he would be selling tickets for just 20p per person. He received many criticisms over the lack of staff at his facility, concerns over public order and health and safety, and whether piracy could be avoided. Stelios interpreted these as stalling tactics as the film distributors were not happy with his intention to charge low prices. To remove the potential loss distributors might incur through low box-office takings, Stelios decided to offer them a £2,000 cash lump sum for a week for a film three weeks post-opening, which he had calculated to be the entire box-office takings for such a film at this stage in the USA. He did not receive acceptance and so still had to find films for his cinema. Fortunately, he was able to procure films from a leading independent producer, Pathé. While Stelios was unsure that The Little Polar Bear would really provide competition for The Matrix Reloaded, which would be showing across the street at the same time, it was, at least, a new release.

With film distributors controlling 90% of the market, Stelios had to find a way to deal with these large players. For their part, they could not be seen to collude against him because that would be anti-competitive and illegal. However, Stelios’s lawyers suggested that their uniform action to date could be deemed to be evidence of tacit collusion. When this observation was sent to the distributors in a formal letter, the net result was that they then provided Stelios with some films. Although not the blockbusters he had hoped for, they were, nonetheless, new releases.

Just days before launching the new cinema, easyGroup and Stelios launched a public relations offensive, with widespread advertising on radio, internet and television, as well as the prominent display of provocative orange posters on buses, taxis and billboards. Stelios himself walked around Milton Keynes with a billboard proclaiming: “The end of rip-off cinema is nigh!” Followed by television cameras, he entered shopping malls and the foyers of competitor cinemas where he was forcibly ejected. There is little doubt that the people of Milton Keynes were aware of Stelios’s enterprise and many would have met him or at least heard of his evangelical tirade.

Despite a few technical difficulties on the opening night, customer volumes during the first week were good, despite only having a “little polar bear” rather than a “matrix”. Even when customers were in their seats, the Stelios offensive continued. Although they had entered for as little as 20p per ticket, Stelios explained that the film distributors were forcing him to pay £1.30 per person. Could they put a further contribution into the bucket he was passing around? The goodwill of the customers was evident as people did contribute. Stelios then announced that these funds would in fact be donated to a local hospice. The point, however, had been made: Stelios was trying to protect his customers by providing entertainment at a reasonable cost.

Despite a slackening in demand at easyCinema in the ensuing weeks, there is evidence of an underlying level of support. However, Stelios realises that for the project to really take off, he needs to be able to show the new blockbusters. To gain leverage over the distributors, Stelios has engaged US competition lawyers (if you lose litigation in the USA, you do not pay the other side’s costs). The lawyers have found a 1950s legal precedent in favour of a cinema exhibiter who faced producers ganging up against him. Stelios is now considering opening further cinemas in London to extend the concept.

Meanwhile in the group, easyJet was floated on the London Stock Exchange in 2000 – although with easyGroup remaining the largest shareholder and taking more of a back-seat role. Other ventures were not progressing quite so well. easyCinema was struggling to get the blockbuster films it needed, the internet cafés were losing £3m per month, easyCar business was losing money, easyInternet Café shut down in 2009 having made losses of £96m in five years and in the same year easyCruise was sold off to Hellenic Seaways for £9m. easy4Men is no longer in operation and easyMobile closed in 2006. And yet the group continues to engage in new ventures such as FastJet, easyPizza, easyProperty and easyFoodstore. In the meantime, Stelios is threatening to vote against the reappointment of the chairman of easyJet as he is fiercely opposed to the business’s plan to greatly expand the size of the fleet. Maybe everything is not so “easy” at easyGroup?

7-4 Tata: Staying Power

Hailed as triumphs today, Tata’s acquisitions of Tetley, Corus and Jaguar Land Rover (JLR) were perceived as extravagant at the time, saying more about Indian imperial ambitions than commercial logic. How was success achieved?

The largest privately owned Indian company, Tata Group, has interests in steel, hotels, telecommunications and consulting. Although the Tata Group has had an international outlook from the very start, by the late 1990s international sales only accounted for 12% group turnover. However, it subsequently pursued internationalisation with acquisitions including Tetley Tea in the UK in 2000, Corus, the Anglo-Dutch steel giant in 2007 and, in 2008, Jaguar Land Rover group (JLR). In 2000, Tetley Tea was the largest takeover of a foreign company by an Indian one in a US$432m leveraged buyout. Up until this date, Tata acquisitions had been small relative to the group. However, in 2004 Ratan Tata in an interview with Business Week (26 July 2004) stated the need “to internationalise in giant strides, not in token, incremental steps”. There followed much larger acquisitions with the purchase of Anglo-Dutch firm Corus by Tata Steel in 2007 for US$11bn – the largest deal out of India to date and the fourth largest ever in the steel industry. In 2008 Tata Motors purchased the Jaguar and Range Rover car brands for US$2.3bn. At €1.7bn (£1.4bn, $2.2bn) the acquisition of JLR from struggling Ford Motors gave Tata two well-known brands and enlarged its global footprint. But critics asked how a company known for commercial vehicles and cheap cars (the Nano) could do better than a gargantuan of the global auto world, which had pumped billions into the brands, when there were no obvious synergies.

Most of Tata’s companies are growing through acquisition. Tata Chemicals has become the world’s third-largest manufacturer of soda ash after acquiring three plants of Brunner Mond and complementing it through acquiring cheaper sources of natural soda ash from Magadi Kenya where the unique operation makes it one of the lowest cost producers in the world. Tata Power has purchased two major equity stakes in major Indonesian thermal coal producers. TCS acquired Swiss-based TKS-Teknosoft to possess marketing and distribution rights to the QUARTZ® platform for wholesale banks, to add new products in the private banking and wealth management space as well as its record of successful implementation of large complex technology financial projects. Tata Steel’s acquisition of Corus allows access to EU markets and high-quality steel products and the acquisition of Singapore’s NatSteel and Thailand’s Millennium Steel helped strengthen presence in higher-value finished products. This also helps avoid tariffs on imported finished steel products. Sometimes, the pressure for overseas acquisitions has come from within India. In 2007, VSNL’s monopoly on international long-distance voice in India, which accounted for nearly 90% revenue, came to an end. In response, the company entered new domestic businesses such as enterprise data and internet telephony as well as acquiring submarine cables under the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and more than 200 direct and bilateral agreements with leading voice carriers. Its software system which facilitates the location of roaming mobiles, is in use at 95% of telecom operators in the world and VSNL is now the third largest carrier of voice minutes in the world.

Tata companies have tried to develop an ability to understand the culture of the country where their acquisitions take place in order to be able to manage their acquisitions skilfully. Contrary to CORUS’s expectations, the post-acquisition period did not result in massive upheaval and change but a laissez-faire approach. A Strategic Integration Committee (SIC) chaired by Ratan Tata was formed to facilitate integration and create a virtual organisation across the combined business. The group focuses upon the sharing of best practices, manufacturing excellence, cross-fertilisation of R&D and the rationalisation of costs across businesses which are coordinated by a Program Office. Joint teams, formed from both organisations, work together to identify areas for change. This presents a paradox of how an emphasis on collaboration rather than control as an adaptive model allows the distinctiveness of the Tata Brand to persist.

With mergers and acquisitions being of increasing significance to the Tata Group, it is salutary to examine the integration of Corus. Ratan Tata, chairman of the Tata Group that owns Tata Steel, was keen on Corus because of its sophisticated steelmaking technologies, its broad customer base in Europe and its size – four times bigger than Tata Steel in terms of shipments. The deal made Tata Steel the world’s eighth-biggest steel producer. At the time of the transaction, Tata Steel was one of the world’s strongest steelmakers in terms of profit margins, while Corus’s profits record over the past decade had been decidedly patchy and indeed at one point the firm nearly collapsed.

Unfortunately, Corus became one of the biggest European casualties of the global recession starting in late 2008. Corus made EBITDA losses of more than $1bn in the first nine months of 2009 and more than 5,000 jobs were cut, mostly from UK plants. For the financial year 2009/10 Corus’s dire financial state has had a big impact on Tata Steel’s overall profits. Although the company’s India-based operations have been relatively unscathed by the recession, thanks to robust domestic growth allowing earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation of $1.3bn for the nine months, Corus provided a $643m loss. Nevertheless, in the final three months Corus recorded positive EBITDA of $142m causing some industry observers to say: “even though there are short-term problems, over a longer period the Corus deal will turn out to be a wise move for Tata”.

One London-based banker was less enthusiastic about the deal. He said: “Mr Tata badly wanted to do this acquisition but in my view he paid a very full price for Corus. It also diverted the company from other possible approaches [to building up its steel business], especially in Asia. I don’t see this as a positive move from either a financial or a strategic point of view.” There were also questions over whether Tata has been correct to run Corus essentially as a stand-alone operation, with its management left very much to Mr Adams. Also, confusingly for many outsiders, H. Nerurkar, who became Tata Steel Managing Director, did not have any responsibility for Corus but instead had power only to direct the company’s operations in India, Thailand and Singapore. One India-based consultant criticised the absence of anyone with direct management responsibility on day-to-day matters for the whole of Tata Steel. “I think the company should have done a lot more to try to integrate its [Indian and European operations] rather than the Indian management adopting a largely hands-off approach. There are a lot of people in the company who should be working together but are at cross purposes.” This argument was rejected by Lord Bhattacharyya, Director of the Warwick Management Group at Warwick University in the UK and a confidante of Mr Tata. He says it was right for Tata Steel to keep the identities of its Indian and European operations separate, given a big difference in their size and characteristics. “People do talk to each other from the different parts of the company, so in this sense there is a sufficient amount of integration going on,” he says. “The management of Corus is doing a good job and I think over the longer term the deal will be seen as being a sensible and positive move for Tata.”

Debate also surrounded the way in which Tata handled its acquisition of JLR, with commentators at the time uncertain about the wisdom of the deal as previous owners Ford and BMW had failed. Also, commentators were concerned about the way in which it appeared to be being integrated. Unfortunately for Tata, the deal coincided with the global financial crisis. Petrol prices spiked, bank collapses spooked consumers, credit markets froze and demand for luxury cars was hit hard. JLR sales plunged 32% in 10 months and the division lost €807m in the year. Tata’s debt nearly doubled to €12.9bn, hitting its share price and credit rating. With 16,000 employees at five UK sites, there was alarm that some might close and production be sent overseas. As one banker remarked: “if they carry on operating JLR as it is, it will fail”. Tata pleaded with the British Government for assistance, but support for JLR was refused.

Chairman Ratan Tata was quick to reassure UK employees with a personal visit to JLR. He recalled that his father had bought a classic Jaguar half a century ago and talked about reviving the revered British Daimler brand and returning Jaguar to racing. Six hundred more skilled staff were hired to help develop environmentally friendly cars.

JLR had other challenges. It had relied on Ford Credit to finance its operations and sales and now needed to switch financing to other providers. All its information technology was based on Ford systems and the retained CEO David Smith commented: “the IT is an absolute hydra”.2 To improve efficiencies and save the marques, 2,200 jobs were slashed and tough cuts were made to operation costs.

However, Tata did not insist on tight integration into the group. A three-man strategy board – comprising Ratan Tata, the head of Tata Automotive and David Smith, MD of JLR, was formed – but the JLR executive committee, directly responsible for company operations, had no Tata representatives. Smith commented: “Tata wants us to be autonomous – I’ve got all the executive authority I need … We can make decisions quickly – very different from life at Ford. Relationships with Tata are based on individual relationships.” Ratan Tata also commanded respect. “The designers love him, because he’s an architect and not only quite capable of telling them what he thinks; he can say it in the right language too” (Smith). JLR has also used Tata Motors’ expertise in cost control and Tata Consultancy Division’s skills in information technology.

In 2012, JRL introduced new models including the hot selling Range Rover Evoque – an all-aluminium bodied car originally started by Ford, boasting improved fuel consumption and better performance. A thousand jobs were added in the UK and new manufacturing capacity was built abroad helped by strong demand in India and China. By the end of 2016, JLR was boosting the credit ratings of the entire Tata Motors valuation, as it accounted for 90% of its value. In particular, Jaguar had introduced new models into high-growth entry-level premium segments (Jaguar XE and F-Pace) and JLR as a whole produced record-breaking results selling 583,312 vehicles, up 20% on the previous year and beating the likes of BMW, Mercedes and Audi in the crucial growth markets of China, Europe and the US. The “staying power” of Tata has been amply rewarded.

Sources: Management Today, 1 May 2009; Financial Times, 4 August 2008; The Hindu, 2 September 2012; Financial Times, 7 November 2012; www.nasdaq.com/…/jaguar-land-rover-ended-2016-with-highest-relative-growth-com, 23 January 2017

7-5 Walkman, iPod; Sony, Apple: Decline and Fall?

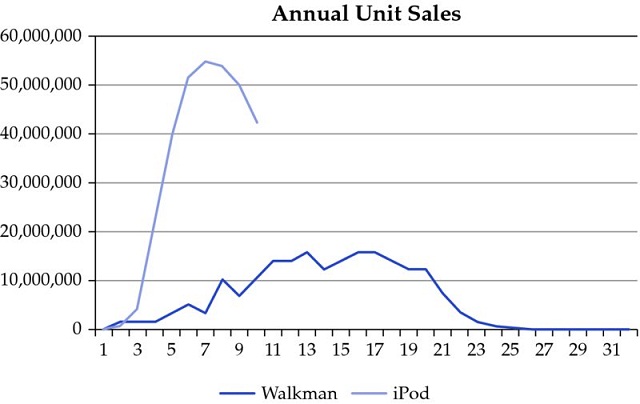

In 2012, a music-loving writer who grew up in the 1980s published a blog wondering if the decline that befell his beloved Sony Walkman would be replicated by that of his newly beloved Apple iPod, and how the fate of the two corporations that produced these products might be linked to their rise and fall.

The blogger admitted that his data was a little sketchy, but he pieced together a chart that looked like this to compare the sales trajectories of the Walkman and the iPod (year 1 for the Walkman is 1979 and year 1 for the iPod is 2002).

The Walkman was so radical in the late 1970s and early 80s that it took a while to catch on. But with the personal fitness craze that got people out of their cars and into the streets and gyms to jog, cycle or walk, the Walkman started to take off.

While the Walkman’s rise was impressive, it is dwarfed by the sales numbers that the iPod put up in its first few years on the market. The iPod is probably the first tangible Apple product of the second Steve Jobs era (Jobs returned to the company in 1997 having been out for 12 years after he was fired in 1985). It helped save Apple, which had struggled to compete in the late 1980s and 90s. However, by 2012 it was looking like the decline in iPod sales would be as sharp as their rise.

Both the Walkman and the iPod define their eras in similar ways, both are icons of their generations, but what the Sony and Apple corporations did in response to their rise and fall was quite different.

As Walkman sales dropped off, Sony followed the waves of change in the portable music industry creating a Discman, which played compact discs and looked like a bigger version of the Walkman, and then an MP3 player with similar styling. But as these proved to be not as successful as the Walkman, Sony moved toward acquiring companies that produced content (e.g. music and movies). They believed that this would be where the money was, rather than in products for delivering that content.

Sony’s approach spread their risk, which was useful, as Apple, with no experience in the portable music industry, would come to quickly overwhelm the portable music market (including Sony’s MP3 players) with the iPod.

Apple, with Jobs back at the helm, and having learned some hard lessons by being out-played by Microsoft and their increasingly ubiquitous operating system in the PC wars of the 1980s and 90s, would seek to springboard on from the success of the iPod in different ways…

Writing your own “corporate advantage” case

Writing your own “corporate advantage” case

Refer to the section “Using Strategy Pathfinder for Assessments and Exams” at the end of the book (see p. 385). Under “The Mini Case” and “The Briefing Note”, guidance is given about how you can create your own case. You may already have an interest in organisations around you that you would like to understand in more depth – and this is a good vehicle for that purpose. There are also a large number of websites that highlight interesting organisations that you might want to find out more about. For instance:

- Websites for national newspapers

- Forbes

- TechCrunch

- uk.businessinsider.com

- www.fastcompany.com

- www.huffingtonpost.com.

It is also worth noting that in the UK there is an excellent website for company information at Companies House. The address is https://beta.companieshouse.gov.uk/.

Information for corporate advantage cases is normally obtained from secondary sources such as those listed above, as it would be difficult to experience the added value of a corporate headquarters unless you are an employee of the organisation. However, by identifying key business units and the organisational structure, plus basic information about headquarter size, you should be able to form an opinion about the way in which the organisation has a corporate advantage. What are the links between the business units? Are synergies being exploited? How is the organisation growing? Can you identify the profitability of the business units and show how group profits and costs are made up? If you want to be ambitious, could you value the business units on a stand-alone basis, by comparing with similar stand-alone businesses and then calculate the expected value of the whole group versus the actual stock market value? Is the stock market fairly valuing the whole organisation?

![]()

Notes

- 1. Armstrong, A. (2017) Unilever to offload Flora and other spreads as it regroups after Kraft Heinz bid, Daily Telegraph, 6 April.

- 2. The seminal work on the emergence of the multidivisional structure was carried out by Alfred Chandler, a business historian, whose ground-breaking book Strategy and Structure, Chapters in the History of American Enterprise (MIT Press), published in 1962, charted the rise of the M-form in the United States, where DuPont, facing a crisis in its businesses that were managed centrally by function, where there was little or no business experience, realised that they should be organised by business division, with the central executive being focused on the strategy of the whole organisation (corporate strategy). This gave rise to the enduring dictum that “structure follows strategy”.

- 3. This may seem a somewhat cynical observation, but the basis of “agency theory” lies in the conflict of (self) interests between the owners of firms (shareholders) and their agents, the managers of firms. In this context, Michael Jensen has noted that owner–agent interests clash when it comes to the payout of “free cash flow” (i.e. “cash flow in excess of that required to fund all projects that have positive net present values when discounted at the relevant cost of capital”). While owners might logically expect such cash to be paid out to them, Jensen suggests that “managers of firms with unused borrowing power and large free cash flows are more likely to undertake low-benefit or even value-destroying mergers” (1986: 328). He strongly advocates high levels of debt as a device to ensure self-discipline on inherently wasteful managers. In a later provocative Harvard Business Review article (1989), Jensen argues that the leveraged buyout (LBO), with its high level of debt, is a business form that, due to its debt-enforced focus on efficiency and shareholder value, threatens the “Eclipse of the Public Corporation” (the title of his article).

- 4. This is an example of a potential “holdup” problem and is normally linked to “relationship-specific assets” (i.e. investments that one party makes that are specific to the needs of another party). It is often impossible to formally specify the nature of the relationship in such a way as to protect the vulnerable party from being exploited once the investment has been made (“incomplete contracting”) and hence integration is often the preferred route. There are many specific texts on the complex arena of transaction cost economics but Besanko, D., Dranove, D., Schaeffer, S. and Shanley, M. (2009) Economics of Strategy, 5th edn, Harvard Business School Press, a general text, offers valuable insights in the context of strategy.

- 5. Rumelt, R. P. (1974) Strategy, Structure and Economic Performance, Harvard Business School Press, describes a major study on the relationship between performance and relatedness. He revisited the study in 1986, coming up with essentially the same findings of higher value from related diversification. While some authors were supportive of Rumelt's main contentions, a significant body of research was in disagreement. Overall, using market-based measures of relatedness has produced equivocal evidence on the link between firm performance and the composition of the corporate business portfolio, with few strong findings on either side and no consensus. For a summary of the situation and a discussion of possible causes for a lack of a relationship, the interested reader could usefully start with Robins, J. and Wiersema, M. F. (1995) A resource-based view of the multibusiness: Empirical analysis of portfolio interrelationships and corporate financial performance, Strategic Management Journal, 16(4): 277–99.

- 6. McKiernan, P. (1992) Strategies of Growth, Routledge, offers a detailed account of the boxes and, in particular, the problems that such classification bring when most businesses fall into the “dog” box, for which the theoretical strategic imperative is “divest”.

- 7. In 1981, there were nine different matrices that managers could choose from, as rival consultancies developed their own frameworks to help beleaguered corporate managers shape their portfolio of business and allocate resources within it (Wind, Y. and Mahajan, V. J. (1981) Designing a product and business portfolio, Harvard Business Review, 59(1): 155).

- 8. Each factor is given a weight for its importance (adding to a total of 1) and this is multiplied by a ranking (1–5) of how well placed the organisation is against others in the industry. For example, if market share (part of competitive position) is deemed to have a weight of 0.3 and the business is well placed as the market leader (5) then the weighted score for market share is 1.5 (0.3 3 5).

- 9. Risk diversification was always difficult to justify as a benefit to shareholders because, as the capital asset pricing model tells us, it is only unsystematic risk that can be diversified away and shareholders can do this themselves. They can also do so with far lower transaction costs than a corporate entity that generally must buy all of a firm at a takeover premium to normal market price, whereas a shareholder can buy a small part of a firm (via shares) at the non-premium market price. Diversifying non-systematic risk at the corporate level is a risk reduction strategy for managers not shareholders.

- 10. The seminal paper by Prahalad, C. K. and Bettis, R. A. (1986) The dominant logic: a new linkage between diversity and performance, Strategic Management Journal, 7(6): 485–501, brought this cognitive perspective into the mainstream of strategy thinking and reminded us of the importance for synergy of how senior managers view the businesses (dominant logic) and the inter-business mechanisms they put in place on the basis of this logic. The authors were responding to the narrowness of traditional product, process, or market measures of diversity/relatedness and stressed instead the importance of the “strategic variety” among the businesses.